The University of Chicago Homo-Eudaimonicus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happiness Syllabus 3-28-09

The Pursuit of Happiness Political Science 192 SSB 353 Darren Schreiber Spring 2009 Social Science Building 367 (858) 534-1854 [email protected] Class Meets: Monday 2:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m. on April 6 & 20, May 4 & 18, June 1 Office Hours: Thursday, 2:00 – 3:00 p.m. My Mission as a Teacher: “To enable my students to learn joyfully, think clearly, read carefully, and write well.” Abstract The Declaration of Independence describes the pursuit of happiness as an inalienable right. Economists are investigating subjective well-being. And, positive psychology is providing new insights. How might political science contribute to our individual and collective pursuit of happiness? Books Required: Jonathan Haidt (2006) The Happiness Hypothesis ($10.85) Recommended: Martin Seligman (2005) Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment ($10.20) Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1998) Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life ($10.17) Topics & Readings Meeting 1 (Monday, April 6th) – Introduction (Book Group 1/Articles Group 5) Alexander Weiss (2008) “Happiness Is a Personal(ity) Thing: The Genetics of Personality and Well-Being in a Representative Sample” Psychological Science (6 pages) Christopher K. Hsee and Reid Hastie (2006) Decision and experience: why don’t we choose what makes us happy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences (7 pages) Carol Graham (2005) “The Economics of Happiness: Insights on globalization from a novel approach” World Economics (15 pages) Haidt The Happiness Hypothesis -

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Leadership, Followership, and Evolution Some Lessons from the Past

Leadership, Followership, and Evolution Some Lessons From the Past Mark Van Vugt University of Kent Robert Hogan Hogan Assessment Systems Robert B. Kaiser Kaplan DeVries Inc. This article analyzes the topic of leadership from an evo- Second, the literature focuses on leaders and tends to lutionary perspective and proposes three conclusions that ignore the essential role of followers (Hollander, 1992; are not part of mainstream theory. First, leading and Yukl, 2006). Third, research largely concentrates on prox- following are strategies that evolved for solving social imate issues of leadership (e.g., What makes one person a coordination problems in ancestral environments, includ- better leader than others?) and rarely considers its ultimate ing in particular the problems of group movement, intra- functions (e.g., How did leadership promote survival and group peacekeeping, and intergroup competition. Second, reproductive success among our ancestors?) (R. Hogan & the relationship between leaders and followers is inher- Kaiser, 2005). Finally, there has been little cross-fertiliza- ently ambivalent because of the potential for exploitation of tion between psychology and disciplines such as anthro- followers by leaders. Third, modern organizational struc- pology, economics, neuroscience, biology, and zoology, tures are sometimes inconsistent with aspects of our which also contain important insights about leadership evolved leadership psychology, which might explain the (Bennis, 2007; Van Vugt, 2006). alienation and frustration of many citizens and employees. This article offers a view of leadership inspired by The authors draw several implications of this evolutionary evolutionary theory, which modern scholars increasingly analysis for leadership theory, research, and practice. see as essential for understanding social life (Buss, 2005; Lawrence & Nohria, 2002; McAdams & Pals, 2006; Nettle, Keywords: evolution, leadership, followership, game the- 2006; Schaller, Simpson, & Kenrick, 2006). -

Work, Wisdom, and Happiness BSPA-GB 3110.30 Mondays 6-9 Pm Beginning 2/11/19, Room Tba BELOW IS the SYLLABUS from 2018

