Qat Yemen.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tor Yemen Nutrition Cluster Revi

Yemen Nutrition Cluster كتله التغذية اليمن https://www.humanitarianresponse.info https://www.humanitarianresponse.info /en/operations/yemen/nutrition /en/operations/yemen/nutrition XXXXXXXX XXXXXXXX YEMEN NUTRITION CLUSTER TERMS OF REFERENCE Updated 23 April 2018 1. Background Information: The ‘Cluster Approach1’ was adopted by the interagency standing committee as a key strategy to establish coordination and cooperation among humanitarian actors to achieve more coherent and effective humanitarian response. At the country level, the aim is to establish clear leadership and accountability for international response in each sector and to provide a framework for effective partnership and to facilitat strong linkages among international organization, national authorities, national civil society and other stakeholders. The cluster is meant to strengthen rather than to replace the existing coordination structure. In September 2005, IASC Principals agreed to designate global Cluster Lead Agencies (CLA) in critical programme and operational areas. UNICEF was designated as the Global Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency (CLA). The nutrition cluster approach was adopted and initiated in Yemen in August 2009, immediately after the break-out of the sixth war between government forces and the Houthis in Sa’ada governorate in northern Yemen. Since then Yemen has continued to face complex emergencies that are largely conflict-generated and in part aggravated by civil unrest and political instability. These complex emergencies have come on the top of an already fragile situation with widespread poverty, food insecurity and underdeveloped infrastructure. Since mid-March 2015, conflict has spread to 20 of Yemen’s 22 governorates, prompting a large-scale protection crisis and aggravating an already dire humanitarian crisis brought on by years of poverty, poor governance and ongoing instability. -

Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen's Red Sea Coast

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2017 “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. GINGKO LIBRARY ART SERIES Senior Editor: Melanie Gibson Architectural Heritage of Yemen Buildings that Fill my Eye Edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand First published in 2017 by Gingko Library 70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH Copyright © 2017 selection and editorial material, Trevor H. J. Marchand; individual chapters, the contributors. The rights of Trevor H. J. Marchand to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Aden Sub- Office May 2020

FACT SHEET Aden Sub- Office May 2020 Yemen remains the world’s Renewed fighting in parts of UNHCR and partners worst humanitarian crisis, with the country, torrential rains provide protection and more than 14 million people and deadly flash floods and assistance to displaced requiring urgent protection and now a pandemic come to families, refugees, asylum- assistance to access food, water, exacerbate the already dire seekers and their host shelter and health. situation of millions of people. communities. KEY INDICATORS 1,082,430 Number of internally displaced persons in the south DTM March 2019 752,670 Number of returnees in the south DTM March 2019 161,000 UNHCR’s partner staff educate a Yemeni man on COVID-19 and key Number of refugees and asylum seekers in the preventive measures during a door-to-door distribution of hygiene material south UNHCR April 2020 including soap, detergent in Basateen, in Aden © UNHCR/Mraie-Joelle Jean-Charles, April 2020. UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 85 National Staff 14 International Staff Offices: 1 Sub Office in Aden 1 Field Office in Kharaz 2 Field Units in Al Mukalla and Turbah www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Aden Sub- Office/ May 2020 Main activities Protection INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS Protection Cluster ■ The Protection Cluster led by UNHCR and co-led by Intersos coordinates the delivery of specialised assistance to people with specific protection needs, including victims of violence and support to community centres, programmes, and protection networks. ■ At the Sub-National level, the Protection Cluster includes more than 40 partners. ■ UNHCR seeks to widen the protection space through protection monitoring (at community and household levels) and provision of protection services including legal, psychosocial support, child protection and prevention and response to sexual and gender-based violence. -

On Conservation and Development: the Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen*

