Towards a Critique of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Rem Koolhaas: an Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Volume 16 - 2008 Lehigh Review 2008 Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16 Recommended Citation Fox, Daniel, "Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation" (2008). Volume 16 - 2008. Paper 8. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lehigh Review at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 16 - 2008 by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation by Daniel Fox 22 he three Master Builders (as author Peter Blake refers to them) – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright – each Drown Hall (1908) had a considerable impact on the architec- In 1918, a severe outbreak ture of the twentieth century. These men of Spanish Influenza caused T Drown Hall to be taken over demonstrated innovation, adherence distinct effect on the human condi- by the army (they had been to principle, and a great respect for tion. It is Koolhaas’ focus on layering using Lehigh’s labs for architecture in their own distinc- programmatic elements that leads research during WWI) and tive ways. Although many other an environment of interaction (with turned into a hospital for Le- architects did indeed make a splash other individuals, the architecture, high students after St. Luke’s during the past one hundred years, and the exterior environment) which became overcrowded. Four the Master Builders not only had a transcends the eclectic creations students died while battling great impact on the architecture of of a man who seems to have been the century but also on the archi- influenced by each of the Master the flu in Drown. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Tobias Armborst – the Dream of a Lifestyle: Marketing Master Planned Communities in America • Kenny Cupers – Cities in Search of the User

program 1 Thursday November 11 2010 De Nieuwe Bibliotheek Almere (Public Library of Almere) Stadhuisplein 101, 1315 XC Almere, the Netherlands 09h00 doors open, registration & coffee 09h30 introduction by Michelle Provoost, director INTI opening by René Peeters, alderman City of Almere 10h15 theme 1: Participation and Community Power moderator Michelle Provoost • Tobias Armborst – The Dream of a Lifestyle: Marketing Master Planned Communities in America • Kenny Cupers – Cities in search of the user 11h45 theme 2: The Architect and the Process • Kieran Long (Evening Standard) interviews Kees Christiaanse (KCAP) and Nathalie de Vries (MVRDV) on the role of the Architect in the development of New Towns in Russia and Asia 13h00 lunch at Centre for Architecture CASLa, Weerwaterplein 3, 1324 EE Almere 14h30 theme 3: New Towns as Political Instrument moderator: Wouter Vanstiphout • Zvi Efrat – About Politics and Architecture of New Towns in Israel • Azadeh Mashayekhi – Revisiting Iranian New Towns • Dan Handel – Grid and Revelation: Cities of Zion in the American West • Vincent Lacovara – Specific Flexibility in Place-making - or - The Law of Unforseen Planning 17h00 drinks and dinner at restaurant Waterfront Esplanade 10, 1315 TA Almere (Schouwburg of Almere) 2 Friday 12 November 2010 Schouwburg of Almere (Theatre of Almere) Esplanade 10, 1315 TA Almere, the Netherlands 09h00 doors open, registration & coffee 09h30 Introduction by Michelle Provoost, director INTI 09h40 theme 4: Left and Right in Urban Planning moderator Felix Rottenberg • Adri -

New Trends En El Mundo

1 NEW TRENDS EN EL MUNDO La cuarta edición del New Trends of Architecture comenzó en Patras, Grecia, Capital europea de la Cultura 2006, en Junio de ese mismo año. La inauguración fue el día 2 de Junio del 2006. New Trends of Architecture fue fundada en el 2001 por un grupo de consejeros japoneses de la cultura y los medios de comunicación, de quince estados miembros de la Unión Europea, Instituciones Culturales europeas y de la Delegación de la Comisión Europea en Japón. El objetivo es crear una plataforma que constituya una oportunidad para compartir ideas y experiencias entre Europa y Asia Pacífico, a través de exposiciones anuales y simposiums para arquitectos emergentes europeos, japoneses y de otros países del Pacífico que tendrán lugar en Japón y otras capitales europeas. El proyecto fue reconocido no solo por el mundo de la arquitectura sino también por el mundo diplomático. El antiguo director de la comisión europea, Romano Prodi y, el primer ministro de Japón, Junichiro Koizumi, mencionaron este proyecto especialmente como un programa de intercambio importante durante la cumbre euro japonesa en Julio 2002. En el año 2004, coincidiendo con la ampliación de la Unión Europea, la tercera edición de New Trends of Architecture fue presentada como una nueva iniciativa: un proyecto para las regiones de Europa y el Pacífico asiático. La exposición, acompañada de un simposium, fue organizada en Lille, Hong-Kong, Tokio, Cork, Melbourne y Anyang. En cada ciudad resultó ser una fuente de encuentros e intercambios enriquecedores. El concepto básico de este proyecto fue inspirado por la idea europea de la Capital Europea de la Cultura. -

