U.S. Army Lewis and Clark Expedition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 1962 The

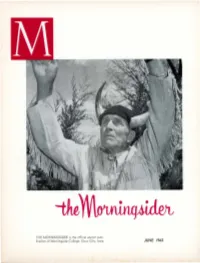

THE MORNINGSIDERis the official alumni publ- ication of Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa JUNE 1962 The President's Pen The North Iowa Annual Conference has just closed its 106th session. On the Cover Probably the most significant action of the Conference related to Morningside and Cornell. Ray Toothaker '03, as Medicine Man Greathealer, The Conference approved the plans for the pro raises his arms in supplication as he intones the chant. posed Conference-wide campaign, which will be conducted in 1963 for the amount of $1,500,000.00, "O Wakonda, Great Spirit of the Sioux, brood to be divided equally between the two colleges over this our annual council." and used by them in capital, or building programs. For 41 years, Mr. Toothaker lhas played the part of Greathealer in the ceremony initiating seniors into The Henry Meyer & Associates firm was em the "Tribe of the Sioux". ployed to direct the campaign. The cover picture was taken in one of the gardens Our own alumnus, Eddie McCracken, who is at Friendship Haven in Fort Dodge, Iowa, where Ray co-chairman of the committee directing the cam resides. Long a highly esteemed nurseryman in Sioux paign, was present at the Conference during the City, he laid out the gardens at Friendship Haven, first three critical days and did much in his work plans the arrangements and supervises their care. among laymen and ministers to assure their con His knowledge and love of trees, shrubs and flowers fidence in the program. He presented the official seems unlimited. It is a high privilege to walk in a statement to the Conference for action and spoke garden with him. -

George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West Mitchell Edward Pike Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West Mitchell Edward Pike Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Pike, Mitchell Edward, "George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 444. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/444 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE GEORGE DROUILLARD AND JOHN COLTER: HEROES OF THE AMERICAN WEST SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR LILY GEISMER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY MITCHELL EDWARD PIKE FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING/2012 APRIL 23, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..4 Chapter One. George Drouillard, Interpreter and Hunter………………………………..11 Chapter Two. John Colter, Trailblazer of the Fur Trade………………………………...28 Chapter 3. Problems with Second and Firsthand Histories……………………………....44 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….……55 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..58 Introduction The United States underwent a dramatic territorial change during the early part of the nineteenth century, paving the way for rapid exploration and expansion of the American West. On April 30, 1803 France and the United States signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty, causing the Louisiana Territory to transfer from French to United States control for the price of fifteen million dollars.1 The territorial acquisition was agreed upon by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Republic of France, and Robert R. Livingston and James Monroe, both of whom were acting on behalf of the United States. Monroe and Livingston only negotiated for New Orleans and the mouth of the Mississippi, but Napoleon in regard to the territory said “I renounce Louisiana. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling James Carpenter (Binghamton University) Abstract I challenge the traditional argument that Jefferson’s educational plans for Virginia were built on mod- ern democratic understandings. While containing some democratic features, especially for the founding decades, Jefferson’s concern was narrowly political, designed to ensure the survival of the new republic. The significance of this piece is to add to the more accurate portrayal of Jefferson’s impact on American institutions. Submit your own response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal.org/home Read responses to this article online http://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol21/iss2/5 ew historical figures have undergone as much advocate of public education in the early United States” (p. 280). scrutiny in the last two decades as has Thomas Heslep (1969) has suggested that Jefferson provided “a general Jefferson. His relationship with Sally Hemings, his statement on education in republican, or democratic society” views on Native Americans, his expansionist ideology and his (p. 113), without distinguishing between the two. Others have opted suppressionF of individual liberties are just some of the areas of specifically to connect his ideas to being democratic. Williams Jefferson’s life and thinking that historians and others have reexam- (1967) argued that Jefferson’s impact on our schools is pronounced ined (Finkelman, 1995; Gordon- Reed, 1997; Kaplan, 1998). because “democracy and education are interdependent” and But his views on education have been unchallenged. While his therefore with “education being necessary to its [democracy’s] reputation as a founding father of the American republic has been success, a successful democracy must provide it” (p. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/research/scholarly-editions-and-translations-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Institution: Princeton University Project Director: Barbara Bowen Oberg Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 318, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Statement of Significance and Impact of Project This project is preparing the authoritative edition of the correspondence and papers of Thomas Jefferson. Publication of the first volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson in 1950 kindled renewed interest in the nation’s documentary heritage and set new standards for the organization and presentation of historical documents. Its impact has been felt across the humanities, reaching not just scholars of American history, but undergraduate students, high school teachers, journalists, lawyers, and an interested, inquisitive American public. -

