Endangered Species and Essential Fish Habitat Biological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Master Document Draft EFH EIS Gulf

Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Generic Essential Fish Habitat Amendment to the following fishery management plans of the Gulf of Mexico (GOM): SHRIMP FISHERY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO RED DRUM FISHERY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO REEF FISH FISHERY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO STONE CRAB FISHERY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO CORAL AND CORAL REEF FISHERY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO SPINY LOBSTER FISHERY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO AND SOUTH ATLANTIC COASTAL MIGRATORY PELAGIC RESOURCES OF THE GULF OF MEXICO AND SOUTH ATLANTIC VOLUME 1: TEXT March 2004 Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council The Commons at Rivergate 3018 U.S. Highway 301 North, Suite 1000 Tampa, Florida 33619-2266 Tel: 813-228-2815 (toll-free 888-833-1844), FAX: 813-225-7015 E-mail: [email protected] This is a publication of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA17FC1052. COVER SHEET Environmental Impact Statement for the Generic Essential Fish Habitat Amendment to the fishery management plans of the Gulf of Mexico Draft () Final (X) Type of Action: Administrative (x) Legislative ( ) Area of Potential Impact: Areas of tidally influenced waters and substrates of the Gulf of Mexico and its estuaries in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida extending out to the limit of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Agency: HQ Contact: Region Contacts: U.S. Department of Commerce Steve Kokkinakis David Dale NOAA Fisheries NOAA-Strategic Planning (N/SP) (727)570-5317 Southeast Region Building SSMC3, Rm. 15532 David Keys 9721 Executive Center Dr. -

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay

Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay Final Report Prepared for California Department of Fish & Game Oil Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR) 425 G Executive Court North Fairfield, CA 94534-4019 Prepared by Dagmar Schmidt Etkin, PhD Environmental Research Consulting 41 Croft Lane Cortlandt Manor, NY 10567-1160 SSEP Contract No. P0775013 30 September 2009 Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay Final Report Prepared by Dagmar Schmidt Etkin, PhD Environmental Research Consulting 41 Croft Lane Cortlandt Manor, NY 10567-1160 USA Prepared at the Request of Carl Jochums California Department of Fish & Game Oil Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR) 425 G Executive Court North Fairfield, CA 94534-4019 Submitted to Bruce Joab, SSEP Coordinator and Contract Manager Office of Spill Prevention and Response CA Department of Fish and Game 1700 K Street, Suite 250 Sacramento, CA 95811 Phone 916-322-7561 SSEP Contract No. PO775013 Note: This study was conducted in collaboration with Applied Science Associates (ASA), Inc., of South Kingston, RI, under SSEP Contract No. PO775010. ASA submitted a separate Final Report entitled Transport and Impacts of Oil Spills in San Francisco Bay – Implications for Response. i Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Sausalito's Vision for 2040

The introductory chapter provides an overview of the General Plan, describing the purpose of the plan and its role for the City of Sausalito. The Introduction includes Sausalito’s Vision for 2040, the Authority and Purpose, Organization of the Sausalito General Plan, Implementation of the Plan, Public Participation in Creating the Plan, Sausalito’s History, and Future Trends and Assumptions. SAUSALITO’S VISION FOR 2040 VISION STATEMENT Sausalito is a thriving, safe, and friendly community that sustainably cultivates its natural beauty, history, and its arts and waterfront culture. Due to sea level rise and the continuing effects of climate change, the city seeks to bridge the compelling features and attributes of the city’s past, particularly its unique shoreline neighborhoods, with the environmental inevitabilities of its future. Sausalito embraces environmental stewardship and is dedicated to climate leadership while it strives to conserve the cultural, historic, artistic, business and neighborhood diversity and character that make up the Sausalito community. OVERALL COMMUNITY GOALS The General Plan Update addresses the new and many continuing issues confronting the city since the General Plan was adopted in 1995. The General Plan Update also responds to the many changing conditions of the region, county, and city since the beginning of the 21st century. The following eleven broad goals serve as the basis for more specific policies and implementation strategies. 1. Maintain Sausalito’s small-scale residential neighborhoods, recognizing their geographical, architectural, and cultural diversity, while supporting a range of housing options. 2. Recognize and perpetuate the defining characteristics of Sausalito, including its aesthetic beauty, scenic features, natural and built environment, its history, and its diverse culture. -

