Ridiculing the Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

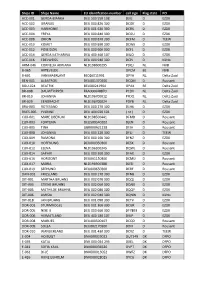

Ships ID Ships Name EU Identifcation Number Call Sign Flag State PO ACC

Ships ID Ships Name EU identifcation number call sign Flag state PO ACC-001 GERDA-BIANKA DEU 500 550 108 DJIG D EZDK ACC-002 URANUS DEU 000 820 300 DCGK D EZDK ACC-003 HARMONIE DEU 001 630 300 DCRK D EZDK ACC-004 FREYA DEU 000 840 300 DCGU D EZDK ACC-008 ORION DEU 000 870 300 DCFM D TEEW ACC-010 KOMET DEU 000 890 300 DCWK D EZDK ACC-012 POSEIDON DEU 000 900 300 DCFL D EZDK ACC-014 GERDA KATHARINA DEU 400 460 107 DIUO D EZDK ACC-016 EDELWEISS DEU 000 940 300 DCPJ D KüNo ARM-046 CORNELIA ADRIANA NLD198600295 PDQJ NL NVB B-065 ARTEVELDE OPCM BE NVB B-601 VAN MAERLANT BE026011991 OPYA NL Delta Zuid BEN-001 ALBATROS DEU001370300 DCQM D Rousant BOU-024 BEATRIX BEL000241964 OPAX BE Delta Zuid BR-008 DAUWTRIPPER FRA000648870 PCDV NL Delta Zuid BR-010 JOHANNA NLD196700012 PFDQ NL Delta Zuid BR-029 EENDRACHT NLD196700024 PDYB NL Delta Zuid BRA-003 ROTESAND DEU 000 270 300 DLHX D EZDK BUES-005 YVONNE DEU 404 020 101 ( nc ) D EZDK CUX-001 MARE LIBERUM NLD198500441 DFMD D Rousant CUX-003 FORTUNA DEU500540102 DJEN D Rousant CUX-005 TINA GBR000A21228 DFJH D Rousant CUX-008 JOHANNA DEU 000 220 300 DFLJ D TEEW CUX-009 RAMONA DEU 000 160 300 DFNZ D EZDK CUX-010 HOFFNUNG DEU000350300 DESX D Rousant CUX-012 ELENA NLD196300345 DQWL D Rousant CUX-014 SAPHIR DEU 000 360 300 DFAX D EZDK CUX-016 HORIZONT DEU001150300 DCMU D Rousant CUX-017 MARIA NLD196900388 DJED D Rousant CUX-019 SEEHUND DEU000650300 DERF D Rousant DAN-001 FRIESLAND DEU 000 170 300 DFNB D EZDK DIT-001 MARTHA BRUHNS DEU 002 070 300 DQQJ D EZDK DIT-003 STIENE BRUHNS DEU 002 060 300 DQNX D EZDK -