Qlocation of Legal Description Courthouse

Form NO to-30o <R«V 10-74) 6a2 « Great Explorers of the West: Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-6 UNITtDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Sergeant Floyd Monument AND/OR COMMON Sergeant Floyd Monument LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glenn Avenue and Louis Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Sioux City _J£VICINITY OF 006 faixthl STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 19 Woodbury 193 {{CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X_puBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILD ING<S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _?PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -3PES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: j ' m OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME (jSioux City Municipal Government) Mr. Paul Morris, Director Parks and Recreatl STREET & NUMBER Box 447, City Hall CITY. TOWN STATI Sioux City _ VICINITY OF Iowa 51102 QLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Wbodbury County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Sioux City Iowa REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE 1955 X.FEDERAL .....STATE _COUNTY ....LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic Sites Survey, 1100 L . Street, NW. CITY. TOWN Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE JCGOOD (surrounding RUINS .XALTERED MOVED DATE 1857 _FAIR area) _ UNEXPOSED x eroded x destroyed DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Sergeant Charles Floyd died August 20, 1804 and was buried on a bluff over looking the Missouri River from its northern bank. -

Lewis and Clark Trust a Friends Group for the Trail

JUNE 2013 A NEWSLETTER OF LEWIS anD CLARK NATIOnaL HISTORIC TRAIL Effective Wayshowing Pgs. 4-6 From the Superintendent Where is the Trail? What is the Trail? want to know. But then there are those who want to know exactly where the trail is…meaning where is the path that Lewis and Clark walked on to the Pacific? This is not such an easy question to answer. Part of the difficulty with this question is that with few exceptions we do not really know exactly where they walked. In many cases, some members of the expedition were Mark Weekley, Superintendent on the river in watercraft while others were on land at the same time. This question One of the interesting questions I get from is also problematic because it is often time to time is, “Where is the Trail?” This based in a lack of understanding of what a seems like an easy enough question to National Historic Trail is and how the Lewis answer. My first instinct is to hand someone and Clark expedition moved through the our brochure with a map of the trail on landscape. Some folks have an image of the back, or to simply say the trail runs Lewis and Clark walking down a path single from Wood River, Illinois, to the mouth of file with Sacajawea leading the way. To them the Columbia River on the Oregon Coast. it would seem that the National Historic Sometimes this seems to be all people Trail would be a narrow path which is well 2 defined. If a building or road has been built This raises the obvious question, “What is in this location then “the trail” is gone. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Lpl31t Cl1ato 1Io-Ob

LEWISANDCLARK AT LPL31T CL1ATO 1IO-OB -v A FORT CLATSOP 1805-06 WINTER QUARTERS OF LEWIS and CLARK EXPEDITION PUBLISHED BY THE CLATSOP COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Lewis and Clark at Fort Clatsop By LANCASTER POLLARD Oregon Historian Cover by ROLF KLEP (CopyrightClatsop County Historical Society) Published by CLATSOP COUNTY HiSTORICAL SOCIETY Printed by the SEASIDE PUBLISHING CO. Second Edition (RevIsed) 1962 Jntrodisctwn 1,j orerunnersofempire,Captains Meriwether Lewis and 1. William Clark holda unique place in American history and an even more unique place in the history of the Pacific North- west.The Lewis and Clark Expedition was the first official United States exploring expedition; perhaps themost important. These were the first American citizens tocross the con- tinent, the first to travel down the Snake and lower Columbia rivers.They were the first Americans to dwell in the only part of the American domain thatwas never the possession of another power.Spain. Russia, and Great Britain contested for its ownership, but the Oregon Countrycame direct to the United States from the Indian inhabitants.The expedition of Lewis and Clark contributed to that end, and helpedto add to the United States an area about halfas large as that of the original Thirteen States, thefirst American land on Pacific shores. Many books, large and small, by historians and novelists, have been published on the expedition, includingacentury after their tripthe original journals of Captains Lewis and Clark.In those books the expedition is viewed in thecourse of our national history, which then still centered on the Atlantic seaboard.In them the events at Fort Clatsop receive but brief treatment, although here was their goal, and, although their journey was only half completed, here theywere at their farthest point. -

Adams and Jefferson : Personal Politics in the Early Republic

d ADAMS AND JEFFERSON: Personal Politics in the Early Republic John Connor The deterioration of the friendship between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson remains a controversial subject among his torians. The two men were once the best of friends, spending personal time with each other’s family, and enjoying a profes sional collaboration that would become famous—drafting the Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, they freely ac knowledged their mutual fondness. In 1784, Adams wrote that his colleague Thomas Jefferson was “an old friend with whom I have often had occasion to labor at many a knotty problem and in whose ability and steadiness I always found great cause to confide.”1 Jefferson wrote similar words of praise to his friend James Madison: “[Adams] is profound in his views, and accurate in his judgments. He is so amiable, that I pronounce you will love him if ever you become acquainted with him.”2 But despite this initial close friendship, by the 1790s Adams called Jefferson “weak, confused, uninformed, and ignorant.”3 At the same time, Jefferson called Adams actions as President “the most grotesque scene in the tragiccomedy of govern ment.”4 What led these two men who once worked so closely together to turn from close friends to bitter enemies in only ten years? How their friendship dissolved has been discussed by Stephen Kurtz, Stanley Elkins, and Eric McKitrick, who em 58 phasize certain events in the Adams Presidency as precise mo ments in which the two men parted ways.5 Noble Cunningham Jr., points to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Act and the creation of a Standing Army as the point at which the two men’s differences became irreconcilable.6 Recent scholarship by James Sharp argues that a dinner conversation held before Adams was even elected led to their disbanding.7 A second school of thought, led by Merrill Peterson, Dumas Malone, and John Ferling, links the divide not so much to a particular event but to the actions of a third party, often Alexander Hamilton. -

Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- C

Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- c. 1839-1843) By William L. Lang Toussaint Charbonneau played a brief role in Oregon’s past as part of the Corps of Discovery, the historic expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1804-1806. He is one of the most recognizable among members of the Corps of Discovery, principally as the husband of Sacagawea and father of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, the infant who accompanied the expedition. The captains hired Charbonneau as an interpreter on April 7, 1805, at Fort Mandan in present-day North Dakota and severed his employment on August 17, 1806, on their return journey. Charbonneau was born on March 22, 1767, in Boucherville, Quebec, a present-day suburb of Montreal, to parents Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau and Marguerite Deniau. In his youth, he worked for the North West Company, and by the time Lewis and Clark encountered him in late 1804, he was an independent trader living at a Minnetaree village on the Knife River, a tributary to the Missouri near present-day Stanton, North Dakota. Charbonneau lived in the village with his Shoshoni wife Sacagawea, who had been captured by Hidatsas in present-day Idaho four years earlier and may have been sold to Charbonneau as a slave. On November 4, William Clark wrote in his journal that “a Mr. Chaubonée [Charbonneau], interpreter for the Gros Ventre nation Came to See us…this man wished to hire as an interpreter.” Lewis and Clark made a contract with him, but not with Sacagawea, although it is clear that the captains saw Sacagawea’s great benefit to the expedition, because she could aid them when they traveled through her former homeland. -

Field Notes7-2007#23.Pub

July 2007 Wisconsin’s Chapter ~ Interested & Involved Number 23 During this time in history: (July 4th, 1804/05/06) (The source for all Journal entries is, "The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedi- tion edited by Gary E. Moulton, The Uni- versity of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001.) By: Jack Schroeder July 4, 1804, (near today’s Atchison, Kan- sas) Clark: “Ushered in the day by a dis- charge of one shot from our bow piece, A worthwhile tradition was re- th proceeded on…Passed a creek 12 yards invigorated Saturday June 16 when wide…as this creek has no name, and this the Badger Chapter held a picnic for th being the 4 of July, the day of the inde- about 30 members and guests at the pendence of the U.S., we call it Independ- ence Creek…We closed the day by a dis- Horicon Marsh Environmental Educa- charge from our bow piece, an extra gill tion Barn. The location was widely of whiskey.” approved for the coolness of the inte- rior, the rustic feel of the stone walls, July 4, 1805, (at the Great Falls, Montana) Lewis: “Our work being at an end this and the sweeping view of the marsh. evening, (most men were working on the iron boat) we gave the men a drink of The potluck lunch featured four au- spirits, it being the last of our stock, and thentic Lewis and Clark recipes in- some of them appeared a little sensible of cluding a couple of bison dishes. The it’s effects. The fiddle was plied and they danced very merrily until 9 in the evening highlight of the meal was the two ta- when a heavy shower of rain put an end to bles groaning under the weight of that part of the amusement, though they dozens of excellent salads and des- continued their mirth with songs and fes- serts. -

Clarks Lookout State Park IEA Lesson Plan

A Collaborative Effort September 2006 Clark’s Lookout State Park Indian Education For All Lesson Plan Title People and Place: Understanding how human interaction with the land influences culture Content Area Geography Grade levels 9th-12th Duration 5 class periods Goals (Montana Standards/Essential Understandings) Social Studies Content Standard 3: Students apply geographic knowledge and skills (e.g., location, place, human/environment interactions, movement, and regions). Rationale: Students gain geographical perspectives on Montana and the world by studying the Earth and how people interact with places. Knowledge of geography helps students address cultural, economic, social, and civic implications of living in various environments. Benchmarks Students will: 4. Analyze how human settlement patterns create cooperation and conflict which influence the division and control of the Earth (e.g., treaties, economics, exploration, borders, religion, exploitation, water rights). 5. Select and apply appropriate geographic resources to analyze the interaction of physical and human systems (e.g., cultural patterns, demographics, unequal global distribution of resources) and their impact on environmental and societal changes. Essential Understanding 6: History is a story and most often related through the subjective experience of the teller. Histories are being rediscovered and revised. History told from an Indian perspective conflicts with what most of mainstream history tells us. Introduction Projecting above the dense cottonwoods and willows along the Beaverhead River, this rock outcropping provided an opportunity for members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition to view the route ahead. Captain William Clark climbed this hill overlooking the Beaverhead River to scout what lay ahead for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.