Crangon Franciscorum Class: Multicrustacea, Malacostraca, Eumalacostraca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Neaxius Acanthus

Wattenmeerstation Sylt The role of Neaxius acanthus (Thalassinidea: Strahlaxiidae) and its burrows in a tropical seagrass meadow, with some remarks on Corallianassa coutierei (Thalassinidea: Callianassidae) Diplomarbeit Institut für Biologie / Zoologie Fachbereich Biologie, Chemie und Pharmazie Freie Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Dominik Kneer Angefertigt an der Wattenmeerstation Sylt des Alfred-Wegener-Instituts für Polar- und Meeresforschung in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Center for Coral Reef Research der Hasanuddin University Makassar, Indonesien Sylt, Mai 2006 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Thomas Bartolomaeus Institut für Biologie / Zoologie Freie Universität Berlin Berlin 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Walter Traunspurger Fakultät für Biologie / Tierökologie Universität Bielefeld Bielefeld Meinen Eltern (wem sonst…) Table of contents 4 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Zusammenfassung...................................................................................................................... 8 Abstrak ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... 12 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... -

Prawn Fauna (Crustacea: Decapoda) of India - an Annotated Checklist of the Penaeoid, Sergestoid, Stenopodid and Caridean Prawns

Available online at: www.mbai.org.in doi: 10.6024/jmbai.2012.54.1.01697-08 Prawn fauna (Crustacea: Decapoda) of India - An annotated checklist of the Penaeoid, Sergestoid, Stenopodid and Caridean prawns E. V. Radhakrishnan*1, V. D. Deshmukh2, G. Maheswarudu3, Jose Josileen 1, A. P. Dineshbabu4, K. K. Philipose5, P. T. Sarada6, S. Lakshmi Pillai1, K. N. Saleela7, Rekhadevi Chakraborty1, Gyanaranjan Dash8, C.K. Sajeev1, P. Thirumilu9, B. Sridhara4, Y Muniyappa4, A.D.Sawant2, Narayan G Vaidya5, R. Dias Johny2, J. B. Verma3, P.K.Baby1, C. Unnikrishnan7, 10 11 11 1 7 N. P. Ramachandran , A. Vairamani , A. Palanichamy , M. Radhakrishnan and B. Raju 1CMFRI HQ, Cochin, 2Mumbai RC of CMFRI, 3Visakhapatnam RC of CMFRI, 4Mangalore RC of CMFRI, 5Karwar RC of CMFRI, 6Tuticorin RC of CMFRI, 7Vizhinjam RC of CMFRI, 8Veraval RC of CMFRI, 9Madras RC of CMFRI, 10Calicut RC of CMFRI, 11Mandapam RC of CMFRI *Correspondence e-mail: [email protected] Received: 07 Sep 2011, Accepted: 15 Mar 2012, Published: 30 Apr 2012 Original Article Abstract Many penaeoid prawns are of considerable value for the fishing Introduction industry and aquaculture operations. The annual estimated average landing of prawns from the fishery in India was 3.98 The prawn fauna inhabiting the marine, estuarine and lakh tonnes (2008-10) of which 60% were contributed by freshwater ecosystems of India are diverse and fairly well penaeid prawns. An additional 1.5 lakh tonnes is produced from known. Significant contributions to systematics of marine aquaculture. During 2010-11, India exported US $ 2.8 billion worth marine products, of which shrimp contributed 3.09% in prawns of Indian region were that of Milne Edwards (1837), volume and 69.5% in value of the total export. -

