De/Constructing DIY Identities in a Trans Music Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cultural Geography of Civic Pride in Nottingham

A Cultural Geography of Civic Pride in Nottingham Thomas Alexander Collins Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of Geography April 2015 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Tom Collins The right of Tom Collins to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii Acknowledgements Thanks to David Bell, Nichola Wood and everyone at the School of Geography. Thanks to the people of Nottingham and all the participants I interviewed. Thanks to my family. Thanks to Kate, Dan, Rachel, Martin, Tom, Sam, Luca, Taylor and to everyone who has heard me witter on about civic pride over the past few years. iv Abstract This thesis examines how people perceive, express, contest and mobilise civic pride in the city of Nottingham. Through interviews, participant observation and secondary resource analysis, I explore what people involved in the civic life of the city are proud of about Nottingham, what they consider the city’s (civic) identity to be and what it means to promote, defend and practice civic pride. Civic pride has been under-examined in geography and needs better theoretical and empirical insight. -

DIY Identities in a DIY Scene: Trans Music in the UK

This is an open access author copy of a chapter published in the edited book: The Emergence of Trans: Cultures, Politics and Everyday Lives. It is an updated version of an essay first published in the journal Sexualities, under the title “De/constructing DIY identities in a trans music scene”. To cite this chapter in formal academic work, please use the published version: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315145815 DIY identities in a DIY scene: trans music events in the UK Kirsty Lohman and Ruth Pearce The past three decades have seen the emergence of an increasingly vigorous and outspoken trans movement in the United Kingdom. Resulting political and social changes have been accompanied by an increasing number of individuals willing to disclose their trans status and be publicly trans. With the development of ‘new modes’ and ‘different codes’ of trans identity and political activism (Whittle, 1998: 393), and an increasingly visible trans population, the stand- alone trans has also come to operate as an organising category for cultural forms. Whereas previous terminologies such as ‘transsexual’, ‘transvestite’ (and perhaps even ‘transgender’) provided more distinct categorical accounts of gender-variant possibility, ‘trans’ is intentionally open and – like ‘queer’ – refuses any clear or coherent definition (Pearce, Steinberg and Moon, 2019). In this chapter, we reflect on what it might mean to ‘do’ trans in a contemporary cultural context, in the tradition of recent accounts of trans music, theatre and performance (see, for instance Halberstam, 2005; Kumpf, 2016; Gossett, Stanley and Burton, 2017; Jaime, 2017; Landry, 2018). While there have always been trans performers, opportunities for their involvement in somewhat regular trans events have historically been limited. -

Nottingham's Vigils for Orlando Notts Lgbt Health Issues

NOTTINGHAM’S VIGILS FR FOR ORLANDO EE “It gets better”, they say - and it does, but the graph of “getting bet- QB terness” is jagged not smooth; there are many places where it falls back and the Orlando tragedy was one Nottinghamshire’s such place. Queer Bulletin Several vigils were held in Nottingham to commemorate the victims and to August/September 2016 remind ourselves that there are al- Number 91 ways those who wish to reverse the progress which has been made. In this issue Events such as these make real that Lions in Nottingham often intangible entity “the LGBT+ Super Victor Community” and show that hope and Amiable vultures love will triumph over hate. Family Pride Smokeless Pride Something for 20s & 30s Kazoos Three free films Worksop awakes And other stuff NOTTS LGBT HEALTH ISSUES The focus group which met in May Addressing high risk taking to discuss LGB health issues with sexual behaviour Nottingham Clinical Commission- Sexuality and gender support ing Group, prioritised the following: Dealing with HIV diagnoses Supporting adherence to medi- If you have any information, news, staff training in LGBT awareness; cations gossip or libel or wish to comment specialist LGBT services; proac- on anything in QB, please contact tive publicity for those services; Patients can self-refer to this coun- greater emphasis on prevention; selling service or be referred by QB early intervention in mental health external agencies. Notts LGBT+ Network issues; concerns for elderly LGBT 7 Mansfield Road If you would like to refer your- people. Nottingham NG1 3FB self for this counselling please call or e-mail Since then, we have been given our contact centre on:- 01159 627 details of a specialist sexual health 627 between 8:30am and 7pm [email protected] counselling service for patients Mon. -

