Learning the Languages of Nostalgia in Modern and Contemporary Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Young Galeano Writing About New China During the Sino-Soviet Split

Doubts and Puzzles: Young Galeano Writing about New China during the Sino-Soviet Split _____________________________________________ WEI TENG SOUTH CHINA NORMAL UNIVERSITY Abstract As a journalist of Uruguay’s Marcha weekly newspaper, Eduardo Galeano visited China in September 1963; he was warmly received by Chinese leaders including Premier Zhou Enlai. At first, Galeano published some experiences of his China visit in Marcha. In 1964, he published the complete journal of the trip, under the title of China, 1964: crónica de un desafío [“China 1964: Chronicle of a Challenge”]. Based on Chinese-language materials, this paper explores Galeano’s trip to China at that time and includes a close reading of Galeano’s travel notes. By analyzing his views on the New China, Socialism, and the Sino-Soviet Split, we will try to determine whether this China visit influenced his world view and cultural concepts. Keywords: Galeano, The New China, Sino-Soviet Split Resumen Como periodista del semanario uruguayo Marcha, Eduardo Galeano visitó China en septiembre de 1963 donde fue calurosamente recibido por los líderes chinos, incluido el Primer Ministro Zhou Enlai. Al principio, Galeano publicó algunas experiencias de su visita a China en Marcha. En 1964, publicó el diario completo del viaje bajo el título China, 1964: crónica de un desafío. Basado en materiales en chino, este artículo explora el viaje de Galeano e incluye una lectura detallada de sus notas. Por medio de un análisis de sus puntos de vista sobre la Nueva China, el socialismo y la ruptura sinosoviética, se intenta determinar si esta visita a China influyó en su visión del mundo y en sus conceptos culturales. -

A Don West Reader West End Press

Lincoln Memorial University LMU Digital Commons Copyright-Free Books Collection Special Collections 1985 In a Land of Plenty: A Don West Reader West End Press Don West Constance Adams West Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmunet.edu/csbc Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation End Press, West; West, Don; and West, Constance Adams, "In a Land of Plenty: A Don West Reader" (1985). Copyright-Free Books Collection. 1. https://digitalcommons.lmunet.edu/csbc/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at LMU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Copyright-Free Books Collection by an authorized administrator of LMU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. With sketches Constance Adams West No Grants This book is not supported any grant, governmental, corporate or PS 3545 .E8279 16 1985 private. It is paid for, directly or indirectly, by the people who support and In a land of plenty have Don West's vision, and it both reflects and proves their best - The publisher No Purposely this book is not copyrighted. Poetry and other creative efforts should be levers, weapons to be used in the people's struggle for understanding, human rights, and decency. "Art for Art's Sake" is a misnomer. The poet can never be neutral. In a hungry world the struggle between oppressor and oppressed is unending. There is the inevitable question: "Which side are you on?" To be content with as they are, to be "neutral," is to take sides with the oppressor who also wants to keep the status quo. -

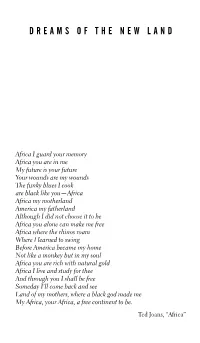

Dreams of the New Land

When History Sleeps: A Beginning 13 DREAMS OF THE NEW LAND Africa I guard your memory Africa you are in me My future is your future Your wounds are my wounds The funky blues I cook are black like you—Africa Africa my motherland America my fatherland Although I did not choose it to be Africa you alone can make me free Africa where the rhinos roam Where I learned to swing Before America became my home Not like a monkey but in my soul Africa you are rich with natural gold Africa I live and study for thee And through you I shall be free Someday I’ll come back and see Land of my mothers, where a black god made me My Africa, your Africa, a free continent to be. Ted Joans, “Africa” 14 Freedom Dreams Schoolhouse Rock didn’t teach me a damn thing about “free- dom.” The kids like me growing up in Harlem during the 1960s and early 1970s heard that word in the streets; it rang in our ears with the regularity of a hit song. Everybody and their mama spoke of freedom, and what they meant usually defied the popular meanings of the day. Whereas most Americans associated free- dom with Western democracies at war against communism, free- market capitalism, or U.S. intervention in countries such as Viet- nam or the Dominican Republic, in our neighborhood “freedom” had no particular tie to U.S. nationality (with the pos- sible exception of the black-owned Freedom National Bank). Freedom was the goal our people were trying to achieve; free was a verb, an act, a wish, a militant demand. -

