2017 Regional Plan of Conservation and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecticut Connections: the Places That Teach Us About Historical Archaeology

CONNECTICUT_CONNECTIONS_THE_PLACES_THAT 2/28/2017 4:13 PM Connecticut Connections: The Places That Teach Us About Historical Archaeology LUCIANNE LAVIN Institute for American Indian Studies To many people the word “archaeology” invokes images of Egyptian pyramids, Aztec temples, the treasures of ancient Rome. If they are aware of North American archaeology, they usually picture archaeology sites far west of New England – 10,000-year-old early man sites on the Plains or the Southwestern Pueblo cliff dwellers. They rarely consider Connecticut as a center of important archaeological activity. But it is! As the preceding articles on Connecticut archaeology aptly illustrate, our state’s rich multi-cultural heritage is reflected and informed by its archaeology sites. Connecticut contains thousands of prehistoric, historic, industrial, and maritime archaeological sites created by the ancestors of its various ethnic residents. Many are thousands of years old. Because Connecticut History is specifically an history journal, I will restrict my discussion to post- European contact archaeology sites. Archaeology sites provide insights on fascinating and important stories about Connecticut that often are not found in local history books. Domestic, commercial, and industrial archaeology sites provide clues to the diverse lifestyles of Connecticut’s residents through time, their community relationships and events, and the cultural changes that modified those lifestyles and connections. But where can one go to learn about Connecticut archaeology? The best places are the sites themselves. Plan an excursion to some of these wonderful archaeology localities where you can spend enjoyable, quality time with family and friends while learning about a specific aspect of local, regional, and even national history. -

Connecticut's Part in the Lexington Alarm By

The f thepomfrettimes1995.org PInformingom the local community retfor 22 years TVolumeimes 23 No.4 JULY 2017 By Connecticut’s Part in the Lexington Alarm Jim Platt n April 19, 1775 the British Perhaps Connecticut’s greatest troops marched contribution to the war was the fact into Lexington, that it furnished many supplies to Massachusetts the Continental Army. To General in an attempt George Washington, Connecticut was Oto capture what they thought “The Provision State”. was an arsenal of powder and shot. The local Militia resisted setts and the rest were sent home. them and the alarm went out A company of horse soldiers were for reinforcements. Throughout formed in Woodstock and they also New England the alarm was spread went to Boston. Each man reported by men on horseback. Israel Bessel to have with him 20 day provisions was charged with spreading the word and 60 rounds of ammunition. The throughout Connecticut and he, like men from Connecticut had on their the other alarmers, rode a horse and standards or flags the motto of “qui carried a drum. By the 27th of April transtulit sustinet” which translates to “God who transplanted us here will the word had reached as far south as It was reported in the diary of one support us.” General Ward was the troop commander in Roxbury and General Baltimore and by the 11th of May it of the local officers that about 1,000 Putnam was the commander in chief and in charge at Cambridge. During the rest of April and May there was no action on either side and had reached Charleston, South Caro- men assembled in Pomfret ready to lina. -

Mary Ellen Jukoski

EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Academic Degrees: Ed.D. The University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee. Curriculum and Instruction, Higher Education, 1983. Dissertation: “Accreditation of Selected Non-Traditional Colleges and Universities.” M.A. College of St. Rose, Albany, New York. English, 1979. M.S. State University of New York at Albany, Albany, New York. Curriculum Planning and Development, 1974. B.A. College of St. Rose, Albany, New York. English/Secondary Education. Cum Laude, 1973. ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE: 1995-Present: President, Mitchell College, New London, Connecticut 1994-1995: Acting President and Academic Vice President, Mitchell College, New London, Connecticut 1990-1995: Academic Vice President and Dean of the College, Mitchell College, New London, Connecticut 1988-1990: Assistant Vice President for Academic Instruction, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut 1985-1988: Dean of Continuing Education, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut 1983-1985: Director, University Without Walls Program, Loretto Heights College, Denver, Colorado 1981-1983: Associate Director, National Institute of Mental Health Federal Grant Project, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 1980-1983: Staff Member, Center for the Study of Higher Education, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 1980-1981: Program Assistant, Institute for Academic Improvement, Center for the Study of Higher Education, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 1979-1980: Assistant Executive Dean, World University-Miami, Miami, Florida 1977-1979: Assistant -