Call It out in Nottingham It's Pride Time in Notts

CALL IT OUT FR IN NOTTINGHAM EE The Call it Out Pride in Football event took place QB at the Nottingham Forest ground over the weekend of June 9th. Many LGBT Nottinghamshire’s football groups were in at- tendance: Spurs, Arsenal, Queer Bulletin Notts Trickies, Celtic, WBA, Brighton Aston Villa July/August 2018 ….. Here’s the Liverpool Number 103 group. One session included a In this issue panel discussion on what it would take for an elite foot- Footballers play cricket baller to come out. This Pride everywhere was set in the context of a The big cheque lengthy article in the Sun Artichokes Lord Longford about a bisexual footballer. Hammer and tongues The Sun proclaims that it Bunions knows the footballer’s Gongs identity, but chooses not to Dine no more reveal it. May 17th Mama Marsha Ryan Atkin, the sport's first New flags ever openly gay referee - Extravaganzas tweeted his anger at the Dancing queens story and at the fact that such high-profile news out- lets still feel it's acceptable And other stuff to imply a threat that they could 'out' the player in question. It's that 'we know who you are' state- ment which is insidious. IT’S PRIDE TIME IN NOTTS If you have any information, news, gossip or libel or wish to comment on anything in QB, please contact QB Notts LGBT+ Network 7 Mansfield Road Nottingham NG1 3FB or e-mail [email protected] The Pride parade will congregate at 11am on Castle Gate, adjacent to The deadline for the next edition Marks and Spencer. -

Improving the Mental Health Outcomes of Nottingham's LGBT Populations

Improving the mental health outcomes of Nottingham’s LGBT populations Quantitative analysis of existing national and regional statistics concerning the mental health needs and healthcare experiences of LGBT people Authors: Tammy Ayres, ReBecca Barnes, Clare GunBy and Katherine Johnson June 2019 This research has been commissioned by NHS Nottingham City Clinical Commissioning Group Table of Contents Page Glossary of Terms 2 Executive summary 3 1. Introduction 6 a. Data sources 6 b. A note on terminology 7 2. Measuring sexual orientation and gender identity: 8 population estimates 3. The characteristics of LGBT populations 12 4. Experiences of discrimination and victimisation related 14 to sexual orientation and/or gender identity 5. LGBT people’s health and wellbeing 16 a. Physical health 17 b. Health risk behaviours 20 c. Mental health and wellbeing 21 6. LGBT people’s experiences of accessing healthcare 24 7. Trans people’s experiences of accessing gender identity 28 services 8. LGBT people’s experiences of accessing mental health 30 services 9. Conclusion 35 References 38 1 Glossary of Terms Asexual A person who does not experience a sexual/romantic attraction to others Umbrella term used to describe a sexual orientation/attraction towards more Bisexual than one gender/sex (bi, pan and queer may also be used) Having a gender identity that aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth Cisgender (non-trans may also be used) A person who has a sexual orientation/attraction to someone of the same Gay sex/gender e.g., a man who has a sexual -