Suisun Marsh Fish Report 2015 Final

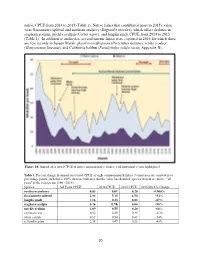

native CPUE from 2014 to 2015 (Table 1). Native fishes that contributed most to 2015's value were Sacramento splittail and northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax), which offset declines in staghorn sculpin, prickly sculpin (Cottus asper), and longfin smelt CPUE from 2014 to 2015 (Table 1). In addition to anchovies, several marine fishes were captured in 2016 for which there are few records in Suisun Marsh: plainfin midshipman (Porichthys notatus), white croaker (Genyonemus lineatus), and California halibut (Paralichthys californicus; Appendix B). Figure 14. Annual otter trawl CPUE of native and non-native fishes, with important events highlighted. Table 1. Percent change in annual otter trawl CPUE of eight common marsh fishes (% increases are equivalent to percentage points, such that a 100% increase indicates that the value has doubled; species in bold are native; "all years" is the average for 1980 - 2015). Species All Years CPUE 2014 CPUE 2015 CPUE 2015/2014 % Change northern anchovy 0.03 0.01 0.20 +1900% Sacramento splittail 2.84 5.15 6.90 +34% longfin smelt 1.16 0.23 0.03 -87% staghorn sculpin 0.26 0.16 0.00 -98% prickly sculpin 1.09 0.55 0.20 -64% common carp 0.52 0.49 0.19 -61% white catfish 0.63 0.94 0.43 -54% yellowfin goby 2.31 0.47 0.26 -45% 20 Beach Seines Annual beach seine CPUE in 2015 was similar to the average from 1980 to 2015 (57 fish per seine; Figure 15), declining mildly from 2014 to 2015 (62 and 52 per seine, respectively). CPUE declined slightly for both non-native and native fishes from 2014 to 2015 (Figure 15); as usual, non-native fish, dominated by Mississippi silversides (Menidia audens), were far more abundant in seine hauls than native fish (Table 2). -

Annual Report 2010–2011

Australian Museum 2010–2011 Report Annual Australian Museum Annual Report 2010–2011 Australian Museum Annual Report 2010 – 2011 ii Australian Museum Annual Report 2010 –11 The Australian Museum Annual Report 2010 –11 Availability is published by the Australian Museum Trust, This annual report has been designed for accessible 6 College Street Sydney NSW 2010. online use and distribution. A limited number of copies have been printed for statutory purposes. © Australian Museum Trust 2011 This report is available at: ISSN 1039-4141 www.australianmuseum.net.au/Annual-Reports. Editorial Further information on the research and education Project management: Wendy Rapee programs and services of the Australian Museum Editing and typesetting: Brendan Atkins can be found at www.australianmuseum.net.au. Proofreading: Lindsay Taaffe Design and production: Australian Museum Environmental responsibility Design Studio Printed on Sovereign Offset, an FSC- certified paper from responsibly grown fibres, made under an All photographs © Australian Museum ISO 14001– accredited environmental management 2011, unless otherwise indicated. system and without the use of elemental chlorine. Contact Australian Museum 6 College Street Sydney NSW 2010 Open daily 9.30 am – 5.00 pm t 02 9320 6000 f 02 9320 6050 e [email protected] w www.australianmuseum.net.au www.facebook.com/australianmuseum www.twitter.com/austmus www.youtube.com/austmus front cover: The Museum's after-hours program, Jurassic Lounge, attracted a young adult audience to enjoy art, music and new ideas. Photo Stuart Humphreys. iii Minister The Hon. George Souris, MP and Minister for the Arts Governance The Museum is governed by a Trust established under the Australian Museum Trust Act 1975. -

Prospects of Red King Crab Hepatopancreas Processing: Fundamental and Applied Biochemistry