Ovarian Development of the Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain in a Tropical Mangrove Swamps, Thailand

Available Online JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Publications J. Sci. Res. 2 (2), 380-389 (2010) www.banglajol.info/index.php/JSR Ovarian Development of the Mud Crab Scylla paramamosain in a Tropical Mangrove Swamps, Thailand M. S. Islam1, K. Kodama2, and H. Kurokura3 1Department of Aquaculture and Fisheries, Jessore Science and Technology University, Jessore- 7407, Bangladesh 2Marine Science Institute, The University of Texas at Austin, Channel View Drive, Port Aransas, Texas 78373, USA 3Laboratory of Global Fisheries Science, Department of Global Agricultural Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan Received 15 October 2009, accepted in revised form 21 March 2010 Abstract The present study describes the ovarian development stages of the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain from Pak Phanang mangrove swamps, Thailand. Samples were taken from local fishermen between June 2006 and December 2007. Ovarian development was determined based on both morphological appearance and histological observation. Ovarian development was classified into five stages: proliferation (stage I), previtellogenesis (II), primary vitellogenesis (III), secondary vitellogenesis (IV) and tertiary vitellogenesis (V). The formation of vacuolated globules is the initiation of primary vitellogenesis and primary growth. The follicle cells were found around the periphery of the lobes, among the groups of oogonia and oocytes. The follicle cells were hardly visible at the secondary and tertiary vitellogenesis stages. Yolk granules occurred in the primary vitellogenesis stage and are first initiated in the inner part of the oocytes, then gradually concentrated to the periphery of the cytoplasm. The study revealed that the initiation of vitellogenesis could be identified by external observation of the ovary but could not indicate precisely. -

BAYLANDS & CREEKS South San Francisco

Oak_Mus_Baylands_SideA_6_7_05.pdf 6/14/2005 11:52:36 AM M12 M10 M27 M10A 121°00'00" M28 R1 For adjoining area see Creek & Watershed Map of Fremont & Vicinity 37°30' 37°30' 1 1- Dumbarton Pt. M11 - R1 M26 N Fremont e A in rr reek L ( o te C L y alien a o C L g a Agua Fria Creek in u d gu e n e A Green Point M a o N l w - a R2 ry 1 C L r e a M8 e g k u ) M7 n SF2 a R3 e F L Lin in D e M6 e in E L Creek A22 Toroges Slou M1 gh C ine Ravenswood L Slough M5 Open Space e ra Preserve lb A Cooley Landing L i A23 Coyote Creek Lagoon n M3 e M2 C M4 e B Palo Alto Lin d Baylands Nature Mu Preserve S East Palo Alto loug A21 h Calaveras Point A19 e B Station A20 Lin C see For adjoining area oy Island ote Sand Point e A Lucy Evans Lin Baylands Nature Creek Interpretive Center Newby Island A9 San Knapp F Map of Milpitas & North San Jose Creek & Watershed ra Hooks Island n Tract c A i l s Palo Alto v A17 q i ui s to Creek Baylands Nature A6 o A14 A15 Preserve h g G u u a o Milpitas l Long Point d a S A10 A18 l u d p Creek l A3N e e i f Creek & Watershed Map of Palo Alto & Vicinity Creek & Watershed Calera y A16 Berryessa a M M n A1 A13 a i h A11 l San Jose / Santa Clara s g la a u o Don Edwards San Francisco Bay rd Water Pollution Control Plant B l h S g Creek d u National Wildlife Refuge o ew lo lo Vi F S Environmental Education Center . -