Jaarverslag 2012

Jaarverslag 2012 1 Inhoudsopgave Bericht van de ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Raad van Toezicht ................................................................................................................................ 4 Voorwoord ............................................................................................................................................ 5 1 Codarts Rotterdam ...................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Missie...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Opleidingen ............................................................................................................................ 8 1.3 Kengetallen ........................................................................................................................... 10 2 Studenten .................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1 Kroonjuwelen ....................................................................................................................... 12 2.2 Uitvoeringen door Codarts-studenten ................................................................................... 13 2.3 Kengetallen student en onderwijs ........................................................................................ -

Grace La Is Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Principal of LA DALLMAN Architects

Grace La is Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Principal of LA DALLMAN Architects. La’s work is internationally recognized for the integration of architecture, engineering and landscape. Cofounded with James Dallman, LA DALLMAN is engaged in catalytic projects of diverse scale and type. Noted for works that expand the architect's agency in the civic recalibration of infrastructure, public space and challenging sites, LA DALLMAN was named as an Emerging Voice by the Architectural League of New York in 2010 and received the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence Silver Medal in 2007. In 2011, LA DALLMAN was the first practice in the United States to receive the Rice Design Alliance Prize, an international award recognizing exceptionally gifted architects in the early phase of their career. LA DALLMAN has also been awarded numerous professional honors, including architecture and engineering awards, as well as prizes in international design competitions. LA DALLMAN’s built work includes the Kilbourn Tower, the Miller Brewing Meeting Center (original building by Ulrich Franzen), the University of Wisconsin‐Milwaukee (UWM) Hillel Student Center, the Ravine House, the Gradient House and the Great Lakes Future and City of Freshwater permanent science exhibits at Discovery World. The Crossroads Project transforms infrastructure for public use, including a 700‐foot‐long Marsupial Bridge, a bus shelter and a media garden. LA DALLMAN is currently commissioned to design additions to the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts (original building by Harry Weese and landscape by Dan Kiley), the 2013 Master Plan for the Menomonee Valley and the Harmony Project, a 100,000‐square‐foot hybrid arts building for professional dance, which includes a ballet school, a university dance program and a medical clinic. -

OMA at Moma : Rem Koolhaas and the Place of Public Architecture

O.M.A. at MoMA : Rem Koolhaas and the place of public architecture : November 3, 1994-January 31, 1995, the Museum of Modern Art, New York Author Koolhaas, Rem Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/440 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THRESHOLDS IN CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE O.M.A.at MoMA REMKOOLHAAS ANDTHE PLACEOF PUBLICARCHITECTURE NOVEMBER3, 1994- JANUARY31, 1995 THEMUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK THIS EXHIBITION IS MADE POSSIBLE BY GRANTS FROM THE NETHERLANDS MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, LILY AUCHINCLOSS, MRS. ARNOLD L. VAN AMERINGEN, THE GRAHAM FOUNDATION FOR ADVANCED STUDIES IN THE FINE ARTS, EURALILLE, THE CONTEMPORARY ARTS COUNCIL OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, AND KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES. REM KOOLHAASAND THE PLACEOF PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE ¥ -iofiA I. The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (O.M.A.), presence is a source of exhilaration; the density it founded by Rem Koolhaas with Elia and Zoe engenders, a potential to be exploited. In his Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp, has for two "retroactive manifesto" for Manhattan, Delirious decades pursued a vision energized by the relation New York, Koolhaas writes: "Through the simulta ship between architecture and the contemporary neous explosion of human density and an invasion city. In addition to the ambitious program implicit in of new technologies, Manhattan became, from the studio's formation, there was and is a distinct 1850, a mythical laboratory for the invention and mission in O.M.A./Koolhaas's advocacy of the city testing of a revolutionary lifestyle: the Culture of as a legitimate and positive expression of contem Congestion." porary culture. -