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 12 September 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202009.0263.v1 Article Prospects of Red King Crab Hepatopancreas Processing: Fundamental and Applied Biochemistry Tatyana Ponomareva 1, Maria Timchenko 1, Michael Filippov 1, Sergey Lapaev 1, and Evgeny Sogorin 1,* 1 Federal Research Center "Pushchino Scientific Center for Biological Research of the RAS", Pushchino, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-915-132-54-19 Abstract: Since the early 1980s, a large number of research works on enzymes from the red king crab hepatopancreas have been conducted. These studies have been relevant both from a fundamental point of view for studying the enzymes of marine organisms and in terms of the rational management of nature to obtain new and valuable products from the processing of crab fishing waste. Most of these works were performed by Russian scientists due to the area and amount of waste of red king crab processing in Russia (or the Soviet Union). However, the close phylogenetic kinship and the similar ecological niches of commercial crab species and the production scale of the catch provide the bases for the successful transfer of experience in the processing of red king crab hepatopancreas to other commercial crab species mined worldwide. This review describes the value of recycled commercial crab species, discusses processing problems, and suggests possible solutions to these problems. The main emphasis is placed on the enzymes of the hepatopancreas as the most highly salubrious product of waste processed from red king crab fishing. Keywords: marine fisheries; aquatic organisms; brachyura; anomura; commercial crab species; red king crab; Kamchatka crab; processing waste; hepatopancreas; waste recycling; enzymes; proteases; hyaluronidase 1. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Lissocrangon Stylirostris Class: Multicrustacea, Malacostraca, Eumalacostraca

Phylum: Arthropoda, Crustacea Lissocrangon stylirostris Class: Multicrustacea, Malacostraca, Eumalacostraca Order: Eucarida, Decapoda, Pleocyemata, Caridea Common shrimp Family: Crangonoidea, Crangonidae Taxonomy: Schmitt (1921) described many stylirostris (Kuris et al. 2007). shrimp in the genus Crago (e.g. Crago alas- Cephalothorax: kensis and C. franciscorum) and reserved Eyes: Small, pigmented and not cov- the genus Crangon for the snapping shrimp ered by carapace. (now in the genus Alpheus). In 1955–56, Antenna: Antennal scale the International Commission on Zoological (scaphocerite) short, just a little over half the Nomenclature formally reserved the genus length of the carapace, blade with oblique in- Crangon for the sand shrimps only. Kuris ner margin; spine longer than blade (Fig. 2). and Carlton (1977) designated the new, and Stylocerite (basal, lateral spine on antennule) currently monotypic, genus Lissocrangon longer than first antennular peduncle segment based on a lack of gastric carapace spines. and blade-like (Wicksten 2011). Known synonyms for L. stylirostris include Mouthparts: The mouth of decapod Crago stylirostris and Crangon stylirostris crustaceans comprises six pairs of appendag- (Wicksten 2011). es including one pair of mandibles (on either side of the mouth), two pairs of maxillae and Description three pairs of maxillipeds. The maxillae and Size: Type specimen 55 mm in body length maxillipeds attach posterior to the mouth and (Ricketts and Calvin 1971) with average extend to cover the mandibles (Ruppert et al. length 30–61 mm (male average 43 mm and 2004). Third maxilliped stout (particularly first female 61 mm, Wicksten 2011; size range segment, which is broadly dilated) and with 20–70 mm for females, 15–49 mm for exopod (Kuris and Carlton 1977; Wicksten males, Marin Jarrin and Shanks 2008). -

California “Epicaridean” Isopods Superfamilies Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea (Crustacea, Isopoda, Cymothoida)

