Priorities and Challenges of Qatar's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E Me Rg Ency F Ood a Ss Is Ta

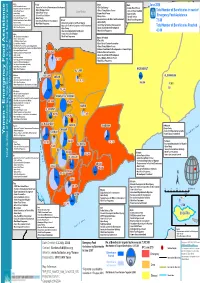

Amran Sa'ada Sana'a Marib d June 2016 e - CARE International Yemen - Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development - Civil Confederacy - Islamic Relief Yemen n - Enjaz foundation fpr development - Danish Refugee Council c - Islamic Relief Yemen - Global ChangeMakers Yemen a Saudi Arabia - Life and Peace Coalition Total Number of Beneficiaries in need of - Qatar Charity - Islamic Relief Yemen - Islamic Relief Yemen - Qatar Charity y n - Life and Peace Coalition - Life and Peace Coalition t - Mercy Corps Æ Emergency Food Assistance i - Sama Al Yemen c - Norwegian Refugee Council - Qatar Charity r a - Responsiveness for Relief and Development - Oxford Committee for Famine Relief - Sanid Org. for Relief and Development Al Jawf - World Food Programme u 7.6 M t - Sama Al Yemen - Adventist Development and Relief Agency - Qatar Charity c - World Food Programme - Social Association for Development - Sanid Org. for Relief and Development s - Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development e - World Food Programme Total Number of Beneficiaries Reached i - Qatar Charity - Social Association for Development S - International Organization for Migration - World Food Programme 4.0 M s d Hajjah - Islamic Help United Kingdom s o - Abs Development Organization - World Food Programme Amanat Al Asimah o - Action Contra La Faim 6 - Direct Aid A - CARE International Yemen F 1 - Life and Peace Coalition - Bunia Social Charities Association e - Life Flow for Peace & Development Organization 0 - Global ChangeMakers Yemen d h - National Foundation for Development and Human Rights 2 t - National Foundation for Development and Human Rights - Norwegian Refugee Council o - National Prisoner Foundation e SA'ADA y - Oxford Committee for Famine Relief - Qatar Charity n b - Social Association for Development o - Relief International u 5% - United Nations Children's Fund d - Sanid Org. -

Philanthropy Law Report

QATAR Philanthropy Law Report International Center for Not-for-Profit Law 1126 16th Street, NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 452-8600 www.icnl.org Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Recent Developments ..................................................................................................................... 3 Relevant Laws ................................................................................................................................. 5 Constitutional Framework .............................................................................................................. 5 National Laws and Regulations Affecting Philanthropic Giving ...................................................... 5 Analysis ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Organizational Forms for Nonprofit Organizations ...................................................................... 10 Registration of Domestic Nonprofit Organizations ...................................................................... 11 Registration of Foreign Nonprofit Organizations ......................................................................... 16 Nonprofit Organization Activities ................................................................................................. 16 Termination, Dissolution, and Sanctions ..................................................................................... -

Origination, Organization, and Prevention: Saudi Arabia, Terrorist Financing and the War on Terror”

Testimony of Steven Emerson with Jonathan Levin Before the United States Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs “Terrorism Financing: Origination, Organization, and Prevention: Saudi Arabia, Terrorist Financing and the War on Terror” July 31, 2003 Steven Emerson Executive Director The Investigative Project 5505 Conn. Ave NW #341 Washington DC 20015 Email: [email protected] phone 202-363-8602 fax 202 966 5191 Introduction Terrorism depends upon the presence of three primary ingredients: Indoctrination, recruitment and financing. Take away any one of those three ingredients and the chances for success are geometrically reduced. In the nearly two years since the horrific attacks of 9/11, the war on terrorism has been assiduously fought by the US military, intelligence and law enforcement. Besides destroying the base that Al Qaeda used in Afghanistan, the United States has conducted a comprehensive campaign in the United States to arrest, prosecute, deport or jail those suspected of being connected to terrorist cells. The successful prosecution of terrorist cells in Detroit and Buffalo and the announcement of indictments against suspected terrorist cells in Portland, Seattle, northern Virginia, Chicago, Tampa, Brooklyn, and elsewhere have demonstrated the resolve of those on the front line in the battle against terrorism. Dozens of groups, financial conduits and financiers have seen their assets frozen or have been classified as terrorist by the US Government. One of the most sensitive areas of investigation remains the role played by financial entities and non-governmental organizations (ngo’s) connected to or operating under the aegis of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Since the July 24 release of the “Report of the Joint Inquiry into the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001,” the question of what role Saudi Arabia has played in supporting terrorism, particularly Al Qaeda and the 9/11 attacks, has come under increasing scrutiny. -