Connecticut Wildlife Jan/Feb 2017

January/February 2017 CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION BUREAU OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISIONS OF WILDLIFE, FISHERIES, AND FORESTRY January/February 2017 Connecticut Wildlife 1 From the Volume 37, Number 1 ● January/February 2017 Director’s Published bimonthly by Desk Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Bureau of Natural Resources Wildlife Division Winter provides a unique, www.ct.gov/deep and sometimes inhospitable, Commissioner Robert Klee window to the natural world around us. While nighttime snowshoeing Deputy Commissioner after a recent snowstorm, my headlamp and a half moon revealed the Susan Whalen Chief, Bureau of Natural Resources travelings of the more adventurous wildlife, with intrepid grey squirrels William Hyatt and white-tailed deer among the more plentiful trail tracks in the snow. Director, Wildlife Division Rick Jacobson More wondrous still is star-gazing on the coldest, clearest nights. Magazine Staff A recent midnight walk with our youngest daughter Amanda was Managing Editor Kathy Herz among the most moving. It was the first time she enjoyed a clear and Production Editor Paul Fusco unblemished view of the Milky Way, and lent to pointing out some of Contributing Editors: Mike Beauchene (Fisheries) Penny Howell (Fisheries) the more prominent constellations – Orion with its noticeable three star Christopher Martin (Forestry) belt and my favorite Canis Major, the greater dog containing Sirius – Circulation Trish Cernik the dog star. Wildlife Division With all of that, Amanda was greatly taken with the most familiar of 79 Elm Street, Hartford, CT 06106-5127 (860-424-3011) Office of the Director, Recreation Management, Technical Assistance, constellations – the Big Dipper – and the ability to follow the outer lip Natural History Survey of the dipper to the North Star. -

2020 – June 30, 2021

TOWN OF STONINGTON, CONNECTICUT ADOPTED BUDGET For the Fiscal Year July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021 In accordance with Governor Lamont’s executive order 7HH the Annual Town Meeting was not held this year. The budget and mil rate were adopted at a joint special virtual meeting of the Board of Selectmen and Board of Finance on Tuesday, May 12, 2020. TOWN OF STONINGTON TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020-2021 ADOPTED BUDGET PAGE BUDGET MESSAGE INTRODUCTION Budget Calendar 1 Town Information & Demographics 2 Building Permits 8 Top Ten Taxpayers 9 Principal Officials 10 Organization Chart 11 Property Tax on a Residential Home with a Median Market Value of $315,800 12 Property Tax Revenue per Capita 13 Revenue/Expenditure Pie Charts 14 Fund Balance History 16 Mill Rate Calculation 17 Mill Rate Impact Summary 18 Revenue Summary 19 Expenditure Summary 21 FIRST SELECTMAN Office of Selectman 35 Programs & Agencies 35 Waterfront Commission 36 Pawcatuck River Harbor Management 36 Shellfish Commission 36 Economic Development Commission 36 Commission to Study Needs & Use of Town Buildings 37 Beautification Committee 37 Charter Revision Committee 37 Emergency Management 37 Elections 38 Town Clerk 39 Town Meeting & Referenda 39 Payments to Other Civil Divisions 39 DEPARTMENT OF ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES Administrative Services 42 Information Systems 43 Human Resources 44 Health Officer and Sanitarian 45 Community Development 45 TOWN OF STONINGTON TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020-2021 ADOPTED BUDGET PAGE DEPARTMENT OF ASSESSMENT Assessor’s Office 51 Board of Assessment Appeals 51 -

