L&C Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lpl31t Cl1ato 1Io-Ob

LEWISANDCLARK AT LPL31T CL1ATO 1IO-OB -v A FORT CLATSOP 1805-06 WINTER QUARTERS OF LEWIS and CLARK EXPEDITION PUBLISHED BY THE CLATSOP COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop By LANCASTER POLLARD Oregon Historian Cover by ROLF KLEP (CopyrightClatsop County Historical Society) Published by CLATSOP COUNTY HiSTORICAL SOCIETY Printed by the SEASIDE PUBLISHING CO. Second Edition (RevIsed) 1962 Jntrodisctwn 1,j orerunnersofempire,Captains Meriwether Lewis and 1. William Clark holda unique place in American history and an even more unique place in the history of the Pacific North- west.The Lewis and Clark Expedition was the first official United States exploring expedition; perhaps themost important. These were the first American citizens tocross the con- tinent, the first to travel down the Snake and lower Columbia rivers.They were the first Americans to dwell in the only part of the American domain thatwas never the possession of another power.Spain. Russia, and Great Britain contested for its ownership, but the Oregon Countrycame direct to the United States from the Indian inhabitants.The expedition of Lewis and Clark contributed to that end, and helpedto add to the United States an area about halfas large as that of the original Thirteen States, thefirst American land on Pacific shores. Many books, large and small, by historians and novelists, have been published on the expedition, includingacentury after their tripthe original journals of Captains Lewis and Clark.In those books the expedition is viewed in thecourse of our national history, which then still centered on the Atlantic seaboard.In them the events at Fort Clatsop receive but brief treatment, although here was their goal, and, although their journey was only half completed, here theywere at their farthest point. -

OLD Toby'' Losr? REVISITING the BITTERROOT CROSSING

The L&C Journal's 10 most-used words --- Prince Maxmilian's journals reissued ...___ Lewis_ and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation I www.lewisandclark.org August2011 Volume 37, No. 3 W As ''OLD ToBY'' Losr? REVISITING THE BITTERROOT CROSSING How Blacksmiths Fed the L&C Expedition Prince Madoc, the Welsh, and the Mandan Indians Contents Letters: 10 most popular words in the L&C Journals 2 President's Message: Proceeding on from a challenging spring 4 Was Toby Lost? s Did the Shoshone guide take "a wrong road" over the Bitterroot Mountains, as Captain William Clark contended, or was Toby following a lesser-known Indian trail? By John Puckett Forging for Food 10 How blacksmiths of the Lewis and Clark Expedition saved the Corps from starvation during the winter of 1804-1805 at Fort Mandan By Shaina Robbins Was Toby Lost? p. 5 Prince Madoc and the Welsh Indians 16 When Lewis and Clark arrived at Fort Mandan President Jefferson suggested they look for a connection between the twelfth-century Welsh prince and the Mandan Indians. Did one exist? By Aaron Cobia Review Round-up ' 21 The first two volumes of newly edited and translated North American Journals of Prince Maximilian of Wjed; the story of Captain John McClallen, the fi~st _U f..S. officer to follow the expedition west in By Honor arid Right: How One Man Boldly Defined the D estiny of a Natio~ . Endnotes: The Stories Left Behind 24 The difficult task of picking the stories to tell and the stories to leave behind in the Montana's new history textbook Forging for Food, p. -

Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop: a Winter of Environmental Discomfort and Cultural Misunderstandings

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 7-9-1997 Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop: A winter of Environmental Discomfort and Cultural Misunderstandings Kirk Alan Garrison Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Garrison, Kirk Alan, "Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop: A winter of Environmental Discomfort and Cultural Misunderstandings" (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5394. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7267 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Kirk Alan Garrison for the Master of Arts in History were presented July 9, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: r DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: Go~do~ B. Dodds, Chair Department of History ********************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY on L?/M;< ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Kirk Alan Garrison for the Master of Arts in History, presented 9 July 1997. Title: Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop: A Winter of Environmental Discomfort and Cultural Misunderstandings. I\1embers of the Lewis and Clark expedition did not like the 1805-1806 winter they spent at Fort Clatsop near the mouth of the Columbia River among the Lower Chinookan Indians, for two reasons. -

