Understanding Host-Refugee Tensions in Maban County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE to SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13 UPPER NILE SUDAN WARRAP ACTED Solidarités ACTED CRS World ABYEI AREA Renk Vision GOAL Food for SOUTH SUDAN CRS SC the Hungry ACTED MENTOR UNITY FAO UNDP GOAL DRC NRC CARE Global Communities/CHF UNFPA Medair IOM UNOPS Mercy Corps GOAL UNICEF MENTOR RI WCDO MENTOR Mercy Corps UNMAS RI World IOM Paloich OCHA WHO Vision SouthSouth Sudan-SudanSudan-Sudan boundaryboundary representsrepresents JanuaryJanuary 1,1, 19561956 alignment;alignment; finalfinal alignmentalignment pendingpending ABYEI AREA * UPPER NILE negotiationsnegotiations andand demarcation.demarcation. Abyei ETHIOPIA Malakal Abanima SOUTH SUDAN-WIDE Bentiu Nagdiar Warawar JONGLEI FAO Agok Yargot ACTED IOM WESTERN BAHR Malualkon NORTHERN UNITY EL GHAZAL Aweil Khorflus Nasir CRS Medair BAHR Pagak WARRAP Food for OCHA Raja EL GHAZAL the Hungry UNICEF Fathay Walgak BAHR EL GHAZAL IMC Akobo WFP Adeso MENTOR Wau WHO Tearfund PACT SOUTH SUDAN JONGLEI UNICEF UMCOR Pochalla World WFP Vision Welthungerhilfe Rumbek ICRC LAKES UNHCR CENTRAL Wulu Mapuordit AFRICAN Akot Bor Domoloto Minkamman REPUBLIC PROGRAM KEY Tambura Amadi USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Kaltok WESTERN EQUATORIA EASTERN EQUATORIA Agriculture and Food Security Livelihoods Juba Kapoeta Economic Recovery and Market Logistics and Relief Commodities Systems Yambio Multi-Sectoral Assistance CENTRAL Education EQUATORIA Torit Nagishot Nutrition EQUATORIA Gender-based Birisi ARC Violence Prevention Protection Ye i CHF Health Risk Management Policy and Practice KENYA -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

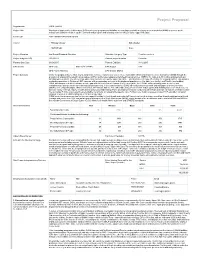

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT in AREAS of RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT IN AREAS OF RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan CONTEXT ASSESSED LOCATION Renk Town is located in Renk County, Upper Nile State, near South Sudan’s border SUDAN Girbanat with Sudan. Since the formation of South Sudan in 2011, Renk Town has been a major Gerger ± MANYO Renk transit point for returnees from Sudan and, since the beginning of the current conflict in Wadakona 1 2013, for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing conflict in Upper Nile State. RENK Renk was classified by the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) Analysis Workshop El-Galhak Kurdit Umm Brabit in August 2019 as Phase 4 ‘Emergency’ with 50% of the population in either Phase 3 Nyik Marabat II 2 Kaka ‘Crisis’ (65,997 individuals) or Phase ‘4’ Emergency’ (28,284 individuals). Additionally, MELUT Renk was classified as Phase 5 ‘Extremely Critical’ for Global Acute Malnutrition MABAN (GAM),3 suggesting the prevalence of acute malnutrition was above the World Health Kumchuer Organisation (WHO) recommended emergency threshold with a recent REACH Multi- Suraya Hai Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA) establishing a GAM of above 30%.4 A measles Soma outbreak was declared in June 2019 and access to clean water was reportedly limited, as flagged by the Needs Analysis Working Group (NAWG) and by international NGOs 4 working on the ground. Hai Marabat I Based on the convergence of these factors causing high levels of humanitarian Emtitad Jedit Musefin need and the possibility for larger-scale returns coming to Renk County from Sudan, REACH conducted this Area-Based Assessment (ABA) in order to better understand White Hai Shati the humanitarian conditions in, and population movement dynamics to and from, Renk N e l Town. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

