Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hclassifi Cation

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) WEES UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME Bateria San Josej Punta Medanos; Battery Yerba Buena^ Point San Jose: HISTORIC Black Point; Post of Point San Jose; Fort Mason ,AND/OR COMMON =; — '"-''" Fort Mason LOCATION STREET&NUMBER ,,Qn the water*s edge, Northern San Francisco, bounded by Van Ness- Avenue, Bay -Sfea?e@*% and Laguna Streets,* _NOTFOR PUBLICATION / CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT San Francisco _ VICINITY OF Fifth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 San Francisco 075 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X_DISTRICT X_PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS X_EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED ^.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO X-MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS. (Itapplicable) National Park Service, Western Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 450 Golden Gate Avenue, Box 36063 CITY. TOWN STATE San Francisco VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. San Francisco City Hall STREET & NUMBER Polk and McAllister Streets CITY. TOWN STATE San Francisco California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey, GAL-1119 and CAL 1877-1880 DATE Late 1930 f s and January, 1959 .XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —RUINS -^ALTERED —FAIR _UNEXPOSED (1 moved, 1877) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE 7. -

Sausalito's Vision for 2040

The introductory chapter provides an overview of the General Plan, describing the purpose of the plan and its role for the City of Sausalito. The Introduction includes Sausalito’s Vision for 2040, the Authority and Purpose, Organization of the Sausalito General Plan, Implementation of the Plan, Public Participation in Creating the Plan, Sausalito’s History, and Future Trends and Assumptions. SAUSALITO’S VISION FOR 2040 VISION STATEMENT Sausalito is a thriving, safe, and friendly community that sustainably cultivates its natural beauty, history, and its arts and waterfront culture. Due to sea level rise and the continuing effects of climate change, the city seeks to bridge the compelling features and attributes of the city’s past, particularly its unique shoreline neighborhoods, with the environmental inevitabilities of its future. Sausalito embraces environmental stewardship and is dedicated to climate leadership while it strives to conserve the cultural, historic, artistic, business and neighborhood diversity and character that make up the Sausalito community. OVERALL COMMUNITY GOALS The General Plan Update addresses the new and many continuing issues confronting the city since the General Plan was adopted in 1995. The General Plan Update also responds to the many changing conditions of the region, county, and city since the beginning of the 21st century. The following eleven broad goals serve as the basis for more specific policies and implementation strategies. 1. Maintain Sausalito’s small-scale residential neighborhoods, recognizing their geographical, architectural, and cultural diversity, while supporting a range of housing options. 2. Recognize and perpetuate the defining characteristics of Sausalito, including its aesthetic beauty, scenic features, natural and built environment, its history, and its diverse culture. -

Argonaut #2 2019 Cover.Indd 1 1/23/20 1:18 PM the Argonaut Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society Publisher and Editor-In-Chief Charles A

1/23/20 1:18 PM Winter 2020 Winter Volume 30 No. 2 Volume JOURNAL OF THE SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOL. 30 NO. 2 Argonaut #2_2019_cover.indd 1 THE ARGONAUT Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles A. Fracchia EDITOR Lana Costantini PHOTO AND COPY EDITOR Lorri Ungaretti GRapHIC DESIGNER Romney Lange PUBLIcatIONS COMMIttEE Hudson Bell Lee Bruno Lana Costantini Charles Fracchia John Freeman Chris O’Sullivan David Parry Ken Sproul Lorri Ungaretti BOARD OF DIREctORS John Briscoe, President Tom Owens, 1st Vice President Mike Fitzgerald, 2nd Vice President Kevin Pursglove, Secretary Jack Lapidos,Treasurer Rodger Birt Edith L. Piness, Ph.D. Mary Duffy Darlene Plumtree Nolte Noah Griffin Chris O’Sullivan Richard S. E. Johns David Parry Brent Johnson Christopher Patz Robyn Lipsky Ken Sproul Bruce M. Lubarsky Paul J. Su James Marchetti John Tregenza Talbot Moore Diana Whitehead Charles A. Fracchia, Founder & President Emeritus of SFHS EXECUTIVE DIREctOR Lana Costantini The Argonaut is published by the San Francisco Historical Society, P.O. Box 420470, San Francisco, CA 94142-0470. Changes of address should be sent to the above address. Or, for more information call us at 415.537.1105. TABLE OF CONTENTS A SECOND TUNNEL FOR THE SUNSET by Vincent Ring .....................................................................................................................................6 THE LAST BASTION OF SAN FRANCISCO’S CALIFORNIOS: The Mission Dolores Settlement, 1834–1848 by Hudson Bell .....................................................................................................................................22 A TENDERLOIN DISTRIct HISTORY The Pioneers of St. Ann’s Valley: 1847–1860 by Peter M. Field ..................................................................................................................................42 Cover photo: On October 21, 1928, the Sunset Tunnel opened for the first time. -

