Here to Be Objectively Apprehended

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film After Authority: the Transition to Democracy and the End of Politics Kalling Heck University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2017 Film After Authority: the Transition to Democracy and the End of Politics Kalling Heck University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Heck, Kalling, "Film After Authority: the Transition to Democracy and the End of Politics" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1484. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1484 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FILM AFTER AUTHORITY THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY AND THE END OF POLITICS by Kalling Heck A Dissertation SubmitteD in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2017 ABSTRACT FILM AFTER AUTHORITY THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY AND THE END OF POLITICS by Kalling Heck The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Patrice Petro A comparison of films maDe after the transition from authoritarianism or totalitarianism to Democracy, this Dissertation aDDresses the ways that cinema can Digest anD extenD moments of political transition. By comparing films from four Different nations—the Italian Germany Year Zero, Hungarian Sátántangó, South Korean Woman on the Beach, anD American Medium Cool—in relation to iDeas Drawn from critical anD political theory, this project examines how anD why these wilDly Diverse films turn to ambiguity as their primary means to Disrupt the ravages of unchecked authority. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Chris Cutler, Loops Analogiques, Digitales, À L'unisson, Déphasées, Multipistes, Échantillonnées Ou Improvisées. Les Usage

Culture, le magazine culturel en ligne de l'Université de Liège Chris Cutler, Loops Analogiques, digitales, à l'unisson, déphasées, multipistes, échantillonnées ou improvisées. Les usages que revêtent les boucles musicales sont multiples. Elles se déploient dans les studios d'enregistrement, envahissent les radios, tournent dans les supermarchés, ou accompagnent les jeux vidéo. On les a d'abord entendues chez Pierre Schaeffer et Karlheinz Stockhausen, ou peut-être avant dans les premiers synthétiseurs, voire en appelant les premières horloges parlantes. On les entendait surtout lorsque les disques se rayaient depuis le début du 19 e siècle. Elles ont conquis Steve Reich et Terry Riley, puis Brian Eno et Kraftwerk, Grandmaster Flash et Boards of Canada. Il était même des humains pour les imiter : Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham avec leurs armées de guitares en premier. Boucles et répétitions semblent avoir bel et bien assujetti le monde à l'aube du 21 e siècle. C'est afin d'interroger les multiples usages et sens de la boucle et de distinguer cette structure des autres formes de répétition dans son rapport au temps et à l'espace qu'est né le projet « Understanding the Loop » sous les auspices du CIPA (Centre Interdisciplinaire de Poétique Appliquée). Ce projet prend également en considération de façon historique les techniques et spécificités historiques propres aux différentes formes d'art où on lui reconnaît un rôle prépondérant ; tout comme de rendre compte des manières distinctes de moduler la répétition qui dépassent le simple argument trop souvent avancé de la logique « non linéaire » qui serait mise en place par la boucle. -

What Is Most Likely the End of the Late Harold

What is most likely the end of the late Harold Camping’s Biblical Calendar according to all he showed that was trustworthy, and what he would have known today based on the his proven ability to be corrected throughout a fifty year ministry? INTRODUCTION: ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ According to the information in his books, and a more faithful understanding of the scriptures, follows a simplified calendar, Table 1, the late Harold Camping could have likely arrived at, had he not repeatedly been pressured to publish his works prematurely. It can be seen today how Mr. Camping’s study on the gospel time line had been sabotaged. The year 2024 A.D. could be the conclusion to Mr. Camping’s study his May 21, 2011 calendar had ultimately been pointing to. By, 2012, my eyes had been fully opened to the two virgin birth dates in Harold’s calendar, [7 B.C. & 1 A.D.]. In, 2015, after reading afresh Harold’s 1994? Book; an exceedingly interesting quote was then found on, page, 440, that clearly exposed the same excess of 7 years that exists between, 1 A.D., and, 7 B.C. His statement from his book 1994? follows: “That is, creation occurred 11,000 years, (remember 11,000 + 6 years), before Christ, (Camping, H. 1994?).” Table 1 Adam’s sin The Exodus King Christ’s The Israel Sep May Yet other Yet other against the Noachian From David’s Virgin Lord’s The Fig 6, 21 Seven Seven Law of God Flood Egypt Israel Birth Atonement Tree 1994 2011 Years Years Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Earth Year Zero 6023 9566 10006 11006 11045 12960 13000 13017 13023 13030 11006 B.C. -