Qatar Charity in Niger: Biopolitics of an International Islamic NGO

WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 73 Qatar Charity in Niger: Biopolitics of an international Islamic NGO Chloe Dugger [email protected] February 2011 Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford Working Paper Series The Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series is intended to aid the rapid distribution of work in progress, research findings and special lectures by researchers and associates of the RSC. Papers aim to stimulate discussion among the worldwide community of scholars, policymakers and practitioners. They are distributed free of charge in PDF format via the RSC website. Bound hard copies of the working papers may also be requested from the Centre. The opinions expressed in the papers are solely those of the author/s who retain the copyright. They should not be attributed to the project funders or the Refugee Studies Centre, the Oxford Department of International Development or the University of Oxford. Comments on individual Working Papers are welcomed, and should be directed to the author/s. Further details may be found at the RSC website (www.rsc.ox.ac.uk). The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect RSC views. RSC does not warrant in anyway the accuracy of the information quoted and may not be held liable for any loss caused by reliance on the accuracy or reliability thereof. RSC WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 73 2 Contents List of Figures 4 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 5 Glossary 5 1 Introduction 6 Contribution of the study 7 Structure of the -

List of Participants by Organization

2014 ANNUAL WFP PARTNERSHIP CONSULTATION List of participants by organization: ACTIONAID Mr. Bijay Kumar Country Director for ActionAid Kenya Mr. John Abuya Head of International Humanitarian Action and Resilience Team Donna Muwonge Multilateral Partnerships Manager – International Partnership Development ACTED Mr. Luca Pupulin Director of Programmes ACTION CONTRE LA FAIM Mr. Mike Penrose Executive Director Mr. Vincent Taillandier Director of Operations ADRA Mr. Frank Teeuwen Director, United Nations Liaison Officer AGA KHAN DEVELOPMENT NETWORK Mr. Aly Nazerali CEO and Senior Advisor for Policy, Communications and Institutional Relations Mr. Najmi Kanji Programme Director, Special Programmes AVSI Mr. Alberto Piatti Secretary General Ms. Maria Teresa Gatti Knowledge Center & Communication Manager BASIC EDUCATION AND EMPLOYABLE Mr. Hamish Khan Managing Director SKILL TRAINING (BEST) THE CASH LEARNING PARTNERSHIP Ms. Sara Almer Coordinator (CALP) Ms. Nadia Zuodar Technical Coordinator 2014 ANNUAL WFP PARTNERSHIP CONSULTATION CANADIAN FOODGRAINS BANK Mr. Jim Cornelius Executive Director CANADIAN HUNGER FOUNDATION Mr. Stewart Hardacre President & CEO (CHF) Ms. Adair Heuchan Board Director CARE CANADA Ms. Jacquelin Wright Vice President of International Programs Ms. Jessie Thomson Director, Humanitarian Assistance and Emergency Team CARE USA Mr. Justus Liku Senior Advisor for Emergency Food and Nutrition Security CARITAS INTERNATIONALIS Ms. Floriana Polito Humanitarian Policy Officer CONCERN WORLDWIDE Mr. Dominic MacSorley CEO Ms. Olive Towey Head of Advocacy COORDINADORA ONG PARA EL Mr. François Parnaud ACF - WFP HQ contract referent DESARROLLO ESPANA Mr. Vincent Stehli Director of Operations, ACF Spain Mr. Julien Jacob Food Security and Livelihoods Advisor, ACF Spain DANISH REFUGEE COUNCIL Mr. Rasmus Stuhr Jakobsen Chief, Division of Emergency Safety and Supply FOCUS HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE Mr. -