Social Studies Extensions

Social Studies Extensions MISCELLANEOUS • Create a Timeline Bulletin Board or Flipbook. Assign each student one event and provide a template worksheet where they may create an illustration and caption the illustration to tell of a significant Expedition event. Use the “Lewis & Clark +200” exhibit timeline text or other timelines as resources. (E/M) • Read the “Profiles of the Kentucky Men in the Corps of Discovery” and complete the “Expedition Roster” worksheet. Discuss the various roles of individuals in the Corps of Discovery. What skills were important? How did they function as a team? If you were assembling an expedition team today, what kind of individuals would you recruit? Visit the National Geographic Web site for the Explorers in Residence program to learn about the skills that some of the world’s greatest explorers need today: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/council/eir/. (E/M) • Play the Kentucky State Fair’s interactive computer programs, “More than Nine Young Men from Kentucky” and “After the Expedition: More than Nine Young Men Epilogue,” now published on the Web at www.lewisandclark1803.com. • Open Response Question: (E/M) Lewis & Clark’s mission was to make new maps, meet with Indian nations, and record the plants, animals, and features of the new lands they explored. Your job is to plan the supplies to take on the Expedition. Choose three items that would help the party meet these three goals, one item for mapping, one for meeting Indians, and one for recording information about plants, animals, and land. Explain your answers. Next, list three important items for survival that could be found along the Trail (natural resources). -

Captain Meriwether Lewis's Branding Iron

Captain Meriwether Lewis's Branding Iron By Unknown Captain Meriwether Lewis carried this branding iron on the Corps of Discovery’s 1804–1806 exploration of western North America (the captains also carried a smaller "stirrup iron" used to brand horses). The details of this artifact’s manufacture are unknown, but historians have speculated that it might have been produced in 1804 at the armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, or perhaps by Private John Shields, a member of the Corps known for his iron-working skills. Lewis probably traded the iron to someone in the spring of 1806 near present-day The Dalles. In the 1890s, Hood River resident Linnaeus Winans found the iron on the north shore of the Columbia River near Memaloose Island. He gave the artifact to Philip L. Jackson, publisher of the Oregon Journal, who donated it to the Oregon Historical Society in 1941. Irons such as this one were too large for branding livestock and were usually used to mark wooden packing crates, barrels, and leather bags. Lewis’s iron was also used to mark trees as the members of the Corps made their way across the continent. In some cases, tree blazes functioned as property markers. When Expedition members stashed a pirogue on an island near the mouth of the Marias River on June 10, 1805, for example, Clark recorded that Lewis “branded several trees to prevent the Indians injureing her.” Expedition members carved their names into rocks and cliff faces on more than a dozen occasions, leaving a trail of what some historians have termed “graffiti.” Written by Cain Allen, 2004; revised 2021 Further Reading:Saindon, Bob. -

July 1979, Vol. 5 No. 3

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE LEWIS & CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 5 No. 3 July 1979 "Living History" at Fort Clatsop Timothy Walker, Richmond, Califor nia, (the exploring party's York) and Carol Jean Brafford,' Sacramento, California, (the Expedition's Saca gawea) are staff members at the Fort Clatsop National Memorial (near As toria, OR). On the occasion pictured above "Living History" was really in action. York and Sacagawea were The Expedition's journals frequently relate the activity of Cruzatte the fiddler. busy butchering and preparing deer On June 25, 1805, Captain Lewis' journal indicates that after preparations were meat, which was provided by the Ore completed to proceed on the next morning [we] "... were able to shake a foot gon State Game Commission. The . in dancing on the green to the music of the violin which Cruzatte plays deer had been killed by an automobile extremely well." (Thwaites, V. 2, p. 197). David Moffit, Portland, Oregon, a only hours before it was brought to member of the staff at the Fort Clatsop National Memorial (near Astoria, OR) the Memorial. Photograph by provides this "Living History" demonstration for visitors to the Memorial. He "Frenchy" Chuinard. is pictured above, in action, just outside of a squad room and in the parade I. Carol, an Oglala Sioux, was born on the ground at the replica of the exploring party's winter establishment. Photograph Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Oglala, by Roy J. Beadle. Shannon County, South Dakota. MEMBERS OF THE VALLEY COUNTY LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL SOCIETY INVITE YOU TO T HE ELEVENTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE FOUNDATION, AUGUST 12-15, 1979 GLASGOW, VALLEY COUNTY, MONTANA - SEE MAP ON PAGE 12 President Doumit's Message THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. -

