Kala-Azar Epidemiology and Control, Southern Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT in AREAS of RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT IN AREAS OF RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan CONTEXT ASSESSED LOCATION Renk Town is located in Renk County, Upper Nile State, near South Sudan’s border SUDAN Girbanat with Sudan. Since the formation of South Sudan in 2011, Renk Town has been a major Gerger ± MANYO Renk transit point for returnees from Sudan and, since the beginning of the current conflict in Wadakona 1 2013, for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing conflict in Upper Nile State. RENK Renk was classified by the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) Analysis Workshop El-Galhak Kurdit Umm Brabit in August 2019 as Phase 4 ‘Emergency’ with 50% of the population in either Phase 3 Nyik Marabat II 2 Kaka ‘Crisis’ (65,997 individuals) or Phase ‘4’ Emergency’ (28,284 individuals). Additionally, MELUT Renk was classified as Phase 5 ‘Extremely Critical’ for Global Acute Malnutrition MABAN (GAM),3 suggesting the prevalence of acute malnutrition was above the World Health Kumchuer Organisation (WHO) recommended emergency threshold with a recent REACH Multi- Suraya Hai Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA) establishing a GAM of above 30%.4 A measles Soma outbreak was declared in June 2019 and access to clean water was reportedly limited, as flagged by the Needs Analysis Working Group (NAWG) and by international NGOs 4 working on the ground. Hai Marabat I Based on the convergence of these factors causing high levels of humanitarian Emtitad Jedit Musefin need and the possibility for larger-scale returns coming to Renk County from Sudan, REACH conducted this Area-Based Assessment (ABA) in order to better understand White Hai Shati the humanitarian conditions in, and population movement dynamics to and from, Renk N e l Town. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

UPPER NILE Yaa

SOUTH SUDAN Maban County reference map SUDAN ETHIOPIA Renk CAR DRC KENYA El Haragis UGANDA Khantioq Wakhlet Waqfet Kaddah Dema Hawaga Zurzur Kudda Korpar Zarzor Es Sida Ban Kaala Abu Khamirah Al Amin SUDAN Ban Burka Dar As Saqiyah Ban Tami Sa`dan Wad Tabir Dudu Ban Yaawin Jantoka Ballilah Derib Jungara Abu Daqn Guffa Ban Toltukke Mardi Abu Diqn Nushur Dinka Degeis Danga Kagyana Aqordit Harbi Cholei Sheikh Bade Ban Tollog Melut Abd Er Rigal Khawr Tunbak Awag El Bagar Banwiir Jemaam Faraj Allah A Tunguls Dhomat Nyeda Fadlull Alkedwa Junguls Nyanya Bumma Junquator Byam Bendingo Falakah Abu Kot Nurah Kunjila Kaya Dido Dzhantoqa Yusuf Natcha Nila Feyqa Tuyo Quffah Adar Kaluang Kanshur Bankeka Ukka Kanje Yelqu Feika Tagga Makajiongo Yusuf Batil Bir Talta Gendrassa Bang Allah Jabu Qadiga Bunj Agyagya Ballah Dinga Marinja Tumma Kannah Liti Gumma Khadiga Maban Dima Dangaji Baliet Nyang Ghanga Liang UPPER NILE Yaa Tungyu Keiwa Maundi Bella Bugaya Deingo Chidu Beneshowa Abmju Moibar Swamp Sonca Boac International boundary State boundary County boundary Undetermined boundary Abyei region Country capital Longochuk Administrative centre/County capital Principal town Secondary town Chotbora Village Primary road Luakpiny/NasirSecondary road Tertiary road Main river 0 5 10 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of Abyei area is not yet determined. Created: March 2020 | Code: SS-7105 | Sources: OCHA, SSNBS | Feedback: [email protected] | unocha.org/south-sudan | reliefweb.int/country/ssd | southsudan.humanitarianresponse.info . -

Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advises the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project, supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state and county levels. The consultation process was led by the Government of South Sudan, with support from the Govern- ment of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photo: A senior chief from Upper Nile. © UNDP/Sun-ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword .......................................................................................................................... -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 Update)