Major LGBT Global Events Updated November 5, 2012

Atlanta, Ga., U.S.A. Bisbee, Ariz., U.S.A. Brooklyn, N.Y., U.S.A. Chicago, Ill., U.S.A. Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.A. Dayton, Ohio, U.S.A. Erie, Pa., U.S.A. Florianopolis, Brazil Guadalajara, Mexico Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A. Kansas City, Mo., U.S.A. Lansing, Mich., U.S.A. Long Island, N.Y., U.S.A. Mexico City, Mexico Monterey, Calif., U.S.A. New Hope, Pa., U.S.A. AMERICAS Joining Hearts Atlanta Bisbee Pride Weekend Brooklyn Pride PRIDEChicago Cincinnati Week of Pride Dayton Pride Erie Pride 2013 Parade Florianopolis Pride Guadalajara Gay Pride Honolulu Gay Pride Kansas City Pride Festival Statewide March Long Island Pride Mexico Pride March Swing for Pride Women’s New Hope Celebrates Albany, N.Y., U.S.A. Jul 20 TBD TBD Jun 28 - 30 Jun 29 TBD & Rally TBD TBD Jun 1 TBD Aug 24 Jun 8 TBD Golf Tournament Pride Capital Pride 2013 TBD TBD TBD May 30 - Jun 9 Atlanta, Ga., U.S.A. Bogota, Colombia Buenos Aires, Argentina Chicago, Ill., U.S.A. Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A. Denver, Colo., U.S.A. Fort Collins, Colo., U.S.A. Guadalajara, Mexico Houston, Texas, U.S.A. Key West, Fla., U.S.A. Las Vegas, Nev., U.S.A. Los Angeles, Calif., U.S.A. Miami, Fla., U.S.A. Atlanta Pride Bogota Gay Pride Buenos Aires Pride Northalsted Market Days Cleveland Pride Denver PrideFest 2013 Eugene, Ore., U.S.A. Fort Collins PrideFest 2013 International LGBT Pride Houston Bone Island Weekend Gay Days Las Vegas Primetime White Party Week Monterrey, Mexico New Orleans, La., U.S.A. -

Pride Festival Buenos Aires, Argentina Texas Freedom Parade TBD TBD July 14 TBD U.S.A

Major LGBT Global Events Updated December 1, 2013 Boston, Mass., U.S.A. Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A. Fire Island, N.Y., U.S.A. Humboldt, Calif., U.S.A. AMERICAS Boston Youth Pride 2014 Cleveland Pride Ascension Fire Island Humboldt Pride Parade Albany, N.Y., U.S.A. TBD Jun 28 TBD and Festival Capital Pride 2014 May 28 – Jun 8 Boston, Mass., U.S.A. Colorado Springs, Colo., Flagstaff, Ariz., U.S.A. TBD Latino Pride 2014 U.S.A. Pride in the Pines Indianapolis, Ind., U.S.A. Albany, N.Y., U.S.A. TBD Colorado Springs TBD Indy Pride Say It Loud! Black and Pride 2014 TBD Latino Gay Pride Boston, Mass., U.S.A. TBD Florianopolis, Brazil TBD Boston Dyke March Florianopolis Pride Indianapolis, Ind., U.S.A. Jun 13 Columbia, S.C., U.S.A. Feb 28 - Mar 5 Indiana Black Gay Pride Albuquerque, N.M., U.S.A. South Carolina Pride TBD Albuquerque Pride Boulder, Colo., U.S.A. Festival Fort Collins, Colo., U.S.A. Jun 31 Boulder PrideFest TBD Fort Collins PrideFest 2014 Jackson, Miss., U.S.A. TBD TBD Jackson Black Pride Allentown, Pa., U.S.A. Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A. TBD Pride in the Park 2014 Butte, Mont., U.S.A. Columbus Gay Pride Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Long Island, NY, U.S.A. Moncton, Canada Oklahoma City, Okla., Provincetown, Mass., San Antonio, Texas, U.S.A. Spencer, Ind., U.S.A. Bucharest, Romania Helsinki, Finland Munich, Germany Siegen, Germany Mumbai, India TBD Montana Pride Jun 20 – 21 U.S.A. -

