Iran's Role in the South Caucasus and Caspian Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

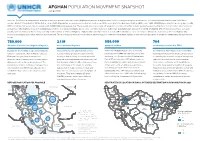

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Country Profile – Azerbaijan

Country profile – Azerbaijan Version 2008 Recommended citation: FAO. 2008. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Azerbaijan. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Water Policy Reforms in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia Achievements of the European Union Water Initiative, 2006-16 September 2016

Water Policy Reforms in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia Achievements of the European Union Water Initiative, 2006-16 September 2016 EUWI EU WATER INITIATIVE EECCA Foreword People’s wellbeing and economic development are increasingly dependent “Ten years after the EUWI upon water. Water scarcity is already a matter of daily struggle for more than launch, we are glad to 40 percent of people around the world. Our vulnerability to water stress is and will be more and more exacerbated by climate change. Improved water see more robust national governance is therefore crucial for accommodating a growing demand for policy frameworks, targeted water in the context of important scarcities. Without efforts to rethink and invesments and improved adjust the way we manage waters, an eventual water crisis will have daunting effects, including conflicts and forced migration. water management practices in countries of Eastern Europe, The European Commission has made water governance one of the priorities of its work, including in the context of international co-operation. The Caucasus and Central Asia.” European Union’s Water Initiative (EUWI), launched in 2006, has been an important avenue for sharing experience, addressing common challenges, and identifying opportunities that would enable our partners to meet water use demands in an environmentally sustainable manner. As part of its Neighbourhood and Development policies, the EU has closely involved the countries of Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia in this initiative. The EUWI has been a political undertaking that has helped participating countries improve their legislation in the water sector through the design and the implementation of national policy reforms. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

The North Caucasus Region As a Blind Spot in the “European Green Deal”: Energy Supply Security and Energy Superpower Russia

energies Article The North Caucasus Region as a Blind Spot in the “European Green Deal”: Energy Supply Security and Energy Superpower Russia José Antonio Peña-Ramos 1,* , Philipp Bagus 2 and Dmitri Amirov-Belova 3 1 Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Providencia 7500912, Chile 2 Department of Applied Economics I and History of Economic Institutions (and Moral Philosophy), Rey Juan Carlos University, 28032 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 3 Postgraduate Studies Centre, Pablo de Olavide University, 41013 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-657219669 Abstract: The “European Green Deal” has ambitious aims, such as net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. While the European Union aims to make its energies greener, Russia pursues power-goals based on its status as a geo-energy superpower. A successful “European Green Deal” would have the up-to-now underestimated geopolitical advantage of making the European Union less dependent on Russian hydrocarbons. In this article, we illustrate Russian power-politics and its geopolitical implications by analyzing the illustrative case of the North Caucasus, which has been traditionally a strategic region for Russia. The present article describes and analyses the impact of Russian intervention in the North Caucasian secessionist conflict since 1991 and its importance in terms of natural resources, especially hydrocarbons. The geopolitical power secured by Russia in the North Caucasian conflict has important implications for European Union’s energy supply security and could be regarded as a strong argument in favor of the “European Green Deal”. Keywords: North Caucasus; post-soviet conflicts; Russia; oil; natural gas; global economics and Citation: Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Bagus, P.; cross-cultural management; energy studies; renewable energies; energy markets; clean energies Amirov-Belova, D. -

Marat Grebennikov, Concordia University the Puzzle of a Loyal Minority: Why Do Azeris Support the Iranian State? Abstract Ever