Developmental Therapeutics Immunotherapy

DEVELOPMENTAL THERAPEUTICS—IMMUNOTHERAPY 2500 Oral Abstract Session Clinical activity of systemic VSV-IFNb-NIS oncolytic virotherapy in patients with relapsed refractory T-cell lymphoma. Joselle Cook, Kah Whye Peng, Susan Michelle Geyer, Brenda F. Ginos, Amylou C. Dueck, Nandakumar Packiriswamy, Lianwen Zhang, Beth Brunton, Baskar Balakrishnan, Thomas E. Witzig, Stephen M Broski, Mrinal Patnaik, Francis Buadi, Angela Dispenzieri, Morie A. Gertz, Leif P. Bergsagel, S. Vincent Rajkumar, Shaji Kumar, Stephen J. Russell, Martha Lacy; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, Roches- ter, MN; Vyriad and Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN Background: Oncolytic virotherapy is a novel immunomodulatory therapeutic approach for relapsed re- fractory hematologic malignancies. The Indiana strain of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus was engineered to encode interferon beta (IFNb) and sodium iodine symporter (NIS) to produce VSV-IFNb-NIS. Virally en- coded IFNb serves as an index of viral proliferation and enhances host anti-tumor immunity. NIS was in- serted to noninvasively assess viral biodistribution using SPECT/PET imaging. We present the results of the phase 1 clinical trial NCT03017820 of systemic administration of VSV-IFNb-NIS among patients (pts) with relapsed refractory Multiple Myeloma (MM), T cell Lymphoma (TCL) and Acute myeloid Leu- 9 kemia (AML). Methods: VSV-IFNb-NIS was administered at 5x10 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infec- 11 tious dose) dose level 1 to dose level 4, 1.7x10 TCID50. The primary objective was to determine the maximum tolerated dose of VSV-IFNb-NIS as a single agent. Secondary objectives were determination of safety profile and preliminary efficacy of VSV-IFNb-NIS. -

Programme Book

10th European Public Health Conference OVERVIEW PROGRAMME Sustaining resilient WEDNESDAY 1 NOVEMBER THURSDAY 2 NOVEMBER FRIDAY 3 NOVEMBER SATURDAY 4 NOVEMBER 09:00 – 12:30 09:00 – 10:30 08:30 - 09:30 08:30 - 10:00 Pre-conferences Parallel sessions 1 Parallel sessions 4 Parallel session 8 09:40 - 10:40 10:10 - 11:10 and healthy communities Plenary 3 Parallel session 9 10:30 – 11:00 10:30 – 11:00 10:40 – 11:10 11:10 – 11:40 Coffee/tea Coffee/tea Coffee/tea Coffee/tea 11th European Public Health Conference 2018 12th European Public Health Conference 2019 11:00 – 12:00 11:10 - 12:10 11:40 - 13:10 Ljubljana, Slovenia Marseille, France PROGRAMME Plenary 1 Parallel sessions 5 Parallel session 10 12:30 – 13:30 12:00 – 13:15 12:10 – 13:40 13:10 – 14:10 Lunch for pre-conference Lunch – Lunch symposiums and Lunch – Lunch symposiums Lunch – Join the Networks delegates only Join the Networks and Join the Networks 13:30 – 17:00 13:15 - 14:15 13:40 - 14:40 14:10 - 15:10 Pre-conferences Plenary 2 Plenary 4 Plenary 5 14:25 – 15:25 14:50-15:50 15:10 – 16:00 Parallel sessions 2 Parallel sessions 6 Closing Ceremony Winds of Change: towards new ways Building bridges for solidarity 15:00 – 15:30 15:25 – 15:55 15:50 – 16:20 of improving public health in Europe and public health Coffee/tea Coffee/tea Coffee/tea 17:00 16:05 – 17:05 16:20 - 17:50 28 November - 1 December 2018 20 - 23 November 2019 End of Programme Parallel sessions 3 Parallel sessions 7 Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana Marseille Chanot, Marseille 17:15 - 18:00 Opening Ceremony @EPHConference #EPH2018 -

The University of Chicago Homo-Eudaimonicus

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO HOMO-EUDAIMONICUS: AFFECTS, BIOPOWER, AND PRACTICAL REASON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY COMMITTEE ON THE CONCEPTUAL AND HISTORICAL STUDIES OF SCIENCE AND DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY FRANCIS ALAN MCKAY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Francis Mckay All Rights Reserved If I want to be in the world effectively, and have being in the world as my art, then I need to practice the fundamental skills of being in the world. That’s the fundamental skill of mindfulness. People in general are trained to a greater or lesser degree through other practices and activities to be in the world. But mindfulness practice trains it specifically. And our quality of life is greatly enhanced when we have this basic skill. — Liam Mindfulness is a term for white, middle-class values — Gladys Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ viii Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... x Chapter 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1: A Science and Politics of Happiness .............................................................................. 1 1.2: Global Well-Being ........................................................................................................ -