Oakland Coliseum Industrial Center 5800 Coliseum Way | Oakland, CA

Premier Urban Logistics Location Oakland Coliseum Industrial Center 5800 Coliseum Way | Oakland, CA ±336,680 SF Warehouse For Lease Jason Ovadia Patrick Metzger Greg Matter Jason Cranston Robert Bisnette +1 510 285 5360 +1 510 285 5362 650 480 2220 [email protected] +1 510 661 4011 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] +1 650 480 2100 [email protected] Lic # 01742912 Lic # 01888895 Lic #01380731 Lic # 01253892 Lic # 01474433 Jones Lang LaSalle Brokerage, Inc. Real Estate License # 01856260 Unrivaled Access to Bay80 Area Urban Core 80 Vallejo Port of Benecia 80 Concord San Rafael Richmond Port of 101 Richmond 580 Walnut Creek Oakland 680 Port of Oakland Prologis Oakland Coliseum San Francisco Urban Logistics Center Port of San Francisco Oakland International Airport PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Hayward 580 Pleasanton San Francisco • Close proximity to Oakland Airport and International Airport Port of Oakland Fremont • Overweight accessible location San Mateo 880 • Great access to robust workforce 280 101 • Union Pacific Rail capabilities Driving distance Palo Alto • Heavy Power with Back Up Generator 3.5 mi Oakland International Airport 680 5.3 mi Port of Oakland San Jose • Divisible to ±168,340 SF International Airport • Available Q4 2020 16.2 mi SF Financial District San Jose 16.2 mi Port of San Francisco 27.5 mi SF International Airport 36.4 mi San Jose International Airport ±336,680 SF Current Building Configuration 80 Warehouse ±336,680 SF Office ±16,380 SF Site Size 9.93 acres Vallejo Column -

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

Sediment Transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: an Overview

Marine Geology 345 (2013) 3–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margeo Sediment transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: An overview Patrick L. Barnard a,⁎, David H. Schoellhamer b,c, Bruce E. Jaffe a, Lester J. McKee d a U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, California Water Science Center, Sacramento, CA, USA c University of California, Davis, USA d San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: The papers in this special issue feature state-of-the-art approaches to understanding the physical processes Received 29 March 2012 related to sediment transport and geomorphology of complex coastal–estuarine systems. Here we focus on Received in revised form 9 April 2013 the San Francisco Bay Coastal System, extending from the lower San Joaquin–Sacramento Delta, through the Accepted 13 April 2013 Bay, and along the adjacent outer Pacific Coast. San Francisco Bay is an urbanized estuary that is impacted by Available online 20 April 2013 numerous anthropogenic activities common to many large estuaries, including a mining legacy, channel dredging, aggregate mining, reservoirs, freshwater diversion, watershed modifications, urban run-off, ship traffic, exotic Keywords: sediment transport species introductions, land reclamation, and wetland restoration. The Golden Gate strait is the sole inlet 9 3 estuaries connecting the Bay to the Pacific Ocean, and serves as the conduit for a tidal flow of ~8 × 10 m /day, in addition circulation to the transport of mud, sand, biogenic material, nutrients, and pollutants. -

Section 8: the Current Permitting Process for Projects Proposed on San Francisquito Creek