Annual Report 2014

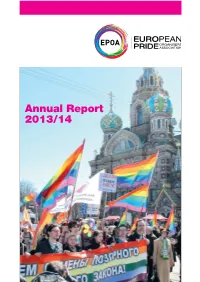

Annual Report 2013/14 EPOA · ANNUAL REPORT 2013/14 Welcome to EPOA! EPOA, the European Pride Organisers Association, had a difficult working year. It is not a secret that maintaining a cross-border non-profit organisation with limited financial means is a daunting task. Add to the mix some new faces and new ideas and fireworks are guaranteed. Unfortunately some of the board members have left us half way through the working year for all sorts of different reasons. But looking back at some of the challenges we came across, it has to be said that the board and its vision has come out even stronger. So with the remaining board members we obviously ensured the proper functioning of the organisation but foremost lined ourselves up towards a better organisa- tion for the future. EPOA, through its members, has an enormous potential for A lot of preparatory work was done towards improving EPOA the future, a reason why we are really actively looking to grow as a whole: search for new members, defining internal proce- this organisation. We are the voice of many LGBTIQ lobby dures, focus on our members’ needs and moving our Euro- groups and that voice should be heard! EuroPride is also a Pride event and its brand to the next level. powerful tool in order towards that same goal. But by bring- ing more members to the table, we will also be able to gener- Talking about EuroPride; we were thrilled with the fantastic ate more energy, more ideas, more support and why not an event our member Oslo Pride put on this year. -

May 2021 Newsletter and RSE Awards Form 2021

Tackling Emerging Threats to Children (TETC) & School Health Hub Newsletter May 2021 Edition Welcome to the May edition of the TETC newsletter. This months newsletter explores Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month, Hate Crime, and Refugee Week. We have provided information and resources to support you in this work. The TETC team continue to be available to all schools via email and telephone to offer guidance, advice and consultations about specific concerns relating to children who are currently attending school and those who are being home educated. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to ask. We would love to hear of any good practice or good news in your settings to share in Lets talk about: future TETC newsletters. Please email [email protected] so we can share positive stories in our future editions. • Child Sexual Exploitation • Radicalization& Extremism • Online Safety and Behavior Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month – June 2021 • Emotional Health & Wellbeing • Gangs, guns and knife crime • Female Genital Mutilation • Gender Identity • Anti-bullying • Prejudice and Hate Crime • Forced Marriage • Honour Based Abuse “Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month (GRTHM) celebrates the diverse ways in • Obesity which Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities add to the vibrancy of life in the UK and • Eating Disorders recognises the varied contributions that these communities have made to British Society historically and today. • Smoking • Alcohol Every June since 2008, people from across the UK have celebrated Gypsy, Roma -

Nottingham City Homes Limited Governing Board Meeting

NOTTINGHAM CITY HOMES LIMITED GOVERNING BOARD MEETING Date: THURSDAY 23 FEBRUARY 2017 Time: 5.30 PM Place: SHEILA ROPER CENTRE, OFF BASLOW DRIVE, LENTON ABBEY, NOTTINGHAM, NG9 2SU Directors of the Board are requested to attend the above meeting on the date and at the time and place stated to transact the following business: George Pashley Company Secretary AGENDA Page Time No. Welcome to the refurbished Sheila Roper Centre from Angie Stanton, Centre Caretaker 5.30 1 INTRODUCTORY ITEMS 1.1 WELCOME 5.40 1.2 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 1.3 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS 1.4 ITEMS FROM THE CHAIR 1.5 MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 26 JANUARY 2017 Attached 3 - 9 5.40 1.6 MATTERS ARISING 2 ITEMS FOR DISCUSSION AND DECISION 2.1 HOUSEMARK CORE BENCHMARKING REPORT 2015/16 Attached 10 - 64 5.40 Presentation from Rachael Collings (Housemark) 3 ITEMS TO NOTE 3.1 QUARTER THREE PERFORMANCE SUMMARY 2016/17 Attached 65 - 69 6.40 Report Of The Performance Manager, Business Transformation 3.2 2016/17 FINANCE REPORT – PERIOD 9 (DECEMBER 2016) Attached 70 - 79 6.55 Report of the Assistant Director of Finance and Procurement 1 3.3 ‘FIXING OUR BROKEN HOUSING MARKET’ THE Attached 80 - 97 7.10 GOVERNMENT’S HOUSING WHITE PAPER, PUBLISHED IN FEBRUARY 2017 Report of the Director of Investment and Business Services 3.4 COMPANY SECRETARY’S REPORT Attached 98 - 106 7.25 Report of the Company Secretary 3.5 FEEDBACK FROM BUILD A BETTER NOTTINGHAM Attached 107- 110 7.35 STEERING GROUP ON 2 FEBRUARY 2017 Report of the Chief Executive 4 CLOSING ITEMS 4.1 ANY OTHER BUSINESS - 4.2 DATE OF NEXT MEETING – 30 MARCH 2017 - 2 ITEM: 1.5 THE BOARD 23 FEBRUARY 2017 NOTTINGHAM CITY HOMES LIMITED THE BOARD MINUTES of the PUBLIC MEETING held on 26 JANUARY 2017 at the St Ann’s Valley Centre, 2 Livingstone Road, St Ann’s, Nottingham, NG3 3GG. -