Public Act 13-247

House Bill No. 6706 Public Act No. 13-247 AN ACT IMPLEMENTING PROVISIONS OF THE STATE BUDGET FOR THE BIENNIUM ENDING JUNE 30, 2015 CONCERNING GENERAL GOVERNMENT. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Assembly convened: Section 1. (Effective July 1, 2013) The following sums are appropriated from the GENERAL FUND for the annual periods indicated for the purposes described. 2013-2014 2014-2015 LEGISLATIVE LEGISLATIVE MANAGEMENT Personal Services $47,745,867 $50,395,341 Other Expenses 16,130,406 17,168,117 Equipment 107,285 50,100 Flag Restoration 75,000 75,000 Interim Salary/Caucus Offices 605,086 495,478 Connecticut Academy of Science and 500,000 400,000 Engineering Old State House 555,950 581,500 Interstate Conference Fund 383,747 399,080 New England Board of Higher Education 192,938 202,584 Nonfunctional - Change to Accruals 309,233 295,053 AGENCY TOTAL 66,605,512 70,062,253 House Bill No. 6706 AUDITORS OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS Personal Services 11,287,145 11,860,523 Other Expenses 426,778 439,153 Equipment 10,000 10,000 Nonfunctional - Change to Accruals 68,686 69,637 AGENCY TOTAL 11,792,609 12,379,313 COMMISSION ON AGING Personal Services 395,673 417,627 Other Expenses 37,418 38,848 Nonfunctional - Change to Accruals 7,901 2,499 AGENCY TOTAL 440,992 458,974 PERMANENT COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN Personal Services 513,111 543,032 Other Expenses 78,834 57,117 Equipment 1,000 1,000 Nonfunctional - Change to Accruals 5,476 3,588 AGENCY TOTAL 598,421 604,737 COMMISSION ON CHILDREN Personal Services 630,416 670,356 Other Expenses 76,187 77,055 Nonfunctional - Change to Accruals 9,431 5,062 AGENCY TOTAL 716,034 752,473 LATINO AND PUERTO RICAN AFFAIRS COMMISSION Personal Services 400,430 419,433 Other Expenses 63,980 28,144 Nonfunctional - Change to Accruals 6,351 2,457 AGENCY TOTAL 470,761 450,034 Public Act No. -

Metropolitan Transportation Plan (2019-2045)

SOUTHEASTERN CONNECTICUT METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION PLAN FY 2019-2045 ADOPTED: March 20, 2019 SOUTHEASTERN CONNECTICUT COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS SOUTHEASTERN CONNECTICUT METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION PLAN FY 2019-2045 ADOPTED: March 20, 2019 Prepared by the Southeastern Connecticut Council of Governments in cooperation with the Connecticut Department of Transportation, U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Transit Administration. 5 Connecticut Avenue Norwich, CT 06360 Southeastern Connecticut Council of Governments Representatives: Town of BOZRAH Glenn Pianka, First Selectman Town of COLCHESTER Art Shilosky, First Selectman Town of EAST LYME Mark Nickerson, First Selectman Town of FRANKLIN Charles Grant, First Selectman Town of GRISWOLD Todd Babbitt, First Selectman Borough of JEWETT CITY Alan Geer, Warden City of GROTON Keith Hedrick, Mayor Town of GROTON Patrice Granatosky, Mayor, alternate John Burt, Town Manager Town of LEBANON Betsy Petrie, First Selectman Town of LEDYARD Fred Allyn, III, Mayor Town of LISBON Thomas Sparkman, First Selectman Town of MONTVILLE Ron McDaniel, Mayor City of NEW LONDON Michael Passero, Mayor Town of NORTH STONINGTON Michael Urgo, First Selectman City of NORWICH Peter Nystrom, Mayor, alternate John Salomone, City Manager Town of PRESTON Robert Congdon, First Selectman Town of SALEM Kevin Lyden, First Selectman Town of SPRAGUE Catherine Osten, First Selectman Town of STONINGTON Rob Simmons, First Selectman Borough of STONINGTON Jeffrey Callahan, Warden Town of WATERFORD Daniel Steward, First Selectman Town of WINDHAM Victor Funderburk, Mayor, alternate Jim Rivers, Town Manager Staff Assisting in the Preparation of this Report Sam Alexander, AICP, Planner II James S. Butler, AICP, Executive Director Liz Crutcher, GIS Coordinator Amanda Kennedy, AICP, Assistant Director/Director of Special Projects Wendy Leclair, Office Manager Justin LaFountain, Planner II Carly Myers, AICP, Planner II Katherine D. -