STRATEGIC EVALUATION FAO/WFP Joint Evaluation of Food Security Cluster Coordination in Humanitarian Action

measuring results, sharing lessons results, measuring sharing STRATEGIC EVALUATION FAO/WFP Joint Evaluation of Food Security Cluster Coordination in Humanitarian Action A Strategic Evaluation Evaluation Report August 2014 Prepared by Julia Steets, Team Leader; James Darcy, Senior Evaluator; Lioba Weingärtner, Senior Evaluator; Pierre Leguéné, Senior Evaluator Commissioned by the FAO and WFP Offices of Evaluation Report number: OEV/2013/012 Acknowledgements The evaluation team would like to thank all of those who provided support and input for this evaluation. We are particularly grateful for the clear guidance and constructive cooperation of the evaluation managers, the extensive support of the Food Security Cluster’s Global Support Team, the input and feedback of the Reference Group, the excellent facilitation of all of our country missions by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the many individuals working for the United Nations, and the international and national NGOs and governments that provided their time and insights by participating in the survey and in interviews. Our special thanks go to Rahel Dette and Maximilian Norz, who provided valuable research support. Disclaimer The opinions expressed are those of the Evaluation Team, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) or the World Food Programme (WFP). Responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the authors. Publication of this document does not imply endorsement by FAO or WFP of the opinions expressed. The designations employed and the presentation of material in the maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO or WFP concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory or sea area, or concerning the delimitation of frontiers. -

20201231 Irq 2020 Humanitari

IRAQ 2020 Humanitarian Funding Overview As of 31 December 2020 US$662.2M US$609.1¹ (US$99.6M) TOTAL HRP & COVID-19 FUNDING RECEIVED FOR COVID-19 FUNDING RECEIVED FUNDING REQUIREMENTS 92% HRP & COVID-19 as of 31 December 2020 (US$264.8M) FUNDED US$53.1M (US$165.2M) TOTAL COVID-19 COMPONENT8 HRP & COVID-19 UNMET COVID-19 FUNDING UNMET REQUIREMENTS as of 31 December 2020 BY CLUSTER FOR HRP & COVID-19 (US$) US$846.6M TOTAL FUNDING RECEIVED Cluster Funding received Overall HRP & COVID Requirements as of 31 December 2020 Total COVID-199 Received Gap Total COVID-199 US$609.1M HRP & COVID-19 FUNDING THROUGH 2020 HRP CCCM 4.2M (0.6M) 25.6M (24.2M) 71.9% 28.1% US$237.5M Education 9.8M (0.4M) 30.9M (2.6M) FUNDING OUTSIDE 2020 HRP & COVID-19² 25.9M (10.2M) EL 18.3M (2.0M) BY STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES (SO)4 SO1 SO2 Combined FSC 31.6M (5.8M) 83.1M (21.2M) 3% ADDITIONAL COVID-19 REQUEST³ Health 42.4M (21.6M) 103.8M6 (65.4M) Protection, $519.8 $142.4 34.8M (0.8M) 97.7M (53.5M) 48% million HLP &MA million 49% CP 14.0M (3.3M) 39.2M (5.1M) 20.1M (5.2M) 31.6M (12.6M) COVID-19 COMPONENT GBV ($122.4M) WITHIN SO1 & SO2 Shelter/NFI 8.1M (0M) 50.8M (7.6M) BREAKDOWN OF CASH FUNDING REQUESTS BY CLUSTER5 24.7M WASH (5.4M) 52.0M (19.4M) 3% 2% 0.02% 7% MPCA 10.9M (8.0M) 86.2M (43.0M) 12% $213 41% CCS 6.5M - 15.0M - million Not specified 323.9M (34.2M) 77.7M 34% MPCA FS Protection EL Multiple clusters 59.9M (12.4M) 14.1M WASH SNFI Education BY DONOR (US$) (TOP TEN DONORS) US$609.1 million HRP FUNDING RECEIVED 330.7M $ HRP Funding BY PARTNER TYPE 4% 3% 6% 15% 71 partners7 49.3M 37.7M 34.9M 72% 25.7M 19.6M 16.4M 16.0M 9.1M 9.0M INGO UN NNGO European United USA Germany Canada Commission Japan Norway Australia Kingdom Netherlands Kuwait Pooled fund IO 1. -

