Prologue with Two Tubs—One for Rinsing and the Other for Soaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WINGS of HONNEAMISE Oe Ohne) 7 Iy

SBP ee TON ag tatUeasai unproduced sequel to THE WINGS OF HONNEAMISE oe Ohne) 7 iy Sadamoto Yoshiyuki © URU BLUE The faces and names you'll need to know forthis installment of the ANIMERICA Interview with Otaking Toshio Okada. INTERVIEW WITH TOSHIO OKADA, PART FOUR of FOUR In Part Four, the conclusion of the interview, Toshio Okada discusses the dubious ad cam- paign for THE WINGS OF HONNEAMISE, why he wanted Ryuichi Sakamotoforits soundtrack, his conceptfor a sequel and the “shocking truth” behind Hiroyuki Yamaga’‘s! Ryuichi Sakamoto Jo Hisaishi Nausicaa Celebrated composer whoshared the Miyazaki’s musical composer on The heroine of whatis arguably ANIMERICA: There’s something I’ve won- Academy Award with David Byrne mostofhis films, including MY Miyazaki’s most belovedfilm, for the score to THE LAST EMPEROR, NEIGHBOR TOTORO; LAPUTA; NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF dered aboutfor a long time. You know,the Sakamotois well known in both the NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF WIND,Nausicaais the warrior U.S. andJapan for his music, both in WIND; PORCO ROSSOand KIKI’S princess of a people wholive ina ads forthe film had nothing to do with the Yellow Magic Orchestra and solo. DELIVERY SERVICE. Rvorld which has been devadatent a 1 re Ueno, Yuji Nomi an a by ecological disaster. Nausicaa actual film! we composedcai eae pe eventually managesto build a better 7 S under Sakamatne dIcelon, life for her people among the ruins . : la etek prcrely com- throughhernobility, bravery and Okada: [LAUGHS] Toho/Towa wasthe dis- pasetiesOyromaltteats U self-sacrifice.. tributor: of THE WINGS OF HONNEAMISE, “Royal SpaceForce Anthem,” and and they didn’t have any know-how,or theSpace,”“PrototypeplayedC’—ofduringwhichthe march-of-“Out, to sense of strategy to deal with< the film.F They Wonthist ysHedi|thefrouaheiation.ak The latest from Gainaxz handle comedy, and comedy anime—what. -

Release of Episodes 7 to 12 of VLADLOVE, Mamoru Oshii and Junji

Make The World More Sustainable March 3, 2021 Ichigo Ichigo Animation Release of Episodes 7 to 12 of VLADLOVE, Mamoru Oshii and Junji Nishimura’s New Anime Series on March 14, 2021! Introducing Images from the Second Half of the Series! Renowned anime director Mamoru Oshii is known for breakthrough works such as PATLABOR: The Movie and Ghost in the Shell. VLADLOVE, written and directed by Oshii, is his first collaboration with Junji Nishimura since Urusei Yatsura, and Episodes 1 to 6 were released on February 14, 2021. Oshii’s strong desire to make a powerful, lasting impact is evident in the series. In the second half of VLADLOVE, Oshii stays true to his words “I will show you what happens when an old fogey gets cranky,” and pushes his art to another level. Enjoy VLADLOVE, a work which is rocking the foundations of modern Japanese anime. * Please see below the streaming platforms where you can watch VLADLOVE. 1 A Complete VLADLOVE Guide (in Japanese) Will Go on Sale on March 5, 2021! Currently Accepting Advanced Orders! How did a comedy about a high school girl and a beautiful vampire come to life? In VLADLOVE, Oshii weaves in many references to his works over the past decades. What was the intention behind that scene? What was the inspiration for that character? The guide answers these questions and more, offering a behind-the-scenes look into the production process. Illustration Gallery, Main Character Introductions and Images, Explanations of All Episodes, Cast Interviews, Storyboards of All Episodes, Images Selected by the Key Animation -

An Examination of Otaku Masculinity in Japan

!"#$%&'($)*&+',-(&.#(&/'(&0'"&(/#&(/"##1+23#,42',$%5!& $,$32,$(2',&'0&'($)*&3$47*%2,2(8&2,&9$:$,& & & $&(/#424& :;<=<>?<@&?A& (B<&0CDEF?G&AH&?B<&+<IC;?J<>?&AH&$=KC>&4?E@K<=& 7AFA;C@A&7AFF<L<& & & & 2>&:C;?KCF&0EFHKFFJ<>?&AH&?B<&"<MEK;<J<>?=&HA;&?B<&+<L;<<& NCDB<FA;&AH&$;?=& & NG&& N<>OCJK>&)K<PFCP& 3CG&QRST& & & & '>&JG&BA>A;5&25&N<>OCJK>&)K<PFCP5&BCU<&>A?&;<D<KU<@&C>G&E>CE?BA;KV<@& C==K=?C>D<&A>&?BK=&?B<=K=W&2&BCU<&HEFFG&EIB<F@&?B<&/','"&7'+#&AH&7AFA;C@A& 7AFF<L<W&& & & & & & & & XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX& & N#,9$32,&)2#)%$)& & & & & & & & Q& & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & ^& & ($N%#&'0&7',(#,(4& & & /A>A;&7A@<WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWQ& & "<C@<;`=&$II;AUCFWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWY& & (C\F<&AH&7A>?<>?=&WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW_& & (C\F<=WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWa& & 2>?;A@ED?KA>WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWb& & 7BCI?<;&S]&/K=?A;KDCF&7A>?<c?WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWSQ& & 7BCI?<;&Q]&'?CPE&K>&?B<&:;<=<>?&+CGWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWQQ& & 7BCI?<;&Y]&3C=DEFK>K?G&K>&9CIC>]&'?CPE&C>@&4CFC;GJ<>WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWYS& & 7A>DFE=KA>WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW^R& -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Viewed and Discussed in Wired Magazine (Horn), Japan's National Newspaper the Daily Yomiuri (Takasuka),And the Mainichi Shinbun (Watanabe)

