Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

50 bus time schedule & line map 50 Media City - East Didsbury View In Website Mode The 50 bus line (Media City - East Didsbury) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) East Didsbury: 12:10 AM - 11:40 PM (2) Manchester City Centre: 12:09 AM - 11:39 PM (3) The Lowry: 5:05 AM - 11:09 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 50 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 50 bus arriving. Direction: East Didsbury 50 bus Time Schedule 49 stops East Didsbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:10 AM - 11:44 PM Monday 4:55 AM - 11:40 PM The Quays/Mediacityuk (At) Tuesday 12:10 AM - 11:40 PM Harbour City Metrolink Stop, Salford Quays Wednesday 12:10 AM - 11:40 PM Chandlers Point, Salford Quays Thursday 12:10 AM - 11:40 PM Paragon House, Broadway Friday 12:10 AM - 11:40 PM Broadway, Salford Saturday 12:10 AM - 11:40 PM Dakota Avenue, Langworthy Montford Street, Langworthy South Langworthy Road, Salford 50 bus Info South Langworthy Road, Langworthy Direction: East Didsbury Carolina Way, Salford Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 59 min Langworthy Road, Langworthy Line Summary: The Quays/Mediacityuk (At), Langworthy Road, Salford Harbour City Metrolink Stop, Salford Quays, Chandlers Point, Salford Quays, Paragon House, Langworthy Road, Pendleton Broadway, Dakota Avenue, Langworthy, Montford Street, Langworthy, South Langworthy Road, Wall Street, Pendleton Langworthy, Langworthy Road, Langworthy, Fitzwarren Street, Salford Langworthy Road, Pendleton, Wall Street, Pendleton, Salford Shopping Centre, Pendleton, Pendleton -

For Public Transport Information Phone 0161 244 1000

From 27 October Bus 10 Evening journeys are extended to serve Brookhouse 10 Easy access on all buses Brookhouse Peel Green Patricroft Eccles Liverpool Street Pendleton Lower Broughton Manchester From 27 October 2019 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Arriva North West PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 19-SC-0403–G10– 4000–0919 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Arriva North West large print, Braille or recorded information 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Liverpool, L9 5AE Telephone 0344 800 4411 Easy access on buses Journeys run with low floor buses have no Travelshops steps at the entrance, making getting on Eccles Church Street and off easier. Where shown, low floor Mon to Fri 7.30am to 4pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Sat 8am to 11.45am and 12.30pm to 3.30pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Sunday* Closed bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Manchester Piccadilly Gardens easy access services where these services are Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm scheduled to run. Sunday 10am to 6pm Public hols 10am to 5.30pm Using this timetable Manchester Shudehill Interchange Timetables show the direction of travel, bus Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm numbers and the days of the week. Sunday Closed Main stops on the route are listed on the left. -

For Public Transport Information Phone 0161 244 1000

From 21 July to 31 August Bus Summer Times 50 Monday to Friday times are changed during the Summer period 50 Easy access on all buses East Didsbury Burnage Kingsway Victoria Park Manchester University of Salford Pendleton Salford Shopping Centre Salford Quays MediaCityUK From 21 July to 31 August 2019 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Stagecoach PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 19-SC-0067-G50-web-0619 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Stagecoach large print, Braille or recorded information Head Office, Hyde Road, Ardwick phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Manchester, M12 6JS Telephone 0161 273 3377 Easy access on buses Journeys run with low floor buses have no Travelshops steps at the entrance, making getting on Manchester Piccadilly Gardens and off easier. Where shown, low floor Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Sunday 10am to 6pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Public hols 10am to 5.30pm bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Manchester Shudehill Interchange easy access services where these services are Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm scheduled to run. Sunday Closed Public holidays 10am to 1.45pm Using this timetable and 2.30pm to 5.30pm Timetables show the direction of travel, bus numbers and the days of the week. -