On Conservation and Development: The Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen* Deepa Mehta Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation** Columbia University in the City of New York New York, NY 10027, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT A study of small and medium enterprises that make up the highly specialized mud brick construction industry in southern Yemen reveals how the practice has been sustained through closely-linked regional production chains and strong firm inter-relationships. Yemen, as it struggles to grow as a nation, has the potential to gain from examining the contribution that these institutions make to an ancient building practice that still continues to provide jobs and train new skilled workers. The impact of these firms can be bolstered through formal recognition and capacity development. UNESCO, ICOMOS, and other conservation agencies active in the region provide a model that emphasizes architectural conservation as well as the concurrent development of the existing socioeconomic linkages. The primary challenge is that mud brick construction is considered obsolete, but evidence shows that the underlying institutions are resilient and sustainable, and can potentially provide positive regional policy implications. Key Words: conservation, planning, development, informal sector, capacity building, Yemen, mud brick construction. * Paper prepared for GLOBELICS 2009: Inclusive Growth, Innovation and Technological Change: education, social capital and sustainable development, October 6th – -

Anglais (English

YEMEN Al Hudaydah Displacement/Response Update 03 – 09 August Al Hudaydah Aden Ibb/Taizz Sana’a Hub Hub Hub Hub Displacement Response Displacement Response Displacement Response Displacement Response 22,964 HHs 13,129 HHs 3,068 HHs 1,695 HHs 4,713 HHs 1,140 HHs 25,396 HHs 749 HHs Key Figures Overview In Al Hudaydah hub, strikes near AlThawra hospital, a fish market, and the radio building in Al Hudaydah City result in several deaths and injuries. These a�acks against civilian persons and objects are a viola�on of IHL (Interna�onal Humanitarian Law) and may cons�tute a war crime. In Sana’a hub, authori�es agreed to allow a discreet cash for rent scheme for 278 families from Al Hudaydah who have recently been hosted in 9 schools in Amanat Al Asimah. SNC (Sub-Na�onal Cluster) organized a mee�ng with the Partners working in the Transit and IDP hos�ng sites (schools) to discuss sequences for the implementa�on of the agreed scheme to ensure capturing the needs of sites residents through mul�-sectoral needs assessment, payment of cash for rent, restora�on of schools and iden�fica- �on of new site for con�nued registra�on of new IDPs from Al Hudaydah. ADRA reported that there are 36 IDP families who are residing in Mahw Al Omiah school and Al Hamzah school in Dhamar governorate In Aden hub, the security situa�on in Aden governorate worsened further this week with two IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) explosions in Enma’a city and Al Mualla district also the city experienced security unrest including blocked roads due to public protest and security deployments that spread in various loca�ons. -

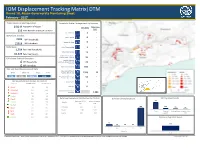

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017 Total Governorate Population Household Shelter Arrangements by Location 2 Population of Abyan 1 0.56 M IDPs (HH) Returnees (HH) 116 Total Number of Unique Locations School Buildings 2 - IDPs from Conflict Health Facilities 0 - 2103 IDP Households Religious Buildings 0 - 12618 IDP Individuals Returnees Other Private Building 5 - 1,754 Returnee Households Other Public Building 15 - 10,524 Returnee Persons Settlements (Grouped of Families) Urban and Rural - IDPs from Natural Disasters 24 Isolated/ dispersed IDP Households settlements (detatched from 26 - 0 a location) IDP Individuals 0 Rented Accomodation 650 - Sex and Age Dissagregated Data Host Families Who are Men Women Boys Girls Relatives (no rent fee) 1326 70 21% 23% 25% 31% Host Families Who are not Relatives (no rent fee) 54 - IDP Household Distribution Per District Second Home 1 - District IDP HH in Jan IDP HH in Feb Ahwar 32 29 Unknown 0 - Al Mahfad 379 264 Original House of Habitual Al Wade'a 110 96 Residence 1,684 Jayshan 15 25 Khanfir 505 499 Returnee Household Distribution Per District Duration of Displacement IDP Top Most Needs Returnee HH in Returnee HH in 79% Lawdar 259 278 District Jan Feb Mudiyah 34 35 Al Wade'a 130 130 92% 12% 6% Rasad 241 201 2% Khanfir 1,200 1,200 Sarar 121 114 Food Financial Drinking Water Household Items Lawdar 424 424 support (NFI) Sibah 248 221 Zingibar 221 341 Returnee Top Most Needs 8% 0% 0% 0% 100% 1-3 4-6 7-9 10-12 12 > Months Food 1 Population -