Work, Wisdom, and Happiness BSPA-GB 3110.30 Mondays 6-9 pm beginning 2/11/19, room tba BELOW IS THE SYLLABUS FROM 2018. THE SPRING 2019 COURSE WILL BE SIMILAR. THE MAIN READING IS CAROLINE WEBB’S BOOK Professor: Jonathan Haidt, [email protected], Office hours: Mondays after class; Thursdays 4-6 in KMC 7-98 Course Overview: For centuries, work was regarded as nothing but toil— a requirement for earning one's daily bread. But in recent decades, expectations about work have been transformed, as has its very nature. While it still provides one’s daily bread, it is also regarded as a major opportunity for people to find purpose, meaning, and happiness in their lives. In this course we'll study the latest research on what makes people happy at work, on how happiness at work improves the quality of work, and on what makes a career not just successful but meaningful. We will also discuss some of the impediments—both individual and organizational—to doing meaningful and satisfying work. Students will develop their own visions of their ideal career, and of the ideal company they’d like to lead or work for. They will also begin making changes to their daily lives, to improve their chances of success and happiness. Course Requirements: 1) 35% of the grade will be based on your class participation, which is not just the quantity of your comments but the nature of your engagement with the class. 2) 20% will be based on 4 one-page integration papers that you’ll submit by 10 am on the day of each class. -

The Happiness Advantage

THE HAPPINESS ADVANTAGE TODAY YOU’RE GONNA… Directly experience a variety of methods for increasing happiness. YAY! Identify a variety of activities that support your happiness Create a personal plan for incorporating more happy-making activities into your life. HEY, LET’S WATCH THIS VIDEO… “The Happiness Advantage: Research linking happiness and success” - Shawn Achor http://www.ted.com/talks/shawn_achor_the_happy_secret_to_better_work.html KEY POINTS AND INSIGHTS FROM VIDEO The public library is the center of public happiness first, of public education, next. John Cotton Dana ULA Youth Services Round Table Fall Workshop | September 18, 2015 | (CC BY-SA 3.0 US) Peter Bromberg | peterbromberg.com 3 gratitudes 2 Each day, write three things for which you are grateful. September 18 happiness advantage happiness 1. 2. 3. September 19 1. 2. 3. September 20 1. 2. 3. September 21 1. Happiness is not a goal...it's a by-product 2. of a life well lived. 3. Eleanor Roosevelt September 22 1. 2. 3. ULA Youth Services Round Table Fall Workshop | September 18, 2015 | (CC BY-SA 3.0 US) Peter Bromberg | peterbromberg.com ingredients for happiness 3 Write down one positive experience from the last 24 hours advantage happiness Write down three things that inspire a feeling of gratitude. Exercise 3-5 Minutes Meditate/Pray/Mindful Breathing Perform an act of kindness or express appreciation to someone The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts. S t r e t c h Marcus Aurelius Pet a pet (a furry pet!) or hug or cuddle with a friend or loved one Spend time with someone you feel good around (“resonant relationship”) Let us be grateful to the people who make us happy; they are the charming Dealer’s Choice: What else facilitates your happiness? gardeners who make our souls blossom. -