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 You Are Not Alone: Self-Identity and Modernity in Neon Genesis Evangelion and Kokoro Claude Smith III Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ASIAN STUDIES YOU ARE NOT ALONE: SELF-IDENTITY AND MODERNITY IN NEON GENESIS EVANGELION AND KOKORO By CLAUDE SMITH III A Thesis submitted to the Department of Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Claude Smith defended on October 24, 2008 . __________________________ Yoshihiro Yasuhara Professor Directing Thesis __________________________ Feng Lan Committee Member __________________________ Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii My paper is dedicated in spirit to David Lynch, Anno Hideaki, Kojima Hideo, Clark Ashton Smith, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, and Murakami Haruki, for showing me the way. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like very much to thank Dr. Andrew Chittick and Dr. Mark Fishman for their unconditional understanding and continued support. I would like to thank Dr. Feng Lan, Dr. Erndl, and Dr. Yasuhara. Last but not least, I would also like to thank my parents, Mark Vicelli, Jack Ringca, and Sean Lawler for their advice and encouragement. iv INTRODUCTION This thesis has been a long time in coming, and was first conceived close to a year and a half before the current date. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented In

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By George Andrew Stey Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance, Advisor Professor Maureen Hildegarde Donovan Professor Philip C. Brown Copyright by George Andrew Stey 2009 Abstract Certain works of Japanese animation appear to strive to approach reality, showing elements of realism in the visuals as well as the narrative, yet theories of film realism have not often been applied to animation. The goal of this thesis is to systematically isolate the various elements of realism in Japanese animation. This is pursued by focusing on the effect that film produces on the viewer and employing Roland Barthes‟ theory of the reality effect, which gives the viewer the sense of mimicking the surface appearance of the world, and Michel Foucault‟s theory of the truth effect, which is produced when filmic representations agree with the viewer‟s conception of the real world. Three directors‟ works are analyzed using this methodology: Kon Satoshi, Oshii Mamoru, and Miyazaki Hayao. It is argued based on the analysis of these directors‟ works in this study that reality effects arise in the visuals of films, and truth effects emerge from the narratives. Furthermore, the results show detailed settings to be a reality effect common to all the directors, and the portrayal of real-world problems and issues to be a truth effect shared among all. As such, the results suggest that these are common elements of realism found in the art of Japanese animation. -

Nihilism and Existentialist Rhetoric in Neon Genesis Evangelion

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Tsukuba Repository 〈Articles〉Beyond 2015 : Nihilism and Existentialist Rhetoric in Neon Genesis Evangelion 著者 TSANG Gabriel F.Y. journal or Journal of International and advanced Japanese publication title studies number 8 page range 35-43 year 2016-03 URL http://doi.org/10.15068/00146740 © 2016 Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies Vol. 8, February 2016, pp. 35–43 Master’s and Doctoral Program in International and Advanced Japanese Studies Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba Article Beyond 2015: Nihilism and Existentialist Rhetoric in Neon Genesis Evangelion Gabriel F. Y. TSANG King’s College London, Department of Comparative Literature, Ph.D. Student Generally categorized as low art, Japanese manga and anime draw insufficient overseas critical attention, regardless of their enormous cultural influence in East Asia. Their popularity not simply proved the success of cultural industrialization in Japan, but also marks a series of local phenomena, reflecting social dynamicity and complexity, that deserve interdisciplinary analysis. During the lost decade in the 1990s, which many scholars studied with economic accent (Katz 1998, Grimes 2001, Lincoln 2001, Amyx 2004, Beason and Patterson 2004, Rosenbluth and Thies 2010), manga and anime industry in Japan entered its golden age. The publication and broadcast of some remarkable works, such as Dragon Ball, Sailor Moon, Crayon Shin-chan and Slam Dunk, not only helped generate huge income (nearly 600 billion yen earned in the manga market in 1995) that alleviated economic depression, but also distracted popular focus from the urge of demythologising national growth. -