A New Model for Defeating Al Qaeda in Yemen

A New Model for Defeating al Qaeda in Yemen Katherine Zimmerman September 2015 A New Model for Defeating al Qaeda in Yemen KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2015 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Part I: Al Qaeda and the Situation in Yemen ................................................................................................. 5 A Broken Model in Yemen ...................................................................................................................... 5 The Collapse of America’s Counterterrorism Partnership ........................................................................ 6 The Military Situation in Yemen ........................................................................................................... 10 Yemen, Iran, and Regional Dynamics ................................................................................................... 15 The Expansion of AQAP and the Emergence of ISIS in Yemen ............................................................ 18 Part II: A New Strategy for Yemen ............................................................................................................. 29 Defeating the Enemy in Yemen ............................................................................................................ -

Final Report 2006 Presidential and Local Council Elections Yemen

EU Election Observation Mission, Yemen 2006 1 Final Report on the Presidential and Local Council Elections European Union Election Observation Mission Mexico 2006 European Union Election Observation Mission Yemen 2006 FINAL REPORT YEMEN FINAL REPORT Presidential and Local Council Elections 20 September 2006 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION This report was produced by the EU Election Observation Mission and presents the EU EOM’s findings on the 20 September 2006 Presidential and Local Council Elections in the Republic of Yemen. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the Commission. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 II. INTRODUCTION 3 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 4 A: Political Context of the 20 September elections 4 B: Key Political Actors in the 2006 Elections 5 C: Cross-Party Agreement on Electoral Principles 6 (the ‘18 June Agreement’) IV. LEGAL ISSUES 6 A: Legal Framework for the 2006 Elections 6 B: Enforcement of Legal Provisions on Elections 6 C: Candidate Registration 9 D: Electoral Systems in Yemen 10 Presidential Elections 10 Local Council Elections 10 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION 11 A: Structure and Composition of the Election Administration 11 B: The Administration of the 2006 Elections 13 C: Arrangements for Special Polling Stations 15 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION 16 A: The Right to Vote 16 B: Voter Registration Procedures 17 VII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION A: Registration of Candidates of the Presidential Elections 18 B: Registration of Candidates for the Local Council Elections 18 VIII. -

October 2020

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN October 2020 *** All Health Cluster Coordination meetings are conducted virtually. YEMEN Emergency Level: Level 3 Reporting period: October 2020 7.3M 17.9M Targeted with Health 3.34 508M 1Million PIN of Health Assistance Interventions Million** IDPs Funds required Returnees HIGHLIGHTS HEALTH SECTOR A total of 1,958 Health Facilities (16 Governorate 71 HEALTH CLUSTER PARTNERS Hospitals, 131 District Hospitals, 62 General 9.7 M PEOPLE IN ACUTE NEED Hospitals, 21 Specialized Hospitals, 458 Health KITS DELIVERED TO HEALTH FACILITIES/PARTNERS Centers and 1,270 Health Units) are being 13 IEHK BASIC KITS supported by Health Cluster Partners. 13 IEHK SUPPLEMENTARY KITS 1 TRAUMA KITS As of the 24th of October 2020, 2064 positive 47 OTHER TYPES OF KITS COVID-19 cases and 601 deaths have been SUPPORTED HEALTH FACILITIES confirmed by MOH Aden (COVID-19 reports are only from the southern governorates). 1,958 HEALTH FACILITIES The cumulative total number of suspected Cholera 1,264,050 OUTPATIENT CONSULTATIONS cases from the 1st of January to the 31 of Oct, 11,615 SURGERIES 2020 is 208606 with 68 associated deaths (CFR ASSISTED DELIVERIES (NORMAL & 51,972 0.03%). Children under five represent 26% whilst C/S) the elderly above 60 years of age accounted for VACCINATION 6.0% of total suspected cases. The outbreak has so far affected in 2020 : 22 of 23 governorates and 94,025 PENTA 3 299 of 333 districts in Yemen. EDEWS As of 31st of October 2020, Health Cluster Partners 1,982 SENTINEL SITES supported a total number of 142 DTCs and 226 FUNDING US$ ORCs in 169 Priority districts. -