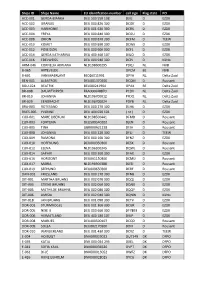

Ships ID Ships Name EU Identifcation Number Call Sign Flag State PO ACC

Ships ID Ships Name EU identifcation number call sign Flag state PO ACC-001 GERDA-BIANKA DEU 500 550 108 DJIG D EZDK ACC-002 URANUS DEU 000 820 300 DCGK D EZDK ACC-003 HARMONIE DEU 001 630 300 DCRK D EZDK ACC-004 FREYA DEU 000 840 300 DCGU D EZDK ACC-008 ORION DEU 000 870 300 DCFM D TEEW ACC-010 KOMET DEU 000 890 300 DCWK D EZDK ACC-012 POSEIDON DEU 000 900 300 DCFL D EZDK ACC-014 GERDA KATHARINA DEU 400 460 107 DIUO D EZDK ACC-016 EDELWEISS DEU 000 940 300 DCPJ D KüNo ARM-046 CORNELIA ADRIANA NLD198600295 PDQJ NL NVB B-065 ARTEVELDE OPCM BE NVB B-601 VAN MAERLANT BE026011991 OPYA NL Delta Zuid BEN-001 ALBATROS DEU001370300 DCQM D Rousant BOU-024 BEATRIX BEL000241964 OPAX BE Delta Zuid BR-008 DAUWTRIPPER FRA000648870 PCDV NL Delta Zuid BR-010 JOHANNA NLD196700012 PFDQ NL Delta Zuid BR-029 EENDRACHT NLD196700024 PDYB NL Delta Zuid BRA-003 ROTESAND DEU 000 270 300 DLHX D EZDK BUES-005 YVONNE DEU 404 020 101 ( nc ) D EZDK CUX-001 MARE LIBERUM NLD198500441 DFMD D Rousant CUX-003 FORTUNA DEU500540102 DJEN D Rousant CUX-005 TINA GBR000A21228 DFJH D Rousant CUX-008 JOHANNA DEU 000 220 300 DFLJ D TEEW CUX-009 RAMONA DEU 000 160 300 DFNZ D EZDK CUX-010 HOFFNUNG DEU000350300 DESX D Rousant CUX-012 ELENA NLD196300345 DQWL D Rousant CUX-014 SAPHIR DEU 000 360 300 DFAX D EZDK CUX-016 HORIZONT DEU001150300 DCMU D Rousant CUX-017 MARIA NLD196900388 DJED D Rousant CUX-019 SEEHUND DEU000650300 DERF D Rousant DAN-001 FRIESLAND DEU 000 170 300 DFNB D EZDK DIT-001 MARTHA BRUHNS DEU 002 070 300 DQQJ D EZDK DIT-003 STIENE BRUHNS DEU 002 060 300 DQNX D EZDK -

Humanum Review Humanum Issues in Family, Culture & Science

3/5/2020 Searching for Happiness On an Elephant's Back | Humanum Review Humanum Issues in Family, Culture & Science Issue 4 Searching for Happiness On an Elephant's Back COLET C. BOSTICK Haidt, Jonathan, The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom (Basic Books, 2006). In the beginning of The Everlasting Man, G.K. Chesterton proposes that “there are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place.” At the end of The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, Jonathan Haidt concludes that “we can choose directions in life that will lead to satisfaction, happiness, and a sense of meaning [but] we can’t simply select a destination and walk there directly.” The juxtaposition of these two images of the search for happiness as a journey lays bare a fundamental question for reflective people in the 21st century: If it’s “not the destination, but the journey” that gives one a sense of purpose, does one need a destination at all? Chesterton and the Western Tradition assert that life’s journey is a quest, but, for moderns like Haidt, life is at best a walkabout in the wilderness. Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist specializing in the field of positive psychology, the study of behaviors and conditions that lead to human flourishing. The Happiness Hypothesis was written in 2006, while Haidt was a professor at the University of Virginia trying to compress the entire discipline of psychology into a four-month semester. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India

High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India Instituted by the Planning Commission of India PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor High Level Expert Group Reporton Universal Health Coverage for India Instituted by Planning Commission of India Submitted to the Planning Commission of India New Delhi October, 2011 PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor DEDICATION "This report is dedicated to the people of India whose health is our most precious asset and whose care ¡s our most sacred duty" PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Contents PREFACE 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 VOLUME 1 53 Chapter 1: VisionforUniversalHealthCoveragefor India. 53 Chapter2 : HealthFinancingandFinancialProtection 67 Chapter3 : AccesstoMedicines ,Vaccines &Technology 92 AnnexuretoChapterl : UniversalHealthCareSystems Worldwide: SixteeninternationalCaseStudies . 114 VOLUME 2 153 Chapter4: Human Resources for Health 153 Chapter5:Health Service Norms 189 VOLUME 3 241 Chapter6: Management and Institutional Reforms. 241 Chapter7: Community Participation and Citizen Engagement 271 Chapter 8: Social Determinants of Health . 291 Chapter 9: Gender and Health 311 PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor PROCESS OF CONSULTATIONS 318 COMPOSiTION OF HIGH LEVEL EXPERT GROUP . 335 EXPERT CONSULTATIONS & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 336 ABBREVIATIONS. 339 COMPOSiTION OF HLEG SECRETARIAT 344 PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Preface The High Level Expert Group (HLEG) on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) was constituted by the Planning Commission of India in October 2010, with the mandate of developing a framework for providing easily accessible and affordable health care to all Indians. -