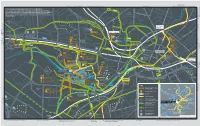

Getting to Salford Quays Map V15 December 2015

Trams to Bury, Ú Ú Ú Ú Ú Ú Bolton Trains to Wigan Trains to Bolton and Preston Prestwich Oldham and Rochdale Rochdale Rochdale to Trains B U R © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 0100022610. B Y R T Use of this data is subject to terms and conditions: You are granted a non-exclusive, royalty O NCN6 E A LL E D E and Leeds free, revocable licence solely to view the Licensed Data for non-commercial purposes for the R W D M T S O D N A period during which Transport for Greater Manchester makes it available; you are not permitted R S T R Lower E O R C BRO to copy, sub-license, distribute, sell or otherwise make available the Licensed Data to third E D UG W R E A HT T O Broughton ON S R LA parties in any form; and third party rights to enforce the terms of this licence shall be reserved NE E L to Ordnance Survey W L L R I O A O H D L N R A D C C D Ú N A A K O O IC M S T R R T A T H E EC G D A H E U E CL ROAD ES LD O R E T R O R F E B R Ellesmere BR E O G A H R D C Park O D G A Pendleton A O R E D R S River A Ú T Ir Oldham Buile Hill Park R wel T E W E l E D L D T Manchester A OL E U NE LES A D LA ECC C H E S I Victoria G T T E C ED Salford O E Peel Park E B S R F L E L L R A T A S A Shopping H T C S T K N F O R G Centre K I T A D W IL R Victoria A NCN55 T Salford Crescent S S O O R J2 Y M R A M602 to M60/M61/M62/M6 bus connections to bus connections to Ú I W L Salford Royal T L L L R E Salford Quays (for MediaCityUK) H Salford Quays (for MediaCityUK) R A A O Hospital T S M Seedley Y A N N T A E D T H E A E E D S L L R -

Greater Manchester Transport Committee

Public Document Greater Manchester Transport Committee DATE: Friday, 17 January 2020 TIME: 10.30 am VENUE: Friends Meeting House, Mount Street, Manchester Nearest Metrolink Stop: St Peters Square Wi-Fi Network: Public Agenda Item Pages 1. APOLOGIES 2. CHAIRS ANNOUNCEMENTS AND URGENT BUSINESS 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 1 - 4 To receive declarations of interest in any item for discussion at the meeting. A blank form for declaring interests has been circulated with the agenda; please ensure that this is returned to the Governance & Scrutiny Officer at the start of the meeting. 4. MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD 8 NOVEMBER 2019 5 - 14 To consider the approval of the minute of the meetings held on 8 November 2019. Please note that this meeting will be livestreamed via www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk, please speak to a Governance Officer before the meeting should you not wish to consent to being included in this recording. 5. GM TRANSPORT COMMITTEE WORK PROGRAMME 15 - 20 Report of Liz Treacy, GMCA Monitoring Officer. 6. TRANSPORT NETWORK PERFORMANCE 21 - 32 Report of Bob Morris, Chief Operating Officer, TfGM. 7. RAIL PERFORMANCE REPORT 33 - 64 Report of Bob Morris, Chief Operating Officer, TfGM. BUS OPERATIONAL ITEMS 8. BUS PERFORMANCE REPORT 65 - 80 Report of Alison Chew, Interim Head of Bus Services, TfGM. 9. FORTHCOMING CHANGES TO THE BUS NETWORK 81 - 120 Report of Alison Chew, Interim Head of Bus Services, TfGM. STRATEGIC ITEMS 10. TRANSPORT AND CLIMATE CHANGE 121 - 134 Report of Simon Warburton, Transport Strategy Director, TfGM. 11. STREETS FOR ALL AND MADE TO MOVE PROGRESS UPDATE 135 - 148 Report of Simon Warburton, Transport Strategy Director, TfGM and Chris Boardman, GM Cycling and Walking Commissioner. -

GMPR04 Bradford

Foreword B Contents B Bradford in East Manchester still exists as an electoral ward, yet its historical identity has waned Introduction 3 and its landscape has changed dramatically in The Natural Setting ...........................................7 recent times. The major regeneration projects that The Medieval Hall ...........................................10 created the Commonwealth Games sports complex Early Coal Mining ............................................13 and ancillary developments have transformed a The Ashton-under-Lyne Canal ........................ 17 former heavily industrialised area that had become Bradford Colliery ............................................. 19 run-down. Another transformation commenced Bradford Ironworks .........................................29 much further back in time, though, when nearly 150 The Textile Mills ..............................................35 years ago this area changed from a predominantly Life in Bradford ...............................................39 rural backwater to an industrial and residential hub The Planning Background ...............................42 of the booming city of Manchester, which in the fi rst Glossary ...........................................................44 half of the nineteenth century became the world’s Further Reading ..............................................45 leading manufacturing centre. By the 1870s, over Acknowledgements ..........................................46 15,000 people were living cheek-by-jowl with iconic symbols of the -