Marat Grebennikov, Concordia University The Puzzle of a Loyal Minority: Why Do Azeris Support the Iranian State? Abstract Ever since its inception, the state of Iran has been pressed with the challenge of integrating the multiple ethnic identities that make up its plural society. Of a population exceeding 70 million, only 51% belongs to the Persian majority, while the single largest minority group are the Azeris numbering nearly 25 million (24%). In contrast to a number of other minorities like the Kurds and the Baluchis, the Azeris have shown loyalty to the Iranian state to the surprise of foreign scholars (Shaffer 2002, 2006). They have done so even in spite of a number of potentially favourable political and economic conditions that could support the realization of national aspirations. The paper addresses this puzzle: why, against seemingly favourable odds, Iranian Azeris have refrained from asserting their national ambitions and joining their newly independent kin north of the border? In an attempt to solve this puzzle, the paper will examine the triadic relationship among the Azeri minority in Iran, their home state (Iran), and their kin state (Azerbaijan). Although the Azeris constitute the titular majority in the Republic of Azerbaijan (91%), their articulation of national identity has diverged sharply from that of their kin brethren in Iran. Drawing on the works of Brubaker (2000, 2009), James (2001, 2006), Horowitz (1985), Saideman (2007, 2008) and Laitin (1998, 2007), the paper explores the hypothesis that the main reason for Azeri loyalty is the consistent and successful cooptation of the Azeri leadership into political and economic elite by the Iranian state. -

Iranian Influence in the South Caucasus and the Surrounding Region

IRANIAN INFLUENCE IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS AND THE SURROUNDING REGION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EUROPE AND EURASIA OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 5, 2012 Serial No. 112–192 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 77–164PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 16:38 Jan 03, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\EE\120512\77164 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey HOWARD L. BERMAN, California DAN BURTON, Indiana GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ELTON GALLEGLY, California ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois BRAD SHERMAN, California EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RON PAUL, Texas RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia CONNIE MACK, Florida THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska BEN CHANDLER, Kentucky MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas BRIAN HIGGINS, New York TED POE, Texas ALLYSON SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida CHRISTOPHER S. MURPHY, Connecticut JEAN SCHMIDT, Ohio FREDERICA WILSON, Florida BILL JOHNSON, Ohio KAREN BASS, California DAVID RIVERA, Florida WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MIKE KELLY, Pennsylvania DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TIM GRIFFIN, Arkansas TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina ANN MARIE BUERKLE, New York RENEE ELLMERS, North Carolina ROBERT TURNER, New York YLEEM D.S. -

Azerbaijan Democratic Party: Ups and Downs (1945-1946)

Revista Humanidades ISSN: 2215-3934 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Azerbaijan Democratic Party: Ups and Downs (1945-1946) Soleimani Amiri, PhD. Mohammad Azerbaijan Democratic Party: Ups and Downs (1945-1946) Revista Humanidades, vol. 10, no. 1, 2020 Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=498060395015 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/h.v10i1.39936 Todos los derechos reservados. Universidad de Costa Rica. Esta revista se encuentra licenciada con Creative Commons. Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Costa Rica. Correo electrónico: [email protected]/ Sitio web: http: //revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/humanidades This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative PhD. Mohammad Soleimani Amiri. Azerbaijan Democratic Party: Ups and Downs (1945-1946) Desde las ciencias sociales, la filosofía y la educación Azerbaijan Democratic Party: Ups and Downs (1945-1946) Partido Demócrata de Azerbaiyán: altibajos (1945-1946) PhD. Mohammad Soleimani Amiri DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/h.v10i1.39936 University of Sapienza, Italia Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=498060395015 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0554-6964 Received: 19 June 2019 Accepted: 23 November 2019 Abstract: Democratic Party of Azerbaijan's movement is one of the most important events in the history of Iran and the world. It was for the first time in the history of Iran that a political party seriously stressed the issue of autonomy. In addition, this movement as liberation movement prioritized several decisive and fundamental reform. -