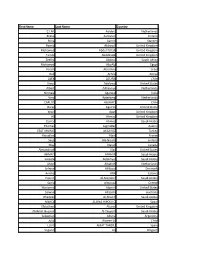

First Name Last Name Country C.I.M. Aalders Netherlands Riikka

First Name Last Name Country C.I.M. Aalders Netherlands Riikka Aaltonen Finland Riina Aarnio Sweden Hamid Abboudi United Kingdom Mohamed Abdel-fattah United Kingdom Tamer Abdelrazik United Kingdom Zeelha Abdool South Africa Mohamed AboAly Egypt Yoram Abramov Israel Bob Achila Kenya ALEX ACUÑA Chile Amos Adelowo United States Albert Adriaanse Netherlands Nirmala Agarwal India Vera Agterberg Netherlands CARLOS AGUAYO Chile Oscar Aguirre United States Wael Agur United Kingdom Ali Ahmad United Kingdom Gamal Ahmed Saudi Arabia Thomas Aigmüller Austria ESAT MURAT AKCAYOZ Turkey Riouallon Alain France Seija Ala-Nissilä Finland May Alarab Canada Alexandriah Alas United States AHMED ALBADR Saudi Arabia Lateefa Aldakhyel Saudi Arabia Akeel Alhafidh Netherlands Selwan Al-Kozai Denmark Annika Allik Estonia Hazem Al-Mandeel Saudi Arabia Sania Almousa Greece Marianna Alperin United States Salwan Al-Salihi Australia Ghadeer Al-Shaikh Saudi Arabia MERCE ALSINA HIPOLITO Spain Efstathios Altanis United Kingdom Abdulah Hussein Al-Tayyem Saudi Arabia Sebastian Altuna Argentina Julio Alvarez U. Chile LLUIS AMAT TARDIU Spain Segaert An Belgium Lea Laird Andersen Denmark Vasanth Andrews United Kingdom Beata Antosiak Poland Vanessa Apfel Brazil Catherine Appleby United Kingdom Rogério Araujo Brazil CARLOS ALFONSO ARAUJO ZEMBORAIN Argentina Rajka Argirovic Serbia Edwin Arnold New Zealand Christina Arocker Austria Juan Carlos Arone Chile Makiya Ashraf United Kingdom Kari Askestad Norway R Phil Assassa United Kingdom LESTER ASTUDILLO Chile Leyla Atay Denmark STAVROS -

Societal Discourses on the Sexual Abuse of Children and Their Influence on the Catholic Church

IAPT – 01/2019 typoscript [AK] – 05.03.2019 – Seite 20 – 2. SL The politics of meaning: societal discourses on the sexual abuse of children and their influence on the Catholic Church Karlijn Demasure This chapter on child sexual abuse contributes to an understanding of the shift from a focus on perpetrators that denies the voice of the victims, even holding the victims to be sexual delin- quents responsible for their abuse, to a “victims first” approach. The Catholic Church has been heavily influenced by the major discourses in society that give power to psychiatrists, therapists and social workers. However, with regard to clerical sexual abuse in the Church, two distinct discourses can be identified. In the first, sin is considered a cause for abuse, reducing it to a mat- ter of the will. The second discourse restricts child sexual abuse to the North American context, suggesting that moral decay has contaminated the clergy in that region. Introduction Prof. Dr. Karlijn Demasure is the former Executive Direc- tor of the Center for Child Protection at the Pontifical In recent decades, sexual abuse has been widely dis- Gregorian University in Rome. cussed in the Catholic Church as well as in society at Before, she acted as the Dean of the Faculty of Philoso- large. Also, dominant discourses in society were phy (2011–2014), and of Human Sciences (2010–2014) at previously more concerned about the perpetrators Saint Paul University, Ottawa, Canada. She there held than the victims. But recently, a major paradigm the Sisters-of-Our-Lady-of-the-Cross Research Chair in Christian Family Studies (2008–2014). -

