Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB issue 27: November -December 2001 FILM FESTIVAL OF CATALUNYA AT SITGES Fresh from Japan: Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin The International Film Festival of Catalunya (October 4 - 13) held at Sitges - the charming seaside village just south of Barcelona, infused with life from the international gay community - this year again presented a mix of mainstream and fantastic film. (The festival's original title was Festival of Fantastic Cinema.) The more mainstream section (called Gran Angular ) showed 12 films only as opposed to the large offering of 27 films in the Fantastic section, evidence that this genre still predominates even though it is no longer exclusive. Japan made a big showing this year in both categories. Two feature-length animated films caught the attention of Sara Martin , an English literature teacher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and anime fan, who reports here on the latest offerings by two of Japan's most outstanding anime film makers, and gives us both a wee history and future glimpse of the anime genre - it's sure not kids' stuff and it's not always pretty. Japanese animated feature films are known as anime. This should not be confused with manga , the name given to the popular printed comics on which anime films are often based. Western spectators raised in a culture that identifies animation with cartoon films and TV series made predominately for children, may be surprised to learn that animation enjoys a far higher regard in Japan. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Performing and Contextualising the Late Piano Works of Akira Miyoshi: a Portfolio of Recorded Performances and Exegesis

Performing and contextualising the late piano works of Akira Miyoshi: a portfolio of recorded performances and exegesis Tomoe Kawabata Portfolio of recorded performances and exegesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ...... Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide May 2016 Table of Contents Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi Format of the Submission vii List of Musical Examples viii List of Tables and Graphs xii Part A: Sound Recordings Contents of CD 1 2 Contents of CD 2 3 Contents of CD 3 4 Contents of CD 4 5 Part B: Exegesis Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Background, formal structure and musical elements 35 1.1 Miyoshi’s compositional approach for solo piano in his early years 35 1.2 Miyoshi’s late works 44 Chapter 2 Understanding Miyoshi’s treatment of musical elements 69 2.1 Tempo shifts 69 2.2 Phrasing and rhythmic techniques 79 2.3 Dynamic shifts and the unification of musical elements 86 Chapter 3 Dramatic shaping of En Vers 92 3.1 Opening tempo 92 3.2 Phrase length 93 3.3 Quickening of tempo 94 3.4 Melody 94 ϯ͘ϱZŚLJƚŚŵŝĐƐĞŶƐĞϵϱ ϯ͘ϲdŚĞĞŶƚƌĂŶĐĞŽĨůŽƵĚĚLJŶĂŵŝĐƐϵϱ ϯ͘ϳdĞŵƉŽĂŶĚƌŚLJƚŚŵŝŶĐůŝŵĂĐƚŝĐƐĞĐƚŝŽŶƐϵϲ ϯ͘ϴdĞŵƉŽŽĨƚŚĞƌĞƉƌŝƐĞϵϲ ϯ͘ϵ^ŚŽƌƚĞŶŝŶŐŽĨƉŚƌĂƐĞƐϵϳ ŽŶĐůƵƐŝŽŶ ϵϴ >ŝƐƚŽĨ^ŽƵƌĐĞƐ ͗DƵƐŝĐĂůƐĐŽƌĞƐϭϬϯ ͗ŝƐĐŽŐƌĂƉŚLJϭϬϲ ͗ŝďůŝŽŐƌĂƉŚLJϭϬϵ NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. The CDs must be listened to in the Music Library. Abstract While the music of Japanese composer Akira Miyoshi (1933-2013) has become well- known within Japanese musical circles in the past 20 years, it has yet to achieve international recognition. -

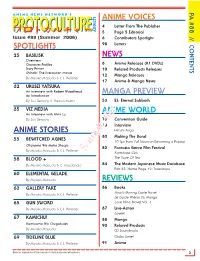

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Release of Episodes 7 to 12 of VLADLOVE, Mamoru Oshii and Junji

