Concepts and Methods in Social Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016 Professor: Office: Office Phone: Office Hours: Email: Course Description and Learning Outcomes Comparative politics is perhaps the broadest field of political science. This course will introduce students to the major theoretical approaches employed in comparative politics. The major debates and controversies in the field will be examined. Although some associate comparative politics with “the comparative method,” those conducting research in the area of comparative politics use a multitude of methodologies and pursue diverse topics. In this course, students will analyze and discuss the theoretical approaches and methods used in comparative politics. Course Requirements Class participation and attendance. Students must come to class prepared, having completed all of the required reading, and ready to actively discuss the material at hand. Each student must submit comments/questions on the assigned readings for six classes (not including the class you help facilitate). Please e-mail them to me by noon on the day of class. Students are expected to attend each class. Missing classes will have a deleterious effect on this portion of the grade. Arriving late, leaving early, or interrupting class with a phone or other electronic device will also result in a drop in the student’s grade. Students are not allowed to sleep, read newspapers or anything else, listen to headphones, TEXT, or talk to others during class. You must turn off all electronic devices during class. Any exceptions must be cleared with me in advance. Laptop computers and iPads are allowed for taking notes ONLY. I reserve the right to ban laptops, iPads, and so forth. -

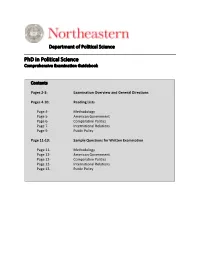

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Toward a More Democratic Congress?

TOWARD A MORE DEMOCRATIC CONGRESS? OUR IMPERFECT DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION: THE CRITICS EXAMINED STEPHEN MACEDO* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 609 I. SENATE MALAPPORTIONMENT AND POLITICAL EQUALITY................. 611 II. IN DEFENSE OF THE SENATE................................................................ 618 III. CONSENT AS A DEMOCRATIC VIRTUE ................................................. 620 IV. REDISTRICTING AND THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE REFORM? ................ 620 V. THE PROBLEM OF GRIDLOCK, MINORITY VETOES, AND STATUS- QUO BIAS: UNCLOGGING THE CHANNELS OF POLITICAL CHANGE?.... 622 CONCLUSION................................................................................................... 627 INTRODUCTION There is much to admire in the work of those recent scholars of constitutional reform – including Sanford Levinson, Larry Sabato, and prior to them, Robert Dahl – who propose to reinvigorate our democracy by “correcting” and “revitalizing” our Constitution. They are right to warn that “Constitution worship” should not supplant critical thinking and sober assessment. There is no doubt that our 220-year-old founding charter – itself the product of compromise and consensus, and not only scholarly musing – could be improved upon. Dahl points out that in 1787, “[h]istory had produced no truly relevant models of representative government on the scale the United States had already attained, not to mention the scale it would reach in years to come.”1 Political science has since progressed; as Dahl also observes, none of us “would hire an electrician equipped only with Franklin’s knowledge to do our wiring.”2 But our political plumbing is just as archaic. I, too, have participated in efforts to assess the state of our democracy, and co-authored a work that offers recommendations, some of which overlap with * Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values; Director of the University Center for Human Values, Princeton University. -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be -

A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Advance Access publication June 13, 2006 Political Analysis (2006) 14:227–249 doi:10.1093/pan/mpj017 A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research James Mahoney Departments of Political Science and Sociology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208-1006 e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) Gary Goertz Department of Political Science, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 e-mail: [email protected] The quantitative and qualitative research traditions can be thought of as distinct cultures marked by different values, beliefs, and norms. In this essay, we adopt this metaphor toward the end of contrasting these research traditions across 10 areas: (1) approaches to expla- nation, (2) conceptions of causation, (3) multivariate explanations, (4) equifinality, (5) scope and causal generalization, (6) case selection, (7) weighting observations, (8) substantively important cases, (9) lack of fit, and (10) concepts and measurement. We suggest that an appreciation of the alternative assumptions and goals of the traditions can help scholars avoid misunderstandings and contribute to more productive ‘‘cross-cultural’’ communica- tion in political science. Introduction Comparisons of the quantitative and qualitative research traditions sometimes call to mind religious metaphors. In his commentary for this issue, for example, Beck (2006) likens the traditions to the worship of alternative gods. Schrodt (2006), inspired by Brady’s (2004b, 53) prior casting of the controversy in terms of theology versus homiletics, is more explicit: ‘‘while this debate is not in any sense about religion, its dynamics are best understood as though it were about religion. We have always known that, it just needed to be said.’’ We prefer to think of the two traditions as alternative cultures. -

