The Basics of Bloomery Smelting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schoolcraft Blast Furnace

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Schoolcraft National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Blast Furnace Schoolcraft furnace With surveyor William Burt’s discovery of iron ore near Teal Lake in Marquette County in 1844, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula suddenly became a hub of activity. The discovery led to construction of a vast mining and manufacturing industry using forges and blast furnaces. When the Civil War ended, many of the South’s furnaces had been destroyed by the war. Westward expansion was occurring across the plains and demand for iron boomed. It was during this era that many of the Upper Peninsula’s furnaces were constructed. There were advantages to smelting iron ore from charcoal fires. Iron produced in this manner was low in carbon content, making it highly fusable, strong, malleable and able to withstand shocks without cracking. The iron made fine wagon rims, horseshoes, and railroad wheels. Before the boom times were over, 29 separate furnaces were located on the Old Munising, ca. 1870 peninsula, though not all operated simultaneously. The business of iron making required more capital than was readily available in the area and financing and management of the operations was often complex. The first group of investors were from Philadelphia. They wished to develop a resort village on Munising Bay’s east shoreline in 1850. Some 87,000 acres of timber were purchased for $.85 an acre. A village was platted on the east shore of Munising Bay, lots were sold, and a dock was built. Henry Mather and Peter White acted as agents for the group of investors who created the Schoolcraft Iron Company in 1866. -

Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel

ACADEMIC PULSE Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel teelmakers have traditionally viewed Research Continues to Improve the electric arc furnaces (EAFs) as unsuitable Quality of Steel for producing steel with the highest- Even with continued improvements to the Squality surface finish because the process design of steelmaking processes, the steelmaking uses recycled steel instead of fresh iron. With over research community has focused their attention 100 years of processing improvements, however, on the fundamental materials used in steelmaking EAFs have become an efficient and reliable in order to improve the quality of steel. In my lab steelmaking alternative to integrated steelmaking. In at Carnegie Mellon University, we have several fact, steel produced in a modern-day EAF is often research projects that deal with controlling the DR. P. BILLCHRIS MAYER PISTORIUS indistinguishable from what is produced with the impurity concentration and chemical quality of POSCOManaging Professor Editorof Materials integrated blast-furnace/oxygen-steelmaking route. steel produced in EAFs. Science412-306-4350 and Engineering [email protected] Mellon University Improvements in design, coupled with research For example, we recently used mathematical developments in metallurgy, mean high-quality steel modeling to explore ways to control produced quickly and energy-efficiently. phosphorus. Careful regulation of temperature, slag and stirring are needed to produce low- Not Your (Great-) Grandparent’s EAF phosphorus steel. We analyzed data from Especially since the mid-1990s, there have been operating furnaces and found that, in many significant improvements in the design of EAFs, cases, the phosphorus removal reaction could which allow for better-functioning burners and a proceed further. -

5. Sirhowy Ironworks

Great Archaeological Sites in Blaenau Gwent 5. SIRHOWY IRONWORKS There were a number of ironworks in the area now covered by Blaenau Gwent County Borough, which provided all the raw materials they needed – iron ore, limestone and fuel, charcoal at first but later coal to make coke. The Sirhowy ironworks (SO14301010) are the only one where there is still something to see. The works were opened in 1778 with one blast furnace. Although it was originally blown by water power, in 1799 the owners invested in a Boulton and Watt steam engine. This gave them enough power to blow a second furnace, which started production in 1802. In the early years of the 19th century, the pig iron produced at Sirhowy was sent to the Tredegar works a little further down the valley where it was refined, until 1818 when the Sirhowy works were sold and started to send its pig iron to Ebbw Vale. A third furnace was added in 1826 and a fourth in 1839. But by the 1870s iron smelting at Sirhowy was no longer profitable, and the works finally closed in 1882. Like all ironworks in South Wales, the furnaces were built against a steep bank which enabled the ironworkers to load the charge of iron ore, limestone and coke or charcoal fuel more easily at the top of the furnace. All that is now left now are the remains of a bank of blast furnaces with the arches that would originally have linked them to the casting houses in front, and the building that originally housed the waterwheel. -