Section 3.4 Biological Resources 3.4- Biological Resources

SECTION 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4- BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section discusses the existing sensitive biological resources of the San Francisco Bay Estuary (the Estuary) that could be affected by project-related construction and locally increased levels of boating use, identifies potential impacts to those resources, and recommends mitigation strategies to reduce or eliminate those impacts. The Initial Study for this project identified potentially significant impacts on shorebirds and rafting waterbirds, marine mammals (harbor seals), and wetlands habitats and species. The potential for spread of invasive species also was identified as a possible impact. 3.4.1 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SETTING HABITATS WITHIN AND AROUND SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY The vegetation and wildlife of bayland environments varies among geographic subregions in the bay (Figure 3.4-1), and also with the predominant land uses: urban (commercial, residential, industrial/port), urban/wildland interface, rural, and agricultural. For the purposes of discussion of biological resources, the Estuary is divided into Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay (See Figure 3.4-2). The general landscape structure of the Estuary’s vegetation and habitats within the geographic scope of the WT is described below. URBAN SHORELINES Urban shorelines in the San Francisco Estuary are generally formed by artificial fill and structures armored with revetments, seawalls, rip-rap, pilings, and other structures. Waterways and embayments adjacent to urban shores are often dredged. With some important exceptions, tidal wetland vegetation and habitats adjacent to urban shores are often formed on steep slopes, and are relatively recently formed (historic infilled sediment) in narrow strips. -

Oakland Coliseum Industrial Center 5800 Coliseum Way | Oakland, CA

Premier Urban Logistics Location Oakland Coliseum Industrial Center 5800 Coliseum Way | Oakland, CA ±336,680 SF Warehouse For Lease Jason Ovadia Patrick Metzger Greg Matter Jason Cranston Robert Bisnette +1 510 285 5360 +1 510 285 5362 650 480 2220 [email protected] +1 510 661 4011 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] +1 650 480 2100 [email protected] Lic # 01742912 Lic # 01888895 Lic #01380731 Lic # 01253892 Lic # 01474433 Jones Lang LaSalle Brokerage, Inc. Real Estate License # 01856260 Unrivaled Access to Bay80 Area Urban Core 80 Vallejo Port of Benecia 80 Concord San Rafael Richmond Port of 101 Richmond 580 Walnut Creek Oakland 680 Port of Oakland Prologis Oakland Coliseum San Francisco Urban Logistics Center Port of San Francisco Oakland International Airport PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Hayward 580 Pleasanton San Francisco • Close proximity to Oakland Airport and International Airport Port of Oakland Fremont • Overweight accessible location San Mateo 880 • Great access to robust workforce 280 101 • Union Pacific Rail capabilities Driving distance Palo Alto • Heavy Power with Back Up Generator 3.5 mi Oakland International Airport 680 5.3 mi Port of Oakland San Jose • Divisible to ±168,340 SF International Airport • Available Q4 2020 16.2 mi SF Financial District San Jose 16.2 mi Port of San Francisco 27.5 mi SF International Airport 36.4 mi San Jose International Airport ±336,680 SF Current Building Configuration 80 Warehouse ±336,680 SF Office ±16,380 SF Site Size 9.93 acres Vallejo Column -

H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space

IV. Environmental Setting and Impacts H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space Environmental Setting The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department maintains more than 200 parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the City. The City’s park system also includes 15 recreation centers, nine swimming pools, five golf courses as well as tennis courts, ball diamonds, athletic fields and basketball courts. The Recreation and Park Department manages the Marina Yacht Harbor, Candlestick (Monster) Park, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Lake Merced Complex. In total, the Department currently owns and manages roughly 3,380 acres of parkland and open space. Together with other city agencies and state and federal open space properties within the city, about 6,360 acres of recreational resources (a variety of parks, walkways, landscaped areas, recreational facilities, playing fields and unmaintained open areas) serve San Francisco.172 San Franciscans also benefit from the Bay Area regional open spaces system. Regional resources include public open spaces managed by the East Bay Regional Park District in Alameda and Contra Costa counties; the National Park Service in Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties as well as state park and recreation areas throughout. In addition, thousands of acres of watershed and agricultural lands are preserved as open spaces by water and utility districts or in private ownership. The Bay Trail is a planned recreational corridor that, when complete, will encircle San Francisco and San Pablo Bays with a continuous 400-mile network of bicycling and hiking trails. It will connect the shoreline of all nine Bay Area counties, link 47 cities, and cross the major toll bridges in the region. -