WARCHITECTURE Hinted at the Day Before

IIAS_NL#39 09-12-2005 17:03 Pagina 20 > Rem Koolhaas IIAS annual lecture SKYSCRAPERS AND SLEDGEHAMMERS The 10th IIAS annual lecture was delivered in Amsterdam on 17 November by world-famous Dutch architect and Harvard professor ...THE DAY AFTER Rem Koolhaas. Co-founder and partner of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and initiator of AMO, its think-tank/mirror Zheng Shiling from Shanghai, Xing Ruan from Sydney and Anne- image, Koolhaas’ projects include de Kunsthal in Rotterdam, Guggenheim Las Vegas, a Prada boutique in Soho, Casa da Musica in Marie Broudehoux from Quebec City were Koolhaas’ discussants Porto and most spectacularly, the new CCTV headquarters in Beijing. His writings range from his Delirious New York, a retroactive following the lecture. To give our guests a chance to meet their manifesto (1978) to his massive 1,500 page S,M,L,XL (1995), several projects supervised at Harvard including Great Leap Forward Dutch and Flemish brothers in arms, IIAS organized a meeting (2002) and Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (2002) to his most recent volume between a book and a magazine, Content at the Netherlands Architectural Institute in Rotterdam the fol- (2005). On these pages of the IIAS newsletter, itself a strange animal between an academic journal and newspaper, we explore why lowing day. Bearing the title (Per)forming Culture; Architecture and Koolhaas in his last book invites us to Go East; why he has a long-time fascination with the Asian city; why the Metabolists have Life in the Chinese Megalopolis, specialists of contemporary Chi- always intrigued him; why OMA has developed an interest in preserving ancient Beijing; and, perhaps most importantly, why he nese urban change – including scholars of architectural theory, thinks architecture is so closely connected to ideology. -

Exhibitions, Street Art, Galleries and Sculptures

October 2019 – January 2020 exhibitions, street art, galleries and sculptures boijmans.nl/transit 1 Transit Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s long- term renovation has started. During this Transit period, institutions and museums across Rotterdam will be holding exhibitions with works of art from the museum collection under the title ‘Boijmans Next Door’. The Above: After seven months of collection will also be travelling to some of relocating the permanent the world’s top museums. In the meantime, collection, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen is empty. construction of the Depot continues apace photo: Aad Hoogendoorn and this landmark is set to open in 2021. Right: Artist impression of the exterior of the Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen. Design: MVRDV Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen It is the first depot in the world that provides access to a complete collection without the intervention of a curator. The 40-metre high, mirrored building is a design from the Rotterdam architect Winy Maas from MVRDV and offers a beautiful, panoramic view of the city and the port from the freely accessible roof garden with restaurant. kunsthal.nl 2 Kunsthal Rotterdam Museumpark The Kunsthal Rotterdam is housed in Westzeedijk 341 a striking building designed by OMA/ Rem Koolhaas (1992). The Kunsthal presents several exhibitions simultaneously, taking visitors on a journey through various cultures and art movements from modern masters and contemporary art to forgotten cultures, photography, fashion and innovative design. Joana Vasconcelos. ‘I’m Your Mirror’ This impressive retrospective features the work of the famous Portuguese artist Joana Vasconcelos (1971). ‘I’m Your Mirror’ shows sculptures and installations such as ‘Lilicoptère, 2012’, a gold-plated helicopter Above: Lilicoptère, 2012 decorated with Swarovski crystals and pink © Joana Vasconcelos, FMGB Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa. -