Continuity and Variability in Lithic Use During the Woodland Period In

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Master's Theses University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-12-2019 Continuity and Variability in Lithic Use During the Woodland Period in Coastal Southern New England: The iewV from the Laurel Beach II Site Daniel Zoto [email protected] Recommended Citation Zoto, Daniel, "Continuity and Variability in Lithic Use During the Woodland Period in Coastal Southern New England: The ieV w from the Laurel Beach II Site" (2019). Master's Theses. 1386. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/gs_theses/1386 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Connecticut Graduate School at OpenCommons@UConn. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenCommons@UConn. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Continuity and Variability in Lithic Use During the Woodland Period in Coastal Southern New England: The View from the Laurel Beach II Site Daniel M. Zoto B.A., University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2010 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts At the University of Connecticut 2019 i Copyright by Daniel M. Zoto 2019 ii APPROVAL PAGE Masters of Arts Thesis Continuity and Variability in Lithic Use during the Woodland Period in Coastal Southern New England: The View from the Laurel Beach II Site Presented by Daniel M. Zoto, BA University of Connecticut 2019 iii Acknowledgements There are truly far too many people to name that made this project possible. I have learned so much from so many individuals over the years, all of which has influenced this work. -

Illlllllillllilil;; CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) to the PUBLIC

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Connecticut COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES New London INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) COMMON: Fort Griswold AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Bounded by Baker Avenue. Smith Street« Park Aven jand. the CITY OR TOWN: Grot on COUNTY: Connecticut 0 New ODT Illlllllillllilil;; CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building E Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: 1 1 Restricted Site Q Structure D Private Q] In Process Unoccupied1 1 . j ' — ' r> . icl Unrestricted D Object D Both | | Being Consi< Preservation work -^^ in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government 09 Park I | Transportation f~l Comments [^] Commercial D Industrial | | Private Residence Q Other CS [~| Educational 1 1 Military I I Religious | | Entertainment CD Museum I | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: ATE State of Connecticut __ state Park and Forest Commission Connecticut STREET AND NUMBER: St.atft Offinft Rn-nding CTY OR TOWN: STATE: ~ot>'CODE Hartford Connecticut COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Municipal Building TY:UN STREET AND NUMBER: ewLondon Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE Groton Connecticut Tl tt-E OF SURVEY: Connecticut Historic Structures and Landmarks Survey DATE OF SURVEY: m D Federal State County Loca DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Connecticut Historical Commission STREET AND NUMBER: o 75 Sim Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Hartford C onnect icut C& 0 (Check One) CD Excellent ED Good CD. Fair S Deteriorated a Ruins ED Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) [jj) Altered CD Unaltered ED Moved Q?J Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Fort Griswold was built between 1775 s-nd 78 for the defense of the Groton and New London shore. -

