Flooding Across the Border a Review of UNHCR's Response to the Sudanese Refugee Emergency in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT in AREAS of RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT IN AREAS OF RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan CONTEXT ASSESSED LOCATION Renk Town is located in Renk County, Upper Nile State, near South Sudan’s border SUDAN Girbanat with Sudan. Since the formation of South Sudan in 2011, Renk Town has been a major Gerger ± MANYO Renk transit point for returnees from Sudan and, since the beginning of the current conflict in Wadakona 1 2013, for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing conflict in Upper Nile State. RENK Renk was classified by the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) Analysis Workshop El-Galhak Kurdit Umm Brabit in August 2019 as Phase 4 ‘Emergency’ with 50% of the population in either Phase 3 Nyik Marabat II 2 Kaka ‘Crisis’ (65,997 individuals) or Phase ‘4’ Emergency’ (28,284 individuals). Additionally, MELUT Renk was classified as Phase 5 ‘Extremely Critical’ for Global Acute Malnutrition MABAN (GAM),3 suggesting the prevalence of acute malnutrition was above the World Health Kumchuer Organisation (WHO) recommended emergency threshold with a recent REACH Multi- Suraya Hai Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA) establishing a GAM of above 30%.4 A measles Soma outbreak was declared in June 2019 and access to clean water was reportedly limited, as flagged by the Needs Analysis Working Group (NAWG) and by international NGOs 4 working on the ground. Hai Marabat I Based on the convergence of these factors causing high levels of humanitarian Emtitad Jedit Musefin need and the possibility for larger-scale returns coming to Renk County from Sudan, REACH conducted this Area-Based Assessment (ABA) in order to better understand White Hai Shati the humanitarian conditions in, and population movement dynamics to and from, Renk N e l Town. -

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack Table of Contents Page No. Table of Contents 1 State Map 2 Overview 3 Security and Political History 3 Major Conflicts 4 State Government Structure 6 Recovery and Development 7 State Resident Coordinator’s Support Office 8 Organizations Operating in the State 9-11 1 Map of Upper Nile State 2 Overview The state of Upper Nile has an area of 77,773 km2 and an estimated population of 964,353 (2009 population census). With Malakal as its capital, the state has 13 counties with Akoka being the most recent. Upper Nile shares borders with Southern Kordofan and Unity in the west, Ethiopia and Blue Nile in the east, Jonglei in the south, and White Nile in the north. The state has four main tribes: Shilluk (mainly in Panyikang, Fashoda and Manyo Counties), Dinka (dominant in Baliet, Akoka, Melut and Renk Counties), Jikany Nuer (in Nasir and Ulang Counties), Gajaak Nuer (in Longochuk and Maiwut), Berta (in Maban County), Burun (in Maban and Longochok Counties), Dajo in Longochuk County and Mabani in Maban County. Security and Political History Since inception of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), Upper Nile State has witnessed a challenging security and political environment, due to the fact that it was the only state in Southern Sudan that had a Governor from the National Congress Party (NCP). (The CPA called for at least one state in Southern Sudan to be given to the NCP.) There were basically three reasons why Upper Nile was selected amongst all the 10 states to accommodate the NCP’s slot in the CPA arrangements. -

Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advises the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project, supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state and county levels. The consultation process was led by the Government of South Sudan, with support from the Govern- ment of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photo: A senior chief from Upper Nile. © UNDP/Sun-ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword .......................................................................................................................... -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 Update)