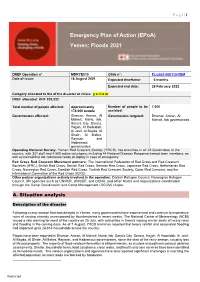

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Yemen: Floods 2021

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Yemen: Floods 2021 DREF Operation n° MDRYE010 Glide n°: FL-2021-000110-YEM Date of issue: 16 August 2021 Expected timeframe: 6 months Expected end date: 28 February 2022 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: y e l l o w DREF allocated: CHF 205,332 Total number of people affected: Approximately Number of people to be 7,000 174,000 people assisted: Governorates affected: Dhamar, Amran, Al Governorates targeted: Dhamar, Amran, Al Mahwit, Marib, Ibb, Mahwit, Ibb governorates Sana’a City, Sana’a, Hajjah, Al Hodeidah, Al Jawf, Al Bayda, Al Dhale, Al Mahra, Raymah and Hadramout governorates Operating National Society: Yemen Red Crescent Society (YRCS) has branches in all 22 Governates of the country, with 321 staff and 4,500 active volunteers, including 44 National Disaster Response trained team members, as well as trained first aid volunteers ready to deploy in case of emergency. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners: The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), British Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Turkish Red Crescent Society, Qatar Red Crescent, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Danish Refugee Council, Norwegian Refugee Council, UN agencies such as UNHCR, UNICEF, and OCHA, and other NGOs and organizations coordinated through the Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) cluster. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Following a rainy season that was delayed in Yemen, many governorates have experienced and continue to experience rains of varying intensity accompanied by thunderstorms in recent weeks. -

Aid Security and COVID-19 Latest Available Information on COVID-19 Developments Impacting the Security of Aid Work and Operations

Aid Security and COVID-19 Latest available information on COVID-19 developments impacting the security of aid work and operations. Access the COVID-19 Bulletin 6 Aid Security Overview Data on HDX to see the events referred to in this bulletin. 22 May 2020 This bulletin from the Aid The Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas Security and COVID-19 The effect of airstrikes, shelling and IEDs on health care and the COVID-19 health response in March and series highlights the use of April 2020. explosive weapons in populated areas in Syria, Yemen, and Libya during On 23 March 2020, UN Secretary General António Guterres called for a global ceasefire amid the COVID-19 March and April 2020. pandemic. Reminding the world that in war-ravaged countries health systems have often collapsed and that health professionals have been targeted, he called on warring parties to cease hostilities, silence guns, stop the It is based on publicly available reports of incidents that injured artillery, and end airstrikes on civilians. or killed workers, damaged health facilities or health Turkey and Russia had already agreed to a ceasefire in Syria’s Idlib province on 05 March after violence transport at the time of the escalated that left scores of Turkish and Syrian soldier’s dead. The Houthi rebels, Yemeni government, and COVID-19 response. Saudi Arabia, which leads the military campaign in support of the Yemeni government. initially responded Event descriptions have not positively to the UN appeal for a ceasefire. In Libya, the main protagonists in the conflict also initially welcomed been independently verified. -

Yemen's Revolutionary Moment, Collective Memory and Contentious

The London School of Economics and Political Science Citizen Revolt for a Modern State: Yemen’s Revolutionary Moment, Collective Memory and Contentious Politics sur la longue durée Tobias Thiel A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, 2015 Yemen’s Revolutionary Moment, Collective Memory and Contentious Politics | 2 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,247 words. Yemen’s Revolutionary Moment, Collective Memory and Contentious Politics | 3 ABSTRACT 2011 became a year of revolt for the Middle East and North Africa as a series of popular uprisings toppled veteran strongmen that had ruled the region for decades. The contentious mobilisations not only repudiated orthodox explanations for the resilience of Arab autocracy, but radically asserted the ‘political imaginary’ of a sovereign and united citizenry, so vigorously encapsulated in the popular slogan al-shaʿb yurīd isqāṭ al-niẓām (the people want to overthrow the system).