Achieving Cooperating Under Anarchy,” by Robert Axelrod and Robert Keohane, 1985

Devarati Ghosh “Achieving Cooperating Under Anarchy,” by Robert Axelrod and Robert Keohane, 1985 · Definitions: remember that for cooperation to occur, there must be some combination of conflicting and shared interests. Cooperation is distinct from harmony, where there is a total identity of interests between states. Anarchy is the absence of common world government, but it does not imply that the world is devoid of organizational forms. · Three dimensions of structure impact the incentives for states to cooperate: the mutuality of interests, the shadow of the future, and the number of players. The mutuality of interests—is determined by an objective structure of material payoffs, as well as upon actors’ perceptions of that structure. Changes in beliefs about other players, as well as about the most optimal policy, may cause state leaders to prefer unilateral action. This is true of both political-economic and security issues. · The longer the shadow of the future, the more the costs of defection offset the short-term incentive to defect. This is more true of political-economic issues, where there is a greater likelihood of extended interaction, than of security issues, where a successful preemptive war would seriously advantage one of the players. Also important is the ability of states to identifying defection, which Axelrod and Keohane believe does not distinguish political-economic issues from security ones. · Once defection has been identified, the next problem is sanctioning the cheater. This becomes significantly more difficult when there is a large number of actors. Defection can be costly, so there must be enough incentive for states to punish defectors. -

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010 Gary King, Robert Putnam, and Sidney Verba Thursdays 12-2pm, Littauer M-17 Gary King [email protected], http://GKing.Harvard.edu Phone: 617-495-2027 Office: 34 Kirkland Street Robert Putnam [email protected] Phone: 617-495-0539 Office: 79 JFK Street, T376 Sidney Verba [email protected] Phone: 617-495-4421 Office: Littauer Center, M18 Prerequisite or corequisite: Gov1000 Overview If you could learn only one thing in graduate school, it should be how to do scholarly research. You should be able to assess the state of a scholarly literature, identify interesting questions, formulate strategies for answering them, have the methodological tools with which to conduct the research, and understand how to write up the results so they can be published. Although most graduate level courses address these issues indirectly, we provide an explicit analysis of each. We do this in the context of a variety of strategies of empirical political inquiry. Our examples cover American politics, international relations, compara- tive politics, and other subfields of political science that rely on empirical evidence. We do not address certain research in political theory for which empirical evidence is not central, but our methodological emphases will be as varied as our substantive examples. We take empirical evidence to be historical, quantitative, or anthropological. Specific methodolo- gies include survey research, experiments, non-experiments, intensive interviews, statistical analyses, case studies, and participant observation. Assignments Weekly reading assignments are listed below. Since our classes are largely participatory, be sure to complete the readings prior to the class for which they are as- signed. -

Research Design Skopje 6-7 November 2008

Research Design Skopje 6-7 November 2008 Daniel Bochsler and Lucas Leemann Center for Comparative and International Studies, University of Zurich [email protected]; [email protected] Introduction The goal of this workshop session is to review the current literature on issues of research design in social sciences and to allow the participants to improve on their skills in designing research. The workshop starts off with a short review of some basic principles of scientific research, before turning to two of the main goals of scientific work, namely descriptive and causal inferences. In a second part different research designs are discussed, relying on the basic distinction between experimental and quasi-experimental work. Given that despite the important forays in experimental studies in the social sciences (see Druckman, Green, Kuklinski and Lupia, 2006) quasi- experimental designs will be discussed in more detail. Special emphasis will be put on the dangers to our inferences in such quasi-experimental designs. The third part will consist of a discussion of a few chosen research designs to highlight their strengths and weaknesses. Finally, based on the participants own experience, in a short training session they will have to sketch possible research designs for chosen research questions. Plan, readings and literature Most of the literature on which this workshop will rely comes from King, Keohane and Verba (1994), a book that, from a very specific perspective, highlights the similarities between quantitative and qualitative approaches. Needless to say, this book has attracted a series of critiques (e.g., Caporaso, 1995; Collier, 1995; Rogowski, 1995; Tarrow, 1995; Brady and Collier, 2004). -

Robert O. Keohane: the Study of International Relations*

Robert O. Keohane: The Study of International Relations* Peter A. Gourevitch, University of California, San Diego n electing Robert Keohane APSA I president, members have made an interesting intellectual statement about the study of international rela- tions. Keohane has been the major theoretical challenger in the past quarter century of a previous Asso- ciation president, Kenneth Waltz, whose work dominated the debates in the field for many years. Keo- hane's writings, his debate with Waltz, his ideas about institutions, cooperation under anarchy, transna- tional relations, complex interdepen- dence, ideas, and domestic politics now stand as fundamental reference points for current discussions in this field.1 Theorizing, methodology, exten- sion, and integration: these nouns make a start of characterizing the Robert O. Keohane contributions Robert Keohane has made to the study of international relations. Methodology —Keohane places concepts, techniques, and ap- Theorizing— Keohane challenges the study of the strategic interac- proaches as the broader discpline. the realist analysis that anarchy tion among states onto the foun- and the security dilemma inevita- dations of economics, game The field of international relations bly lead states into conflict, first theory, and methodological indi- has been quite transformed between with the concept of transnational vidualism and encourages the ap- the early 1960s, when Keohane en- relations, which undermines the plication of positivist techniques tered it, and the late 1990s, when his centrality -