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 update) Three months have elapsed since widespread conflict broke out in South Sudan, and Malakal, Upper Nile’s state capital, remains deserted and largely burned to the ground. The state is patchwork of zones of control, with the rebels holding the largely Nuer south (Longochuk, Maiwut, Nasir, and Ulang counties), and the government retaining the north (Renk), east (Maban and Melut), and the crucial areas around Upper Nile’s oil fields. The rest of the state is contested. The conflict in Upper Nile began as one between different factions within the SPLA but has now broadened to include the targeted ethnic killing of civilians by both sides. With the status of negotiations in Addis Ababa unclear, and the rebel’s 14 March decision to refuse a regional peacekeeping force, conflict in the state shows no sign of ending in the near future. With the first of the seasonal rains now beginning, humanitarian costs of ongoing conflict are likely to be substantial. Conflict began in Upper Nile on 24 December 2013, after a largely Nuer contingent of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLA) 7th division, under the command of General Gathoth Gatkuoth, declared their loyalty to former vice-president Riek Machar and clashed with government troops in Malakal. Fighting continued for three days. The central market was looted and shops set on fire. Clashes also occurred in Tunja (Panyikang county), Wanding (Nasir county), Ulang (Ulang county), and Kokpiet (Baliet county), as the SPLA’s 7th division fragmented, largely along ethnic lines, and clashed among themselves, and with armed civilians. -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State Describes Events Through 9 October 2014

The Conflict in Upper Nile State Describes events through 9 October 2014 On 9 May 2014 the Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS) and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) recommitted to the 23 January agreement on the cessation of hostilities. However, while the onset of the rainy season reduced the intensity of the conflict over the next four months, clashes continued. Neither side has established a decisive advantage. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) retains control of Malakal, the Upper Nile state capital, and much of the centre and west of the state. The period from May to August saw intermittent clashes around Nasir, as the SPLA-IO unsuccessfully attempted to recapture the town, which had been the centre of its recruitment drives during the first four months of the conflict. The main area of SPLA-IO operations is now around Wadakona in Manyo county, on the west bank of the Nile. In September rebels based in this area launched repeated assaults on Renk county near the GRSS’s sole remaining functioning oil field at Paloich. Oil production in Upper Nile was seriously reduced by clashes in February and March 2013, and stopped altogether in Unity state in December 2013. The SPLA increasingly struggles to pay its soldiers’ wages. On 6 September fighting broke out in the south of Malakal after soldiers commanded by Major General Johnson Olony, who had previously led the principally Shilluk South Sudan Defence Movement/Army, complained about unpaid wages. Members of the Abialang Dinka, who live close to Paloich, report that the SPLA is training 1,500 new recruits due to desertions and troops joining the rebels. -

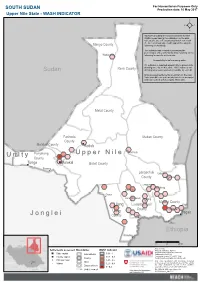

Jonglei Unity Upper Nile

For Humanitarian Purposes Only SOUTH SUDAN Production date: 10 May 2017 Upper Nile State - WASH INDICATOR REACH calculated the areas more likely to have WASH needs basing the estimation on the data collected between February and March 2017 with the Area of Knowledge (AoK) approach, using the Manyo County following methodology. The indicator was created by averaging the percentages of key informants (KIs) reporting on the Wadakona following for specific settlements: - Accessibility to safe drinking water 0% indicates a reported impossibility to access safe Renk County drinking water by all KIs, while 100% indicates safe Sudan drinking water was reported accessible by each KI. Only assessed settlements are shown on the map. Values for different settlements have been averaged and represented with hexagons 10km wide. Melut County Fashoda Maban County County Malakal County Kodok Panyikang Guel Guk Ogod U p p e r N i l e U n i t y County Tonga Malakal Baliet County Pakang Longochuk Udier County Chotbora Longuchok Mathiang Kiech Kon Dome Gum (Kierwan) Mading Maiwut County Ulang Luakpiny/Nasir Kigili County Maiwut Ulang Pagak J o n g l e i County Jikmir Jikou Ethiopia Wanding Sudan 0 25 50 km Data sources: Ethiopia Settlements assessed Boundaries WASH indicator Thematic indicators: REACH Administrative boundaries: UNOCHA; State capital International 0.81 - 1 Settlements: UNOCHA; County capital 0.61 - 0.8 Coordinate System:GCS WGS 1984 C.A.R. County Contact: [email protected] Principal town 0.41 - 0.6 Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Juba State Village 0.21 - 0.4 on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, Disputed area associates, donors or any other stakeholder D.R.C. -