Diplomová Práce 2016

Diplomová práce 2016 Petra Veselá Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Diplomová práce Procesy Plastic People of the Universe v kontextu totalitního režimu Petra Veselá Plzeň 2016 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra historických věd Studijní program Historické vědy Studijní obor Moderní dějiny Diplomová práce Procesy s Plastic People of the Universe v kontextu totalitního režimu Petra Veselá Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Lukáš Novotný, Ph.D. Katedra historických věd Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2016 ……………………… Touto cestou bych ráda poděkovala PhDr. Lukáši Novotnému, Ph.D. za odborné vedení mé diplomové práce. 1. Obsah 1. Úvod ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Vývoj k procesům s undergroundem .................................................................................... 6 2.1 Společnost v období „normalizace“ 1969–1975 ........................................................... 6 2.2 Formování undergroundu jakožto nezávislého kulturního prostředí ............................ 8 2.3 Jednotlivé etapy undergroundu ................................................................................... 10 2.4 Vznik kapely Plastic People of the Universe a první narušení normalizace ............... 11 2.5 Postoj totalitního režimu k undergroundu .................................................................. -

PROBES #23.2 Devoted to Exploring the Complex Map of Sound Art from Different Points of View Organised in Curatorial Series

Curatorial > PROBES With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes PROBES #23.2 devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points of view organised in curatorial series. Auxiliaries PROBES takes Marshall McLuhan’s conceptual The PROBES Auxiliaries collect materials related to each episode that try to give contrapositions as a starting point to analyse and expose the a broader – and more immediate – impression of the field. They are a scan, not a search for a new sonic language made urgent after the deep listening vehicle; an indication of what further investigation might uncover collapse of tonality in the twentieth century. The series looks and, for that reason, most are edited snapshots of longer pieces. We have tried to at the many probes and experiments that were launched in light the corners as well as the central arena, and to not privilege so-called the last century in search of new musical resources, and a serious over so-called popular genres. This auxilliary digs deeper into the many new aesthetic; for ways to make music adequate to a world faces of the toy piano and introduces the fiendish dactylion. transformed by disorientating technologies. Curated by Chris Cutler 01. Playlist 00:00 Gregorio Paniagua, ‘Anakrousis’, 1978 PDF Contents: 01. Playlist 00:04 Margaret Leng Tan, ‘Ladies First Interview’ (excerpt), date unknown 02. Notes Pianist Margaret Leng Tan was born in Singapore, where as a gifted student she 03. Links won a scholarship to study at the Julliard School in New York. In 1981 she met 04. Credits and acknowledgments John Cage and worked with him then until his death in 1992. -

