Novi Zvuk 51.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAZU2012.Pdf

ISSN 0374-0315 LETOPIS SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI 63/2012 THE YEARBOOK OF THE SLOVENIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS VOLUME 63/2012 ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ET ARTIUM SLOVENICAE LIBER LXIII (2012) LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 1 4.7.2013 9:28:35 LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 2 4.7.2013 9:28:35 SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI 63. KNJIGA 2012 THE YEARBOOK OF THE SLOVENIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS VOLUME 63/2012 LJUBLJANA 2013 LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 3 4.7.2013 9:28:35 SPREJETO NA SEJI PREDSEDSTVA SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI DNE 21. JANUARJA 2013 Naslov / Address SLOVENSKA AKADEMIJA ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI SI-1000 LJUBLJANA, Novi trg 3, p. p. 323, telefon: (01) 470-61-00 faks: (01) 425-34-23 elektronska pošta: [email protected] spletna stran: www.sazu.si LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 4 4.7.2013 9:28:35 VSEBINA / CONTENTS I. ORGANIZACIJA SAZU / SASA ORGANIZATION �������������������������������������� 7 Skupščina, redni, izredni, dopisni člani / SASA Assembly, Full Members, Associate Members and Corresponding Members. 9 II. POROČILO O DELU SAZU / REPORT ON THE WORK OF SASA. 17 Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti v letu 2012. 19 Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts in the year 2012 . 25 Delo skupščine ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 31 I. Razred za zgodovinske in družbene vede . 41 II. Razred za filološke in literarne vede . 42 III. Razred za matematične, fizikalne, kemijske in tehniške vede . 43 IV. Razred za naravoslovne vede ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 45 V. Razred za umetnosti. 46 VI. Razred za medicinske vede ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 50 Kabinet akademika Franceta Bernika . 51 Svet za varovanje okolja ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 51 Svet za energetiko . 51 Svet za kulturo in identiteto prostora Slovenije. -

From Mystery to Spectacle Essays on Death in Serbia from the 19Th-21St Century Српска Академија Наука И Уметности Етнографски Институт

ISBN 978-86-7587-079-1 Aleksandra Pavićević From Mystery to Spectacle Essays on Death in Serbia from the 19th-21st Century СрпСка академија наука и уметноСти етнографСки инСтитут посебна издања књига 83 Александра Павићевић Од мистерије до спектакла Есеји о смрти у Србији од 19–21. века уредник драгана радојичић Београд 2015. SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS INSTITUTE OF ETHNOGRAPHY SPECIAL EDITIONS Volume 83 Aleksandra Pavićević From Mystery to Spectacle Essays on Death in Serbia from the 19th–21st Century Editor Dragana Radojičić BelgRADe 2015. Издавач: етнографСки инСтитут Сану кнез михајлова 36/4, Београд, тел.2636 804 За издавача: драгана рaдојичић Рецензенти: др коста николић др ивица тодоровић др Лада Стевановић Секретар редакције: марија Ђокић Преводи и лектура: олга кидишевић, нил мек доналд (Neil Mac Donald), маша матијашевић, Ђурђина Шијаковић ма, др александра павићевић Корице и техничка припрема: Бранислав пантовић и атеље Штампа: Чигоја Тираж: 500 примерака Штампање публикације финансирано је из средстава министарства просвете, науке и технолошког развоја републике Србије. публикација је резултат рада на пројектима 177028 и 47016 Contents About this book ....................................................................................7 In or out of Cultural and Historical Matrix? Researching Death in Serbian ethnology during the Second Half of the 20th Century .............9 Death and Funeral in Serbia at the Beginning of third Millennia. Attitudes and Rituals of Common People ..........................................23 -

No Limits Freediving

1 No Limits Freediving "The challenges to the respiratory function of the breath-hold diver' are formidable. One has to marvel at the ability of the human body to cope with stresses that far exceed what normal terrestrial life requires." Claes Lundgren, Director, Center for Research and Education in Special Environments A woman in a deeply relaxed state floats in the water next to a diving buoy. She is clad in a figure-hugging wetsuit, a dive computer strapped to her right wrist, and another to her calf. She wears strange form-hugging silicone goggles that distort her eyes, giving her a strange bug-eyed appearance. A couple of meters away, five support divers tread water near a diving platform, watching her perform an elaborate breathing ritual while she hangs onto a metal tube fitted with two crossbars. A few meters below the buoy, we see that the metal tube is in fact a weighted sled attached to a cable descending into the dark-blue water. Her eyes are still closed as she begins performing a series of final inhalations, breathing faster and faster. Photographers on the media boats snap pictures as she performs her final few deep and long hyperventilations, eliminating carbon dioxide from her body. Then, a thumbs-up to her surface crew, a pinch of the nose clip, one final lungful of air, and the woman closes her eyes, wraps her knees around the bottom bar of the sled, releases a brake device, and disappears gracefully beneath the waves. The harsh sounds of the wind and waves suddenly cease and are replaced by the effervescent bubbling of air being released from the regulators of scuba-divers. -