Studying and Improving Blast Furnace Cast Iron Quality

Т. К. BALGABEKOV, D. K. ISSIN, B. M. KIMANOV, A. Z. ISSAGULOV, ISSN 0543-5846 ZH. D. ZHOLDUBAYEVA, А. Z. AKASHEV, B. D. ISSIN METABK 53(4) 556-558 (2014) UDC – UDK 669.162.2:669.1:669.13=111 STUDYING AND IMPROVING BLAST FURNACE CAST IRON QUALITY Received – Prispjelo: 2013-11-09 Accepted – Prihvaćeno: 2014-04-30 Preliminary Note – Prethodno priopćenje In the article there are presented the results of studies to improve the quality of blast furnace cast iron. It was estab- lished that using fire clay suspension for increasing the mould covering heat conductivity improves significantly pig iron salable condition and filtration refining method decreases iron contamination by nonmetallic inclusions by 50 – 70 %. Key words: blast furnace, cast iron, fire clay, filter, filtering elements INTRODUCTION tically contain water after mould drying with coke gas. Therefore, pig iron salable condition improves signifi- With the development of motor transport industry, cantly. machine-tool building and other machine building Besides, the use of fire clay for mould coverings ex- branches there increased the requirements to the quality cludes claps in dissolution and prevents the lime solu- of blast furnace cast iron. With the use in the cupola tion corroding action when split on the open parts of the mixture of cast iron melted in large-volume furnaces worker’s body, increases the culture of production and with the melting progressive parameters, at machine decreases labor intensity when making solution, as there building plants there became often defective castings is excluded the waste presence up to 30 – 40 % in the with shrinkage defects, friability, cracks. -

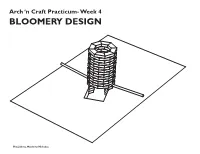

Bloomery Design

Arch ‘n Craft Practicum- Week 4 BLOOMERY DESIGN Hiu, Julieta, Matthew, Nicholas 7 3/4" The Stack: 3 3/4" In our ideal model we would use refractory bricks, either rectangular bricks or curved bricks which would help us make a circular 1'-8" stack. The stack would be around 3 feet tall with a 1 foot diameter for the inner wall of the stack. There will be openings about 3 brick lengths up(6-9 inches) from the ground on 1'-0" opposite ends of the stack. Attached to these openings will be our tuyeres which in turn will connect to our air sources. Building a circular stack would be beneficial to the type of air distribution we want to create within our furnace; using two angled tuyeres we would like air to move clockwise and counterclock- Bloomery Plan wise. We would like to line the inside of the stack with clay to provide further insulation. Refractory bricks would be an ideal material to use because the minerals they are com- posed of do not change chemically when 1'-0" exposed to high heat, some examples of these materials are aluminum, manganese, silica and zirconium. Other comments: 3'-0" Although we have opted to use refractory bricks, which would be practical for our intended purpose, we briefly considered using Vycor glass which can withstand high tem- peratures of up to 900 degrees celsius or approximately 1652 degrees Fahrenheit, which Tuyere height: Pitched -10from horizontal 7" would be enough for our purposes. Bloomery Section Ore/ Charcoal: Our group has decided to use Magnetite ore along with charcoal for the smelt. -

Blast Furnace

RECOMMENDED GUIDELINE FOR IRON & STEEL SECTOR MINISTRY OF STEEL, Doc. No: RG / 04 GOVT. OF INDIA BLAST Rev no.: 00 FURNACE Effective Date: -- 1. OBJECTIVE Blast furnace produces Hot metal (Liquid Iron) using Iron ore, Coke, Sinter, Pellets and fluxes such as Lime-stone, Pyroxenite, Quartzite reacting with oxygen from pre heated air. This entire process of production of hot metal is associated with various safety hazards like hit / entanglement with mobile equipment, burns, fire, slip & fall, exposure to dust, smoke, noise, heat & gas etc. 2. SCOPE This code of safety is applicable to Blast furnace Dept. of an Integrated Steel Plant. 3. PROCESS In the Blast Furnaces (BF) liquid iron (popularly termed as ‘Hot Metal’) is produced by the process of reduction at high temperature from raw materials like iron ore, base mix, sinter, coke, fluxes (limestone / quartzite), etc. &also air blast / O2. In blast furnace the process is also known as “Counter current process” as solid raw material is being charged from the top and hot air is being blown from bottom. During the process the impurities are removed in the form of slag and hot metal is produced. Coal is being injected to reduce consumption of main fuel coke which is a cost reduction measure. Liquid metal and slag are being separated in the area known as cast house. The liquid Hot Metal is transported in Hot Metal Ladles / Torpedoes to the Steel Melting Shops (SMS) for the production of steel by the process of oxidation of the Hot Metal in specially designed Convertors. Sometimes the Hot Metal is poured in the Pig Casting Machine (PCM) to produce Pig Iron. -