Repertoire Karlijn Nijkamp

Repertoire Karlijn Nijkamp Repertoire Karlijn Nijkamp Nummer - ArtiestToonsoort 7 nation army - The White Stripes All of me - John Legend All the small things - Blink 182 Angels - Robbie Williams Angie - The Rolling Stones Are you gonna be my girl - Jet Are you kidding me - Anouk Bad moon rising - CCR Bad reputation - Joan Jett Behind blue eyes - The Who Believe - Cher Best of you - Foo Fighters Big black horse & a cherry tree - KT Tunstall Billy Jean - Michael Jackson Bitch - Meredith Brooks Born to be wild - Steppenwolf Bring me some water - Melissa Etheridge Cake by the ocean - DNCE Child in time - Deep Purple Christmas time - Bryan Adams Colors of the wind - Vanessa Williams Country roads - John Denver Crazy little thing called love Creep - Radiohead Dear mr. President - Pink Dreams - Fleetwood Mac Driving home for christmas - Chris Rea Fever - Peggy Lee Fly away -Lenny Kravitz Hallelujah - Leonard Cohen Hand in my pocket - Alanis Morissette Het is een nacht - Guus Meeuwis Het regent zonnenstralen - Acda & de Munnik Highway to hell - ACDC Hit the road jack - Ray Charles Hotel california - The Eagles Hound dog - Elvis Presley House of the rising sun - Animals I alone - Live I kissed a girl - Katy Perry I love rock 'n' roll I would stay - Krezip I'm not so tough - Ilse de lange I'm yours - Jason Mraz Iedereen is van de wereld - The Scene Iris - Goo Goo Dolls Ironic - Alanis Morissette It's raining men - The Weather Girls Jingle bell rock - Bobby Helms Jolene - Dolly Parton Just like a pill - Pink Just the way you are - Bruno mars Kiss -

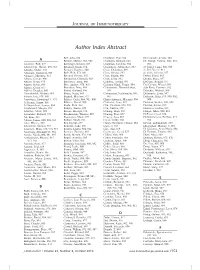

Download Abstract Index

JOURNAL OF IMMUNOTHERAPY Author Index Abstract Bell, John, 898 Chadwick, Eric, 912 De Coninck, Arlette, 880 A Bellone, Matteo, 881, 902 Champlin, Richard, 863 De Giorgi, Valeria, 860, 885, Aarntzen, Erik, 877 Benninger, Kristen, 887 Chapman, Caroline, 904 891 Abate-Daga, Daniel, 859, 867 Bensmail, Ilham, 874 Chaudhury, Abhik Ray, 887 de Gruijl, Tanja, 880, 918 Abdalla, Maher, 873 Benteyn, Daphne´ , 880 Chen, Chuanben, 892 de Pril, Veerle, 913 Abraham, Roshini S, 869 Berk, Erik, 874, 884 Chen, George, 892 de Vries, Jolanda, 877 Adamow, Matthew, 913 Bernard, Dannie, 892 Chen, Jingou, 860 Debay, Drew, 883 Adams, George, 900 Bernatchez, Chantale, 863 Chen, Lisha, 892 Decker, Stacy, 897 Adams, Sarah, 878 Bershteyn, Anna, 866 Chhabra, Arvind, 893 DeConti, Ronald, 877 Adams, Sylvia, 889 Best, Andrew, 878, 918 Chiarion Sileni, Vanna, 894 Del Campo, Miguel, 891 Adema, Gosse, 877 Bhardwaj, Nina, 889 Chinnasamy, Dhanalakshmi, dela Rosa, Corazon, 912 Adkins, Douglas, 890 Bhatti, Shahzad, 896 861 Delacher, Michael, 900 Ahmadzadeh, Mojgan, 863 Bhave, Neela, 885 Chinnasamy, Nachimuthu, 860, Delamarre, Louis, 897 Ahrens, Eric, 878, 880 Biagioli, Matthew, 877 867 Delcayre, Alain, 879, 900, 902, Akporiaye, Emmanuel T, 873 Bifulco, Carlo, 864, 905, 908 Chiriva-Internati, Maurizio, 904 908 Al Homsi, Samer, 861 Bilhartz, David, 900 Chisholm, Lana, 912 Demaria, Sandra, 888, 889 Al-Shamkhani, Aymen, 894 Binda, Elisa, 864 Chu, Christina, 878, 918 Demian, Soheir, 895 Alaghmand, Marjan, 874 Binkley, Elaine, 872 Chu, Xuezhe, 892 Denisova, Galina, 866 Albertini, -