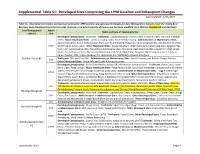

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015 Table S1. Developed sites (name and type) comprising the 1998 baseline and subsequent changes per Bear Management Subunit inside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone (Developed sites that are new, removed, or in which capacity of human-use has been modified since 1998 are highlighted and italicized). Bear Management Admin Name and type of developed sites subunit Unit Developed Campgrounds: Cave Falls. Trailheads: Coyote Meadows, Hominy Peak, S. Boone Creek, Fish Lake, Cascade Creek. Major Developed Sites: Loll Scout Camp, Idaho Youth Services Camp. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Squirrel Meadows Guard Station/Cabin, Porcupine Guard Station, Badger Creek Seismograph Site, and Squirrel Meadows CTNF GS/WY Game & Fish Cabin. Other Developed Sites: Grassy Lake Dam, Tillery Lake Dam, Indian Lake Dam, Bergman Res. Dam, Loon Lake Disperse sites, Horseshoe Lake Disperse sites, Porcupine Creek Disperse sites, Gravel Pit/Target Range, Boone Creek Disperse Sites, Tillery Lake O&G Camp, Calf Creek O&G Camp, Bergman O&G Camp, Granite Creek Cow Camp, Poacher’s TH, Indian Meadows TH, McRenolds Res. TH/Wildlife Viewing Area/Dam. Bechler/Teton #1 Trailheads: 9K1 and Cave Falls. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: South Entrance and Bechler Ranger Stations. YNP Other Developed Sites: Union Falls and Snake River picnic areas. Developed Campgrounds: Grassy Lake Road campsites (8 individual car camping sites). Trailheads: Glade Creek, Lower Berry Creek, Flagg Canyon. Major Developed Sites: Flagg Ranch (lodge, cabins and Headwater Campground with camper cabins, remote cistern and sewage treatment plant sites). Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Flagg Ranch Ranger GTNP Station, Flagg Ranch employee housing, Flagg Ranch maintenance yard. -

Historic and Conservation Districts in San Francisco

SAN FRANCISCO PRESERVATION BULLETIN NO. 10 HISTORIC AND CONSERVATION DISTRICTS IN SAN FRANCISCO HISTORIC DISTRICTS -- INTRODUCTION Over the past thirty-five years, the City and County of San Francisco has designated eleven historic districts and six conservation districts and has recognized approximately 30 districts included in the California Register of Historical Resources, the National Register of Historic Places, or named as National Historic Landmark districts. These districts encompass nationally significant areas such as Civic Center and the Presidio National Park; the City’s first commercial center in Jackson Square; warehouse districts such as the Northeast Waterfront and the South End; and residential areas such as Telegraph Hill, Liberty Hill, Alamo Square, Bush Street-Cottage Row and Webster Street. In general, an historic district is a collection of resources (buildings, structures, sites or objects) that are historically, architecturally and/or culturally significant. As an ensemble, resources in an historic district are worthy of protection because of what they collectively tell us about the past. Often, a limited number of architectural styles and types are represented because an historic district is typically developed around a central theme or period of significance. For instance, the theme for a proposed historic district might be “Late 19th century Victorian housing, designed in the Queen Anne style.” Period of significance refers to the span of time during which significant events and activities occurred within the historic district. Events and associations with historic properties are finite; most resources within an historic district have a clearly definable period of significance. A high percentage of buildings located within districts contribute to the understanding of a neighborhood’s or area’s evolution and development through integrity. -

Patrick Cunneen Collection of South End Rowing Club Photographs, 1880-2003

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8w957k3 Online items available A guide to the Patrick Cunneen collection of South End Rowing Club photographs, 1880-2003 Processed by: Amy Croft and M. Crawford, 2012. San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Phone: 415-561-7030 Fax: 415-556-3540 [email protected] URL: http://www.nps.gov/safr 2016 A guide to the Patrick Cunneen P07-004 (SAFR 23145) 1 collection of South End Rowing Club photographs, 1880-2003 A Guide to the Patrick Cunneen collection of South End Rowing Club photographs P07-004 San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, National Park Service 2016, National Park Service Title: Patrick Cunneen collection of South End Rowing Club photographs Date: 1880-2003 Date (bulk): 1930-1970 Identifier/Call Number: P07-004 (SAFR 23145) Creator: Cunneen, Patrick Physical Description: 484 items. Some items available online. Repository: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, Historic Documents Department Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Abstract: The Patrick Cunneen collection of South End Rowing Club photographs, 1880-2003, (P07-004, SAFR 23145) is comprised mainly of club members rowing, swimming, running, and socializing at their boathouse in San Francisco and in other locations in the San Francisco Bay Area. The collection has been processed to the item level. Physical Location: San Francisco Maritime NHP, Historic Documents Department Language(s): In English. Access This collection is open for use unless otherwise noted. Publication and Use Rights Some material may be copyrighted or restricted. It is the researcher's obligation to determine and satisfy copyright or other case restrictions when publishing or otherwise distributing materials found in the collections. -