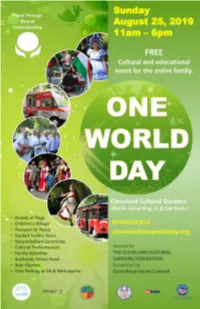

Program Booklet

The Irish Garden Club Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians Murphy Irish Arts Association Proud Sponsors of the Irish Cultural Garden Celebrate One World Day 2019 Italian Cultural Garden CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE (TRI-C®) SALUTES CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDENS FEDERATION’S ONE WORLD DAY 2019 PEACE THROUGH MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING THANK YOU for 74 years celebrating Cleveland’s history and ethnic diversity The Italian Cultural Garden was dedicated in 1930 “as tri-c.edu a symbol of Italian culture to American democracy.” 216-987-6000 Love of Beauty is Taste - The Creation of Beauty is Art 19-0830 216-916-7780 • 990 East Blvd. Cleveland, OH 44108 The Ukrainian Cultural Garden with the support of Cleveland Selfreliance Federal Credit Union celebrates 28 years of Ukrainian independence and One World Day 2019 CZECH CULTURAL GARDEN 880 East Blvd. - south of St. Clair The Czech Garden is now sponsored by The Garden features many statues including composers Dvorak and Smetana, bishop and Sokol Greater educator Komensky – known as the “father of Cleveland modern education”, and statue of T.G. Masaryk founder and first president of Czechoslovakia. The More information at statues were made by Frank Jirouch, a Cleveland czechculturalgarden born sculptor of Czech descent. Many thanks to the Victor Ptak family for financial support! .webs.com DANK—Cleveland & The German Garden Cultural Foundation of Cleveland Welcome all of the One World Day visitors to the German Garden of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens The German American National congress, also known as DANK (Deutsch Amerikan- ischer National Kongress), is the largest organization of Americans of Germanic descent. -

At the Margins of the Habsburg Civilizing Mission 25

i CEU Press Studies in the History of Medicine Volume XIII Series Editor:5 Marius Turda Published in the series: Svetla Baloutzova Demography and Nation Social Legislation and Population Policy in Bulgaria, 1918–1944 C Christian Promitzer · Sevasti Trubeta · Marius Turda, eds. Health, Hygiene and Eugenics in Southeastern Europe to 1945 C Francesco Cassata Building the New Man Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy C Rachel E. Boaz In Search of “Aryan Blood” Serology in Interwar and National Socialist Germany C Richard Cleminson Catholicism, Race and Empire Eugenics in Portugal, 1900–1950 C Maria Zarimis Darwin’s Footprint Cultural Perspectives on Evolution in Greece (1880–1930s) C Tudor Georgescu The Eugenic Fortress The Transylvanian Saxon Experiment in Interwar Romania C Katherina Gardikas Landscapes of Disease Malaria in Modern Greece C Heike Karge · Friederike Kind-Kovács · Sara Bernasconi From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File Public Health in Eastern Europe C Gregory Sullivan Regenerating Japan Organicism, Modernism and National Destiny in Oka Asajirō’s Evolution and Human Life C Constantin Bărbulescu Physicians, Peasants, and Modern Medicine Imagining Rurality in Romania, 1860–1910 C Vassiliki Theodorou · Despina Karakatsani Strengthening Young Bodies, Building the Nation A Social History of Child Health and Welfare in Greece (1890–1940) C Making Muslim Women European Voluntary Associations, Gender and Islam in Post-Ottoman Bosnia and Yugoslavia (1878–1941) Fabio Giomi Central European University Press Budapest—New York iii © 2021 Fabio Giomi Published in 2021 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). -