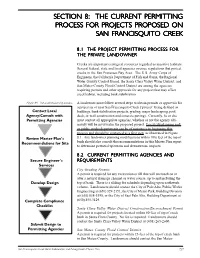

SECTION 8: THE CURRENT PERMITTING PROCESS FOR PROJECTS PROPOSED ON SAN FRANCISQUITO CREEK 8.1 THE PROJECT PERMITTING PROCESS FOR THE PRIVATE LANDOWNER Creeks are important ecological resources regarded as sensitive habitats. Several federal, state and local agencies oversee regulations that protect creeks in the San Francisco Bay Area. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the California Department of Fish and Game, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, the Santa Clara Valley Water District, and San Mateo County Flood Control District are among the agencies requiring permits and other approvals for any project that may affect creek habitat, including bank stabilization. Figure 8A The project planning process A landowner must follow several steps to obtain permits or approvals for a project in or near San Francisquito Creek (‘project’ being defined as Contact Local buildings, bank stabilization projects, grading, major landscaping, pool, Agency/Consult with deck, or wall construction and concrete paving). Currently, he or she Permitting Agencies must contact all appropriate agencies, whether or not the agency ulti- mately will be involved in the proposed project. Local city planning and/ or public works departments can be of assistance in beginning this process and should be contacted as a first step, as illustrated in Figure Review Master Plan’s 8.1. Any landowner planning modifications within fifty feet of the top of Recommendations for Site bank should also consult the recommendations in this Master Plan report to determine potential upstream and downstream impacts. 8.2 CURRENT PERMITTING AGENCIES AND Secure Engineer’s REQUIREMENTS Services City Grading Permits A permit is required for any excavation or fill that will encroach on or alter a natural drainage channel or water course, up to and including the Develop Design top of bank. -

NMFS 2010 Essential Fish Habitat, TN186

Essential Fish Habitat: A Marine Fish Habitat Conservation Mandate For Federal Agencies Gulf of Mexico Region National Marine Fisheries Service Habitat Conservation Division Southeast Regional Office 263 13th Avenue S. St. Petersburg, FL 33701 727/824-5317 REV. 09/2010 1 Executive Summary The 1996 amendments to the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Magnuson-Stevens Act) set forth a new mandate for NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), regional fishery management councils (FMC), and other federal agencies to identify and protect important marine and anadromous fish habitat. The essential fish habitat (EFH) provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Act support one of the nation’s overall marine resource management goals - maintaining sustainable fisheries. Essential to achieving this goal is the maintenance of suitable marine fishery habitat quality and quantity. The FMCs, with assistance from NMFS, have delineated EFH for federally managed species. As new fishery management plans (FMPs) are developed, EFH for newly managed species will be defined as well. Federal action agencies which fund, permit, or carry out activities that may adversely affect EFH are required to consult with NMFS regarding the potential impacts of their actions on EFH and respond in writing to NMFS or FMC recommendations. In addition, NMFS and the FMCs may comment on and make recommendations to any state agency on their activities that may affect EFH. Measures recommended by NMFS or an FMC to protect EFH are advisory, not proscriptive. On December 19, 1997, interim final rules, which specified procedures for implementation of the EFH provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Act, were published in the Federal Register. -

Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

SDMS DOCID# 1137835 BAY FILL IN SAN FRANCISCO: A HISTORY OF CHANGE A thesis submitted to the faculty of California State University, San Francisco in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Gerald Robert Dow Department of Geography July 1973 Permission is granted for the material in this thesis to be reproduced in part or whole for the purpose of education and/or research. It may not be edited, altered, or otherwise modified, except with the express permission of the author. - ii - - ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Maps . vi INTRODUCTION . .1 CHAPTER I: JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES OF SAN FRANCISCO’S TIDELANDS . .4 Definition of Tidelands . .5 Evolution of Tideland Ownership . .5 Federal Land . .5 State Land . .6 City Land . .6 Sale of State Owned Tidelands . .9 Tideland Grants to Railroads . 12 Settlement of Water Lot Claims . 13 San Francisco Loses Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 14 San Francisco Regains Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 15 The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Port of San Francisco . 18 CHAPTER II: YERBA BUENA COVE . 22 Introduction . 22 Yerba Buena, the Beginning of San Francisco . 22 Yerba Buena Cove in 1846 . 26 San Francisco’s First Waterfront . 26 Filling of Yerba Buena Cove Begins . 29 The Board of State Harbor Commissioners and the First Seawall . 33 The New Seawall . 37 The Northward Expansion of San Francisco’s Waterfront . 40 North Beach . 41 Fisherman’s Wharf . 43 Aquatic Park . 45 - iii - Pier 45 . 47 Fort Mason . 48 South Beach . 49 The Southward Extension of the Great Seawall .