Lewis & Clark – Indiana Connections

Lewis and Clark– Indiana Connections William Clark Meriwether Lewis Vincennes Clarksville Falls of the Ohio Louisville The Indiana Historian A Magazine Exploring Indiana History As the marker here indicates, the state of Indiana has an important, Focus recognized connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. That connection is being reinforced with a National Signature Event in Indiana Historical Bureau. Clarksville in October 2003. There is more to it than that, however. What many people forget is that until the party left its winter camp in May 1804, it remained in Indiana Territory, governed from Vincennes by William Henry Harrison. Harrison and Vincennes Marker is located at the Falls of the Ohio State Park, Clarksville, Clark County. were an important juncture for contact between the party and President Thomas Jefferson. Some core members of the Timeline references and other expedition party—the so-called “nine selected materials are intended to young men from Kentucky”—left enhance an understanding of the with the party from the Falls of the importance of the Falls of the Ohio Ohio, which referred to both area at the start and its part at the Kentucky and Indiana Territory end of the expedition. They are also across the Ohio River. The lives of intended to indicate the involvement Cover portraits: William Clark was these men—and their roles on the of Governor Harrison and Indiana painted by Charles Willson Peale, from life, expedition—are briefly reviewed in Territory—including the area that is 1807-1808. Meriwether Lewis was also the chart on pages 12-13. Some of now the State of Indiana—with the painted by Charles Willson Peale, from life, these men had personal, military, expedition. -

Appendices (PDF)

Appendices Appendix A: Background Information for the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................. 3 The Expedition: Making Ready ................................................................................................................................. 3 List of Supplies .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Timeline for the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................................................................. 9 Map of the Westward Route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................................ 19 Map of the Eastbound Route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................................ 20 The Expedition: Putting Away ................................................................................................................................ 21 Appendix B: People of the Lewis and Clark Expedition ....................................................................................... 23 President Thomas Jefferson ................................................................................................................................... 23 Captain Meriwether Lewis (Co-Leader) .................................................................................................................. 24 Seaman (Dog and Expedition -

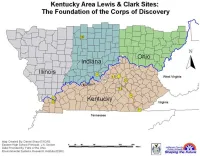

Corps Map.Pdf

Kentucky Area Lewis & Clark Sites: The Foundation of the Corps of Discovery 1. Maysville, KY—hometown of Private John Colter & a stop for Captain Lewis and his flotilla on 9/25/1803. 2. Cincinnati, OH—Lewis arrived 9/28/1803 and spent six days purchasing more supplies and meeting with Dr. William Goforth, a researcher of the fossil site across the river in Ky. 3. Big Bone Lick, KY—A famous fossil site, Lewis stayed 5 days and prepared a report for the President on the mammoth & other Ice Age creatures that could still roam out West. 4. Louisville—Clark met Lewis on 10/14/1803, and the Lewis & Clark Expedition began. The captains recruited the foundation of the Corps of Discovery & purchased supplies. 5. Clarksville, Indiana Territory—William Clark and York had just moved here from Louisville, and the cabin became a temporary headquarters for the Expedition. The keelboat and pirogue left the Falls of the Ohio on 10/26/1803. 6. Jefferson County—Several recruits were from this area. Reubin & Joseph Field and Nathaniel Pryor were living here in 1803, Charles Floyd was born here, and George Gibson settled here for a time after the Expedition. 7. Bullitt’s Lick—Reubin & Joseph Field, who were a part of the salt-making detail during the winter on the Pacific Ocean, learned the process at brother Ezekial’s salt works here. 8. Mercer County—Private Joseph Whitehouse was living here when recruited. 9. West Point—Blacksmith & gunsmith John Shields’ hometown. 10. Fort Massac, Illinois Territory—the Expedition recruited more men, including Joseph Whitehouse. -