Make The World More Sustainable March 3, 2021 Ichigo Ichigo Animation Release of Episodes 7 to 12 of VLADLOVE, Mamoru Oshii and Junji Nishimura’s New Anime Series on March 14, 2021! Introducing Images from the Second Half of the Series! Renowned anime director Mamoru Oshii is known for breakthrough works such as PATLABOR: The Movie and Ghost in the Shell. VLADLOVE, written and directed by Oshii, is his first collaboration with Junji Nishimura since Urusei Yatsura, and Episodes 1 to 6 were released on February 14, 2021. Oshii’s strong desire to make a powerful, lasting impact is evident in the series. In the second half of VLADLOVE, Oshii stays true to his words “I will show you what happens when an old fogey gets cranky,” and pushes his art to another level. Enjoy VLADLOVE, a work which is rocking the foundations of modern Japanese anime. * Please see below the streaming platforms where you can watch VLADLOVE. 1 A Complete VLADLOVE Guide (in Japanese) Will Go on Sale on March 5, 2021! Currently Accepting Advanced Orders! How did a comedy about a high school girl and a beautiful vampire come to life? In VLADLOVE, Oshii weaves in many references to his works over the past decades. What was the intention behind that scene? What was the inspiration for that character? The guide answers these questions and more, offering a behind-the-scenes look into the production process. Illustration Gallery, Main Character Introductions and Images, Explanations of All Episodes, Cast Interviews, Storyboards of All Episodes, Images Selected by the Key Animation -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Katsu! 1 by Mitsuru Adachi Mitsuru Adachi

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Katsu! 1 by Mitsuru Adachi Mitsuru Adachi. Mitsuru Adachi ( あだち充 or 安達 充 , Adachi Mitsuru ? ) is a mangaka born February 9, 1951 in Isesaki, Gunma Prefecture, Japan. [1] After graduating from Gunma Prefectural Maebashi Commercial High School in 1969, Adachi worked as an assistant for Isami Ishii. [2] He made his manga debut in 1970 with Kieta Bakuon , based on a manga originally created by Satoru Ozawa. Kieta was published in Deluxe Shōnen Sunday (a manga magazine published by Shogakukan) . Adachi is well known for romantic comedy and sports manga (especially baseball) such as Touch , H2 , Slow Step , and Miyuki . He has been described as a writer of "delightful dialogue", a genius at portraying everyday life, [3] "the greatest pure storyteller", [4] and "a master mangaka". [5] He is one of the few mangaka to write for shōnen, shōjo, and seinen manga magazines, and be popular in all three. His works have been carried in manga magazines such as Weekly Shōnen Sunday , Ciao , Shōjo Comic , Big Comic , and Petit Comic , and most of his works are published through Shogakukan and Gakken. He was one of the flagship authors in the new Monthly Shōnen Sunday magazine which began publication in June 2009. Only two short story collections, Short Program and Short Program 2 (both through Viz Media), have been released in North America. He modelled his use of あだち rather than 安達 after the example of his older brother Tsutomu Adachi. In addition, it has been suggested that the accurate portrayal of sibling rivalry in Touch may come from Adachi's experiences while growing up with his older brother. -

Watch Deadman Wonderland Online

1 / 2 Watch Deadman Wonderland Online Bloody Hell—this is what Deadman Wonderland literally is! ... List of Elfen Lied episodes Very rare Lucy/Nyu & Nana figures from Elfen Lied. ... Dream Tech Series Elfen Lied Lucy & Nyu figures with extra faces set. at the best online prices at …. Watch Deadman Wonderland online animestreams. Other name: デッドマン・ワンダーランド. Plot Summary: Ganta Igarashi has been convicted of a crime that .... AnimeHeaven - watch Deadman Wonderland OAD (Dub) - Deadman Wonderland OVA (Dub) Episode anime online free and more animes online in high quality .... Deadman wonderland episode 1 english dubbed. Deadman . Crunchyroll deadman wonderland full episodes streaming online for free.Dead man wonderland .... Watch Deadman Wonderland 2011 full Series free, download deadman wonderland 2011. Stars: Kana Hanazawa, Greg Ayres, Romi Pak.. BOOK ONLINE. Kids go free before 12 ... Pledge your love as your nearest and dearest watch, with the Canadian Rockies as your witness. Then, head inside for .... [ online ] Available http://csii.usc.edu/documents/Nationalisms of and against ... ' Deadman Wonderland .... Nov 2, 2020 — This show received positive comments from the viewers. However, does it mean there will be a second season? Gandi Baat 5 All Episodes Free ( watch online ) #gandi_baat #webseries tags ... Watch Deadman Wonderland Online English Dubbed full episodes for Free.. Best anime series you can watch in 2021 Apr 09, 2014 · 1st 2 Berserk Films Stream on Hulu for 1 Week. Berserk: The ... Deadman Wonderland (2011). Ganta is .... 2 hours ago — Just like Sword Art Online these 5 are ... 1 year ago. 1,252,109 views. Why DEADMAN WONDERLAND isn't getting a Season 2. -