Messages Report Nov 1 Copy.Pptx

FACEBOOK Blah blah Messages etc.. ENGAGEMENT ANALYSIS CHARTS The chart in this document is collated daily by us as part of our commitment to ensure the marketing we conduct at our schemes is as social as it is effective for both the centres and their tenants. The statistics represent independent figures provided by Facebook and is based on the algorithms they run evaluating the relative performance of Pages and Posts relative to ‘Engagement’, measuring reactions, comments and shares. Messages PR harvest figures for 240 UK Shopping Centres and present them in a tabular form. We display the results in relative terms, which allows us to judge the performance of Pages when comparing the size of schemes and the number of ‘Page likes’ they enjoy. We also show the absolute positions where more Page likes, bigger budgets and boosts all work to generate increased engagement. Messages PR deliver astonishing results, regardless of how they are measured. In this vital Christmas sales period, our centres were placed within 10 of the top 20 places in relative terms and occupied the entire top 7. Even in absolute terms we placed 4 schemes in the top 10 UK Centre pages. Pentagon, Chatham was also number one in absolute terms, the best performing UK Shopping Scheme on Facebook, outperforming the mega centre Bluewater. Similarly Parkway in Middlesbrough outperformed The Metro Centre and Grays outperformed intu Lakeside by significant margins as you can see from the charts. We do not achieve these results by clever tweaking of posts, giveaways or boosts – It is because the work we undertake is genuinely social that we generate extraordinary results on social media. -

Quays Culture Information: June-July 2017

QUAYS CULTURE INFORMATION: JUNE-JULY 2017 HOME Welcome to Quays Culture, the home of inspiring digital, interactive art at MediaCityUK, Salford Quays. Here you can find out about our exciting, free participatory art projects that bring together local communities, artists pushing the boundaries of what digital art can achieve, and an illustrious group of organisations that call Salford Quays home. PROGRAMME Quays Culture is the artistic team behind the large-scale art events at Salford Quays and MediaCityUK. Our artistic programme immerses audiences into new and exciting public- realm exhibitions that are inspired by its surroundings, with a focus on technology, creativity and digital innovation. Working with local talent as well as internationally renowned artists, Quays Culture’s work ranges from the intimate to the monumental, inspiring audiences to engage with the location in new and exciting ways. TEAM Meet the team behind Quays Culture. We’re all passionate about bringing world-class artistic experiences to The Quays, combining cutting-edge technology with creative thinking! Lucy DusgAte: Programme Producer As the Creative Producer and lead on the Quays Culture artistic programme Lucy develops and implements the artistic vision that puts technology and digital practice at the forefront of our events. This involves large-scale commissioning of new artworks and presentations of existing artworks by artists from across the globe, making Quays Culture a significant contributor to the development of contemporary digital art in the UK. She draws on her extensive experience from throughout her career, with previous roles focussing on technology, imagery, digital and creativity. These include; Digital Manager for Arts Council England, Artistic Director of Lumen Arts, Deputy Director of Lumen Arts Ltd, General Manager positions for Picturehouse Cinemas, Theatre Manager of Royal Court Theatre and Cinemas Manager at the ICA in London, as well as work as a freelance commercial photographer. -