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 update) Three months have elapsed since widespread conflict broke out in South Sudan, and Malakal, Upper Nile’s state capital, remains deserted and largely burned to the ground. The state is patchwork of zones of control, with the rebels holding the largely Nuer south (Longochuk, Maiwut, Nasir, and Ulang counties), and the government retaining the north (Renk), east (Maban and Melut), and the crucial areas around Upper Nile’s oil fields. The rest of the state is contested. The conflict in Upper Nile began as one between different factions within the SPLA but has now broadened to include the targeted ethnic killing of civilians by both sides. With the status of negotiations in Addis Ababa unclear, and the rebel’s 14 March decision to refuse a regional peacekeeping force, conflict in the state shows no sign of ending in the near future. With the first of the seasonal rains now beginning, humanitarian costs of ongoing conflict are likely to be substantial. Conflict began in Upper Nile on 24 December 2013, after a largely Nuer contingent of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLA) 7th division, under the command of General Gathoth Gatkuoth, declared their loyalty to former vice-president Riek Machar and clashed with government troops in Malakal. Fighting continued for three days. The central market was looted and shops set on fire. Clashes also occurred in Tunja (Panyikang county), Wanding (Nasir county), Ulang (Ulang county), and Kokpiet (Baliet county), as the SPLA’s 7th division fragmented, largely along ethnic lines, and clashed among themselves, and with armed civilians. -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State Describes Events Through 9 October 2014

The Conflict in Upper Nile State Describes events through 9 October 2014 On 9 May 2014 the Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS) and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) recommitted to the 23 January agreement on the cessation of hostilities. However, while the onset of the rainy season reduced the intensity of the conflict over the next four months, clashes continued. Neither side has established a decisive advantage. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) retains control of Malakal, the Upper Nile state capital, and much of the centre and west of the state. The period from May to August saw intermittent clashes around Nasir, as the SPLA-IO unsuccessfully attempted to recapture the town, which had been the centre of its recruitment drives during the first four months of the conflict. The main area of SPLA-IO operations is now around Wadakona in Manyo county, on the west bank of the Nile. In September rebels based in this area launched repeated assaults on Renk county near the GRSS’s sole remaining functioning oil field at Paloich. Oil production in Upper Nile was seriously reduced by clashes in February and March 2013, and stopped altogether in Unity state in December 2013. The SPLA increasingly struggles to pay its soldiers’ wages. On 6 September fighting broke out in the south of Malakal after soldiers commanded by Major General Johnson Olony, who had previously led the principally Shilluk South Sudan Defence Movement/Army, complained about unpaid wages. Members of the Abialang Dinka, who live close to Paloich, report that the SPLA is training 1,500 new recruits due to desertions and troops joining the rebels. -

Jonglei Unity Upper Nile

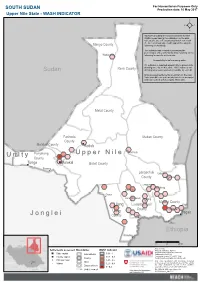

For Humanitarian Purposes Only SOUTH SUDAN Production date: 10 May 2017 Upper Nile State - WASH INDICATOR REACH calculated the areas more likely to have WASH needs basing the estimation on the data collected between February and March 2017 with the Area of Knowledge (AoK) approach, using the Manyo County following methodology. The indicator was created by averaging the percentages of key informants (KIs) reporting on the Wadakona following for specific settlements: - Accessibility to safe drinking water 0% indicates a reported impossibility to access safe Renk County drinking water by all KIs, while 100% indicates safe Sudan drinking water was reported accessible by each KI. Only assessed settlements are shown on the map. Values for different settlements have been averaged and represented with hexagons 10km wide. Melut County Fashoda Maban County County Malakal County Kodok Panyikang Guel Guk Ogod U p p e r N i l e U n i t y County Tonga Malakal Baliet County Pakang Longochuk Udier County Chotbora Longuchok Mathiang Kiech Kon Dome Gum (Kierwan) Mading Maiwut County Ulang Luakpiny/Nasir Kigili County Maiwut Ulang Pagak J o n g l e i County Jikmir Jikou Ethiopia Wanding Sudan 0 25 50 km Data sources: Ethiopia Settlements assessed Boundaries WASH indicator Thematic indicators: REACH Administrative boundaries: UNOCHA; State capital International 0.81 - 1 Settlements: UNOCHA; County capital 0.61 - 0.8 Coordinate System:GCS WGS 1984 C.A.R. County Contact: [email protected] Principal town 0.41 - 0.6 Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Juba State Village 0.21 - 0.4 on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, Disputed area associates, donors or any other stakeholder D.R.C. -

