Investigating Vocabulary in Academic Spoken English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spoken BNC2014: Designing and Building a Spoken Corpus Of

The Spoken BNC2014 Designing and building a spoken corpus of everyday conversations Robbie Love i, Claire Dembry ii, Andrew Hardie i, Vaclav Brezina i and Tony McEnery i i Lancaster University / ii Cambridge University Press This paper introduces the Spoken British National Corpus 2014, an 11.5-million-word corpus of orthographically transcribed conversations among L1 speakers of British English from across the UK, recorded in the years 2012–2016. After showing that a survey of the recent history of corpora of spo- ken British English justifies the compilation of this new corpus, we describe the main stages of the Spoken BNC2014’s creation: design, data and metadata collection, transcription, XML encoding, and annotation. In doing so we aim to (i) encourage users of the corpus to approach the data with sensitivity to the many methodological issues we identified and attempted to overcome while com- piling the Spoken BNC2014, and (ii) inform (future) compilers of spoken corpora of the innovations we implemented to attempt to make the construction of cor- pora representing spontaneous speech in informal contexts more tractable, both logistically and practically, than in the past. Keywords: Spoken BNC2014, transcription, corpus construction, spoken corpora 1. Introduction The ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science (CASS) 1 at Lancaster University and Cambridge University Press have compiled a new, publicly- accessible corpus of present-day spoken British English, gathered in informal con- texts, known as the Spoken British National Corpus 2014 (Spoken BNC2014). This 1. The research presented in this paper was supported by the ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science, ESRC grant reference ES/K002155/1. -

E-Language: Communication in the Digital Age Dawn Knight1, Newcastle University

e-Language: Communication in the Digital Age Dawn Knight1, Newcastle University 1. Introduction Digital communication in the age of ‘web 2.0’ (that is the second generation of in the internet: an internet focused driven by user-generated content and the growth of social media) is becoming ever-increasingly embedded into our daily lives. It is impacting on the ways in which we work, socialise, communicate and live. Defining, characterising and understanding the ways in which discourse is used to scaffold our existence in this digital world is, therefore, emerged as an area of research that is a priority for applied linguists (amongst others). Corpus linguists are ideally situated to contribute to this work as they have the appropriate expertise to construct, analyse and characterise patterns of language use in large- scale bodies of such digital discourse (labelled ‘e-language’ here - also known as Computer Mediated Communication, CMC: see Walther, 1996; Herring, 1999 and Thurlow et al., 2004, and ‘netspeak’, Crystal, 2003: 17). Typically, forms of e-language are technically asynchronous insofar as each of them is ‘stored at the addressee’s site until they can be ‘read’ by the recipient (Herring 2007: 13). They do not require recipients to be present/ready to ‘receive’ the message at the same time that it is sent, as spoken discourse typically does (see Condon and Cech, 1996; Ko, 1996 and Herring, 2007). However, with the increasing ubiquity of digital communication in daily life, the delivery and reception of digital messages is arguably becoming increasingly synchronous. Mobile apps, such as Facebook, WhatsApp and I-Message (the Apple messaging system), for example, have provisions for allowing users to see when messages are being written, as well as when they are received and read by the. -

Marketing-Strategy-Ferrel-Hartline.Pdf

Copyright 2013 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. Marketing Strategy Copyright 2013 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. This is an electronic version of the print textbook. Due to electronic rights restrictions, some third party content may be suppressed. Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. The publisher reserves the right to remove content from this title at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. For valuable information on pricing, previous editions, changes to current editions, and alternate formats, please visit www.cengage.com/highered to search by ISBN#, author, title, or keyword for materials in your areas of interest. Copyright 2013 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). -

SELECTING and CREATING a WORD LIST for ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING by Deny A

Teaching English with Technology, 17(1), 60-72, http://www.tewtjournal.org 60 SELECTING AND CREATING A WORD LIST FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING by Deny A. Kwary and Jurianto Universitas Airlangga Dharmawangsa Dalam Selatan, Surabaya 60286, Indonesia d.a.kwary @ unair.ac.id / [email protected] Abstract Since the introduction of the General Service List (GSL) in 1953, a number of studies have confirmed the significant role of a word list, particularly GSL, in helping ESL students learn English. Given the recent development in technology, several researchers have created word lists, each of them claims to provide a better coverage of a text and a significant role in helping students learn English. This article aims at analyzing the claims made by the existing word lists and proposing a method for selecting words and a creating a word list. The result of this study shows that there are differences in the coverage of the word lists due to the difference in the corpora and the source text analysed. This article also suggests that we should create our own word list, which is both personalized and comprehensive. This means that the word list is not just a list of words. The word list needs to be accompanied with the senses and the patterns of the words, in order to really help ESL students learn English. Keywords: English; GSL; NGSL; vocabulary; word list 1. Introduction A word list has been noted as an essential resource for language teaching, especially for second language teaching. The main purpose for the creation of a word list is to determine the words that the learners need to know, in order to provide more focused learning materials. -