South Sudan SITUATION REPORT 4 June 2015

South Sudan SITUATION REPORT 4 June 2015 South Rich .org> unicef Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report UNICEF/2015/South Sudan/ UNICEF/2015/South AgotAgot<rmatema@ © 22 MAY – 4 JUNE 2015: SOUTH SUDAN SITREP #60 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.52 million People internally displaced since 15 The recent intensification of conflict has continued to take a heavy toll on December 2013 children with a total of 161 incidents of grave child rights violations (OCHA, Humanitarian Bulletin dated 29 May, 2015) reported this year, 84 of which have been reported from Unity State in May alone. This includes the verified killing of 95 children and unverified 812,816* reports of large scale use of children by the all sides to the conflict. Estimated internally displaced children Unverified reports of similar grave child rights violations have been under 18 years reported in Upper Nile State. Outside South Sudan There are eight suspected and one confirmed cholera case in Juba, seven of which are in Juba Protection of Civilians (PoC) site. UNICEF, WHO and 552,231 Cluster and implementing partners are working to increase prevention Estimated new South Sudanese refugees in and response interventions. neighbouring countries since 15 December 2013 (OCHA, Humanitarian Bulletin dated 29 May, 2015) The latest Interagency Phase Classification (IPC) results were released on 27 May, with nearly 248,000 children estimated to be suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Child malnutrition rates remain above Priority Humanitarian Funding needs the emergency threshold of 15 per cent in both conflict-affected and high- January - December 2015 burden states of Greater Upper Nile, Warrap and Northern Bahr el Ghazal. -

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack Table of Contents Page No. Table of Contents 1 State Map 2 Overview 3 Security and Political History 3 Major Conflicts 4 State Government Structure 6 Recovery and Development 7 State Resident Coordinator’s Support Office 8 Organizations Operating in the State 9-11 1 Map of Upper Nile State 2 Overview The state of Upper Nile has an area of 77,773 km2 and an estimated population of 964,353 (2009 population census). With Malakal as its capital, the state has 13 counties with Akoka being the most recent. Upper Nile shares borders with Southern Kordofan and Unity in the west, Ethiopia and Blue Nile in the east, Jonglei in the south, and White Nile in the north. The state has four main tribes: Shilluk (mainly in Panyikang, Fashoda and Manyo Counties), Dinka (dominant in Baliet, Akoka, Melut and Renk Counties), Jikany Nuer (in Nasir and Ulang Counties), Gajaak Nuer (in Longochuk and Maiwut), Berta (in Maban County), Burun (in Maban and Longochok Counties), Dajo in Longochuk County and Mabani in Maban County. Security and Political History Since inception of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), Upper Nile State has witnessed a challenging security and political environment, due to the fact that it was the only state in Southern Sudan that had a Governor from the National Congress Party (NCP). (The CPA called for at least one state in Southern Sudan to be given to the NCP.) There were basically three reasons why Upper Nile was selected amongst all the 10 states to accommodate the NCP’s slot in the CPA arrangements. -

UPPER NILE Yaa

SOUTH SUDAN Maban County reference map SUDAN ETHIOPIA Renk CAR DRC KENYA El Haragis UGANDA Khantioq Wakhlet Waqfet Kaddah Dema Hawaga Zurzur Kudda Korpar Zarzor Es Sida Ban Kaala Abu Khamirah Al Amin SUDAN Ban Burka Dar As Saqiyah Ban Tami Sa`dan Wad Tabir Dudu Ban Yaawin Jantoka Ballilah Derib Jungara Abu Daqn Guffa Ban Toltukke Mardi Abu Diqn Nushur Dinka Degeis Danga Kagyana Aqordit Harbi Cholei Sheikh Bade Ban Tollog Melut Abd Er Rigal Khawr Tunbak Awag El Bagar Banwiir Jemaam Faraj Allah A Tunguls Dhomat Nyeda Fadlull Alkedwa Junguls Nyanya Bumma Junquator Byam Bendingo Falakah Abu Kot Nurah Kunjila Kaya Dido Dzhantoqa Yusuf Natcha Nila Feyqa Tuyo Quffah Adar Kaluang Kanshur Bankeka Ukka Kanje Yelqu Feika Tagga Makajiongo Yusuf Batil Bir Talta Gendrassa Bang Allah Jabu Qadiga Bunj Agyagya Ballah Dinga Marinja Tumma Kannah Liti Gumma Khadiga Maban Dima Dangaji Baliet Nyang Ghanga Liang UPPER NILE Yaa Tungyu Keiwa Maundi Bella Bugaya Deingo Chidu Beneshowa Abmju Moibar Swamp Sonca Boac International boundary State boundary County boundary Undetermined boundary Abyei region Country capital Longochuk Administrative centre/County capital Principal town Secondary town Chotbora Village Primary road Luakpiny/NasirSecondary road Tertiary road Main river 0 5 10 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of Abyei area is not yet determined. Created: March 2020 | Code: SS-7105 | Sources: OCHA, SSNBS | Feedback: [email protected] | unocha.org/south-sudan | reliefweb.int/country/ssd | southsudan.humanitarianresponse.info . -

Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advises the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project, supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state and county levels. The consultation process was led by the Government of South Sudan, with support from the Govern- ment of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photo: A senior chief from Upper Nile. © UNDP/Sun-ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword .......................................................................................................................... -

South Sudan Crisis Situation Report 59 As of 23 Octobertg.Indd

South Sudan Crisis Situation Report No. 59 (as of 23 October 2014) This report was produced by OCHA South Sudan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 17 to 23 October. The next report will be issued on or around 31 October 2014. Highlights ● As of October, aid organizations had reached 3.5 million of the 3.8 million people to be assisted in 2014, though the response needed to be sustained. ● Heavy rains in the past two weeks have caused fl ooding in the displacement sites in Mingkaman, Lakes State. ● Biometric registration was underway in Malakal, Upper Nile State, with 10,000 people in the new and improved Protection of Civilians site registered to date. ● The whereabouts of a humanitarian staff abducted in Malakal on 16 October were still unknown, despite calls for his immediate release. 3.8 million 3.5 million 1.4 million 469,000 People to be assisted by the end People reached with People internally displaced by People have fl ed to of the year humanitarian assistance* violence neighboring countries * This includes people internally displaced, refugees from other countries sheltering in South Sudan and other vulnerable communities who have received assistance since January 2014. This does not imply that the needs of these people have been comprehensively met. Situation overview The security situation remained largely stable during the week, though tension remained high in Bentiu and Malakal towns. On 16 October, an aid worker was abducted by armed elements from the airfi eld in Malakal. The staff member’s whereabouts and condition is unknown at the time of reporting. -

Interagency Assessment in Melut – 30 May to 01 June 2015

Interagency Assessment in Melut – 30 May to 01 June 2015 A mission was conducted in Melut from 30 May 2015 until 1 June 2015 to assess the conditions of the IDPs and host communities in Melut County after the conflict. The agencies and partners participating in this assessment included UNHCR, UNICEF, GOAL and IMA. The purpose of this assessment mission was: Visiting IDPs in all sites of Melut County i.e. Dinthoma I, Dinthoma II, POCs, Hai Soma and Paloich. To assess and determine the immediate response required for IDPs in terms of their needs and protection. Recommendations of actions needed to be undertaken immediately following the conflict. To assess the feasibility of the return of humanitarian organizations back to Melut to resume operations, pending normalization of the security situation. Background Heavy fighting erupted in the town of Melut in Upper Nile on 19 May, killing at least six internally displaced persons, leaving several wounded. More than 20,000 civilians sheltering in Dehtoma I and II displacement sites near the UN base in Melut dispersed to Paloich and Renk. Aid agencies relocated out of the town leaving only critical staff to meet life-saving needs of the remaining displaced people. Over 1,600 displaced people were reportedly sheltering in the UN Mission base in Melut1. During the conflict, a total of 279 HHS/1,177 individuals (from Shilluk, Dinka, Nuer and other foreign nationalities) were registered and issued with temporary WFP tokens within the UNMISS CSB compound. NFIs, including plastic sheeting, were issued to the IDPs for emergency shelte. 10 HHs whose houses were burnt by shelling which landed in PoC 1 were registered and will be prioritized with NFIs package assistance.