Premio Corso Salani 2015

il principale appuntamento italiano con il cinema dell’Europa centro orientale un progetto di Alpe Adria Cinema Alpe Adria Cinema 26a edizione piazza Duca degli Abruzzi 3 sala Tripcovich / teatro Miela 34132 Trieste / Italia 16-22 gennaio 2015 tel. +39 040 34 76 076 fax +39 040 66 23 38 [email protected] con il patrocinio di www.triesteflmfestival.it Comune di Trieste twitter.com/TriesteFilmFest Direzione Generale per il Cinema – facebook.com/TriesteFilmFest Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo con il contributo di Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia Creative Europe – MEDIA Programme CEI – Central European Initiative Provincia di Trieste Comune di Trieste Direzione Generale per il Cinema – Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo CCIAA – Camera di Commercio di Trieste con il sostegno di Lux Film Prize Istituto Polacco – Roma con la collaborazione di Fondazione Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi – Trieste Fondo Audiovisivo FVG Associazione Casa del Cinema di Trieste La Cappella Underground FVG Film Commission Eye on Films Associazione Culturale Mattador Associazione Corso Salani Centro Ceco di Milano media partner mymovies.it media coverage by Sky Arte HD direzione artistica promozione, coordinamento volontari biglietteria Annamaria Percavassi e direzione di sala Rossella Mestroni, Alessandra Lama Fabrizio Grosoli Patrizia Pepi Gioffrè desk accrediti presidente comunicazione, progetto grafco Ambra De Nobili organizzazione generale immagine coordinata e allestimenti Cristina Sain Claimax -immagina.organizza.comunica- -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

How to Help Someone Having a Panic Attack

How to Help Someone Having a Panic Attack 1. Understand what a panic attack is. A panic attack is a sudden attack of extreme anxiety. It can occur without warning and for no obvious reason. The symptoms are listed under the tips sections of this article. In extreme cases, the symptoms may be accompanied by an acute fear of dying. Although they are quite distressing, panic attacks are not usually life-threatening and can last from 5 - 20 minutes. It is important to note that the signs and symptoms of a panic attack can be similar to those of a heart attack. 2. If this is the first time the person has had something like this, seek emergency medical attention. When in doubt, it is always best to seek immediate medical attention. If the person has diabetes, asthma or other medical problems, seek medical help. 3. Find out the cause of the attack. Talk to the person and determine if he or she is having a panic attack and not another kind of medical emergency (such as a heart or asthma attack) which would require immediate medical attention. Check that the cause of poor breathing is not asthma, as asthma is an entirely different condition and requires different treatments. WARNINGS • Panic attacks, especially to someone who has never had one before, often seem like heart attacks. But heart attacks can be deadly, and if there's any question as to which one it is, it's best to call emergency services. • It should be noted that many asthma sufferers have panic attacks. -

THE WARP of the SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-Westernism, Russophilia, Traditionalism

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA studies17 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism... BELGRADE, 2016 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism… Edition: Studies No. 17 Publisher: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia www.helsinki.org.rs For the publisher: Sonja Biserko Reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Dubravka Stojanović Prof. Dr. Momir Samardžić Dr Hrvoje Klasić Layout and design: Ivan Hrašovec Printed by: Grafiprof, Belgrade Circulation: 200 ISBN 978-86-7208-203-6 This publication is a part of the project “Serbian Identity in the 21st Century” implemented with the assistance from the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. CONTENTS Publisher’s Note . 5 TRANSITION AND IDENTITIES JOVAN KOMŠIĆ Democratic Transition And Identities . 11 LATINKA PEROVIĆ Serbian-Russian Historical Analogies . 57 MILAN SUBOTIĆ, A Different Russia: From Serbia’s Perspective . 83 SRĐAN BARIŠIĆ The Role of the Serbian and Russian Orthodox Churches in Shaping Governmental Policies . 105 RUSSIA’S SOFT POWER DR. JELICA KURJAK “Soft Power” in the Service of Foreign Policy Strategy of the Russian Federation . 129 DR MILIVOJ BEŠLIN A “New” History For A New Identity . 139 SONJA BISERKO, SEŠKA STANOJLOVIĆ Russia’s Soft Power Expands . 157 SERBIA, EU, EAST DR BORIS VARGA Belgrade And Kiev Between Brussels And Moscow . 169 DIMITRIJE BOAROV More Politics Than Business . 215 PETAR POPOVIĆ Serbian-Russian Joint Military Exercise . 235 SONJA BISERKO Russia and NATO: A Test of Strength over Montenegro . -

