Touch in the Helping Professions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reiki Energy Medicine: Enhancing the Healing Process by Alice Moore, RN, BS, Reiki Master Hartford Hospital Dept.Of Integrative Medicine, Hartford, CT

Reiki Energy Medicine: Enhancing the Healing Process by Alice Moore, RN, BS, Reiki Master Hartford Hospital Dept.of Integrative Medicine, Hartford, CT With increasing frequency and confidence, we speak of Energy Medicine (also known as “energy work”) as if it was a new form of therapy for our patients’ ailments. Not so. Thousands of years ago ancient cultures understood intuitively what scientific research and practitioners world-wide are confirming today about the flow (or lack of flow) of energy in the body and, how the use of energy therapies can enhance the healing process. As well known medical surveys report approximately 50% of the American public using some form of complementary or alternative therapy, “energy work” is among the ten most frequently used. Research has shown that these therapies (often called “mind-body-spirit techniques”) can help decrease anxiety, diminish pain, strengthen the immune system, and accelerate healing, whether by simply inducing the “relaxation response” (and reversing the “stress response” and subsequent impacts on the body, illness, and disease) or, by more complex mechanisms. When patients choose these options, there is often a greater sense of participation in healing and restoration of health and, patient satisfaction is often increased in the process. It was with this understanding that Women’s Health Services at Hartford Hospital (in collaboration with Alice Moore, RN, BS, Reiki Master and Volunteer Services) began to integrate Reiki healing touch (one of the most well known forms of “energy work” ) on the inpatient gynecological surgical unit in 1997. Patients have been very pleased to be offered an option that is so relaxing and helps decrease their anxiety as well as their discomfort. -

An Investigation Into How the Meanings of Spirituality Develop Among Accredited Counsellors When Practicing a New Shamanic Energy Therapy Technique

An investigation into how the meanings of spirituality develop among accredited counsellors when practicing a new shamanic energy therapy technique. Karen Ward B.Sc (Hons), MA Thesis submitted for the award of PhD School of Nursing and Human Sciences Dublin City University Supervisors: Dr Liam MacGabhann, School of Nursing and Human Sciences, DCU, Dr Ger Moane, University College Dublin January 2019 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: _________________________ (Candidate): ID No: 14113881 Date: 13th December 2018 ii Table of Contents Declaration ii List of figures iii Abstract iv Acknowledgements v CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 12 1.1 Background 12 1.1.1 Counselling evolving to include the psycho-spiritual 12 1.1.2 Spirituality in healthcare 13 1.1.3 Interest in spiritual tools within counselling 16 1.1.4 Development of secular sacred self-healing tools 18 1.2 Spirituality in a contemporary Irish context 21 1.2.1 Development of a new secular spiritual tool based in Celtic Shamanism 23 1.2.2 Dearth of research from the counsellor’s perspective using spiritual tools 25 1.3 Rationale of the research 26 1.3.1 -