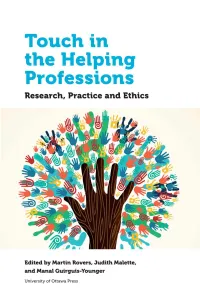

Touch in the Helping Professions

TOUCH IN THE HELPING PROFESSIONS Touch in the Helping Professions.indd 1 18-03-06 11:00 Page left blank intentionally Touch in the Helping Professions.indd 2 18-03-06 11:00 TOUCH IN THE HELPING PROFESSIONS Research, Practice and Ethics EDITED BY Martin Rovers, Judith Malette and Manal Guirguis-Younger University of Ottawa Press 2017 Touch in the Helping Professions.indd 3 18-03-06 11:00 The University of Ottawa Press gratefully acknowledges the support extended to its publishing list by Canadian Heritage through the Canada Book Fund, by the Canada Council for the Arts, by the Ontario Arts Council, by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, and by the University of Ottawa. Copy editing: Michael Waldin Proofreading: Thierry Black Typesetting: Édiscript enr. Cover design: Édiscript enr. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Touch in the helping professions: research, practice, and ethics / edited by Martin Rovers, Judith Malette and Manal Guirguis-Younger. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-7766-2755-7 (softcover). ISBN 978-0-7766-2756-4 (PDF). ISBN 978-0-7766-2757-1 (EPUB) ISBN 978-0-7766-2758-8 (Kindle) 1. Touch—Therapeutic use. I. Rovers, Martin, 1949-, editor II. Malette, Judith, 1963-, editor III. Guirguis-Younger, Manal, 1967-, editor IV. Title. V. Title. RC489.T69T54 2018 615.8’22 C2018-901015-0 C2018-901016-9 The use of the term “therapeutic touch” used in this book refers to touch within a psychotherapeutic relationship and does not refer to the registered intellectual property of Therapeutic Touch® which is a therapeutic practice and modality used in clinical practice that does not necessarily require physical touch. -

Name Clustering on the Basis of Parental Preferences Gerrit Bloothooft and Loek Groot Utrecht University, the Netherlands

names, Vol. 56, No. 3, September, 2008, 111–163 Name Clustering on the Basis of Parental Preferences Gerrit Bloothooft and Loek Groot Utrecht University, The Netherlands Parents do not choose fi rst names for their children at random. Using two large datasets, for the UK and the Netherlands, covering the names of children born in the same family over a period of two decades, this paper seeks to identify clusters of names entirely inferred from common parental naming preferences. These name groups can be considered as coherent sets of names that have a high probability to be found in the same family. Operational measures for the statistical association between names and clusters are developed, as well as a two-stage clustering technique. The name groups are subsequently merged into a limited set of grand clusters. The results show that clusters emerge with cultural, linguistic, or ethnic parental backgrounds, but also along characteristics inherent in names, such as clusters of names after fl owers and gems for girls, abbreviated names for boys, or names ending in –y or -ie. Introduction The variety in personal given names has increased enormously over the past century. In the Netherlands, the top 3, top 10, and top 100 names account, respectively, for 16%, 33%, and 70% of the fi rst names of elderly born between 1910 and 1930, while these fi gures are 3%, 8%, and 39% for babies born between 2000 and 2004. Compa- rable fi gures are presented by Galbi (2002, 4) for England and Wales. Along with the increase in the variety in names, the motives behind the choice of names for children by their parents have changed from a more or less prescribed naming after relatives to a free decision, a process that was facilitated in the Netherlands by the tolerant name law of 1970. -