Decarbonising Steelmaking: Technology Options and Regional Pathways

Decarbonising steelmaking: technology options and regional pathways Huw McKay Chief Economist Ben Ellis Head of Marketing Strategy and Technical Marketing Wenjun Bao Manager Steel and Nonferrous Analysis Lee Levkowitz Manager Energy and Technology Research 11 November 2020 Disclaimer Forward-looking statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements, including statements regarding: trends in commodity prices and currency exchange rates; demand for commodities; production forecasts; plans, strategies and objectives of management; closure or divestment of certain assets, operations or facilities (including associated costs); anticipated production or construction commencement dates; capital costs and scheduling; operating costs and shortages of materials and skilled employees; anticipated productive lives of projects, mines and facilities; provisions and contingent liabilities; and tax and regulatory developments. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of terminology, including, but not limited to, ‘intend’, ‘aim’, ‘project’, ‘anticipate’, ‘estimate’, ‘plan’, ‘believe’, ‘expect’, ‘may’, ‘should’, ‘will’, ‘would’, ‘continue’, ‘annualised’ or similar words. These statements discuss future expectations concerning the results of assets or financial conditions, or provide other forward-looking information. These forward-looking statements are based on the information available as at the date of this release and are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this release. BHP cautions against reliance on any forward-looking statements or guidance, particularly in light of the current economic climate and the significant volatility, uncertainty and disruption arising in connection with COVID-19. -

Copper Staves for Blast Furnaces

KME Germany GmbH & Co. KG Copper staves [EN] for blast furnaces blast for Copper staves Table of contents KME 2 Copper staves - advanced cooling technology 4 Blast furnace cooling 6 Cooling elements 8 Skull formation 9 Furnace revamping 10 Increased working volume 11 Advanced stave engineering 12 Improved "flanged" joint design 13 Copper stave manufacturing 14 Product range and materials 15 Advantages of hot wrought 17 structure copper stave KME offers a unique combination of know-how and experience in all key technologies for the production of high-performance copper staves for blast furnaces. 2 KME Germany GmbH & Co. KG — Copper staves KME KME‘s corporate goal is to develop and manufacture products that meet customer demands, supporting them in finding solutions for their specific applications, and providing services as a long-term partner. KME’s strategy for accomplishing this goal is based on a highly skilled and experienced workforce. KME has the capacity for inventing and developing new materials and innovative production processes, which KME sustains by ongoing advancement and training of its employees as well as the continual improvement of its organisational structures. KME Germany GmbH & Co. KG — Copper staves 3 Copper staves – advanced cooling technology Cast iron staves Stack Copper staves Belly Bosh Tuyere level Hearth Fig. Blast furnace Average heat load 4 KME Germany GmbH & Co. KG — Copper staves Integrated steelworks use blast furnaces as a KME was involved in the development of copper means of supplying pig iron. For high productivity staves from the very beginning and is also the levels to be achieved it is crucial that the down - owner of the basic patent. -

Primary Mill Fabrication

Metals Fabrication—Understanding the Basics Copyright © 2013 ASM International® F.C. Campbell, editor All rights reserved www.asminternational.org CHAPTER 1 Primary Mill Fabrication A GENERAL DIAGRAM for the production of steel from raw materials to finished mill products is shown in Fig. 1. Steel production starts with the reduction of ore in a blast furnace into pig iron. Because pig iron is rather impure and contains carbon in the range of 3 to 4.5 wt%, it must be further refined in either a basic oxygen or an electric arc furnace to produce steel that usually has a carbon content of less than 1 wt%. After the pig iron has been reduced to steel, it is cast into ingots or continuously cast into slabs. Cast steels are then hot worked to improve homogeneity, refine the as-cast microstructure, and fabricate desired product shapes. After initial hot rolling operations, semifinished products are worked by hot rolling, cold rolling, forging, extruding, or drawing. Some steels are used in the hot rolled condition, while others are heat treated to obtain specific properties. However, the great majority of plain carbon steel prod- ucts are low-carbon (<0.30 wt% C) steels that are used in the annealed condition. Medium-carbon (0.30 to 0.60 wt% C) and high-carbon (0.60 to 1.00 wt% C) steels are often quenched and tempered to provide higher strengths and hardness. Ironmaking The first step in making steel from iron ore is to make iron by chemically reducing the ore (iron oxide) with carbon, in the form of coke, according to the general equation: Fe2O3 + 3CO Æ 2Fe + 3CO2 (Eq 1) The ironmaking reaction takes place in a blast furnace, shown schemati- cally in Fig. -