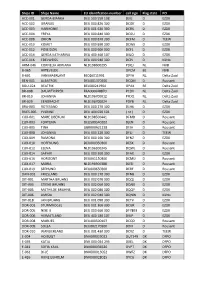

Ships ID Ships Name EU Identifcation Number Call Sign Flag State PO ACC

Ships ID Ships Name EU identifcation number call sign Flag state PO ACC-001 GERDA-BIANKA DEU 500 550 108 DJIG D EZDK ACC-002 URANUS DEU 000 820 300 DCGK D EZDK ACC-003 HARMONIE DEU 001 630 300 DCRK D EZDK ACC-004 FREYA DEU 000 840 300 DCGU D EZDK ACC-008 ORION DEU 000 870 300 DCFM D TEEW ACC-010 KOMET DEU 000 890 300 DCWK D EZDK ACC-012 POSEIDON DEU 000 900 300 DCFL D EZDK ACC-014 GERDA KATHARINA DEU 400 460 107 DIUO D EZDK ACC-016 EDELWEISS DEU 000 940 300 DCPJ D KüNo ARM-046 CORNELIA ADRIANA NLD198600295 PDQJ NL NVB B-065 ARTEVELDE OPCM BE NVB B-601 VAN MAERLANT BE026011991 OPYA NL Delta Zuid BEN-001 ALBATROS DEU001370300 DCQM D Rousant BOU-024 BEATRIX BEL000241964 OPAX BE Delta Zuid BR-008 DAUWTRIPPER FRA000648870 PCDV NL Delta Zuid BR-010 JOHANNA NLD196700012 PFDQ NL Delta Zuid BR-029 EENDRACHT NLD196700024 PDYB NL Delta Zuid BRA-003 ROTESAND DEU 000 270 300 DLHX D EZDK BUES-005 YVONNE DEU 404 020 101 ( nc ) D EZDK CUX-001 MARE LIBERUM NLD198500441 DFMD D Rousant CUX-003 FORTUNA DEU500540102 DJEN D Rousant CUX-005 TINA GBR000A21228 DFJH D Rousant CUX-008 JOHANNA DEU 000 220 300 DFLJ D TEEW CUX-009 RAMONA DEU 000 160 300 DFNZ D EZDK CUX-010 HOFFNUNG DEU000350300 DESX D Rousant CUX-012 ELENA NLD196300345 DQWL D Rousant CUX-014 SAPHIR DEU 000 360 300 DFAX D EZDK CUX-016 HORIZONT DEU001150300 DCMU D Rousant CUX-017 MARIA NLD196900388 DJED D Rousant CUX-019 SEEHUND DEU000650300 DERF D Rousant DAN-001 FRIESLAND DEU 000 170 300 DFNB D EZDK DIT-001 MARTHA BRUHNS DEU 002 070 300 DQQJ D EZDK DIT-003 STIENE BRUHNS DEU 002 060 300 DQNX D EZDK -

Healing Touch: Trouble with Angels

CHRISTIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.O. Box 8500, Charlotte, NC 28271 Feature Article: JAH025 HEALING TOUCH: TROUBLE WITH ANGELS by Sharon Fish Mooney This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 28, number 2 (2005). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org SYNOPSIS Nontraditional health-related practices that involve the hands, based on the assumption that people are energy fields, are becoming increasingly popular. One of the most widely used is Healing Touch, a practice rooted in a variety of belief systems, including Theosophy, spiritism, and Buddhism. Nurses and others certified as Healing Touch practitioners are expected to read a wide range of books on occult philosophy and engage in experiential training that includes information on contacting and channeling “angels” or “spiritual guides.” Healing Touch and related practices such as Therapeutic Touch and Reiki are being welcomed into Christian churches uncritically in the guise of Christian healing practices, based on the belief that the healing associated with them is the same form of healing practiced by Jesus and the first-century Christians. These churches appear to be ignoring biblical injunctions that warn the people of God to have nothing to do with aberrant belief systems, mediums, and with any practices associated with divination. Elisabeth Jensen is a registered nurse and a qualified mid-wife. She has many qualifications in complementary healing methods: she is a Therapeutic Touch Teacher; Melchizedek Method Facilitator; Past, Parallel, and Future Lives Therapist; Certified Angel Intuitive Practitioner; Professional Crystal Healer; Aura Reading and Healing Therapist, and Healing Touch Practitioner. -

Industry Guide Focus Asia & Ttb / April 29Th - May 3Rd Ideazione E Realizzazione Organization