WWS 302/ ECO 359 - International Development Fall 2015 Semester

WWS 302/ ECO 359 - International Development Fall 2015 Semester Classes: M/W 10-10:50, Robertson 016 Precept: Times TBA Instructor: Alicia Adsera Office hours M 2:30-4, 347 Wallace Hall or by appointment [email protected] TA: Federico Huneeus [email protected] Office hours TBA Course Description The course will focus on less developed countries and will consider topics such as economic growth and personal well-being; economic inequality and poverty; intra-household resource allocation and gender inequality; fertility and population change, credit markets and microfinance; labor markets and trade policy. It will tackle these issues both theoretically and empirically. Please do not feel overwhelmed with the length of the syllabus. The reading list contains a few required papers and then a bunch of additional recommended papers for those of you who are interested in a particular subject. I will discuss some of the results in those papers but you do not need to read them. Also some of the required papers may contain some statistical analysis beyond the knowledge of many of you. I am completely aware of that. I only expect you to understand the ideas and main results exposed in the paper. I will discuss them with you in class & precepts. Assignments The basic textbook for the class is Development Economics by Debraj Ray (Princeton University Press 1998). Many readings come from: Gerald Meier and James E. Rauch (eds.) Leading Issues in Economic Development, Oxford University Press, 2005 (8th Edition). Around 50-100 pages of reading per week are expected. The assignments include a midterm exam, four problem sets/short essay questions and a final exam. -

Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights

Portland State University PDXScholar Book Publishing Final Research Paper English 5-2017 Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights Gloria H. Mulvihill Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Publishing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mulvihill, Gloria H., "Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights" (2017). Book Publishing Final Research Paper. 26. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper/26 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Publishing Final Research Paper by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Mulvihill 1 Trends in Marketing for Books on Animal Rights Gloria H. Mulvihill MA in Book Publishing Thesis Spring 2017 Mulvihill 2 Abstract Though many of us have heard the mantra that we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, marketers in book publishing bank on the fact that people do and will continue to buy and read books based not only on content, but its aesthetic appeal. This essay will examine the top four marketing trends that can be observed on the Amazon listings for books published on animal rights within the last ten years, specifically relating to titles, cover design, and the intended audience. From graphic adaptations of animals to traditional textbook approaches and animal photography, publishers are striving to evoke interest and investment in literature concerning a politically charged and inherently personal topic. -

The Brain of Buddha

(consciousness redux) The Brain of Buddha An encounter with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the scientific study of meditation BY CHRISTOF KOCH ) Knowledge can be communicat- tic community living in exile in India His Holiness the Dalai Lama listens to the author talking about the brain basis of con- ed, but not wisdom. One can find with modern science. About a dozen of meeting sciousness during a six-day encounter be- ( it, live it, do wonders through it, us—physicists, psychologists, brain sci- tween Tibetan Buddhism and science. but one cannot communicate and entists and clinicians, leavened by a teach it. French philosopher—introduced quan- INSTITUTE tum mechanics, neuroscience, con- circle—such as from his translator, Ti- IFE L THIS LINE FROM Herman Hesse’s 1922 sciousness and various clinical aspects of betan Jinpa Thupten, who has a doctor- ); AND novel Siddhartha came unbidden to me meditative practices to a few thousand ate in philosophy from the University of Koch during a recent weeklong visit to Dre- Buddhist monks and nuns. As we lec- Cambridge, and from the French monk MIND pung Monastery in southern India. His tured, we were quizzed, probed and gen- Matthieu Ricard, who holds a Ph.D. in Holiness the Dalai Lama had invited the tly made fun of by His Holiness, who sat molecular biology from the Pasteur Insti- U.S.-based Mind and Life Institute to beside us [see photograph above]. We tute in Paris—as they and their brethren HRISTOF KOCH ( KOCH HRISTOF OURTESY OF familiarize the Tibetan Buddhist monas- learned as much from him and his inner from us.