Upper Nile State Map (As of Dec 2016)

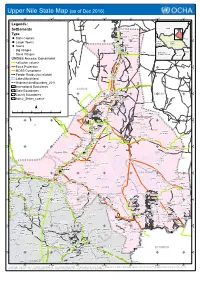

Upper Nile State Map (as of Dec 2016) 31°E 31°30'E 32°E 32°30'E 33°E 33°30'E 34°E Legends: Sudan ! B! ulli Island Settlements Mashra Hamadok Type ! Er Rayat ! Meheida Esh S ! !Girbanat State Capitals Tayyibah! ! Ethiopia N Sahlat N ° Gerger ! ° 2 " ! 2 1 " Wad Battah Central 1 ! South Larger Towns Fur African Mangara ! Sudan ! ! Ez Zeraf ! ! ! Republic " ! E!l Alali Wunbut Towns ! ! El Mashash Arbeit Fanna Maboich! ! ! Manyo Big Villages Nyetong Qawz Rom ! ! Abu Gaw Kenya ! ! Democratic ! R! enk " ! ! Republic of Congo Small Villages Abbeit Uganda ! Agum Gaikwach UNDSS Access Constraint ! Makha! da Warrit <all other values> ! N N ' ' 0 ! Frisan 0 3 3 ° Force Protection ° 1 1 1 1 Tareifing Alek ! MOSS Compliance ! ! Giel Luentam! Feeder Roads (not reliable) ! Renk ! Molbok! ! Anok Lakes/Marshland Nabaqaya UndeterminedBoundary_2011 ! Turaybah International Boundaries SUDAN ! Ugeiz State Boundaries ! !El-Galhak ! N Torakit ! N ° ! ! ° ! Awong 1 ! Aga!lak Wad An Nasir! 1 1 Umm Bra!bit ! ! 1 ! SUDAN County Boundaries ! Bibban ! ! Manang ! Tau ! ! Ad!al Mimnu!n Gezirat Ed Dibeiker Nyangenlwal Adm2_States_coarse El Guroh ! ! ! Atai ! ! ! Gogotok Tibnah Qawz Abu Ramad ! Rom ! ! ! Adeiri ! ! ! Kopyot ! ! Beimachok ! Arei Aiyota Akorwet ¯ Kwa El Mango ! ! ! Aturuk 0 10 20 40 60 80 100 ! Wunayan El Fuj Kilometers ! ! El Haragis ! ! Kaka W!unyat Domaia Ez Zei ! Dolbek ! ! Domat " ! ! ! Gabek Hawaga Z!arzor ! ! Dok ! ! ! ! Ku!dda Fariak ! ! Akurwa Tir ! ! N ! N ' Zurzur Korpar ' 0 Akot 0 3 ! Ban Bu!rka 3 ° ° Fojbe 0 ! Paloich 0 1 Melut ! ! 1 " Dar -

South Sudan - Upper Nile State South Sudan Displacement Crisis Assessment of Hard-To-Reach Areas in South Sudan May 2017

South Sudan - Upper Nile State South Sudan Displacement Crisis Assessment of Hard-to-Reach Areas in South Sudan May 2017 Overview Assessment coverage In 2014 and 2015, Upper Nile State was the site of some data in hard-to-reach areas of Unity State. Juba PoC1 and PoC3, as well as recently arrived IDPs of the most intense conflict in South Sudan. Although In December 2016, REACH decided to refine the in Akobo. Data collection was expanded to Renk in Upper 158 Key Informants assessed the state had enjoyed a period of relative calm in 2016, methodology, moving from the AoO to the Area of Nile State in April 2017. since January 2017, conflict has reignited across the Knowledge (AoK) methodology, an approach collecting Data collected is aggregated to the settlement level and all 99 Settlements assessed state. Many areas in Upper Nile are largely inaccessible information at the settlement level. The most recent percentiles presented in this factsheet, unless otherwise Contact with Area of Knowledge to humanitarian actors due to insecurity and logistical OCHA Common Operational Dataset (COD) released specified, represent percent of settlements within Upper constraints. As a result, only limited information is in February 2016 has been used as the reference for Nile with that specific response. The displacement section KIs reported to be newly arrived available on the humanitarian situation outside major settlement names and locations. Through AoK, REACH on page 2 refers to the proportion of assessed KIs arrived 98% IDPs. displacement sites. collects data from a network of Key Informants (KIs) who within the previous month (newly arrived IDPs). -