FERSIWN GYMRAEG ISOD the National Corpus of Contemporary

FERSIWN GYMRAEG ISOD The National Corpus of Contemporary Welsh Project Report, October 2020 Authors: Dawn Knight1, Steve Morris2, Tess Fitzpatrick2, Paul Rayson3, Irena Spasić and Enlli Môn Thomas4. 1. Introduction 1.1. Purpose of this report This report provides an overview of the CorCenCC project and the online corpus resource that was developed as a result of work on the project. The report lays out the theoretical underpinnings of the research, demonstrating how the project has built on and extended this theory. We also raise and discuss some of the key operational questions that arose during the course of the project, outlining the ways in which they were answered, the impact of these decisions on the resource that has been produced and the longer-term contribution they will make to practices in corpus-building. Finally, we discuss some of the applications and the utility of the work, outlining the impact that CorCenCC is set to have on a range of different individuals and user groups. 1.2. Licence The CorCenCC corpus and associated software tools are licensed under Creative Commons CC-BY-SA v4 and thus are freely available for use by professional communities and individuals with an interest in language. Bespoke applications and instructions are provided for each tool (for links to all tools, refer to section 10 of this report). When reporting information derived by using the CorCenCC corpus data and/or tools, CorCenCC should be appropriately acknowledged (see 1.3). § To access the corpus visit: www.corcencc.org/explore § To access the GitHub site: https://github.com/CorCenCC o GitHub is a cloud-based service that enables developers to store, share and manage their code and datasets. -

Kayak to Klemtu

Presents KAYAK TO KLEMTU A film by Zoe Hopkins Running time: 90 minutes, Canada, 2018 Languages: English, some Hailhzaqvla Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Twitter: @starpr2 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia Kayak to Klemtu Logline 14-year-old Ella is determined to kayak the length of the inside passage to protest an oil pipeline and honour her late uncle’s legacy. Kayak to Klemtu Short Synopsis 14-year-old Ella is determined to travel the length of the Inside Passage by kayak in order to protect her home. She plans to protest a proposed pipeline that would have oil tanker traffic spoil her beloved homeland’s waters. Ella is prepared to handle all of the challenges put in front of by her this adventure, but most of all the challenge of her whacky family. Her neurotic aunt, her cranky uncle, her wayward cousin, and the memory of her late uncle all tag along for the ride, throwing Ella for a loop. From Tla'Amin to Klemtu, British Colombia, this family navigates their blend of cultures and ideals, while their spirits honour the coast as a place for not just Ella, but everyone, to call home. Kayak to Klemtu One Page Synopsis 14-year-old Ella’s Uncle Bear has passed away. It was his dying wish to have Ella testify against the proposed oil pipeline that is going to ruin their home waters. -

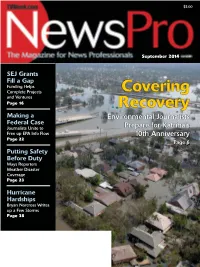

Covering Recovery: 10 Years After Katrina

$5.00 September 2014 SEJ Grants Fill a Gap Funding Helps Complete Projects Covering and Ventures Page 16 Recovery Making a Environmental Journalists Federal Case Journalists Unite to Prepare for Katrina’s Free up EPA Info Flow 10th Anniversary Page 22 Page 6 Putting Safety Before Duty Ways Reporters Weather Disaster Coverage Page 23 Hurricane Hardships Bryan Norcross Writes up a Few Storms Page 38 FROM THE EDITOR Staying Safe, Staying Strong As the Society of Environmental Journalists gathers in New Orleans for its 2014 conference themed “Risk and Resilience,” attendees — occasional Bourbon Street reveling aside — will be hard-pressed not to constantly think about the ravages wrought on the region over the past CONTENTS decade by Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. A DECADE DOWN THE ROAD .............. 6 As the 10th anniversary of Katrina approaches in the summer of 2015, reporters and editors A Guide to Covering Katrina’s will be looking for ways to tell compelling stories in remembrance of the catastrophe. Intended 10th Anniversary as a tool to help generate those story ideas, our cover piece explores the recommendations of NEW ORLEANS ACCENT ................... 12 the experts who dealt with the storm’s aftermath, and yields an assortment of tactics that can SEJ Gathers in a City of Risk and Resilience be taken to create thoughtful, pertinent coverage. Disaster reporting in itself is fraught with risk, and personal safety is ever central to the way MAKING ENDS MEET ........................ 16 reporters do their jobs. Whether it be hurricane, earthquake, wild re, ood, tornado or toxic Fund for Environmental Journalism Fills a Need chemical spill, it’s up to each individual to ensure they are prepared for the hazards they might encounter, as our story on page 23 concludes. -