INDUSTRY GUIDE FOCUS ASIA & TTB / APRIL 29TH - MAY 3RD IDEAZIONE E REALIZZAZIONE ORGANIZATION CON / WITH CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI / WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON / IN COLLABORATION WITH CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI / WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF CON IL PATROCINIO DI / UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF FOCUS ASIA CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON/WITH COLLABORATION WITH INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS PROJECT MARKET PARTNERS TIES THAT BIND CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF CAMPUS CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI/WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF MAIN SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS FESTIVAL PARTNERS TECHNICAL PARTNERS ® MAIN MEDIA PARTNERS MEDIA PARTNERS CON / WITH FOCUS ASIA April 30/May 2, 2019 – Udine After the big success of the last edition, the Far East Film Festival is thrilled to welcome to Udine more than 200 international industry professionals taking part in FOCUS ASIA 2019! This year again, the programme will include a large number of events meant to foster professional and artistic exchanges between Asia and Europe. The All Genres Project Market will present 15 exciting projects in development coming from 10 different countries. The final line up will feature a large variety of genres and a great diversity of profiles of directors and producers, proving one of the main goals of the platform: to explore both the present and future generation of filmmakers from both continents. For the first time the market will include a Chinese focus, exposing 6 titles coming from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Thanks to the partnership with Trieste Science+Fiction Festival and European Film Promotion, Focus Asia 2019 will host the section Get Ready for Cannes offering to 12 international sales agents the chance to introduce their most recent line up to more than 40 buyers from Asia, Europe and North America. -

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Corporate Medical Policy Complementary and Alternative Medicine File Name: complementary_and_alternative_medicine Origination: 12/2007 Last CAP Review: 2/2021 Next CAP Review: 2/2022 Last Review: 2/2021 Description of Procedure or Service The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine (NCCIH), a component of the National Institutes of Health, defines complementary, alternative medicine (CAM) as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional or allopathic medicine. While some scientific evidence exists regarding some CAM therapies, for most there are key questions that are yet to be answered through well-designed scientific studies-questions such as whether these therapies are safe and whether they work for the diseases or medical conditions for which they are used. Complementary medicine is used together with conventional medicine. Complementary medicine proposes to add to a proven medical treatment. Alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine. Alternative means the proposed method would possibly replace an already proven and accepted medical intervention. NCCIM classifies CAM therapies into 5 categories or domains: • Whole Medical Systems. These alternative medical systems are built upon complete systems of theory and practice. These systems have evolved apart from, and earlier than, the conventional medical approach used in the U.S. Examples include: homeopathic and naturopathic medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda, Macrobiotics, Naprapathy and Polarity Therapy. • Mind-Body Medicine. Mind-body interventions use a variety of techniques designed to enhance the mind’s capacity to affect bodily functions and symptoms. Some techniques have become part of mainstream practice, such as patient support groups and cognitive-behavioral therapy. -

9783631815052.Pdf

Inclusión, integración, diferenciación IMAGES OF DISABILITY / IMÁGENES DE LA DIVERSIDAD FUNCIONAL Literature, Scenic, Visual, and Virtual Arts / Literatura, artes escénicas, visuales y virtuales Edited by Susanne Hartwig and Julio Enrique Checa Puerta VOLUME 2 Susanne Hartwig (ed.) Inclusión, integración, diferenciación La diversidad funcional en la literatura, el cine y las artes escénicas Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Unterstützt durch den Publikationsfonds der Universität Passau El libro ha sido publicado gracias al apoyo del programa Hispanex ISSN 2569-586X ISBN 978-3-631-79803-4 (Print) • E-ISBN 978-3-631-81505-2 (E-Book) E-ISBN 978-3-631-81506-9 (EPUB) • E-ISBN 978-3-631-81507-6 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b16655 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Susanne Hartwig Peter Lang GmbH International Academic Publishers Berlin 2020 Peter Lang – Berlin · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien www.peterlang.com Contenido Susanne Hartwig Introducción: los mundos posibles y la inclusión de la diversidad funcional ................................................................................................................. 9 I. Inclusión en el escenario Julio -

