The Formation of Azerbaijani Collective Identity in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

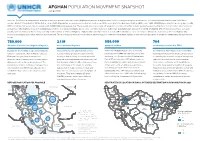

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty

KHAZAR UNIVERSITY Faculty: Education Major: General and Applied Linguistics Topic: “May your young people cast off the stone of singleness:” Azerbaijani “alqış phrases” (blessing formulas) and their American English equivalents, or what is revealed by the lack thereof Master student: Martha Lawry Scientific Advisor: Professor Hamlet Isaxanli Submitted January 2012 1 Summary This thesis by Martha Lawry is entitled “„may your young people cast off the stone of singleness:‟ Azerbaijani „alqış phrases‟ (blessing formulas) and their American English equivalents, or what is revealed by the lack thereof.” The objective of the research is to define the alqış phrases which are frequently used in modern spoken Azerbaijani, determine how best to define them in English, determine their linguistic functions in Azerbaijani, and compare them to the phrases that most closely fulfill the same functions in American English. Ethnographic and comparative research methods were used, including reviewing secondary sources (literature reviews) and qualitative research in the form of both semi- structured interviews conducted with native Azerbaijani speakers of varying ages and social strata living in the Azerbaijan Republic and open-ended structured interviews conducted via an online questionnaire with native English speakers living in the United States. The research led to the conclusion that alqış phrases should be defined as ―blessing formulas‖ in English. Most alqış phrases were determined to be grammatically distinguished by second or third person verbs in optative or imperative mood. They can have the expressive functions of being bono-recognitive, bono-petitive, malo-recognitive or malo-fugitive, although the most common are bono-petitive and malo-fugitive. Alqış phrases were also shown to be politeness strategies according to Levinson and Brown‘s politeness theory (used to protect the speaker‘s positive face or to protect the listener‘s negative face). -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology in the Caucasus

-.! r. d, J,,f ssaud Artsus^rNn Mlib scoIuswVC ffiLffi pac,^^€C erplJ pue lr{o) '-I dlllqd ,iq pa11pa ,(8oyoe er4lre Jo ecr] JeJd eq] pue 'sct1t1od 'tustleuolleN 6rl Se]tlJlljd 18q1 uueul lOu soop sltll'slstSo[ocPqJJu ul?lsl?JneJ leool '{uetuJO ezrsuqdtue ol qsl'\\ c'tl'laslno aql 1V cqtJo lr?JttrrJ Suteq e:u e,\\ 3llLl,\\'ieqt 'teqlout? ,{g eldoed .uorsso.rciclns euoJo .:etqSnr:1s louJr crleuols,{s eql ul llnseJ {eru leql tsr:d snolJes uoJl uPlseJnPJ lerll JO suoluolstp :o ..sSutpucJsltu,' "(rolsrqerd '..r8u,pn"r.. roJ EtlotlJr qsllqulso ol ]duralltl 3o elqetclecctl Surqsrn8urlstp o.1". 'speecorcl ll sV 'JB ,(rnluec qlxls-pltu eql ut SutuutSeq'et3:oe9 11^ly 'porred uralse,t\ ut uotJl?ztuolol {eer{) o1 saleleJ I se '{1:clncrlled lBJlsselc uP qil'\\ Alluclrol eq] roJ eJueptlc 1r:crSoloaeqcJe uuts11311l?J Jo uollRnlele -ouoJt-loueqlpue-snseon€JuJequoueqlpuE'l?luoulJv'er8rocg'uelteq -JaZVulpJosejotrolsrqerdsqtJoSuouE}erdlelutSutreptsuoc.,{11euor8ar lsrgSurpeeco:cl'lceistqlsulleJlsnlpselduexalere^esButlele;"{qsnsecne3 reded stql cql ur .{SoloeeqJlu Jo olnlpu lecrllod eql elBltsuotuop [lt,\\ .paluroclduslp lou st euo 'scrlr1od ,(:erodueluoJ o1 polelsJUtr '1tns:nd JturcpeJe olpl ue aq or ,{Soloeuqole 3o ecrlcu'rd eq} lcedxa lou plno'{\ 'SIJIUUOC aAISOldxe ouo 3Jor{,t\ PoJe uP sl 1t 'suolllpuoJ aseql IIe UsAtD sluqle pur: ,{poolq ,{11euor1dacxo lulo^es pue salndstp lelrollrrel snor0tunu qlr,n elalder uot,3e; elllBlo^ ,(re,r. e st 1l 'uolun lel^os JeuIJoJ aql io esdelloc eqt ue,tr.3 'snsBsnBJ aql jo seldoed peu'{u oql lle ro3 ln3Sutueau 'l?Iuusllllu -

