Gangs, Race, and 'The Street' in Prison: an Inductive Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organised Crime Around the World

European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) P.O.Box 161, FIN-00131 Helsinki Finland Publication Series No. 31 ORGANISED CRIME AROUND THE WORLD Sabrina Adamoli Andrea Di Nicola Ernesto U. Savona and Paola Zoffi Helsinki 1998 Copiescanbepurchasedfrom: AcademicBookstore CriminalJusticePress P.O.Box128 P.O.Box249 FIN-00101 Helsinki Monsey,NewYork10952 Finland USA ISBN951-53-1746-0 ISSN 1237-4741 Pagelayout:DTPageOy,Helsinki,Finland PrintedbyTammer-PainoOy,Tampere,Finland,1998 Foreword The spread of organized crime around the world has stimulated considerable national and international action. Much of this action has emerged only over the last few years. The tools to be used in responding to the challenges posed by organized crime are still being tested. One of the difficulties in designing effective countermeasures has been a lack of information on what organized crime actually is, and on what measures have proven effective elsewhere. Furthermore, international dis- cussion is often hampered by the murkiness of the definition of organized crime; while some may be speaking about drug trafficking, others are talking about trafficking in migrants, and still others about racketeering or corrup- tion. This report describes recent trends in organized crime and in national and international countermeasures around the world. In doing so, it provides the necessary basis for a rational discussion of the many manifestations of organized crime, and of what action should be undertaken. The report is based on numerous studies, official reports and news reports. Given the broad topic and the rapidly changing nature of organized crime, the report does not seek to be exhaustive. -

2014 Deemster Geoffrey Tattersall QC

CAROLINE WEATHERILL MEMORIAL LECTURE 2014 A LITANY OF EXHUMATIONS 1 As you will all be aware the wall between heaven and hell which was liable to be maintained jointly fell into disrepair. St Peter asked the Devil to contribute to the cost of the necessary repairs but the Devil refused to pay anything. St Peter said to him if you don`t agree to contribute we will sue. Oh, said the Devil, and where are you going to find a lawyer. It may well be that the Isle of Man Law Society had a similar difficulty in finding a lawyer. So you have me. 2 It is an enormous pleasure to be asked to speak to you today and to do so in memory of Caroline Weatherill who died so tragically in 2006, shortly after giving birth to twin daughters. She was only a young woman and it was a life that was far too short. She had been admitted as an advocate in 1997 and during her articles had married Lawrence. She had quickly established herself as a very effective, well motivated and doughty advocate. She was a delightful funny and clever woman and had well-deservedly earned the respect of colleagues and clients alike. She will continue to be missed and mourned by her family and by a great many people who had good reason to be glad of and be grateful for her life. 3 Last year`s speaker was Lord Neuberger. Unfortunately I could not come but I note that he stayed at Government House and that there was a magnificent dinner for him there. -

GDC Inmate Handbook

NOTICE This handbook does not replace the official Rules and Regulations of the Georgia Department of Corrections. Information from the Rules and Regulations of the Department has been included to help you understand what is required of you, but this information is to be used in conjunction with the Rules and Regulations. In any case, where there is a conflict between information in the Rules and Regulations and information in this handbook, the Rules and Regulations are to be followed. 1 INTRODUCTION Treat your time in a Correctional Facility as an opportunity to correct mistakes, to learn how to return to society as a contributing member. While you are here, treat others as you would like to be treated, observe rules and regulations, and participate actively in available programs, and you will be closer to that goal. If you are entering a State Prison for the first time you will be interested in what is expected of you, as well as what will be provided to you, by the Georgia Department of Corrections. This booklet will answer some of your questions. It outlines the rules and regulations of the Department, as well as the disciplinary and grievance procedures that will apply to you during your incarceration. You will also learn about the programs offered through your institution. There are rules and regulations, which you will be expected to observe while in prison as you prepare for your release from prison. You will be treated humanely and you will be allowed to earn opportunities to change the life habits that helped put you in prison. -

TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-Wing *

116TH INTERNATIONAL TRAINING COURSE VISITING EXPERTS’ PAPERS TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-wing * I. INTRODUCTION This paper will draw heavily on the experience gained by law enforcement Triad societies are criminal bodies in the HKSAR in tackling the triad organisations and are unlawful under the problem. Emphasis will be placed on anti- Laws of Hong Kong. Triads have become a triad law and Police enforcement tactics. matter of concern not only in Hong Kong, Background knowledge on the structure, but also in other places where there is a beliefs and rituals practised by the triads sizable Chinese community. Triads are is important in order to gain an often described as organized secret understanding of the spread of triads and societies or Chinese Mafia, but these are how triads promote illegal activities by simplistic and inaccurate descriptions. resorting to triad myth. With this in mind Nowadays, triads can more accurately be the paper will examine the following issues: described as criminal gangs who resort to triad myth to promote illegal activities. • History and Development of Triads • Triad Hierarchy and Structure For more than one hundred years triad • Characteristics of Triads activities have been noted in the official law • Differences between Triads, Mafia and police reports of Hong Kong. We have and Yakuza a long history of special Ordinances and • Common Crimes Committed by related legislation to deal with the problem. Triads The first anti-triad legislation was enacted • Current Triad Situation in Hong in 1845. The Hong Kong Special Kong Administrative Region (HKSAR) has, by • Anti-triad Laws in Hong Kong far, the longest history, amongst other • Police Enforcement Strategy jurisdictions, in tackling the problem of • International Cooperation triads and is the only jurisdiction in the world where specific anti-triad law exists. -

Crime in Prisons: Where Now and Where Next?