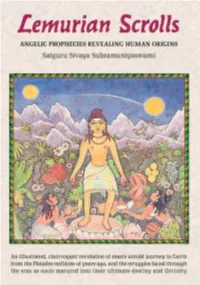

Lemurian-Scrolls.Pdf

W REVIEWS & COMMENTS W Sri Sri Swami Satchidananda, people on the planet. The time is now! Thank you Founder of Satchidananda so much for the wonderful information in your Ashram and Light of Truth book! It has also opened up many new doorways Universal Shrine (LOTUS); for me. renowned yoga master and visionary; Yogaville, Virginia K.L. Seshagiri Rao, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus, Lemurian Scrolls is a fascinating work. I am sure University of Virginia; Editor of the quarterly the readers will find many new ideas concern- journal World Faiths ing ancient mysteries revealed in this text, along Encounter; Chief Editor with a deeper understanding of their impor- of the forthcoming tance for the coming millenium. Encyclopedia of Hinduism Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, a widely recog- Patricia-Rochelle Diegel, nized spiritual preceptor of our times, un- Ph.D, well known teacher, veils in his Lemurian Scrolls esoteric wisdom intuitive healer and concerning the divine origin and goal of life consultant on past lives, for the benefit of spiritual aspirants around the human aura and numerology; Las Vegas, the globe. Having transformed the lives of Nevada many of his disciples, it can now serve as a source of moral and spiritual guidance for I have just read the Lemurian Scrolls and I am the improvement and fulfillment of the indi- amazed and pleased and totally in tune with vidual and community life on a wider scale. the material. I’ve spent thirty plus years doing past life consultation (approximately 50,000 to Ram Swarup, intellectual date). Plus I’ve taught classes, seminars and re- architect of Hindu treats. -

Freier Download BA 58 Als

BAD 58 ALCHEMY 1 STEINER: ... Die Musik besiegt den Tod, aber dann besiegt das Mysterium tremendum die Musik. Orpheus stirbt, von den Mänaden zerrissen. Dann kommt etwas, das für uns heute abend wichtig ist: Der Körper blutet aus, aber, das ist eine archaische Überlieferung, der Kopf singt weiter. Aus dem Mund des toten Orpheus strömt Musik. Das zweite Thema ist Marsyas, dieser grausame, furchtbare Mythos vom Kampf zwischen ihm und Apollon, in dem Marsyas geschändet wird. Auf Tizians berühmtem Gemälde finden wir alle Motive unseres heutigen Gesprächs. Es ist das größte seiner Bilder, und auch das grausamste. Worum ging es in dem Kampf? In dem Logos Apollons heißt es: Musik ist das Ornament der Sprache. Und Marsyas sagt: Der Wind ist Musik, der Vogel singt Musik, das Meeresrauschen ist Musik. Die Sprache ist ein später Gast und ein falscher. Dann das Sirenen-Motiv. Der Gesang tötet, er hält ganz mysteriös das Versprechen. Was sagen die Sirenen? Wir können dir sagen, was in der Welt war, was in der Welt ist und was in ihr sein wird. Die Verheißung des Alten Testa- ments. Die Verheißung des Baums im Paradies, des Baums der Wissenschaft, des Wissens. Hör unserem Gesang zu. Odysseus überlebt, er segelt weiter. Das war der letzte Moment, wo der Mensch in der Musik die Urkraft der Schöpfung hören konnte. Aber die Warnung war da: Musik ist übermenschlich, aber auch unmenschlich. Schopenhauer sagt: Auch wenn die Welt nicht wäre, könnte die Musik bestehen. Ich bin sicher, der Satz stimmt. Zuerst sind wir Gäste der Musik. Vielleicht kommt die Sprache erst viel später. -

Table of Contents

Table of contents 1. Prologue 3 Introduction 3 “RIO” – categorical misuse 4 A “true” progressive 4 Arnold Schonberg 7 Allan Moore 11 Bill Martin 15 2. California Outside Music Assiciation 19 The story begins 19 Coma coming out 22 Demographical setting, booking and other challenges 23 An expanding festival 23 A Beginner’s Guide 26 Outside music – avant rock 27 1980’s “Ameriprog”: creativity at the margins 29 3. The Music 33 4. Thinking Plague 37 ”Dead Silence” 37 Form and melody 37 The song ”proper” 40 Development section 42 Harmonic procedures and patterns 45 Non-functional chords and progressions 48 Polytonality: Vertical structures and linear harmony 48 Focal melodic lines and patterns 50 Musical temporality – ”the time of music” 53 Production 55 5. Motor Totemist Guild / U Totem 58 ”Ginger Tea” 62 Motives and themes 63 Harmonic patterns and procedures 67 Orchestration/instrumentation 68 Production 69 ”One Nail Draws another” and ”Ginger Tea” 70 1 6. Dave Kerman / The 5UU’s 80 Bought the farm in France… 82 Well…Not Chickenshit (to be sure…) 84 Motives and themes / harmony 85 Form 93 A precarious song foundationalism 95 Production, or: Aural alchemy - timbre as organism 99 7. Epilogue 102 Progressive rock – a definition 102 Visionary experimentalism 103 Progressive sensibility – radical affirmation and negation 104 The ”YesPistols” dialectic 105 Henry Cow: the radical predecessor 106 An astringent aesthetic 108 Rock instrumentation, -background and –history 109 Instrumental roles: shifts and expansions 109 Rock band as (chamber) orchestra – redefining instr. roles 110 Timbral exploration 111 Virtuosity: instrumental and compositional skills 114 An eclectic virtuosity 116 Technique and “anti-technique” 117 “The group’s the thing” vs. -