!001 Deo1 Zbornik MTC 2016 Ispr FINAL 27 Jun.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serbian Academy of Science and Arts Digital Archive (DAIS) I MUSICOLOGICAL STUDIES: MONOGRAPHS MUSIC: TRANSITIONS/CONTINUITIES Department of Musicology Faculty of Music, University of Arts in Belgrade II Department of Musicology, Faculty of Music, Belgrade MUSICOLOGICAL STUDIES: MONOGRAPHS MUSIC: TRANSITIONS/CONTINUITIES Editors Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman Vesna Mikić Tijana Popović Mladjenović Ivana Perković Editor-in-Chief of the Faculty of Music Publications Gordana Karan For Publisher Ljiljana Nestorovska Dean of the Faculty of Music ISBN 978-86-88619-73-8 The publication was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia. III MUSIC: TRANSITIONS / CONTINUITIES Editors Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman Vesna Mikić Tijana Popović Mladjenović Ivana Perković Belgrade 2016 Marija Maglov, Transitions in the Pgp-Rtb/Pgp-Rts Reflected in the Classical Music Editions 309 Marija Maglov TRANSITIONS IN THE PGP-RTB/PGP-RTS REFLECTED IN THE CLASSICAL MUSIC EDITIONS* ABSTRACT: This paper deals with the production of classical music records in the Yugoslav label PGP-RTB/PGP-RTS since its foundation in 1968 up to the present. The paper focuses on differentiation of editions released before and during the political, economic and cultural transitions in the ’90s. Last decades of the twentieth century also marked the technological transition from analog to digital recordings. Changes and continuities reflected in the editorial policy (as read from the released recordings) served as a marker of different transitions happening at that time. KEYWORDS: transition; Yugoslavia; cultural policy; music industry; PGP–RTB / PGP–RTS; recordings; classical music During the twentieth century, the development of music industry inevitably influenced modes of the reception of music. -

Ana Petricevic Soprano

Ana Petricevic Soprano Ana Petricevic was born in Belgrade, Serbia, where she began her musical studies at the age of 8, when she started playing the flute. She studied opera singing at the University of Music in Belgrade. Her notable achievements as a student include winning the “Biserka Cvejic” award for the most promising young soprano and the “Danica Mastilovic” award for the best student. She also won the outright 1st prize (100/100 points) at the International Competition for Chamber Music “Davorin Jenko” and 2nd Prize at the International Competition for Opera Singers “Ondina Otta” in Maribor, Slovenia. and graduated with the highest grades, interpreting the roles of Micaela (Carmen, G. Bizet) and Tatiana (Eugene Onegin, P. I. Tchaikovsky). Ms Petricevic's professional debut was a success singing the role of Georgetta (Il Tabarro, G. Puccini) at the National Theatre of Belgrade. Following that performance, she made her debut also in the role of Contessa Almaviva (Le Nozze di Figaro, W. A. Mozart). In 2012 Ms Petricevic was presented a scholarship from the fund “Raina Kabaivanska” and, shortly afterwards, moved to Modena, Italy. For the next three years she studied with the famous Bulgarian soprano at the Institute of Music Vecchi-Tonelli di Modena. In this period, he sang in numerous concerts and prestigious events, the most prominent being the beneficiary Gala concert “Raina Kabaivanska presenta i Divi d'Opera” (2014, Sofia, Bulgaria). The concert was broadcasted live on National Television. After moving to Italy, Ms Petricevic attended different masterclasses, lead by renowned artists such as soprano Mariella Devia and baritone Renato Bruson. -

Iz Istorije Kulture I Arhitekture

Vladimir Mitrović Iz istorije kulture i arhitekture Zapisi jednog istraživača (1994−2014) Vladimir Mitrović • Iz istorije kulture i arhitekture MUZEJ SAVREMENE UMETNOSTI VOJVODINE Vladimir mitroViĆ IZ ISTORIJE KULTURE I ARHITEKTURE Zapisi jednog istražiVača (1994−2014) Aleksandar Kelemen Sadržaj: Uvodne napomene Iz istorije arhitekture XX veka Konkurs za gradnju pozorišta u Novom Sadu iz 1928/29. godine………………………….....…13 Primeri industrijske arhitekture novosadskih modernista………………………………........……21 Građevinarstvo i ekonomija između dva svetska rata……………………………………........……23 Arhitekta Juraj Najdhart i Novi Sad…………………………………………………………….........……….27 Prilog istoriji arhitekture socijalističkog šopinga: Samoposluga, robna kuća, buvljak, megamarket.….........................................................29 Staklo u novoj arhitekturi Bulevara oslobođenja u Novom Sadu: Zid i antizid………………….33 Novosadska arhitektura devedesetih godina: Kroz granje nebo……………………………………37 Efekat kanjona: O stambenoj izgradnji u Novom Sadu prvih godina nakon 2000……….45 Arhitektura u Vojvodini na početku XXI veka: Zaobilazne strategije………………………………47 Nova arhitektura porodičnih vila u Srbiji………………………………………………………….........….58 Kuća kao živa skulptura………………………………………………………………………...................………62 Arhitekta je (i) umetnik……………………………………………………………………..................………….65 Soliteri Srbije Prilozi za istoriju srpskih solitera (I): Život i smrt srpskih solitera - Potkivanje žabe….....73 Prilozi za istoriju srpskih solitera (II): Soliteri u ravnici…………………………………………….....78