Sports for Peace and Development

صدقاتكم نوصلها هدايا للمستحقين We Deliver it Your Sadaqah to Those Most is a Gift Deserving + 250,000 مستفيد ًسنويا +100,000 Beneficiaries مستخدم Users Per Year RACA License No: 904/2019 اآلن يمكنــك أن تطلــب مــن مكانــك خدمــة المحصــل المنزلــي لتحصيــل تبرعــك عبــر مســح رمــز QR مــن جوالــك NOW We Come to Your Home Now Scan QR Code to Request a QC Representative طرق التبرع qcharity.org 44667711 qch.qa.app Qatar Charity is a leading Dignity international non-gov- for All ernmental organization working in the field of hu- manitarian aid and devel- opment since 1992; and was established in compliance with the laws regulating the non-profit sector in the State of Qatar. الخيرية قطر عن تصدر دورية مجلة دورية تصدر عن قطر الخيرية Editorial وعشرونby Qatar Charity أثنانMagazine العدد Periodic هـ 1441 23 رمضان.Issue No م 2020 أبريل أبريل Muharram 1442 AH - September 2020 The new issue of the “Ghiras” magazine comes out while the GENERAL SUPERVISOR coronavirus pandemic is still a serious threat to humankind across AHMED AL-ALI the globe, which has posed further challenges to humanitarian and charitable organizations in delivering services to the affected. Editor - in - Chief In this issue, readers will find a doctor, infected with COVID-19, Ali AL-RASHID from Qatar Charity’s field teams, setting an example in humanitarian action by continuing his work remotely despite the Managing Editor complications of the infection. TAMADOR AL-QADI It should also be noted that the pandemic could not prevent these institutions from carrying out their humanitarian duties at the EDITOR - CUM- TRANSLATOR time of certain crises like the massive explosion that has rocked MOHAMMAD ATAUR RAB the port area of Beirut. -

Resource Mobilization Strategy 2019-2021 2 Resource Mobilization Strategy 2019-2021 United Nations Relief and Works Agency 3

united nations relief and works agency 1 resource mobilization strategy 2019-2021 2 resource mobilization strategy 2019-2021 united nations relief and works agency 3 resource mobilization strategy 2019-2021 4 resource mobilization strategy 2019-2021 © 2019 UNRWA About UNRWA UNRWA is a United Nations agency established by the General Assembly in 1949 and mandated to provide assistance and protection to some 5.4 million registered Palestine refugees. Its mission is to help Palestine refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and the Gaza Strip achieve their full human development potential, pending a just and lasting solution to their plight. UNRWA services encompass education, health care, relief and social services, camp infrastructure and improvement, and microfinance. Cover photo: Palestine refugee students at the UNRWA Jalazone Girls’ School in the West Bank. © 2018 UNRWA Photo by Marwan Baghdadi united nations relief and works agency 5 acronyms and abbreviations AOR Annual Operations Report UNGA United Nations General Assembly ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations UNSG United Nations Secretary-General AU African Union WBG World Bank Group BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa WBMDTF World Bank Multi Donor Trust Fund CEAPAD Cooperation among East Asian Countries for Palestinian Development CERF UN Central Emergency Response Fund CIS Commonwealth of Independent States CSO Civil Society Organization EU European Union ERCD External Relations and Communication Department IDB Islamic Development Bank IFIs International -

Qatar Charity and the United Nations Download

Editorial In accordance with its vision and mission, Qatar Charity has realized since its inception the impor- tance of cooperation and building strategic partnerships with United Nations and international organizations to address the challenges of development and humanitarian work worldwide. This has become increasingly important as the world has witnessed an increase in the numbers of displaced people and refugees in recent years due to the outbreak of armed conflicts in many regions. This un- derlines the need for coordination with the humanitarian actors in various fields of relief work. This way, Qatar Charity has become an integral part of the international humanitarian system, seeking to serve and provide a decent life for every human being, and protect them from the grave effects of ignorance, poverty and violence. We have therefore decided to dedicate the editorial of this issue of Ghiras Magazine to highlighting Qatar Charity’s impressive record of achievements in the field of cooperation with international and UN organizations. In this regard, 93 cooperation and partnership protocols have been signed with 28 countries by the end of July this year, including 11 strategic cooperation agreements worth USD 126 million. The topics and facts discussed in this feature highlight how these partnerships contributed to the success of Qatar Charity in implementing large-scale integrated development programs such as the “Food Security” project and contributing to combating poverty and mitigating the effects of famine and drought in Niger over a period of seven years (2010 – 2017). These partnerships also reflect in Qatar Charity’s ranking first for several years among international humanitarian NGOs providing re- lief aid to the Syrian people, according to the Financial Tracking Service (FTS) report of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). -