The National Corpus of Contemporary Welsh 1. Introduction

The National Corpus of Contemporary Welsh Project Report, October 2020 1. Introduction 1.1. Purpose of this report This report provides an overview of the CorCenCC project and the online corpus resource that was developed as a result of work on the project. The report lays out the theoretical underpinnings of the research, demonstrating how the project has built on and extended this theory. We also raise and discuss some of the key operational questions that arose during the course of the project, outlining the ways in which they were answered, the impact of these decisions on the resource that has been produced and the longer-term contribution they will make to practices in corpus-building. Finally, we discuss some of the applications and the utility of the work, outlining the impact that CorCenCC is set to have on a range of different individuals and user groups. 1.2. Licence The CorCenCC corpus and associated software tools are licensed under Creative Commons CC-BY-SA v4 and thus are freely available for use by professional communities and individuals with an interest in language. Bespoke applications and instructions are provided for each tool (for links to all tools, refer to section 10 of this report). When reporting information derived by using the CorCenCC corpus data and/or tools, CorCenCC should be appropriately acknowledged (see 1.3). § To access the corpus visit: www.corcencc.org/explore § To access the GitHub site: https://github.com/CorCenCC o GitHub is a cloud-based service that enables developers to store, share and manage their code and datasets. -

Court Record

Court Record Regarding the Trials of Mills v. MacMillan III and Another, Firefighters v. Sunman, and Wiki Team v. Sunman Edited and Annotated by Cat (@CatStlats) Legend: Prosecution – red PP Defense – blue DD Court – green CC Witness – purple WW Bot – black BB ?? Some people played multiple roles throughout the proceedings. Each message is marked according to the role played at that time. Disclaimer: Wow, this is a lot of words. Hopefully, I’ve edited it down enough and marked all the important parts, and I 100% messed something up somewhere, so if you notice anything, let me know! Direct any questions or comments to @CatStlats on Twitter or @Cat#1616 on Discord. ============================================================== Guild: BLASEBALL (on Siesta) Channel: THE COURTROOM OF THE HONORABLE JUDGE SINS / the-courtroom Topic: Hellmouth Courthouse. A Fair™️ courtroom. ============================================================== Opening Notes CC [09-Nov-20 12:05 PM] bailiff_launchpad (he/him) In the Highest Court - Capitalism & Incineration Courts of The Hellmouth Business List (ChD) Outback Steakhouse, West Wing, Trombone Annex, Court 1 Before THE RIGHT HONORABLE JUSTICE JUDGE_KEEPER_SINS Monday 09 November 2020 At 02:00 PM, PST Hybrid Hearing HM-2020-TCIDAJ WMBI Mills v. MacMillan III and another HM-2020-081833 WAFD Firefighters v. Dr. Mr. U. P. Q. Sunman, Ph.D, JD, esq. HM-2020-003235 BWAT Wiki Team v. Dr. Mr. U. P. Q. Sunman, Ph.D, JD, esq. For preparatory purposes, please find here the initial paperwork issued in each of this hearing's -

Film Overview Microplastic Madness

A Cafeteria Culture production Directed and Produced by Atsuko Quirk and Debby Lee Cohen Film Overview Microplastic Madness - Run time: 76 minutes Microplastic Madness is an optimistic take on the local and global plastic pollution crisis as told through a refreshing urban youth point of view with an inspiring take action message. Fifth graders from PS 15 in Red Hook, Brooklyn - a community on the frontline of Climate Change - spent 2 years investigating plastic pollution. Taking on the roles of citizen scientists, community leaders, and advocates, these 10-11 year olds collect local data, lead community outreach, and use their impressive data to inform policy, testifying and rallying at City Hall. They take the deep dive into the root causes of plastic pollution, bridging the connection between plastic, climate change, and environmental justice before turning their focus back to school. There they take action to rid their cafeteria of all single-use plastic, driving forward city-wide action and a scalable, youth-led plastic-free movement. With stop-motion animation, heartfelt kid commentary, and interviews of experts and renowned scientists who are engaged in the most cutting edge research on the harmful effects of microplastics, this alarming, yet charming narrative, conveys an urgent message in user-friendly terms with a take action message to spark youth-led plastic free action in schools everywhere. The film has been accepted to 13 film festivals and received an award. Link to Trailer 16:9 aspect ratio 70 seconds https://vimeo.com/361115158 Director’s Biography Atsuko Quirk - Producer/Director, D.P. and Editor of Microplastic Madness Atsuko is a documentary filmmaker, environmental advocate, and a 21st generation Samurai family member from northern Japan, living in New York City. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Amy | ‘Tis the Season | Meru | the Wolfpack | the Jinx | Big Men | Caring for Mom & Dad | Walt Disney | the Breach | GTFO Scene & He D

November-December 2015 VOL. 30 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES NO. 6 IN THIS ISSUE Amy | ‘Tis the Season | Meru | The Wolfpack | The Jinx | Big Men | Caring for Mom & Dad | Walt Disney | The Breach | GTFO scene & he d BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Le n more about Bak & Taylor’s Scene & He d team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review Amy HHH 2011, she died of alcohol toxicity at the age of Lionsgate, 128 min., R, 27. Drawing on early home movies, newsreel DVD: $19.98, Blu-ray: footage, and recorded audio interviews, Amy $24.99, Dec. 1 serves up a sorrowful portrait of an artist’s Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman This disturbing, dis- deadly downward spiral. Extras include au- concerting, booze ‘n’ dio commentary by the director, previously Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood drugs documentary unseen performances by Winehouse, and Copy Editor: Kathleen L. Florio about British song- deleted scenes.