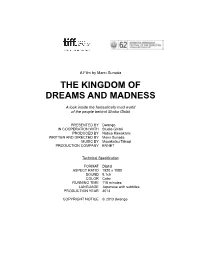

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness

A Film by Mami Sunada THE KINGDOM OF DREAMS AND MADNESS A look inside the fantastically mad world of the people behind Studio Ghibli PRESENTED BY Dwango IN COOPERATION WITH Studio Ghibli PRODUCED BY Nobuo Kawakami WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Mami Sunada MUSIC BY Masakatsu Takagi PRODUCTION COMPANY ENNET Technical Specification FORMAT Digital ASPECT RATIO 1920 x 1080 SOUND 5.1ch COLOR Color RUNNING TIME 118 minutes LANGUAGE Japanese with subtitles PRODUCTION YEAR 2013 COPYRIGHT NOTICE © 2013 dwango ABOUT THE FILM There have been numerous documentaries about Studio Ghibli made for television and for DVD features, but no one had ever conceived of making a theatrical documentary feature about the famed animation studio. That is precisely what filmmaker Mami Sunada set out to do in her first film since her acclaimed directorial debut, Death of a Japanese Salesman. With near-unfettered access inside the studio, Sunada follows the key personnel at Ghibli – director Hayao Miyazaki, producer Toshio Suzuki and the elusive “other” director, Isao Takahata – over the course of approximately one year as the studio rushes to complete their two highly anticipated new films, Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Takahata’s The Tale of The Princess Kaguya. The result is a rare glimpse into the inner workings of one of the most celebrated animation studios in the world, and a portrait of their dreams, passion and dedication that borders on madness. DIRECTOR: MAMI SUNADA Born in 1978, Mami Sunada studied documentary filmmaking while at Keio University before apprenticing as a director’s assistant under Hirokazu Kore-eda and others. -

Inspirációm: Japán Kultúra És Hagyomány Tükröződése a Japán Gyerekkönyvekben És Játékokban

Nagy Diána Inspirációm: Japán Kultúra és hagyomány tükröződése a japán gyerekkönyvekben és játékokban Doktori Értekezés Témavezető: Molnár Gyula MOME Doktori Iskola Budapest, 2013 Tartalomjegyzék Japán játékok a 20� század előtt �����������������������������������������������������������48 Babák �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 50 Bevezetés ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Állatok és egyéb játékok �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 51 Japán adottságai, rövid földrajzi áttekintése ����������������������������������������������7 Trükkös játékok ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 52 Japán rövid történelmi áttekintése �������������������������������������������������������������7 Kerekeken guruló játékok ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 52 Rövid művészettörténeti áttekintés �������������������������������������������������������������8 Csoportosan játszható játékok ������������������������������������������������������������������ 53 Japán kerámiaművesség és szobrászat ��������������������������������������������������������� 8 Fejlődés a játékgyártásban ��������������������������������������������������������������������56 Japán festészet és fametszés ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 A műanyag elterjedése Japánban és a világban ������������������������������������������� -

![I'm Going to Be Posting Some Excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview from the Char' Counterattack Fan Club Book.Forrefer[...]"](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6918/im-going-to-be-posting-some-excerpts-from-the-hideki-anno-yoshiyuki-tomino-interview-from-the-char-counterattack-fan-club-book-forrefer-1776918.webp)

I'm Going to Be Posting Some Excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino Interview from the Char' Counterattack Fan Club Book.Forrefer[...]"

Thread by @khodazat: "I'm going to be posting some excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino interview from the Char' Counterattack Fan Club Book.Forrefer[...]" I'm going to be posting some excerpts from the Hideki Anno/Yoshiyuki Tomino interview from the Char's Counterattack Fan Club Book. For reference, the book (released in 1993) wasbasically a doujinshi put together by Hideaki Anno. Beyond the Tomino interview... SGUNDAMIc CHAR'S,COUNDBRS vi Pi +h Panis, BMAF ; th A / mill FR HB*QILUES Rees PROUPT ua FS ROS +EtP—BS Awi— AFI GHA wr TF Pill im LTRS cos8 DHS RMS ShyuyIah mAETIX Rw KA @ TPLPGS) eS PAI BHF2 MAHSEALS GHos500S3Ic\' LUDTIA SY LAU PSSEts ‘= nuun MEFS HA ...1t compiles statements on the film by industry members like Toshio Suzuki, Mamoru Oshii, Haruhiko Mikimoto, Masami Yuki and many more. It's rare and expensive (ranges from $200-500 for a copy) so I haven't read any of it beyond the Tomino interview that was posted online. Also the interview is REALLY LONGso I'm only going to post the excerpts that interest me, not the whole thing. Okay, so withall that out of the way, here's the first excerpt. Anno:So, you know,| really love Char’s Counterattack. Tomino: (bewildered) Oh, thank you. Anno:| waspart of the staff, but even though | looked overall the storyboards,thefirst time | saw it | didn’t really getit. It wasn't until | experienced working as a director in the industry that| felt like | understood. Oguro:It turns out a lot of industry people enjoyed Char’s Counterattack.