GOAL EMR062.16 Report

Final Report Presented to the Isle of Man Government Provision of essential supplies to support lifesaving humanitarian assistance for conflict affected and displaced populations in Upper Nile State, South Sudan A supply delivery in Ulang County Introduction Humanitarian needs in South Sudan are at their highest since the December 2013 conflict that led three million to flee their homes as IDPs or refugees to neighbouring countries. The conflict in South Sudan is showing little sign of abating. In 2016, the humanitarian crisis in South Sudan deepened and spread, affecting people in areas previously considered stable and exhausting the coping capacity of those already impacted. The Humanitarian Needs Overview estimated that nearly 7.5 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance and protection across the country as per the end of 2016, as a result of armed conflict, inter-communal violence, economic crisis, disease outbreaks and climatic shocks. The government of the Isle of Man supported GOAL with a £20,000 grant to provide vital and life-saving health and nutrition programming to vulnerable and conflict-affected populations of Melut, Maiwut and Ulang Counties, Upper Nile State. Project Aim This project aimed at providing lifesaving humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected and displaced populations in Upper Nile State, South Sudan. Project Objectives This project intended to deliver supplies to GOAL field sites in Upper Nile State. Programmatic and operational supplies stored in GOAL warehouse in Juba needed to be urgently airlifted to Melut, Maiwut and Ulang Counties in order to avoid any supply chain Melut rupture, especially for drugs and food commodities needed for primary health care facilities and nutrition services. -

Displaced and Immiserated: the Shilluk of Upper Nile in South

Report September 2019 DISPLACED AND IMMISERATED The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19 Joshua Craze HSBA DISPLACED AND IMMISERATED The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19 Joshua Craze HSBA A publication of the Small Arms Survey’s Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan project with support from the US Department of State Credits Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, 2019 First published in September 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Coordinator, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Rebecca Bradshaw Fact-checker: Natacha Cornaz ([email protected]) Copy-editor: Hannah Austin ([email protected]) Proofreader: Stephanie Huitson ([email protected]) Cartography: Jillian Luff, MAPgrafix (www.mapgrafix.com) Design: Rick Jones ([email protected]) Layout: Frank Benno Junghanns ([email protected]) Cover photo: A man walks through the village of Aburoc, South Sudan, as an Ilyushin Il-76 flies over the village during a food drop as part of a joint WFP–UNICEF Rapid Response Mission on 13 May 2017. -

County Social Map Malakal COUNTY SOUTH SUDAN

COUNTY SOCIAL MAP MALAKAL COUNTY SOUTH SUDAN OVERVIEW Malakal County hosts the capital of the former Upper Nile State. Malakal town is the headquarters of Malakal County, which is located on the banks of the White Nile, just north of its confluence with the Sobat River. Since 2013 Malakal has been the site of numerous battles, and has been overrun on various occasions. As of October 2015, Malakal had changed hands 12 times, and was destroyed NORTHERN many times in the process. MALAKAL Challenges in Malakal, particularly those related to e Nile immunization, have multiple dimensions. Inaccessibility, lack of Whit security, poor infrastructure and seasonality are a few of them. OGOD It also hosts a substantial number of the mobile population, OBAU including internally displaced people. CENTRAL MALAKAL KEY CHALLENGES SOUTHERN MALAKAL • Due to repeated changing of hands, it is less feasible to invest in long-term infrastructure development. • Year round, air is the only feasible mode of transportation. Risk • Most areas become inaccessible during the rainy season. • A substantial portion of the population is on the move. Low • Very high implementation cost. Medium • Limited access due to political uncertainty. High RISK AND ACCESS ANALYSIS Malakal County can be divided into three zones, based on the extent of risk. The north, north-west and most parts of the west, comprising Makal, Ogod and Malakal payams, are in a FAST FACTS low-risk zone. Obau Payam, in the south and south-west, are in • Payams: 6 a medium-risk zone and Bokany and Aywangen are in a high- risk zone. • Villages: 20 Besides the lack of security, rain is a key factor associated with access.