South Sudan 2014 CHF Standard Allocation Project Proposal for CHF Funding Against Consolidated Appeal 2014

Document: SS CHF.SA.01 South Sudan 2014 CHF Standard Allocation Project Proposal for CHF funding against Consolidated Appeal 2014 For further CHF information please visit http://unocha.org/south-sudan/financing/common-humanitarian-fund or contact the CHF Technical Secretariat [email protected] SECTION I: CAP Cluster WASH CHF Cluster Priorities for 2014 First Round Standard Allocation Cluster Priority Activities for this CHF Round Cluster Geographic Priorities for this CHF Round Emergency water treatment units Twic County—Abyei preparation Rehabilitation of existing water points, where appropriate Wau, Malakal, Bentiu, Juba towns—Returnee Drilling/construction of new water points, if appropriate preparation/response Convert hand pumps to motorized boreholes with tap Pibor County—Early recovery activities in Pibor town, stands Gumuruk town, Boma town; or emergency response for Emergency communal latrines renewed conflict Distribution of hygiene kits Akobo and Uror Counties—Emergency response after Distribution of WASH NFIs renewed conflict, retaliation Emergency hygiene promotion training Nyirol,Ulang, Baliet—Sobat corridor Pre-positioning of core pipelines Maban County—Maban host community response Pre-positioning of affected Population pipeline supplies in Fashoda County—Kodok Maban and Yida Malakal County—ongoing response to stranded returnees Renk County—ongoing response to unresolved returnee needs Aweil East and Aweil North Counties—Mile 14 response Tonj South, Tonj East, Tonj North Counties—chronic WASH needs in an historically underserved area, affected most recently by floods Counties with high malnutrition verified by surveys that have been endorsed by nutrition cluster Any exceptional counties should be strongly justified SECTION II Project details The sections from this point onwards are to be filled by the organization requesting CHF funding. -

Displaced and Immiserated: the Shilluk of Upper Nile in South

Report September 2019 DISPLACED AND IMMISERATED The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19 Joshua Craze HSBA DISPLACED AND IMMISERATED The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19 Joshua Craze HSBA A publication of the Small Arms Survey’s Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan project with support from the US Department of State Credits Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, 2019 First published in September 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Coordinator, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Rebecca Bradshaw Fact-checker: Natacha Cornaz ([email protected]) Copy-editor: Hannah Austin ([email protected]) Proofreader: Stephanie Huitson ([email protected]) Cartography: Jillian Luff, MAPgrafix (www.mapgrafix.com) Design: Rick Jones ([email protected]) Layout: Frank Benno Junghanns ([email protected]) Cover photo: A man walks through the village of Aburoc, South Sudan, as an Ilyushin Il-76 flies over the village during a food drop as part of a joint WFP–UNICEF Rapid Response Mission on 13 May 2017. -

The Role of Livestock in Refugee–Host Community Relations

Humans and animals in refugee camps 71 FMR 58 June 2018 www.fmreview.org/economies be transmitted from animals to humans). But contribute to our understanding of the subject. those connections are not simply biomedical. We would welcome responses to this initial The art therapy work done in camps in Calais stage of our own project from practitioners and Nepal by a clinical psychotherapist in and researchers in any of the many and our network illustrates how much animals diverse fields which are of relevance. matter in the psychological and emotional Benjamin Thomas White health of humans. Precisely they matter how [email protected] will vary: in some places people believe University of Glasgow that ‘a home without a dog is just a house’, www.gla.ac.uk/schools/humanities/ while in others a dog in the home would 1. Herz M (Ed) (2012) From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the be not just unwelcome but an outrage. The Western Sahara, Lars Müller Publishers 302–303, 340–347 cultural significance of different animals 2. Rawlence B (2016) City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest will influence the psychological impact they Refugee Camp, Portobello Books have – and it will also affect, and be affected 3. International Union for the Conservation of Nature (2018) by, their role in refugees’ social and economic Survey Report on Elephant Movement, Human-Elephant Conflict Situation, and Possible Intervention Sites in and around Kutupalong lives. This in turn will inform the ways in Camp, Cox’s Bazar www.unhcr.org/5a9946a34 which refugees organise (or reorganise) 4. -