Sheikh Safi Al-Din Ensemble in Ardabil

Weaver, M.E., Preliminary study on the conservation problems of five Iranian monuments, UNESCO, Paris, 1970. Sheikh Safi al-Din Ensemble in Weaver, M.E., Iran. The conservation of the Shrine of Sheik Safi Ardabil (Iran) at Ardabil: second preliminary study July-August 1971, No 1345 UNESCO, Paris, 1971. Technical Evaluation Mission: 18-22 October 2009 Additional information requested and received from the Official name as proposed by the State Party: State Party: A letter was sent to the State Party on 15 December 2009, requesting the following: Sheikh Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in Ardabil • Information about the timeframe for the approval and implementation of the Ardabil Master Plan; Location: • Description of how the provisions for the core, buffer, and landscape zones relate to the Master Province of Ardabil Plan; Islamic Republic of Iran • Further information on the structure and implementation of the Management Plan for the Brief description: nominated property; • Progress on the implementation without delay of The Sheik Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in ICHHTO’s plans to relocate the brick workshop; Ardabil was built as a microcosmic city of bazaars, public • Detailed information about the underground baths and squares, religious facilities, houses, and multi-level parking which is being built to the west offices. It was the largest khānegāh (Sufic place for of the museum and related measures to mitigate spiritual retreat) in Iran. During the reigns of the Safavid impact on the nominated property; rulers, this ensemble was of special political and national • Steps being taken to develop a Landscape Plan significance as the most prominent shrine of the founder for the entire nominated property; of the dynasty. -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

Oct. 6-12, 2020 Further Reproduction Or Distribution Is Subject to Original Copyright Restrictions

Weekly Media Report –Oct. 6-12, 2020 Further reproduction or distribution is subject to original copyright restrictions. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… EDUCATION: 1. Marine Corps’ Landmark PhD Program Celebrates First Technical Graduate (Marines.mil 7 Oct 20) (Navy.mil 7 Oct 20) (NPS.edu 7 Oct 20) (Military Spot 12 Oct 20) … Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Taylor Vencill When the Marine Corps developed its new Doctor of Philosophy Program (PHDP), the service recognized the need for a cohort of strategic thinkers and technical leaders capable of the applied research and innovative thinking necessary to develop warfighter advantage in the modern, cognitive age. The Technical version of the program, PHDP-T, just celebrated its first graduate, with Maj. Ezra Akin completing his doctorate in operations research from the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), Sept. 25. INDUSTRY PARTNERS: 2. Denver Startup Kayhan Space Lands $600k Seed Round for Collision Avoidance Software (ColoradoInno 6 Oct 20) … Nick Greenhalgh Much like on city streets, space traffic can be hectic and near misses are becoming all too common. Just last year, an in-orbit European Space Agency satellite was forced to perform an evasive maneuver to avoid a collision with a SpaceX satellite. Kayhan Space currently provides satellite collision assessment and avoidance support to the Naval Postgraduate School and BlackSky missions. FACULTY: 3. Will Armenia and Azerbaijan Fight to the Bitter End? [AUDIO INTERVIEW] (English News Highlights 5 Oct 20) Armenia and Azerbaijan accuse each other of attacking civilian areas as the deadliest fighting in the South Caucasus region for more than 25 years continues. KAN's Mark Weiss spoke with South Caucasus expert Brenda Shaffer, formerly a professor at Haifa University and now at the US Navy Postgraduate University. -

Situational Analysis of Visceral Leishmaniasis in the Most Important Endemic Area of the Disease in Iran

J Arthropod-Borne Dis, December 2017, 11(4): 482–496 E Moradi-Asl et al.: Situational Analysis of … Original Article Situational Analysis of Visceral Leishmaniasis in the Most Important Endemic Area of the Disease in Iran Eslam Moradi-Asl 1,2, *Ahmad Ali Hanafi-Bojd 1, *Yavar Rassi 1, Hassan Vatandoost 1,3, Mehdi Mohebali 4, Mohammad Reza Yaghoobi-Ershadi 1, Shahram Habibzadeh 5, Sadegh Hazrati 5, Sayena Rafizadeh 6 1Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Public Health, School of Public Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran 3Department of Chemical Pollutants and Pesticides, Institute for Environmental Research, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 4Department of Medical Parasitology and Mycology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 5Department of Infection Disease, School of Medicine, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran 6Ministry of Health and Medical Education, National Institute for Medical Research Development, Tehran, Iran (Received 26 Sep 2017; accepted 9 Dec 2017) Abstract Background: Visceral leishmaniasis is one of the most important vector borne diseases in the world, transmitted by sand flies. Despite efforts to prevent the spread of the disease, cases continue worldwide. In Iran, the disease usually occurs in children under 10 years. In the absence of timely diagnosis and treatment, the mortality rate is 95–100%. The main objective of this study was to determine the spatial and temporal distribution of visceral leishmaniasis as well as its correlation with climatic factors for determining high-risk areas in an endemic focus in northwestern Iran. -