California “Epicaridean” Isopods Superfamilies Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea (Crustacea, Isopoda, Cymothoida) by Timothy D. Stebbins Presented to SCAMIT 13 February 2012 City of San Diego Marine Biology Laboratory Environmental Monitoring & Technical Services Division • Public Utilities Department (Revised 1/18/12) California Epicarideans Suborder Cymothoida Subfamily Phyllodurinae Superfamily Bopyroidea Phyllodurus abdominalis Stimpson, 1857 Subfamily Athelginae Family Bopyridae * Anathelges hyphalus (Markham, 1974) Subfamily Pseudioninae Subfamily Hemiarthrinae Aporobopyrus muguensis Shiino, 1964 Hemiarthrus abdominalis (Krøyer, 1840) Aporobopyrus oviformis Shiino, 1934 Unidentified species † Asymmetrione ambodistorta Markham, 1985 Family Dajidae Discomorphus magnifoliatus Markham, 2008 Holophryxus alaskensis Richardson, 1905 Goleathopseudione bilobatus Román-Contreras, 2008 Family Entoniscidae Munidion pleuroncodis Markham, 1975 Portunion conformis Muscatine, 1956 Orthione griffenis Markham, 2004 Superfamily Cryptoniscoidea Pseudione galacanthae Hansen, 1897 Family Cabiropidae Pseudione giardi Calman, 1898 Cabirops montereyensis Sassaman, 1985 Subfamily Bopyrinae Family Cryptoniscidae Bathygyge grandis Hansen, 1897 Faba setosa Nierstrasz & Brender à Brandis, 1930 Bopyrella calmani (Richardson, 1905) Family Hemioniscidae Probopyria sp. A Stebbins, 2011 Hemioniscus balani Buchholz, 1866 Schizobopyrina striata (Nierstrasz & Brender à Brandis, 1929) Subfamily Argeiinae † Unidentified species of Hemiarthrinae infesting Argeia pugettensis -

First Record of the Introduced Sand Shrimp Species Crangon Uritai

Marine Biodiversity Records, page 1 of 6. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2011 doi:10.1017/S1755267211000248; Vol. 4; e22; 2011 Published online First record of the introduced sand shrimp species Crangon uritai (Decapoda: Caridea: Crangonidae) from Newport, Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Australia joanne taylor1 and tomoyuki komai2 1Museum Victoria, GPO Box 666, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia, 2Natural History Museum and Institute, Chiba, 955-2 Aoba-cho, Chuo-ku, Chiba, 260-8682 Japan Three specimens of the crangonid sand shrimp species Crangon uritai are reported from the muddy intertidal zone of Newport in Port Phillip Bay, Victoria. The discovery of the species in the bay is the first record of the genus Crangon from Australian waters and the first report of the East Asian coastal species Crangon uritai from the southern hemisphere. Its status as an introduced species is suggested and the likely vector for introduction is discussed. A key to the identification of crangonid shrimp species from Port Phillip Bay is included. Keywords: Crustacea, Caridea, Crangonidae, Crangon, introduced species, Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, Australia Submitted 28 December 2010; accepted 28 January 2011 INTRODUCTION is known as the ‘warmies’ by local fishers. The shrimps were distinct from other species of Crangonidae previously The benthic fauna of Port Phillip Bay has been well studied reported from Port Phillip Bay and after comparison with including bay-wide surveys conducted as part of the Port specimens lodged in the Natural History Museum and Phillip Bay environmental studies (Poore et al., 1975; Institute, Chiba, Japan, have been determined as Crangon Wilson et al., 1998). -

Distribution, Abundance, and Diversity of Epifaunal Benthic Organisms in Alitak and Ugak Bays, Kodiak Island, Alaska

DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND DIVERSITY OF EPIFAUNAL BENTHIC ORGANISMS IN ALITAK AND UGAK BAYS, KODIAK ISLAND, ALASKA by Howard M. Feder and Stephen C. Jewett Institute of Marine Science University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 517 October 1977 279 We thank the following for assistance during this study: the crew of the MV Big Valley; Pete Jackson and James Blackburn of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Kodiak, for their assistance in a cooperative benthic trawl study; and University of Alaska Institute of Marine Science personnel Rosemary Hobson for assistance in data processing, Max Hoberg for shipboard assistance, and Nora Foster for taxonomic assistance. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management, Department of the Interior, through an interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, as part of the Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Environment Assessment Program (OCSEAP). SUMMARY OF OBJECTIVES, CONCLUSIONS, AND IMPLICATIONS WITH RESPECT TO OCS OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT Little is known about the biology of the invertebrate components of the shallow, nearshore benthos of the bays of Kodiak Island, and yet these components may be the ones most significantly affected by the impact of oil derived from offshore petroleum operations. Baseline information on species composition is essential before industrial activities take place in waters adjacent to Kodiak Island. It was the intent of this investigation to collect information on the composition, distribution, and biology of the epifaunal invertebrate components of two bays of Kodiak Island. The specific objectives of this study were: 1) A qualitative inventory of dominant benthic invertebrate epifaunal species within two study sites (Alitak and Ugak bays). -