"A Sea Change in Political Methodology." in Rethinking Social

Introduction to Rethinking Social Inquiry, 2 edn., Henry E. Brady, and David Collier, ed. (Rowman and Littlefield, 2010). A Sea Change in Political Methodology David Collier, Henry E. Brady, and Jason Seawright We begin with rival claims about the ''science'' in social science. In our view, juxtaposing these claims brings into focus a sea change in political science methodology. King, Keohane, and Verba's (KKV) 1994 book, Designing Social Inquiry, proposes a bold methodological agenda for researchers who work in the qualitative tradition. The book's subtitle directly summarizes the agenda: ''scientific inference in qualitative research'' (italics added). To its credit, the book is explicit in its definition of science. It draws on what we and many others have viewed as a ''quantitative template,'' which serves as the foun- dation for the desired scientific form of qualitative methods. In KKV's view, standard research procedures of qualitative analysis are routinely problem- atic, and ideas drawn from conventional quantitative methods are offered as guideposts to help qualitative researchers be scientific. 1. For our own work, we share Freedman's view of plurality in scientific methods, and we recognize social versus natural science as partially different enterprises. Yet the two can and should strive for careful formulation of hypotheses, intersubjec- tive agreement on the facts being analyzed, precise use of data, and good research design. With this big-tent understanding of science, we are happy to be included in the tent. 2. As explained above in the preface, in the second edition we use the abbreviation KKV to refer to the book, rather than DSI, as in the first edition. -

Introduction to the Second Edition

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title A Sea of Change in Political Methodology? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8gq6g191 Journal Qualitative and Multi-Method Research, 9(1) Authors Collier, David Brady, Henry E Seawright, Jason Publication Date 2011-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Qualitative and Multi-Method Research. Newsletter of the American Political Science Association Organized Section. 9, No. 1 (Spring 2011, forthcoming). A Sea Change in Political Methodology1 David Collier University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Henry E. Brady University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Jason Seawright Northwestern University [email protected] Shifting debates on what constitutes “science” reveal competing claims about methodology.2 Of course, in its origin the term “science” means “knowledge,” and researchers obviously hold a wide spectrum of positions on how to produce viable knowledge. Within this spectrum, we compare two alternative meanings of science, advanced by scholars who seek to legitimate sharply contrasting views of qualitative methods. This comparison points to a sea change in political science methodology.3 1 This article draws on the Introductions to Parts I and II of Brady and Collier, Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards, 2nd edn. (Lanham, MD.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010). 2 Morgan (1996) provides a broad overview of rival views of science, encompassing the natural, -

International Institutions

Political Science International Institutions Yukari Iwanami 330 Harkness Hall [email protected] Office Hours: TBA Course Description This course will address questions such as why international organizations exist, whether they affect the behavior of states, how members’ domestic factors affect the decision-making process of an organization, and how power differences among states influence policy implementation of an international organization. The ultimate goal is to help students form their own opinions on the roles of formal organizations in international politics, the influence of major powers on interna- tional organizations, and their problems and limitations. We will read existing literature ranging from traditional approaches to empirical analyses, and focus on the problem of cooperation under anarchy, availability of outside options and lack of enforcement power, the issues of delegation, and the effects of voting rules and organizational membership on the decision-making process. Required Books • Robert Keohane, After Hegemony, Princeton University Press, 1984 • Lisa Martin and Beth Simmons eds. International Institutions. MIT Press, 2001 1 Introduction • J. Martin Rochester. 1986. “The Rise and Fall of International Organization as a Field of Study,” International Organization 40(4), 777-813 • Cheryl Shanks, Harold K. Jocobson, and Jeffrey H. Kaplan, Inertia and Change in the Con- stellation of International Governmental Organizations, 1981-1992, in Martin and Simmons 1 2 Problems under Anarchy This section addresses problems inherent in world politics. We discuss issues such as collective action problem, availability of outside options, power differences among states, and lack of en- forcement power. • Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action, chapter 1 and 2 • Garrett Hardin, 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, 1243-48 • Eric Voeten, 2001, “Outside Options and the Logic of Security Council Action”, American Political Science Review, 95, 845-858 • James D.