Master Thesis Impact Assessment of Oil Exploitation in Upper Nile State

Master Thesis im Rahmen des Universitätslehrganges „Geographical Information Science & Systems“ (UNIGIS MSc) am Interfakultären Fachbereich für GeoInformatik (Z_GIS) der Paris Lodron‐Universität Salzburg zum Thema Impact assessment of oil exploitation in Upper Nile State, South Sudan, using multi‐temporal Landsat data vorgelegt von Alexander Mager U1532, UNIGIS MSc Jahrgang 2011 Zur Erlangung des Grades „Master of Science (Geographical Information Science and Systems) – MSc (GIS)“ Gutachter: Ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Josef Strobl Gilching, 07.08.2013 Acknowledgements This study was carried out in cooperation between Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC) and the Department GeoRisks and Civil Security of the German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD) of the German Aerospace Center (DLR). I would like to thank Elisabeth Schöpfer, Kristin Spröhnle, Stella Hubert, Lars Wirkus, Elke Graewert and Lena Guesnet for their support, advice and patience. Thanks to Fabian Selg for preceding work which was of great benefit. Martin Petry provided great maps and shared valuable information for which I am grateful. A very special thank you goes to Elmar Csaplovics for digging up Harrison and Jackson’s 1958 classic study on the ecology of Sudan. I was deeply impressed and I am very grateful for his kind act. I Erklärung “Ich versichere, dass ich die beiliegende Diplomarbeit ohne Hilfe Dritter und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel angefertigt und die den benutzten Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Diese Arbeit hat in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch keiner Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegen.“ Gilching, den 07.08.2013 II Abstract This study examined the spatial impacts of oil exploitation in Melut County, South Sudan, at six points in time between 1999 and 2011. -

SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE, 68 29 June – 03 July 2015 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS

SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE, 68 29 June – 03 July 2015 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS 731,675 South Sudanese Refugees (total) According to the latest report from the Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 28 June, 396 cholera cases, including 26 600,758 deaths, had been reported in Juba County. Interviews with patients admitted New arrivals (since 15 Dec. 2013) to Juba Teaching Hospital with cholera have revealed knowledge gaps on how the disease is spread. Humanitarian partners called for improved access to safe drinking water, latrine use and good personal and food hygiene. 130,917 Old caseload before 15 Dec. 2013 The consultative meeting between the former Vice-President and leader of (covered by the regular budget) the Opposition, Mr. Riek Machar, and the President, Mr. Salva Kiir, hosted by the Kenyan President Mr. Uhuru Kenyatta on 27 June 2015 has not achieved 264,848 any breakthrough. The agenda for the meeting included discussions on Refugees in South Sudan contentious points of the recent IGAD proposal including questions of power- sharing, federalism and compensation for victims of the conflict. 1.5 M According to the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), on 1 July Internally Displaced People (IDPs) three members of forces belonging to either the Sudan People’s Liberation Army In Opposition or the allied militia led by General Johnson Olony, who are currently controlling Malakal (Upper Nile State), opened fire on IDPs at a recently opened Protection of Civilians (POC) site in the UNMISS compound. BUDGET: USD 779.4 M One civilian was killed and six IDPs were wounded. -

5.6 Disaster Preparedness and Resilience

Disasters, Conflict, KNOWLEDGE NOTE Public Disclosure Authorized and Displacement Intersectional Risks in South Sudan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of the World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The term ‘disaster’ in this publication refers to events caused by natural hazards. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because the World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected] Cover page: A community in Ulang County (Upper Nile State) affected by seasonal flooding in 2019. Photograph taken by the Shelter and Non Food Items (SNFI) team during flood response (09 October 2019).