NEWS 2017 Working on Piano Concerto to Be Played at Ars Musica 2020 by Daan Vandewalle.. March 23, Bass Clarine

TIM HODGKINSON: NEWS 2017 Working on Piano Concerto to be played at Ars Musica 2020 by Daan Vandewalle.. March 23, bass clarinet with Hyperion Ensemble in Bucharest. April, teach course at Cagliari Conservatoire on Shamanism and Technology. April-May, run improvisation workshops at Split with S/UMAS contemporary music ensemble; performance at Izlog Suvremenog Zvuka Festival Zagreb. May 6, play Tectonics Festival Glasgow in trio with Shelley Hirsch and Paul May, broadcast on BBC Radio 3. May-June, write Palace of Projects, commissioned by Hoca Nasreddin, Istanbul, for voice, tenor saxophone, and kaval. June, composition workshop at ON-Büro, Köln, and solo concert at Stadtgarten. Aug 17, Konk Pack play Le Bruit de la Musique Festival, France. September, Hyperion Ensemble at Enescu Festival, Bucharest, and Kanjizsa Festival, Serbia, on September 16: first performance of new piece Chorismos. Polish Radio concert at Warsaw, Sep 26, second performance of Chorismos. Sacrum et Profanum Festival, Krakow, Sep 30, conducted by Iancu Dumitrescu and Ilan Volkov. 2018 January: gigs and workshops in Naples and Rome with Fabrizio Spera and Gandolpho Pagano. Trio adopts name TORBA. Duo with Yoni Silver at Hundred Years' Gallery. March: tour of Denmark with Martin Klapper and Peter Ole Jorgensen. June: Lindsay Cooper Songbook group at Cafe Oto + Zappanale Fest, Bad Doberan, Germany July 2, duo with Shusui Enomoto at Shakuhachi Festival, Goldsmiths Aug: Guest with Oxbow group on electric alto saxophone @ Oslo Hackney, London Sep: Konk Pack tour: Toronto Guelph Festival, San Diego, Austin, Houston, New Orleans, duo gig with Chris Cochrane in NYC. Oct: with Martin Klapper and Peter Ole Jorgensen, gigs in Copenhagen, Pardubice, Prague, Ostrava Nov: tour Japan with Chris Cutler and Yumi Hara as The Watts. -

Magorův Zápisník Ivan Martin Jirous Znění Tohoto Textu Vychází Z Díla Magorův Zápisník Tak, Jak Bylo Vydáno Nakladatelstvím Torst V Praze V Roce 1997