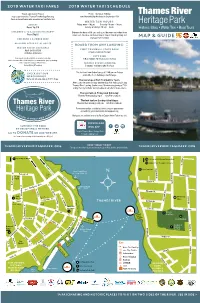

Thames River Heritage Park GO to DONATE on OUR WEBSITE

2019 WATER TAXI FARES 2019 WATER TAXI SCHEDULE Tickets and Season Passes Friday – Sunday & holidays may be purchased at ThamesRiverHeritagePark.org. from Memorial Day Weekend to September 15th Cash and credit cards also accepted on the Water Taxi. WATER TAXI HOURS: ADULTS Friday: noon – 10 p.m. Saturday: 10 a.m. – 10 p.m. Round Trip $10 Sunday & holidays: 10 a.m. – 9 p.m. Historic Sites • Water Taxi • Boat Tours * CHILDREN 4-12 & ACTIVE MILITARY Between the hours of 10 a.m. and 7 p.m. the water taxi makes three ONE RIVER. A THOUSAND STO- Round Trip $5 stops each hour in a continuous hop on-hop off loop beginning and MAP & GUIDE CHILDREN 3 & UNDER FREE ending at Fort Trumbull. ALL RIDES AFTER 6 P.M. ARE $5 BOARD FROM ANY LANDING: SEASON PASSES AVAILABLE FORT TRUMBULL STATE PARK Adult $50 Child $30 in New London: on the hour All Rides, All Season CITY PIER Passengers may disembark & re-board at each stop. in New London: 20 minutes after the hour Water Taxi runs rain or shine. Bicycles accommodated, space permitting. Rates subject to change without notice. THAMES RIVER LANDING *Active Military ID required. in Groton: 40 minutes after the hour CHECK OUT OUR The first boat from Groton leaves at 11:40 a.m. on Fridays and 9:40 a.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. MERCHANDISE. Go to our site and click on TRHP Shop. The last stop at Fort Trumbull is 7 p.m. After 7 p.m. the water taxi runs between City Pier, New London and Thames River Landing, Groton every 20 minutes beginning at 7:20 at City Pier. -

Town of Stonington, Connecticut $20,000,000 General Obligation Bonds, Issue of 2017

Final Official Statement Dated October 19, 2017 NEW MONEY ISSUE: Book-Entry-Only Ratings: S&P Global Ratings: “AA+ / SP1+” In the opinion of Bond Counsel, based on existing statutes and court decisions and assuming continuing compliance with certain covenants and procedures relating to requirements of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), interest on the Bonds and the Notes is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes and is not treated as an item of tax preference for purposes of computing the federal alternative minimum tax. Interest on the Bonds and the Notes may be includable in the calculation of certain taxes under the Code, including the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on certain corporations. In the opinion of Bond Counsel, based on existing statutes, interest on the Bonds and the Notes is excluded from Connecticut taxable income for purposes of the Connecticut income tax on individuals, trusts and estates, and is excluded from amounts on which the net Connecticut minimum tax is based in the case of individuals, trusts and estates required to pay the federal alternative minimum tax. See “Tax Matters” herein. Town of Stonington, Connecticut $20,000,000 General Obligation Bonds, Issue of 2017 Dated: Date of Delivery Due: Serially November 1, 2018 – 2037, As detailed on the inside cover: Interest on the Bonds will be payable on November 1, 2018 and semiannually thereafter on May 1 and November 1 in each year until maturity. The Bonds will be issued by means of a book-entry-only system and registered in the name of Cede & Co., as nominee for the Depository Trust Company (“DTC”) New York, New York. -

Connecticut State Parks System

A Centennial Overview 1913-2013 www.ct.gov/deep/stateparks A State Park Centennial Message from Energy and Environmental Protection Commissioner Robert J. Klee Dear Friends, This year, we are celebrating the Centennial of the Connecticut State Parks system. Marking the 100th anniversary of our parks is a fitting way to pay tribute to past conservation-minded leaders of our state, who had the foresight to begin setting aside important and scenic lands for public access and enjoyment. It is also a perfect moment to commit ourselves to the future of our park system – and to providing first-class outdoor recreation opportunities for our residents and visitors well into the future. Our park system had humble beginnings. A six-member State Park Commission was formed by then Governor Simeon Baldwin in 1913. One year later the Commission purchased its first land, about four acres in Westport for what would become Sherwood Island State Park. Today, thanks to the dedication and commitment of many who have worked in the state park system over the last century, Connecticut boasts a park system of which we can all be proud. This system includes 107 locations, meaning there is a park close to home no matter where you live. Our parks cover more than 32,500 acres and now host more than eight million visitors a year – and have hosted a remarkable total of more than 450 million visitors since we first began counting in 1919. Looking beyond the statistics, our parks offer fantastic opportunities for families to spend time outdoors together. They feature swimming, boating, hiking, picnicking, camping, fishing – or simply the chance to enjoy the world of nature.