Disembarkation

LESSON 1 Disembarkation Newspapers in Education is celebrating The Monumental Return of Lewis & Clark with Explore St. Louis in this four-part classroom series. FUN FACT #1: Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were asked by President Thomas Jefferson to explore and map the wild west of North America. They traveled the country to the Pacific Ocean, eventually returning to the Midwest. Watch Episode 1 – Disembarkation (explorestlouis.com/lewisandclark) ACTIVITY: After watching the video, students will learn about some of the people who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their incredible adventure. The expedition team is referred to as the Corps of Discovery. Students can use online and print resources to research the Corps and discover facts such as: • Age • Home state • Family • Education • Military rank • Why they were selected to be part of the expedition • Specific information about their role in the expedition ACTIVITY EXTENSION: Have students present a member of the Corps to the class individually or in small groups. Students can also write about each member of the team and this information can be made into a class book. WRITING CONNECTION: Would you have liked to be a member of the expedition party? Why or why not? CORPS OF DISCOVERY MEMBERS: • Meriwether Lewis • Robert Frazer • William Clark • Silas Goodrich • John Ordway • John Shields • Nathaniel Pryor • John Potts • Charles Floyd • Jean Baptiste LePage • Patrick Gass • John B. Thompson • William Bratton • Toussaint Charbonneau • John Collins • York (Clark’s slave) • John Colter • Sacajawea • Pierre Cruzatte • Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (son of Toussaint and Sacajawea) • Joseph Field • Seaman the Dog • Reuben Field For additional videos on Lewis and Clark, please visit STLtoday.com/NIE for a fun twist on their journey!. -

WPO August 2019

AUGUST 2019 VOL 45 NO 3 “When they shook hands, the Lewis and Clark Expedition began.” — Stephen Ambrose • The Trail Extends – Now 4,900 Miles • From Pittsburgh to the Pacific • The Significance of the Eastern Legacy • Another Great Book from Larry Morris The Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation (LCTHF) is pleased to make this edition of our quarterly journal, We Proceeded On (WPO), available to residents of the Falls of the Ohio area. This issue of WPO highlights the importance of the eastern portion of the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s travels to the success of the mission. LCTHF is a national membership organization. Our mission is to protect, preserve, and promote the Lewis and Clark Trail and its stories. Along with help from many friends in the Falls area and elsewhere, the advocacy LCTHF has maintained for a half-century resulted recently in the official eastward extension of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. From its previous eastern terminus at Wood River, IL, across from St. Louis, MO, the extension runs down the Mississippi River and then up the Ohio River to Pittsburgh, PA, adding 1,200 miles to form a nearly coast-to- coast trail of 4,900 miles. This extension also, at last, adds Indiana to the map of the National Scenic and Historic Trails administered by the National Park Service and the Forest Service, the final state that remained to be included. The Falls of the Ohio area played a large role in the expedition’s preparatory phase. At the Falls, Lewis and Clark shook hands and became a working team. -

THE ANZICK ARTIFACTS: a HIGH- TECHNOLOGY FORAGER TOOL ASSEMBLAGE Samuel Stockton White V

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2019 THE ANZICK ARTIFACTS: A HIGH- TECHNOLOGY FORAGER TOOL ASSEMBLAGE Samuel Stockton White V Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation White, Samuel Stockton V, "THE ANZICK ARTIFACTS: A HIGH-TECHNOLOGY FORAGER TOOL ASSEMBLAGE" (2019). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11338. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11338 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANZICK ARTIFACTS: A HIGH-TECHNOLOGY FORAGER TOOL ASSEMBLAGE By Samuel Stockton White V M.A. Anthropology, University of Montana, Missoula, Mt, 2019 Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2019 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Douglas H. MacDonald, Chair Anthropology Dr. Anna M. Prentiss Anthropology Dr. John Douglas Anthropology Dr. Thomas A. Foor Anthropology Dr. Steven D. Sheriff Geosciences i Acknowledgements This academic journey has been one of the most rewarding experiences in my life, taking me to amazing places such as the Yellowstone Backcountry and Chilean Patagonia. It all began for me as a boy following a passion for “arrowhead-hunting” on the shores of tributaries to the Chesapeake Bay.