Magorův zápisník Ivan Martin Jirous Znění tohoto textu vychází z díla Magorův zápisník tak, jak bylo vydáno nakladatelstvím Torst v Praze v roce 1997. Pro potřeby vydání Městské knihovny v Praze byl text redakčně zpracován. § Text díla (Ivan Martin Jirous: Magorův zápisník), publikovaného Městskou knihovnou v Praze, je vázán autorskými právy a jeho použití je definováno Autorským zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb. Vydání (obálka, upoutávka, citační stránka a grafická úprava), jehož autorem je Městská knihovna v Praze, podléhá licenci Creative Commons Uveďte autora-Nevyužívejte dílo komerčně-Zachovejte licenci 3.0 Česko. Verze 1.0 z 28. 2. 2020. OBSAH I . 8 Eva Fuková . 9 JaromírZ Funke . 11 Konstruktivní tendence. .13 ateliéru Dušana Kadlece. .16 Zemřel Lucio Fontana. .18 Otevřené možnosti. 24 Marcel Duchamp. 32 Pavel Laška. .34 Socha v plenéru. .36 Socha piešťanských parků 69. 44 Američané v Praze. 4955 ComicsI . 5552 3× Naděžda Plíšková. III. Grafika Naděždy Plíškové. .57 . 58 Beatles v obrazech. 60 Sochy pro budoucí město?. .62 Otakar Slavík Karel Nepraš. 68 Čas unáší Krásu Čas odhaluje Pravdu. 71 Několik pražských výstav . .75 Sporckův Kuks aneb Od minulosti k utopii. .81 Kamil Linhart . 90 Jan a Josef Wagnerovi. .92 Liběchov Václava Levého. 94 Konfrontace II . 97 Pocta Andy Warholovi. .99 Tato výstava . .109 Divnost, že vůbec jsme. .112 Zpráva o činnosti Křižovnické školy . 116 Eugen Brikcius. .125 Bude religiózní, nebo…. .129 II Fotografie Jana Šafránka . .133 Ach Nachtigal. 134 . .139 Mesaliance, či zásnuby mezi beatovou hudbou a výtvarným uměním? . .140 II. beatový festival. 145 SedmáI generace romantiků . 149 ZprávaII o třetím českém hudebním obrození. 158 III. 158 IV. -

Chris Cutler/Fb Frith

6 6 EM&RION OF HENRY M U " C a m b r id g e U n i v e r s i t y - CHRIS CUTLER/FB FRITH 7 1 HENRY COId* ^°ndon oN 8L ASIDII BlIRY FAYRE ^ TOURED WITH F A U S TAMt> APPGACE0 W Y M H R 5 : 7o DANCE HAIL" 74 2LP #---- T 5?---------- HENRY COW lEGEN^TBLFl” “ " 7i SLAPPHAPPYS 73 FAUST ’v*"-*****- X X X WERNER 60NTFR HANS- RUDOLF GEOFF TIM f r b d J o h n DA&MAR PETER ANTHONY JE A N ' CHRIS ' z a p p a ' viusthoffJOachiM so s Na LEIGH HOP&KIHSON f r it h g r e a v e s KRAUSE &LEG/AD MOCRE HER YB CUTLER PERO.N DIERMEIER RA|LER WIND KEY&/WIWD PROMS VIOUN/GUITAR &ASS l________ -I-------------------- 1 P.BIE6VAD TOURED AS FAUST'S MEMBER IN THEIR '73 &RITUH TOUR . 'A SORT Op' 72. — CRAZY * 27574 HENRY COW 'UNRESr'74 IP x 'SLAPP HAPPY'T* — MABEL731"-™ CHRIS FRED • JOHN 'CASABIANCA MOON'— i HODGKIN SON COO CUTLER. PRCTH <bREAVPS SESSION l--------------- ____L ___ I____ __ I___ wows i t 0 14 PESfERATC STRA1GHTS' 7S LP i O 7b HENRY CM/MPHAPP'’IN PRAISE C F lEARWlUG' 7 5 Lf 1-----------------1-------------- ------------1--------------------- 1---------------- 1 TIM LINDSAY CwftS FRED J OWN DAMMAR PETER ANTHONY MODGKIUSON cooper CUTLER. PRITH GREAVES KRAUSE Moo Re ___I___ ___ I_____ ----------1 1 -H So lo FEATURED* ROBERT 4 S H 0 1 R Y C O U * 'CONCERTS'2Lf 76 WYATT GR6 W AND DREW BETWEEN o n ow e T 'IU UNDSAY FRED CHRIG DAG MAR JOHN MARCH S 0 a n d m a y e>9 B Y HOD6WNSON CoopgR.