First Generation Second Generation

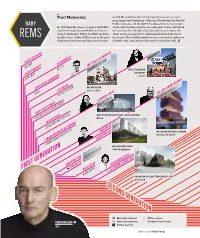

by Paul Makovsky world. Not only has the firm designed some of our era’s most important buildings—Maison à Bordeaux, the Seattle BABY Public Library, and the CCTV headquarters, to name just In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia a few—but its famous hothouse atmosphere has cultivated and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon VriesenVriesen-- the talents of hundreds of gifted architects. Look at the dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan chart on these pages: it is a distinguished architectural REMS Architecture. Today OMA is one of the most fraternity. These OMA grads have now created an influence influential architectural practices in the all their own, and they are the ones to watch in 2011. P ZAHA HADID RIENTS DIJKSTRA EDZO BINDELS MAXWAN MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH WEST 8 SAUERBRUCH HUTTON EVELYN GRACE ACADEMY CHRISTIAN RAPP London RAPP + RAPP CHRISTOPHE CORNUBERT M9 MUSEUM LUC REUSE Venice, Italy WILLEM JAN NEUTELINGS PUSH EVR ARCHITECTEN NEUTELINGS RIEDIJK LAURINDA SPEAR ARQUITECTONICA KEES CHRISTIAANSE SOUTH DADE CULTURAL ARTS CENTER KGAP ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS Miami YUSHI UEHARA ZERODEGREE ARCHITECTURE MVRDV WINY MAAS MUSEUM AAN DE STROOM Antwerp, Belgium RUURD ROORDA KLAAS KINGMA JACOB VAN RIJS KINGMA ROORDA ARCHITECTEN BALANCING BARN Suffolk, England FOA WW ARCHITECTURE SARAH WHITING FARSHID MOUSSAVI RON WITTE FIRST GENERATION MIKE GUYER ALEJANDRO ZAERA POLO GIGON GUYER MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Cleveland SECOND GENERATION Married/partnered Office closed REM KOOLHAAS P Divorced/separated P Pritzker Prize laureate OMA Former partner Illustration by Nikki Chung REM_Baby REMS_01_11_rev.indd 1 12/16/10 7:27:54 AM BABY REMS by Paul Makovsky In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesen- dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. -

A Los Dos Lados Del Espejo a Los Dos

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE MADRID. ETS DE ARQUITECTURA DE MADRID DEPARTAMENTO DE IDEACIÓN GRÁFICA ARQUITECTÓNICA REM A LOS DOS LADOS DEL ESPEJO (REM AT BOTH SIDES OF THE MIRROR) TESIS DOCTORAL, 2015 AUTORA: Belén María Butragueño Díaz-Guerra, Arquitecta DIRECTOR: Javier Francisco Raposo Grau, Doctor Arquitecto ABSTRACT “Our old ideas about space have exploded. In their place comes a surprising range of domains that will define our future.” Rem Koolhaas Fotografía de Rem Koolhaas en la Casa da Música de Oporto (© Rem Koolhaas) 14 15 When talking about Rem Koolhaas, the mirror does not -,*7 0#L*#!2 -,# 32 ,3+#0-31 '+%#1S '2 '1 ,-2&',% 32 polyhedral prism. His mirror gives us the image of Rem the media celebrity, the intellectual, the conceptualizer, the builder, the analyst, the journalist, the actor... This research sets the spotlight on Rem the COMMUNICATOR. "Rem on both sides of the mirror" belongs to a research -, 0!&'2#!230* +#"'Q '21 ',L*3#,!# -, 2&# 0!&'2#!230* production and vice versa. It is aimed at getting to discern whether communication and architectural production collide and converge in the case of great communicators such as Rem Koolhaas, and whether the message and transmission media acquire the same features. -!31',% -, 2&# L'%30# -$ #+ --*&1Q 2&'1 2'1 addresses the evolution of his communicative facet and 2&# 13!!#11'4# 20,1$-0+2'-,1 ', 2&# L'#*" -$ 0!&'2#!230* communication, parallel to the conceptual evolution he underwent throughout his career. Therefore, this research is not so much focused on his theoretical component or on the OMA’s architectural practice, but on the exhibition of his production to the world, especially through his essays and books.