Steelmaking by Electric Arc Furnaces Cleaner, More Efficient

EVRAZ Canadian Steel: Low Carbon Footprint November 2016 Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs) with metal scrap: cleaner, more efficient • EVRAZ Regina utilizes two Electricity Steelmaking EAFs to make up to 1.1 Generation million tons of steel per Energy used CO2 emissions CO2 emissions year kg / ton of steel kWh / ton of steel grams / kWh -79% • Over 91% of steelmaking -64% -81% 2,081 in China is from Blast 4,624 764 Oxygen Furnaces (BOFs), which use iron ore, coking coal, and other inputs • For every one ton of steel scrap made into new steel, over 1,400kg of iron ore, 1,647 740kg of coal, and 120kg 441 147 of limestone are saved Overseas input shipping to China Blast EAF Blast EAF China Canada Furance Furnace Sources: BOF percentage: Worldsteel. Shipping emissions: National Technical University of Athens. Steelmaking: Midrex – Blast Furnace assuming 11% Scrap, EAF Use of 100% scrap. Scrap statistics: Worldsteel. Electricity Generation: IEA 2011 2 EVRAZ cleaner EAFs, Canada’s power generation outpace others Emissions from Steelmaking emissions and energy use energy generation Energy used CO2 emissions CO2 emissions kg / ton of steel kWh / ton of steel grams / kWh -79% -64% 2,081 4,624 -81% 764 1,526 3,419 2,327 476 470 929 1,647 441 147 China Germany Turkey EVRAZ Blast GermanyTurkey EAF China Turkey Germany Canada - BOF Canada Furnace - EAF - China Overseas shipping of inputs Sources: BOF percentage: Worldsteel. Shipping emissions: National Technical University of Athens, from China to BC, Europe to Houston. Steelmaking: Midrex – Blast Furnace assuming 11% Scrap, EAF Use of 100% scrap. -

The Future of Steelmaking– Howeuropean the MANAGEMENT SUMMARY

05.2020 The future of steelmaking – How the European steel industry can achieve carbon neutrality MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The future of steelmaking / How the European steel industry can achieve carbon neutrality The European steelmaking industry emits 4% of the EU's total CO2 emissions. It is under growing public, economic and regulatory pressure to become carbon neutral by 2050, in line with EU targets. About 60% of European steel is produced via the so-called primary route, an efficient but highly carbon-intensive production method. The industry already uses carbon mitigation techniques, but these are insufficient to significantly reduce or eliminate carbon emissions. The development and implementation of new technologies is underway. With limited investment cycles left until the 2050 deadline, the European steelmaking industry must decide on which new technology to invest in within the next 5-10 years. We assess the most promising emerging technologies in this report. They fall into two main categories: carbon capture, use and/or storage (CCUS), and alternative reduction of iron ore. CCUS processes can be readily integrated into existing steel plants, but cannot alone achieve carbon neutrality. If biomass is used in place of fossil fuels in the steelmaking process, CCUS can result in a negative carbon balance. Alternative reduction technologies include hydrogen-based direct reduction processes and electrolytic reduction methods. Most are not well developed and require huge amounts of green energy, but they hold the promise of carbon-neutral steelmaking. One alternative reduction process, H2-based shaft furnace direct reduction, offers particular promise due to its emissions-reduction potential and state of readiness. -

Blast Furnace Process: Is There Any Alternative?1

ISSN 2176-3135 BLAST FURNACE PROCESS: IS THERE ANY 1 ALTERNATIVE? 2 Ivan Kurunov Abstract Steel-making is globally based on hot metal refining in basic oxygen furnaces. At present and in perspective iron ore and coal remain the main primary materials for iron-making. Available processes of iron-making without a blast furnace are far behind the blast furnace process in terms of productivity and total through-out consumption of fuel for production of hot metal which includes the costs of coke and agglomerated raw materials production, hot blast and oxygen generation. Blast furnace process is the leader in terms of the amount of hot metal production with minimal production cost and in the near future can not only reserve the leading role but significantly reduce the cost for iron-making and the environmental impact. This possibility is related to the prospective use of self-reducing ore and coal briquettes made of concentrate and cheap coal-containing materials in blast furnaces. The process can also be further intensified by using oxygen and increasing the pressure within the furnace. Key words: Blast furnace process; Efficiency; Total fuel rate; Productivity, Alternative processes; Ore and coal briquettes. 1 6th International Congress on the Science and Technology of Ironmaking – ICSTI, 42nd International Meeting on Ironmaking and 13th International Symposium on Iron Ore, October 14th to 18th, 2012, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 2 Novolipetsk Steel, Chief Expert Ironmaking Division, Russia, e-mail: [email protected], tel. +79036437702 114 ISSN 2176-3135 1 INTRODUCTION At present steel is mostly made from hot metal, its percentage in the metallic charge of BOF vessels is 75-95 %, and in EAFs at integrated plants – up to 30-35 %.