Therapeutic Massage

5/10/2018 Facilitating the Body’s Natural Healing Ability during Stress, Illness, and Pain Therapeutic Massage 2700 BCE: First known Chinese text ”The Yellow Emperor’s Classic Book of Internal Medicine” Published into English 1949. A staple in massage therapy training as well as acupuncture, acupressure, and herbology. 2500 BCE: Egyptian tomb paintings show massage was part of their medical tradition. 1500 and 500 BCE: First known written massage therapy traditions come from India. The art of healing touch was used in their practice of Ayurvedic (life health) medicine. Ayurveda is regarded as the originating basis of holistic health combining, massage, meditation, relaxation, and flower essence. 1800’s Dr Ling, a Swedish physician, educator, and gymnast, developed a method of movement that became known as the Swedish Movement System which became the foundation for Swedish massage commonly used in the West. Johan Mezger is credited with defining the basic hand strokes used in Swedish Massage. 1 5/10/2018 Therapeutic Massage in Medicine and Nursing Late 1800’s. Hundreds of care givers trained in Swedish Movement and Massage for patients in Sanitariums 1900’s Nursing students trained in basic back, arm, hand, and scalp/head massage. Late 1980’s routine massage included in PM care provided by nurses begins to disappear and is fazed out in the curriculum of Nursing Education 1990’s Medical and Nursing Care move from High Touch to High Tech Benefits of Therapeutic Massage Relieves pain Relaxes painful muscles, tendons, and joints Relieves stress and anxiety Possibly helps to “close the pain gate” by stimulating competing nerve fibers and impeding pain messages to and from the brain. -

Developmental Therapeutics Immunotherapy

DEVELOPMENTAL THERAPEUTICS—IMMUNOTHERAPY 2500 Oral Abstract Session Clinical activity of systemic VSV-IFNb-NIS oncolytic virotherapy in patients with relapsed refractory T-cell lymphoma. Joselle Cook, Kah Whye Peng, Susan Michelle Geyer, Brenda F. Ginos, Amylou C. Dueck, Nandakumar Packiriswamy, Lianwen Zhang, Beth Brunton, Baskar Balakrishnan, Thomas E. Witzig, Stephen M Broski, Mrinal Patnaik, Francis Buadi, Angela Dispenzieri, Morie A. Gertz, Leif P. Bergsagel, S. Vincent Rajkumar, Shaji Kumar, Stephen J. Russell, Martha Lacy; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ; Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, Roches- ter, MN; Vyriad and Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN Background: Oncolytic virotherapy is a novel immunomodulatory therapeutic approach for relapsed re- fractory hematologic malignancies. The Indiana strain of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus was engineered to encode interferon beta (IFNb) and sodium iodine symporter (NIS) to produce VSV-IFNb-NIS. Virally en- coded IFNb serves as an index of viral proliferation and enhances host anti-tumor immunity. NIS was in- serted to noninvasively assess viral biodistribution using SPECT/PET imaging. We present the results of the phase 1 clinical trial NCT03017820 of systemic administration of VSV-IFNb-NIS among patients (pts) with relapsed refractory Multiple Myeloma (MM), T cell Lymphoma (TCL) and Acute myeloid Leu- 9 kemia (AML). Methods: VSV-IFNb-NIS was administered at 5x10 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infec- 11 tious dose) dose level 1 to dose level 4, 1.7x10 TCID50. The primary objective was to determine the maximum tolerated dose of VSV-IFNb-NIS as a single agent. Secondary objectives were determination of safety profile and preliminary efficacy of VSV-IFNb-NIS. -