Family Fun in San Francisco

Carlos Madrigal Family Fun in San Francisco San Francisco Bay Area, 4 Days Itinerary Overview 2 Daily Itineraries 3 San Francisco Bay Area Landmarks 14 San Francisco Bay Area Snapshot 14 1 things to do Itinerary Overview restaurants hotels bars, clubs & nightlife Day 1 - San Francisco Bay Area Golden Gate Park 1,000+ acres of natural wonderland in the heart of DAY NOTE: Take a Cable Car from Powell and Market streets the city all the way to Fisherman’s Wharf. Tons of good, clean, family fun can be had in the way of The Wharf’s maritime history, Strybing Arboretum & Botanical unique museums, abundant seafood, and souvenir shopping. Gardens The Wharf is also the jumping off point for visiting the notorious Nature wonderland former penitentiary on Alcatraz Island, a definite can’t-miss SF experience. Conservatory of Flowers Fancy plants Cable Cars Buca di Beppo - San Francisco San Francisco Trademark 1950s panache Fisherman's Wharf Tourist hot spot Day 4 - San Francisco Bay Area Alcatraz Island DAY NOTE: Up north, the other-worldly beauty of California Take a walk on the wild side at the legendary former redwoods adorns the walking paths of Muir Woods National prison Monument. Alternatively, you can spend hours upon hours discovering thousands of native plant and animal species on trails, in tide pools, and from ocean bluffs at Point Reyes National Day 2 - San Francisco Bay Area Seashore. Cap off your explorations with an evening of movies, games, fun shops, and a affordable gourmet food court at the DAY NOTE: The Exploratorium boasts tantalizing—and super San Francisco Metreon entertainment complex. -

February 2019 Port Commission Staff Report on the Seawall Program and Flood Study

MEMORANDUM February 12, 2019 TO: MEMBERS, PORT COMMISSION Hon. Kimberly Brandon, President Hon. Willie Adams, Vice President Hon. Gail Gilman Hon. Victor Makras Hon. Doreen Woo Ho FROM: Elaine Forbes Executive Director SUBJECT: Informational update on the San Francisco Seawall Earthquake Safety and Disaster Prevention Program (Seawall Program) DIRECTOR'S RECOMMENDATION: No action – Informational Only EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is an informational update to the Port Commission on the progress of the San Francisco Seawall Earthquake Safety and Disaster Prevention Program (Seawall Program). The last Commission update was on July 10, 2018. Highlights during this period include: • The $425 million Embarcadero Seawall Earthquake Safety General Obligation Bond Measure passed on November 6, 2018 with 82.7% yes vote. • The Port was awarded a $5M grant for the Seawall Program from the California Natural Resources Agency, included in the California 2018-19 Budget Act. • The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and Port commenced the San Francisco Waterfront Storm Risk Management Study General Investigation (GI) on September 5, 2018, and successfully completed the first study milestone, Alternatives Milestone Meeting, on December 3, 2018. • USACE and the Port came to a formal decision to suspend work on the USACE CAP 103 Study and devote resources to the larger USACE General Investigation. THIS PRINT COVERS CALENDAR ITEM NO. 13A PORT OF SAN FRANCISCO TEL 415 274 0400 TTY 415 274 0587 ADDRESS Pier 1 FAX 415 274 0528 WEB sfport.com San Francisco, CA 94111 • Field work for the geotechnical investigation was completed on time at the end of November and lab work is now under way. -

Appendix 3-‐1 Historic Resources Evaluation

Appendix 3-1 Historic Resources Evaluation HISTORIC RESOURCE EVALUATION SEAWALL LOT 337 & Pier 48 Mixed-Use Development Project San Francisco, California April 11, 2016 Prepared by San Francisco, California Historic Resource Evaluation Seawall Lot 337 & Pier 48 Mixed-Use Project, San Francisco, CA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Methods ................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Regulatory Framework ....................................................................................................... 3 IV. Property Description ................................................................................................... ….....6 V. Historical Context ....................................................................................................... ….....24 VI. Determination of Eligibility.................................................................................... ……....44 VII. Evaluation of the Project for Compliance with the Standards ............................. 45 VIII. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 58 IX. Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ 59 April 11, 2016 Historic Resource Evaluation Seawall