Review of the Scottish Animation Sector

__ Review of the Scottish Animation Sector Creative Scotland BOP Consulting March 2017 Page 1 of 45 Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 4 2. The Animation Sector ........................................................................ 6 3. Making Animation ............................................................................ 11 4. Learning Animation .......................................................................... 21 5. Watching Animation ......................................................................... 25 6. Case Study: Vancouver ................................................................... 27 7. Case Study: Denmark ...................................................................... 29 8. Case Study: Northern Ireland ......................................................... 32 9. Future Vision & Next Steps ............................................................. 35 10. Appendices ....................................................................................... 39 Page 2 of 45 This Report was commissioned by Creative Scotland, and produced by: Barbara McKissack and Bronwyn McLean, BOP Consulting (www.bop.co.uk) Cover image from Nothing to Declare courtesy of the Scottish Film Talent Network (SFTN), Studio Temba, Once Were Farmers and Interference Pattern © Hopscotch Films, CMI, Digicult & Creative Scotland. If you would like to know more about this report, please contact: Bronwyn McLean Email: [email protected] Tel: 0131 344 -

A Blue Cat on the Galactic Railroad: Anime and Cosmic Subjectivity

PAUL ROQUET A Blue Cat on the Galactic Railroad: Anime and Cosmic Subjectivity L OOKING UP AT THE STARS does not demand much in the way of movement: the muscles in the back of the neck contract, the head lifts. But in this simple turn from the interpersonal realm of the Earth’s surface to the expansive spread of the night sky, subjectivity undergoes a quietly radical transformation. Social identity falls away as the human body gazes into the light and darkness of its own distant past. To turn to the stars is to locate the material substrate of the self within the vast expanse of the cosmos. In the 1985 adaptation of Miyazawa Kenji’s classic Japanese children’s tale Night on the Galactic Railroad by anime studio Group TAC, this turn to look up at the Milky Way comes to serve as an alternate horizon of self- discovery for a young boy who feels ostracized at school and has difficulty making friends. The film experiments with the emergent anime aesthetics of limited animation, sound, and character design, reworking these styles for a larger cultural turn away from social identities toward what I will call cosmic subjectivity, a form of self-understanding drawn not through social frames, but by reflecting the self against the backdrop of the larger galaxy. The film’s primary audience consisted of school-age children born in the 1970s, the first generation to come of age in Japan’s post-1960s con- sumer society. Many would have first encountered Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad (Ginga tetsudo¯ no yoru; also known by the Esperanto title Neokto de la Galaksia Fervojo) as assigned reading in elementary school. -

S19-Seven-Seas.Pdf

19S Macm Seven Seas Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Vol. 9 by Shake-O The monster nurse will see you now! Welcome to the nurse's office! School Nurse Hitomi is more than happy to help you with any health concerns you might have. Whether you're dealing with growing pains or shrinking spurts, body parts that won't stay attached, or a pesky invisibility problem, Nurse Hitomi can provide a fresh look at the problem with her giant, all-seeing eye. So come on in! The nurse is ready to see you! Author Bio Shake-O is a Japanese artist best known as the creator of Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Seven Seas On Sale: Jun 18/19 5 x 7.12 • 180 pages 9781642750980 • $15.99 • pb Comics & Graphic Novels / Manga / Fantasy • Ages 16 years and up Series: Nurse Hitomi's Monster Infirmary Notes Promotion • Page 1/ 19S Macm Seven Seas Servamp Vol. 12 by Strike Tanaka T he unique vampire action-drama continues! When a stray black cat named Kuro crosses Mahiru Shirota's path, the high school freshman's life will never be the same again. Kuro is, in fact, no ordinary feline, but a servamp: a servant vampire. While Mahiru's personal philosophy is one of nonintervention, he soon becomes embroiled in an ancient, altogether surreal conflict between vampires and humans. Author Bio Strike Tanaka is best known as the creator of Servamp and has contributed to the Kagerou Daze comic anthology. Seven Seas On Sale: May 28/19 5 x 7.12 • 180 pages 9781626927278 • $15.99 • pb Comics & Graphic Novels / Manga / Fantasy • Ages 13 years and up Series: Servamp Notes Promotion • Page 2/ 19S Macm Seven Seas Satan's Secretary Vol.