Explore. Play. Eat. Stay #Lovenotts | Ready to Blow Your Mind? Welcome to Nottingham Home of Robin Hood, Castles, Caves and Culture

VISITNOTTINGHAM & NOTTINGHAMSHIRE 2020 EXPLORE. PLAY. EAT. STAY #LOVENOTTS | www.visit-nottinghamshire.co.uk READY TO BLOW YOUR MIND? WELCOME TO NOTTINGHAM HOME OF ROBIN HOOD, CASTLES, CAVES AND CULTURE Nottingham is the home of Robin Hood and his spirit It’s a city with a sense of fun, and a renowned is more alive here today than ever before. The city is vibrant live music scene. A city of festivals and famous for its castle on the hill, vibrant culture in its carnivals celebrating everything from caves, streets and curious caves beneath your feet. Once comedy, cider and cinema. It’s a city to feel safe in, named the “Queen of the Midlands”, celebrated with Purple Flag status and more Best Bar None for its lace, breweries and rebellious spirit, today accredited venues than any other UK city. it’s an attractive and fun place to visit, brimming It’s a to pick up THE WORLD'S FIRST FREE ROAM VR ARENA RIGHT HERE IN NOTTINGHAM with creative charm and recently named the UK’s fantastic shopping destination treats and souvenirs. High street favourites and friendliest city. major shopping centres sit alongside charming CAN YOU SURVIVE A ZOMBIE APOCALYPSE? FIGHT OFF Nottingham is a city steeped in legend and boutiques and eclectic independent shops. Visit WAVES OF AI ROBOTS IN DEEP SPACE? OR CAN YOU SOLVE A history and is a UNESCO City of Literature. quirky Hockley, the indie Cobden Chambers or the MIND BENDING GRAVITY DEFYING MAZE? It’s a city of rebels, once home to reform rioters, upmarket Exchange arcade. -

A Project of the Human Rights Committee of Interpride Un Proyecto Del Comité De Derechos Humanos De Interpride 2016 | 2017

International Association of Pride Organizers A Project of the Human Rights Committee of InterPride Un proyecto del Comité de Derechos Humanos de InterPride 2016 | 2017 InterPride member | miembro 2016 | 2017 PrideRadar InterPride Inc. – International Association of InterPride Inc., Asociación Internacional de Organizadores Pride Organizers de Eventos del Orgullo Lésbico, Gay, Bisexual, Transgénero Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for orga- e Intersexual – en inglés International Association of nizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Pride the USA and is a 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization under US law. It is Organizers. funded by membership dues, sponsorship, merchandise sales and do- nations from individuals and organizations. Fundada en 1982, InterPride es la asociación de organizadores de even- tos (marchas, protestas y celebraciones) del orgullo LGBTI —conocidos Our Vision también como prides—, más grande del mundo. InterPride esta esta- A world where there is full cultural, social and legal equality for all. blecida en el estado de Texas Estados Unidos bajo el apartado 501(c)(3) como una organización exenta de impuestos de acuerdo a las leyes Our Mission fiscales estadounidenses. InterPride esta financiada por las cuotas de Empowering Pride Organizations Worldwide sus miembros, patrocinios, la venta de artículos, y de donaciones de individuos y organizaciones. We promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride on an inter- national level and encourages diverse communities to hold and attend Nuestra misión Pride Events. InterPride increases networking, communication and edu- La misión de InterPride es promover el movimiento del orgullo LGBTI a cation among Pride Organizations and collaborates with other LGBTI escala internacional y alentar a que se mantengan vigentes y que se and Human Rights organizations.