From Oxus to Euphrates: the Sasanian Empire Speaker Profiles

From Oxus to Euphrates: The Sasanian Empire Speaker Profiles Dr. Ida Meftahi currently holds a Visiting Assistant Dr. Samra Elodie Azarnouche, is Associate Professorship in contemporary Iranian culture and Professor at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in society at the Roshan Institute for Persian Studies, Paris (PSL Research University Paris) where she teaches University of Maryland. She completed her doctoral the history of Zoroastrianism. Her research focuses on studies at the University of Toronto’s Department of Late Antiquity, Sasanian culture and religion, Iranian Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations and was a mythology and Middle Persian literature. Among her * postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for the Arts and publications are an edition of a Middle Persian text on Humanities at Pennsylvania State University. Her first book, Gender and Sasanian reali (Khosrow fils de Kawād et un page, 2013) and several Dance in Modern Iran: Biopolitics on Stage was released in May 2016 articles on rituals, priestly institutions, technical vocabulary, and (Routledge Iranian Studies Series). In addition to teaching Zoroastrian myths. interdisciplinary courses on Modern Iran, she is the director of the Lalehzar Digital Project, a component of the Roshan Initiative for Digital Dr. Touraj Daryaee, is a historian of ancient Iran, Humanities, as well as faculty advisor for Roshangar: Roshan apecializing on the Sasanian Empire. He is the author of Undergraduate Journal for Persian Studies. a number of books, including Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire, IB Tauris 2009; and The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History, OUP, 2012. He has also Dr. Stephen H. Rapp Jr., is Professor of Eurasian translated Middle Persian texts on the history of the and World History at Sam Houston State University. -

The Formation of Azerbaijani Collective Identity in Iran

Nationalities Papers ISSN: 0090-5992 (Print) 1465-3923 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cnap20 The formation of Azerbaijani collective identity in Iran Brenda Shaffer To cite this article: Brenda Shaffer (2000) The formation of Azerbaijani collective identity in Iran, Nationalities Papers, 28:3, 449-477, DOI: 10.1080/713687484 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713687484 Published online: 19 Aug 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 207 View related articles Citing articles: 5 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cnap20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 24 March 2016, At: 11:49 Nationalities Papers, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2000 THE FORMATION OF AZERBAIJANI COLLECTIVE IDENTITY IN IRAN Brenda Shaffer Iran is a multi-ethnic society in which approximately 50% of its citizens are of non-Persian origin, yet researchers commonly use the terms Persians and Iranians interchangeably, neglecting the supra-ethnic meaning of the term Iranian for many of the non-Persians in Iran. The largest minority ethnic group in Iran is the Azerbaijanis (comprising approximately a third of the population) and other major groups include the Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis and Turkmen.1 Iran’s ethnic groups are particularly susceptible to external manipulation and considerably subject to in uence from events taking place outside its borders, since most of the non-Persians are concen- trated in the frontier areas and have ties to co-ethnics in adjoining states, such as Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan and Iraq. -

Factors Influencing the Foreign Relations of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan

Annals of Global History Volume 1, Issue 2, 2019, PP 4-11 ISSN 2642-8172 Factors Influencing the Foreign Relations of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan Zahra Hosseinpour1, Majid Rafiei2, Abdolreza Alishahi3*, Atieh Mahdipour4 1Master's degree in Executive Master of Business Administration at Tehran University, Tehran, Iran 2Graduate Master of International Relations at Isfahan University, Isfahan, Iran 3Ph.D in Political Science at Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran 4Bachelor of Industrial Management, Islamic Azad University-South Tehran Branch (EN) *Corresponding Author: Abdolreza Alishahi, Ph.D in Political Science at Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT After the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the independence of the countries under its control, The Islamic Republic of Iran, on its northern borders, became neighbors with new countries. Azerbaijan is one of those countries that is located in the Caucasus region and declared independence on August 30, 1991, and the Islamic Republic of Iran recognized that country in the same year (1991) and established its relations with this country. During the years of the establishment of relations between the two countries, in spite of the religious and cultural commonalities, as well as the numerous opportunities and economic and security factors that could have exacerbated the interactions between the two sides, These relationships have been practically at a low level, and these joint factors not only did not increase interactions, but in some cases also led to conflicts and tensions between the two countries. According to the background, the question of this research is what factors influenced relations between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan? The hypothesis of this paper is that the factors affecting the relations between the two countries, Influenced by the negative attitudes of both countries towards each other and the involvement of transnational nations.