Doing Business in the European Union 2021: Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands

AUSTRIA Doing Business in the European Union 2021: Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands Comparing Business Regulation for Domestic Firms in 24 Cities in Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands with Other European Union Member States with funding by the European Union © 2021 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The sole responsibility of this publication lies with the author. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. All maps in this report were cleared by the Cartography Unit of the World Bank Group. The European Union is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

INVESTIGATION INTO the EFFECTS of PLAYING POSTURE on FATIGUE in VIOLINISTS and VIOLISTS by Ethan Thomas Triplett Honors Thesis A

! "#$%&'"()'"*#!"#'*!'+%!%,,%-'&!*,!./)0"#(!.*&'12%!*#!,)'"(1%!"#! $"*/"#"&'&!)#3!$"*/"&'&! ! 45! %6789!'7:;8<!'=>?@A66! ! +:9:=<!'7A<><! )??8@8B7>89!&686A!19>CA=<>65!! &D4;>66AE!6:!67A!3A?8=6;A96!:F!+A8@67!89E!%GA=B><A!&B>A9BA! 89E!'7A!+:9:=<!-:@@AHA! >9!?8=6>8@!FD@F>@@;A96!:F!67A!=AID>=A;A96<!F:=!67A!EAH=AA!:F!! J8B7A@:=!:F!&B>A9BA! K85L!MNMO! ! ! ! ! PPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPP! +A=;89!C89!QA=R7:CA9L!.7S3SL!'7A<><!3>=AB6:=! ! ! PPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPP! %=>B!T::96UL!3K)L!&AB:9E!2A8EA=! ! ! PPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPP! +A=;89!C89!QA=R7:CA9L!.7S3SL!3A?8=6;A968@!+:9:=<!3>=AB6:=! ! ! PPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPP! VAFF:=E!$87@4D<B7L!.7S3SL!3A89L!'7A!+:9:=<!-:@@AHA! ! !"#$%&!'(&!)"*!"&)*&+$*$,,$-&*),*./(0!"'*.)%&12$*)"*,(&!'1$*!"*#!)/!"!%&%*("3*#!)/!%&%* "#$%&'(%! ! .@85>9H!8!;D<>B8@!>9<6=D;A96!><!8!B:;;:9!?8<6>;A!8=:D9E!67A!W:=@E!89E!F:=!<:;AL!>6! ><!8!B8=AA=!89E!7:W!67A5!;8RA!67A>=!@>C>9HS!KD<>B>89<X!4:E>A<!8=A!?D6!D9EA=!B:9<6896!<6=A<<! F=:;!?@85>9H!89!>9<6=D;A96S!&686><6>B<!78CA!<DHHA<6AE!6786!D?W8=E<!:F!YNZ!:F!?=:FA<<>:98@! ;D<>B>89<!<DFFA=!F=:;!8!?A=F:=;89BA[=A@86AE!;D<BD@:<RA@A68@!E><:=EA=!\.2K3<]!6786!B89!@A8E! 6:!67A!>984>@>65!6:!?@85!67A!>9<6=D;A96!F:=!8!?A=>:E!:F!6>;A!89E!67A=AF:=A!8FFAB6!67A>=!84>@>65!6:! W:=RS!KD<>B>89<!8=A!4A>9H!E>8H9:<AE!W>67!.2K3<!86!A8=@>A=!8HA<L!A<?AB>8@@5!67:<A!>9!<B7::@<! F:=!;D<>BS!$>:@>9><6<!89E!C>:@><6<!F:=;!:9A!:F!67A!H=:D?<!6786!><!;:<6!@>RA@5!6:!AG?A=>A9BA!8! .2K3S! K:<6! =A<A8=B7! 78<! B:9B@DEAE! 6786!