Crime in prisons: Where now and where next? January 2019 John Campion Police and Crime Commissioner West Mercia Authors: Professor James Treadwell, Staffordshire University Dr Kate Gooch, School of Law, University of Leicester Georgina Barkham Perry, Department of Criminology, University of Leicester PCC regions covered are: Staffordshire, Warwickshire, West Mercia and West Midlands This report was commissioned by: John Campion Police and Crime Commissioner West Mercia 2 Crime in prisons: Where now and where next? Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Overview 5 3. Prisons in Context 6 4. Why Prison Crime in the Midlands Matters 8 5. Methodology 9 6. Defining Crime in Prison 11 7. The Scale and Nature of the Problem 12 The Illicit Economy 12 Drugs 13 Organised Crime Moving Inside 14 Criminal Finances in Prison 16 Short-term Imprisonment 17 Drugs in Prison 19 Illicit Mobile Phones 21 How can Mobile Phone Use be Countered? 22 Staff Corruption 25 8. Who is Involved 26 The Contemporary Prison Hierarchy 28 9. A Heterogenous Prison Estate 34 Young Offenders/Young Adults 34 The Women’s Prison Estate 34 Specialist Prisons for Men Convicted of Sex Offences 36 Category D (Open) Prisons 37 High Security (Dispersal) Prisons 37 10. Local Initiatives 39 11. Recommendations 45 National Policy 45 Local Initiatives and Local Recommendations 47 12. Conclusion 52 References 53 3 1 Introduction The vast majority of people in our country are law abiding The sense of determination and ‘joint endeavour’ was clear. and simply want to get on with their lives in a safe and However, what wasn’t clear was a sense that all agencies secure environment. -

Prisons (Interference with Wireless Telegraphy) Bill HL Bill 121 of 2017–19

Library Briefing Prisons (Interference with Wireless Telegraphy) Bill HL Bill 121 of 2017–19 Summary The Prisons (Interference with Wireless Telegraphy) Bill is a private member’s bill which would authorise public communication providers to disrupt the use of unlawful mobile phones in prisons. The provisions replicate those from the Government’s Prisons and Courts Bill (introduced in the 2016–17 session), which fell at the dissolution of Parliament for the 2017 general election.1 It would amend the Prisons (Interference with Wireless Telegraphy) Act 2012—which enabled prison governors to interfere with wireless telegraphy to disrupt mobile phone use in prisons—by allowing public communication providers to also interfere in an independent capacity. The bill was initially introduced in the House of Commons on 19 July 2017 by Ester McVey (Conservative MP for Tatton). However, when Ms McVey became a government minister in November 2017, Maria Caulfield (Conservative MP for Lewes) took over sponsorship of the bill. The bill received its second reading on 1 December 2017 and completed its stages with cross-party support in the Commons on 6 July 2018. On 9 July 2018, the bill received its first reading in the House of Lords under the sponsorship of Baroness Pidding (Conservative). It is due to receive its second reading in the Lords on 26 October 2018. Provisions of the Bill Clause 1 of the bill would amend section 1 of the Prisons (Interference with Wireless Telegraphy) Act 2012 (PIWTA) to allow the Secretary of State to authorise public communication providers (PCPs) to interfere with wireless telegraphy in prisons. -

Planning and Highways Commitee 28 June 2018 Item 12. Boddingtons

Manchester City Council Item 12 Planning and Highways Committee 28 June 2018 Application Number Date of Appln Committee Date Ward 118831/FO/2018 19th Jan 2018 31st May 2018 Cheetham Ward Proposal Erection of two buildings (a part 17, part 12 storey building and a part 26, part 23 storey building) to form 556 residential units (Use Class C3a) together with the creation of 3490 sqm of commercial floor space (Use Classes A1, A2, A3, B1 and D1) with associated landscaping, access and other associated works Location Former Boddingtons Brewery Site, Dutton Street, Manchester, M3 1LE Applicant Prosperity UX Manchester Developments Limited, C/o Agent, Agent Ms Melissa Wilson, Deloitte Real Estate, 2 Hardman Street, Spinningfields, Manchester, M3 3HF, Description The application site comprises the eastern section of the former Boddington Brewery site. This planning application forms part of the first phase of development of this site as part of realising the vision outlined within the Boddingtons Strategic Regeneration Framework which was first adopted by the City Council in 2007 and updated in 2015. The site measures approximately 1.376 hectares and is bounded by Dutton Street to the east, New Bridge Street to the south, Great Ducie Street beyond the surface car park to the west and a warehouse building between Charles Street and Dutton Street to the north. The former Boddington Brewery site closed in 2005 and the land which forms part of this planning application was cleared, together with the rest of the Boddington site, and the hardstanding that remained was turned into a 852 space surface car park. -

Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples

Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples September 2014 RACE in Europe Project Partners Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples “With the financial support of the Prevention of and Fight against Crime Programme European Commission- Directorate-General Home Affairs” ISBN 978–0–900918–91–0 Acknowledgements and contributors This publication was made possible by the information and advice provided by the RACE in Europe project partners and a variety of individuals, agencies and organisations across Europe, who have shared their experience, and agreed to be interviewed or to take part in focus groups. Our thanks go to all RACE in Europe seminar participants who provided information through interviews, questionnaires and group discussions. Anti-Slavery would like to thank in particular Vicky Brotherton, Fiona Waters, Marie Jelinkova, Grainne O’Toole, Viginija Petruskaite, Chloe Setter, Klara Skrivankova, Bernie Gravett, Michal Krebs and Walter Hilhorst for researching, writing and contributing their expertise and information for this publication. RACE in Europe project partner profiles UK Anti-Slavery International: Anti-Slavery International is the oldest human rights organisation in the world. The NGO works at the local, regional and international level to eliminate all forms of slavery around the world. www.antislavery.org ECPAT UK: ECPAT’s activities involve research, campaigning and lobbying government to prevent child exploitation and protect children in tourism and child victims of trafficking. www.ecpat.org.uk Specialist Policing Consultancy: Specialist Policing Consultancy provides expertise in combatting organised crime at an international level. -

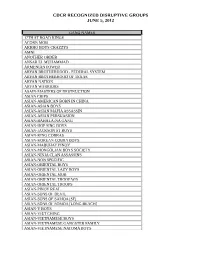

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

L'utilisation Des Sites De Réseautage

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. L’utilisation des sites de réseautage social à des fins criminelles : Étude et analyse du phénomène de « cyberbanging » Par Carlo Morselli, Ph. D. Université de Montréal et David Décary-Hétu Université de Montréal préparée pour la Division de la recherche et de la coordination nationale sur le crime organisé Secteur de la police et de l’application de la loi Sécurité publique Canada Les opinions exprimées n’engagent que les auteurs et ne sont pas nécessairement celles du ministère de la Sécurité publique. -

GMPR04 Bradford

Foreword B Contents B Bradford in East Manchester still exists as an electoral ward, yet its historical identity has waned Introduction 3 and its landscape has changed dramatically in The Natural Setting ...........................................7 recent times. The major regeneration projects that The Medieval Hall ...........................................10 created the Commonwealth Games sports complex Early Coal Mining ............................................13 and ancillary developments have transformed a The Ashton-under-Lyne Canal ........................ 17 former heavily industrialised area that had become Bradford Colliery ............................................. 19 run-down. Another transformation commenced Bradford Ironworks .........................................29 much further back in time, though, when nearly 150 The Textile Mills ..............................................35 years ago this area changed from a predominantly Life in Bradford ...............................................39 rural backwater to an industrial and residential hub The Planning Background ...............................42 of the booming city of Manchester, which in the fi rst Glossary ...........................................................44 half of the nineteenth century became the world’s Further Reading ..............................................45 leading manufacturing centre. By the 1870s, over Acknowledgements ..........................................46 15,000 people were living cheek-by-jowl with iconic symbols of the -

The Good Prison.Pdf

Gerard Lemos was described by Community Care magazine as ‘one of the UK’s leading thinkers on social policy’. His previous books include The End of the Chinese Dream: Why Chinese people fear the future published by Yale University Press and The Communities We Have Lost and Can Regain (with Michael Young). He has held many public appointments including as a Non-Executive Director of the Crown Prosecution Service. First published in 2014 Lemos&Crane 64 Highgate High Street, London N6 5HX www.lemosandcrane.co.uk All rights reserved. Copyright ©Lemos&Crane 2014 The right of Gerard Lemos to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-898001-75-1 Designed by Tom Keates/Mick Keates Design Printed by Parish Print Consultants Limited To navigate this PDF, click on the chapter headings below, you can return to the table of contents by clicking the return icon Contents Foreword vii Introduction 8 Part One : Crime and Society 15 1. Conscience, family and community 15 2. Failure of conscience in childhood and early family experiences of offenders 26 3. The search for punishment 45 4. A transformed social consensus on crime and punishment since the 1970s 56 5. Justice and restoration 78 Part Two: The Good Prison 92 6. Managing the Good Prison 92 7. Family life of prisoners and opportunities for empathy 110 8. Mindfulness: reflection and collaboration 132 9. Creativity and artistic activity 159 10.