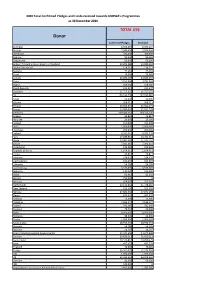

Total Confirmed Pledges and Funds Received Towards UNRWA's Programmes As 30 December 2020

2020 Total Confirmed Pledges and Funds received towards UNRWA's Programmes as 30 December 2020 TOTAL US$ Donor Confirmed Pledges Received Australia 8,393,204 8,393,204 Austria 5,049,494 5,049,494 Azerbaijan 300,000 300,000 Bahrain 50,000 50,000 Bangladesh 50,000 50,000 Belgium (including Government of Flanders) 13,203,288 13,080,662 Brunei Darussalam 114,712 114,712 Bulgaria 77,263 77,263 Brazil 75,000 75,000 Canada 24,083,407 24,083,407 China 3,291,904 3,291,904 Cyprus 168,000 168,000 Czech Republic 231,547 231,547 Denmark 15,717,155 15,717,155 EU 156,534,758 137,105,481 Egypt 20,000 20,000 Estonia 308,911 308,911 Finland 10,352,571 10,352,571 France 22,986,067 22,915,709 Germany 209,046,062 169,376,106 Greece 44,867 44,867 Holy See 20,000 20,000 Iceland 315,039 315,039 India 5,000,000 5,000,000 Indonesia 200,000 200,000 Ireland 8,933,341 8,933,341 Italy 17,689,912 16,431,612 Japan 33,081,492 31,247,752 Jordan 7,392,615 7,392,615 Kazakhstan 100,000 100,000 Republic of Korea 1,164,611 1,164,611 Latvia 20,812 20,812 Lebanon 224,931 224,931 Liechtenstein 103,093 103,093 Lithuania 54,289 54,289 Luxembourg 5,572,075 5,572,075 Malaysia 120,000 120,000 Malta 83,910 83,910 Mexico 750,000 0 Monaco 609,007 322,269 Netherlands 22,130,814 21,738,460 New Zealand 595,300 595,300 Norway 27,882,558 27,871,193 Oman 432,637 432,637 Pakistan 13,690 13,690 Palestine 4,186,174 4,186,174 Poland 792,645 792,645 Portugal 79,737 20,000 Qatar 8,000,000 8,000,000 Romania 44,300 44,300 Russia 2,000,000 2,000,000 Saudi Arabia 28,933,333 28,933,333 Slovenia 54,289 -

Pakistan Initial Floods Emergency Response Plan As of 10 August 2010

SAMPLE OF ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN INTER-AGENCY COMMON HUMANTIARIAN ACTION PLANS ACF GOAL MACCA TEARFUND ACTED GTZ Malteser Terre des Hommes ADRA Handicap International Medair UNAIDS Afghanaid HELP Mercy Corps UNDP AVSI HelpAge International MERLIN UNDSS CARE Humedica NPA UNESCO CARITAS IMC NRC UNFPA CONCERN INTERSOS OCHA UN-HABITAT COOPI IOM OHCHR UNHCR CRS IRC OXFAM UNICEF CWS IRIN Première Urgence WFP DRC Islamic Relief Worldwide Save the Children WHO FAO LWF Solidarités World Vision International 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 Table I. Summary of Requirements – By Cluster ................................................................................... 4 2. CONTEXT AND HUMANITARIAN CONSEQUENCES.................................................................................... 5 2.1 CONTEXT AND RESPONSE TO DATE.............................................................................................................. 6 2.2 FUNDING TO DATE...................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 HUMANITARIAN CONSEQUENCES AND NEEDS ANALYSIS ................................................................................. 8 2.4 SCENARIOS ............................................................................................................................................. 10 3. COMMON HUMANTIARIAN ACTION PLAN ................................................................................................