Downloading a List Here

Book Shop Name Book Shop Name 2 Address Address 2 Town County Post Code Country A Bundle of Books 6 Bank Street Herne Bay Kent CT6 5EY Aardvark Books Ltd The Bookery Manor Farm Brampton Bryan Shropshire SY7 0DH Aberconwy House National Trust Enterprise National Trust Shop Castle Street Conwy Gwynedd LL32 8AY Wales Alisons Bookshop 138/139 High Street Tewkesbury Gloucestershire GL20 5JR Allan Bank Retail National Trust Enterprise Allan Bank Grasmere Cumbria LA22 9QB Allbooks + News Allbooks Limited Lyster Square Portlaoise County Laois Ireland Antonia's Bookstore Navangate Trim County Meath Ireland Archway Bookshop Church Street Axminster Devon EX13 5AQ Argyll Book Centre Clan of Callander Ltd Lorne Street Lochgilphead Argyll and Bute PA31 8LU Scotland Asda Abedare Riverside Retail Park Aberdare Rhondda Cynon Taff CF44 0AH Wales Asda Aberdeen Beach Boulevard Retail Park Beach Boulevard Aberdeen AB24 5EZ Scotland Asda Bridge of Dee Garthdee Road Aberdeen AB10 7QA Scotland Asda Dyce Riverview Drive Dyce Aberdeen AB21 7NG Scotland Asda Accrington Hyndburn Road Accrington Lancashire BB5 1QR Asda Alloa Whins Road Alloa Clackmannanshire FK10 3SD Scotland Asda Living Altringham Altrincham Retail Park George Richards Way Broad Heath Greater Manchester WA14 5GR Asda Andover Anton Mill Road Andover Hampshire SP10 2RW Asda Antrim 150 Junction One Internmational Outlet Antrim County Antrim BT41 4LL Northern Ireland Asda Arbroath Westway Retail Park Arbroath Angus DD11 2NQ Scotland Asda Ardrossan Harbour Street Ardrossan North Ayrshire KA22 8AZ Scotland -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Police-Led Boys’ Clubs in England and Wales, 1918-1951 Thesis How to cite: Wilburn, Elizabeth (2020). Police-Led Boys’ Clubs in England and Wales, 1918-1951. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.00010dc9 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Name: Elizabeth Alice Wilburn Title: Police-led boys’ clubs in England and Wales, 1918-1951 Degree: History Discipline: Policing and Criminal Justice Date: January 2019 1 2 Abstract Police-led boys’ clubs were established across England and Wales, in industrial towns and cities, during the interwar and immediate post-war period. They were founded and organised by Chief Constables, and high-ranking police officers. Their activities were reported upon in local, regional and national newspapers. Club organisers aimed to harness the ‘high spirits’ of boys in a positive way, removing them from the streets and the temptations of juvenile delinquency. They were run on a daily basis by working-class Police Constables, who were motivated for a variety of reasons to volunteer in them during their free time. -

Private Hire Driver & Hackney Carriage

Private Hire Driver & Hackney Carriage Knowledge Test Revision Guide Version 1.2 (updated 06 January 2016) © Manchester City Council. You may NOT reproduce this document in its entirety.manchester.gov.uk Any partial reproduction or alteration is expressly forbidden without the prior permission of the copyright holder. 2 Private Hire Driver & Hackney Carriage Knowledge Test: Revision Guide Private Hire Driver & Hackney Carriage Knowledge Test: Revision Guide 3 Contents Introduction ........................................4 Conditions and Customer Care ........... 27 The Knowledge Test what you need Lists, locations, to pass .................................................5 places and premises ....................... 28 Section 1 City Centre bars, restaurants and Private Hire and Hackney Carriage ....6 private clubs ......................................28 Part 1: Reading and understanding the Hotels ............................................... 32 Greater Manchester A–Z Atlas .............6 Transport interchanges ......................34 Finding a location in the A–Z Hospitals ........................................... 35 Finding ‘St’, ‘Sa’ and ‘Gt’ locations .......... 7 City Centre banks, building societies ..36 Part 2: Places Theatres, libraries and cinemas ..........36 Finding ‘The’ locations..............................8 Exhibition centres, conference Section 2 centres, art galleries and museums .... 37 Private Hire .....................................9 Parks and open spaces ....................... 37 Part 1: Routes from one -

The Plan for Atherton

THE PLAN VOLUME 4 | ATHERTON CONTENTS AT 1. INTRODUCTION HERTON 2. ATHERTON TODAY 3. OUR VISION 4. DELIVERY FOREWORD With its great schools, high quality network. greenspace, attractive heritage buildings and excellent road and rail We know that a high quality, diverse transport connections, Atherton has housing offer is key to supporting much to be proud of. town centres. Atherton already has several developments underway and Atherton’s centre continues to more are planned, including up to thrive as a bustling local town with a 2,000 new homes to the south and diverse mix of unique independent east of the town centre. We must shops and leisure venues and ensure that we create sustainable a developing quality night-time urban neighbourhoods through new economy with an increasing number housing development, providing not of busy restaurants, cafes and only high-quality homes but also the bars. Atherton’s location close to opportunity to live, work and play in a Manchester also offers great potential desirable setting. for future growth. Atherton is one of the best-connected This Plan is the first step in helping towns in the north west, with road to achieve that growth, highlighting links to the M61, M60 and M6 what we already have in the town motorways and with a choice of and surrounding area, and what we two railway stations. More recently, can build on for the future. Atherton has also benefitted from the Leigh – Salford – Manchester A considerable opportunity is the Guided Busway and there are further huge amount of development in opportunities to improve transport and around the town.