Turkish Language in Iran (From the Ghaznavid Empire to the End of the Safavid Dynasty)

42 Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Turkish Language in Iran (from the Ghaznavid Empire to the end of the Safavid Dynasty) Zivar Huseynova Khazar University The history of Turks in Iran goes back to very ancient times, and there are differences of opinion among historians about the Turks‟ ruling of Iranian lands. However, all historians accept the rulers of the Turkish territories since the Ghaznavid Empire. In that era, Turks took over the rule of Iran and took the first steps toward broadening the empire. The Ghaznavi Turks, continuing to rule according to the local government system in Iran, expanded their territories as far as India. The warmongering Turks, making up the majority of the army, spread their own language among the army and even in the regions they occupied. Even if they did not make a strong influence in many cultural spheres, they did propagate their languages in comparison to Persian. Thus, we come across many Turkish words in Persian written texts of that period. This can be seen using the example of the word “amirakhurbashi” or “mirakhurbashı” which is composed of Arabic elements.1 The first word inside this compound word is the Arabic “amir” (command), but the second and third words composing it are Turkish. Amirakhurbashi was the name of a high government officer rank. Aside from this example, the Turkish words “çomaq”(“chomak”) and “qalachur”(“kalachur”) or “qarachur” (“karachur”) are used as names for military ammunition. 2 It is likely that the word karachur, which means a long and curved weapon, was taken from the word qılınc (“kilinj,” sword) and is even noted as a Turkish word in many dictionaries. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Fluoride Concentration of Drinking-Water of Qom, Iran

Iranian Journal of Health Sciences 2016; 4(1): 37-44 http://jhs.mazums.ac.ir Original Article Fluoride Concentration of Drinking-Water of Qom, Iran Ahmad Reza Yari 1 *Shahram Nazari 1 Amir Hossein Mahvi 2 Gharib Majidi 1, Soudabeh Alizadeh Matboo 3 Mehdi Fazlzadeh 3 1- Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran 2- Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 3- Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran *[email protected] (Received: 4 Jul 2015; Revised: 22 Oct 2015; Accepted: 27 Dec 2015) Abstract Background and Purpose: Fluoride is a natural element essential for human nutrition due to its benefits for dental enamel. It is well-documented that standard amounts of fluoride in drinking- water can decrease the rate of dental caries. This study was conducted with the aim of measuring fluoride concentration of drinking-water supplies and urban distribution system in Qom, Iran. Materials and Methods: Results were subsequently compared against national and international standards. All sources of drinking-water of rural and urban areas were examined. To measure fluoride, the standard SPADNS method and a DR/4000s spectrophotometer were used . Results: Results showed that the mean of fluoride concentration in rural areas, mainly supplied with groundwater sources, was 0.41 mg/L, that of the urban distribution system 0.82 mg/L, that of Ali-Abad station 0.11 mg/L, and that of the private water desalination system 0.24 mg/L. -

Hong Kong's Currency Board and Changing Monetary Regimes

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HONG KONG’S CURRENCY BOARD AND CHANGING MONETARY REGIMES Yum K. Kwan Francis T. Lui Working Paper 5723 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 1996 This paper was presented at NBER’s East Asian Seminar on Economics, and the NBER conference “Universities Research Conference on the Determination of Exchange Rates.” This work is part of NBER’s project on International Capital Flows which receives support from the Center for International Political Economy. We are grateful to the Center for International Political Economy for the support of this project and to Barry Eichengreen and Zhaoyong Zhang for helpful and constructive comments. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. O 1996 by Yum K. Kwan and Francis T. Lui. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including @ notice, is given to the source. NBER Working Paper 5723 August 1996 HONG KONG’S CURRENCY BOARD AND CHANGING MONETARY REGIMES ABSTRACT The paper discusses the historical background and institutional details of Hong Kong’s currency board. We argue that its experience provides a good opportunity to test the macroeconomic implications of the currency board regime. Using the method of Blanchard and Quah (1989), we show that the parameters of the structural equations and the characteristics of supply and demand shocks have significantly changed since adopting the regime. Variance decomposition and impulse response analyses indicate Hong Kong’s currency board is less susceptible to supply shocks, but demand shocks can cause greater short-term volatility under the system.