Programme Book

10th European Public Health Conference OVERVIEW PROGRAMME Sustaining resilient WEDNESDAY 1 NOVEMBER THURSDAY 2 NOVEMBER FRIDAY 3 NOVEMBER SATURDAY 4 NOVEMBER 09:00 – 12:30 09:00 – 10:30 08:30 - 09:30 08:30 - 10:00 Pre-conferences Parallel sessions 1 Parallel sessions 4 Parallel session 8 09:40 - 10:40 10:10 - 11:10 and healthy communities Plenary 3 Parallel session 9 10:30 – 11:00 10:30 – 11:00 10:40 – 11:10 11:10 – 11:40 Coffee/tea Coffee/tea Coffee/tea Coffee/tea 11th European Public Health Conference 2018 12th European Public Health Conference 2019 11:00 – 12:00 11:10 - 12:10 11:40 - 13:10 Ljubljana, Slovenia Marseille, France PROGRAMME Plenary 1 Parallel sessions 5 Parallel session 10 12:30 – 13:30 12:00 – 13:15 12:10 – 13:40 13:10 – 14:10 Lunch for pre-conference Lunch – Lunch symposiums and Lunch – Lunch symposiums Lunch – Join the Networks delegates only Join the Networks and Join the Networks 13:30 – 17:00 13:15 - 14:15 13:40 - 14:40 14:10 - 15:10 Pre-conferences Plenary 2 Plenary 4 Plenary 5 14:25 – 15:25 14:50-15:50 15:10 – 16:00 Parallel sessions 2 Parallel sessions 6 Closing Ceremony Winds of Change: towards new ways Building bridges for solidarity 15:00 – 15:30 15:25 – 15:55 15:50 – 16:20 of improving public health in Europe and public health Coffee/tea Coffee/tea Coffee/tea 17:00 16:05 – 17:05 16:20 - 17:50 28 November - 1 December 2018 20 - 23 November 2019 End of Programme Parallel sessions 3 Parallel sessions 7 Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana Marseille Chanot, Marseille 17:15 - 18:00 Opening Ceremony @EPHConference #EPH2018 -

The University of Chicago Homo-Eudaimonicus

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO HOMO-EUDAIMONICUS: AFFECTS, BIOPOWER, AND PRACTICAL REASON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY COMMITTEE ON THE CONCEPTUAL AND HISTORICAL STUDIES OF SCIENCE AND DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY FRANCIS ALAN MCKAY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Francis Mckay All Rights Reserved If I want to be in the world effectively, and have being in the world as my art, then I need to practice the fundamental skills of being in the world. That’s the fundamental skill of mindfulness. People in general are trained to a greater or lesser degree through other practices and activities to be in the world. But mindfulness practice trains it specifically. And our quality of life is greatly enhanced when we have this basic skill. — Liam Mindfulness is a term for white, middle-class values — Gladys Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ viii Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... x Chapter 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1: A Science and Politics of Happiness .............................................................................. 1 1.2: Global Well-Being ........................................................................................................ -

Integration of Reiki, Healing Touch and Therapeutic Touch Into Clinical Services

Office of Clinical Integration and Evidence-Based Practice April 2018 OREGON HEALTH AND SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF CLINICAL INTEGRATION AND EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE Evidence-Based Practice Summary Integration of Reiki, Healing Touch and Therapeutic Touch into Clinical Services Prepared for: Richard Soehl, MSN, RN; Helen Turner, DNP, PCNS; Janani Buxton, RN; Kathleen Buhler, MSN; Brenda Quint-Gaebel, MPH-HA; Michael Aziz, MD Authors: Marcy Hager, MA BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE The concept of subtle energy and methods of its use for healing has been described by numerous cultures for thousands of years.13 These vital energy concepts all refer to subtle or nonphysical energies that permeate existence and have specific effects on the body-mind of all conscious beings.13 Although many of these practices have been used over millennia in various cultural communities for the purpose of healing physical and mental disorders, they have only recently been examined by current Western empirical methods.13 These modalities, collectively termed by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine as biofield therapies 19, began to be more widely taught and used by U.S. providers in many clinical and hospital settings starting in the 1970s.13 Biofield therapies in clinical practice use both hands-on and hands-off (nonphysical contact) procedures.17, 29 Biofield therapies have previously been used for reducing pain and discomfort in patients with cancer, chronic pain, and fatigue and anxiety, as well as for improving general health.23 Additionally, biofield therapies have shown positive effects on biological factors, such as hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, immunological factors, vital signs, healing rate of wounds, and arterial blood flow in the lower extremities.