Benvenuto, C and SC Weeks. 2020

--- Not for reuse or distribution --- 8 HERMAPHRODITISM AND GONOCHORISM Chiara Benvenuto and Stephen C. Weeks Abstract This chapter compares two sexual systems: hermaphroditism (each individual can produce gametes of either sex) and gonochorism (each individual produces gametes of only one of the two distinct sexes) in crustaceans. These two main sexual systems contain a variety of alternative modes of reproduction, which are of great interest from applied and theoretical perspectives. The chapter focuses on the description, prevalence, analysis, and interpretation of these sexual systems, centering on their evolutionary transitions. The ecological correlates of each reproduc- tive system are also explored. In particular, the prevalence of “unusual” (non- gonochoristic) re- productive strategies has been identified under low population densities and in unpredictable/ unstable environments, often linked to specific habitats or lifestyles (such as parasitism) and in colonizing species. Finally, population- level consequences of some sexual systems are consid- ered, especially in terms of sex ratios. The chapter aims to provide a broad and extensive overview of the evolution, adaptation, ecological constraints, and implications of the various reproductive modes in this extraordinarily successful group of organisms. INTRODUCTION 1 Historical Overview of the Study of Crustacean Reproduction Crustaceans are a very large and extraordinarily diverse group of mainly aquatic organisms, which play important roles in many ecosystems and are economically important. Thus, it is not surprising that numerous studies focus on their reproductive biology. However, these reviews mainly target specific groups such as decapods (Sagi et al. 1997, Chiba 2007, Mente 2008, Asakura 2009), caridean Reproductive Biology. Edited by Rickey D. Cothran and Martin Thiel. -

Bering Sea Marine Invasive Species Assessment Alaska Center for Conservation Science

Bering Sea Marine Invasive Species Assessment Alaska Center for Conservation Science Scientific Name: Palaemon macrodactylus Phylum Arthropoda Common Name oriental shrimp Class Malacostraca Order Decapoda Family Palaemonidae Z:\GAP\NPRB Marine Invasives\NPRB_DB\SppMaps\PALMAC.pn g 40 Final Rank 49.87 Data Deficiency: 3.75 Category Scores and Data Deficiencies Total Data Deficient Category Score Possible Points Distribution and Habitat: 20 26 3.75 Anthropogenic Influence: 6.75 10 0 Biological Characteristics: 20.5 30 0 Impacts: 0.75 30 0 Figure 1. Occurrence records for non-native species, and their geographic proximity to the Bering Sea. Ecoregions are based on the classification system by Spalding et al. (2007). Totals: 48.00 96.25 3.75 Occurrence record data source(s): NEMESIS and NAS databases. General Biological Information Tolerances and Thresholds Minimum Temperature (°C) 2 Minimum Salinity (ppt) 0.7 Maximum Temperature (°C) 33 Maximum Salinity (ppt) 51 Minimum Reproductive Temperature (°C) NA Minimum Reproductive Salinity (ppt) 3 Maximum Reproductive Temperature (°C) NA Maximum Reproductive Salinity (ppt) 34 Additional Notes Palaemon macrodactylus is commonly known as the Oriental shrimp. Its body is transparent with a reddish hue in the tail fan and antennary area. Females tend to be larger than males and have more pigmentation, with reddish spots all over their body, and a whitish longitudinal stripe that runs along the back. Females reach a maximum size of 45-70 mm, compared to 31.5-45 mm for males (Vazquez et al. 2012, qtd. in Fofnoff et al. 2003). Report updated on Wednesday, December 06, 2017 Page 1 of 13 1.