Reconfiguring Untidiness: the Ethics of Remembering History

RECONFIGURING UNTIDINESS: THE ETHICS OF REMEMBERING HISTORY IN NOVELS BY VIRGINIA WOOLF, D. M. THOMAS, AND IAN MCEWAN A Dissertation by SEUNG-HYUN KIM Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Mary Ann O’Farrell Committee Members, Marian Eide David McWhirter Theodore George Head of Department, Maura Ives August 2019 English Copyright 2019 Seung-Hyun Kim ABSTRACT This dissertation examines representations of ideas about untidiness in modern and contemporary British novels. Reading works by Virginia Woolf, D. M. Thomas, and Ian McEwan as memory texts that engage historical atrocities, I investigate the ways in which the attention to small-scale violence of the everyday as manifested in the novels’ conceptualizations of the untidy is entwined with their articulation of violence perpetrated on a massive scale, the wars and the Holocaust. As both a thematic and a formal concern, the trope of the untidy illuminates paradigms established on exclusion, acts of boundary-setting that obliterate the face of the Other even as it puts into play literary elements that dispel such brutalizing operations. I make the case that the reconfiguration of untidiness as a form of relinquishing the self’s autonomy to relate to the Other is integral to how the novels explore the ethics of remembering history. This dissertation rethinks Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway as a historical novel that intervenes in the author’s contemporary discourse about remembering the recent past of the Great War. Disrupting dominant culture’s homogenizing affective economy, the novel’s thematization of untidiness through two women’s love figures a nonappropriative mode of relating to the Other that transfers onto the novel’s metacritical ruminations upon engaging a violent past in ways that preserve the unassimilability of the subject matter. -

GUIMARÃES ROSA E GRACILIANO RAMOS Hermenegildo

UM ANTAGONISMO FECUNDO: GUIMARÃES ROSA E GRACILIANO RAMOS A FECUND ANTAGONISM: GUIMARÃES ROSA E GRACILIANO RAMOS Hermenegildo Bastos* RESUMO: Projeto de análise das diferenças antagônicas entre Gui- marães Rosa e Graciliano Ramos como sinal de fecundidade da moderna ficção brasileira. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Moderna ficção brasileira, Guimarães Rosa, Graciliano Ramos. ABSTRACT: Project of analysis of the antagonistic difference be- tween Guimarães Rosa and Graciliano Ramos as sign of fecundity of the modern brasilian fiction. KEY WORDS: Modern Brasilian fiction, Guimarães Rosa, Gra- ciliano Ramos. * Professor Doutor da Universidade de Brasília. Email: [email protected]. UM ANTAGONISMO FECUNDO: GUIMARÃES ROSA E GRACILIANO RAMOS Procuro analisar obras de dois ficcionistas brasileiros modernos (Guima- rães Rosa e Graciliano Ramos), e explorar um possível e fecundo contra- ponto entre os dois. Ao mesmo tempo, a partir dos estudos sobre os escrito- res, pretendo discutir os modelos historiográficos com que tem trabalhado a crítica nas análises da passagem do regionalismo crítico ao super-regio- nalismo. Trata-se, portanto, de uma investigação sobre literatura brasileira e, ao mesmo tempo, sobre modelos de crítica e história da literatura, espe- cificamente sobre a evolução do regionalismo. Assim, este texto que agora apresento é parte de uma pesquisa maior em andamento. As duas dimensões da pesquisa são indissociáveis: por um lado os mo- delos historiográficos parecem ter se congelado e, com isso, parecem ter perdido a capacidade de iluminar as leituras dos escritores; por outro lado, as leituras e as análises, que já se formulam, ainda que não se dêem conta disto, a partir do modelo dominante, correm o risco de repetir visões este- reotipadas. -

Graciliano Ramos: O Escritor E O Homem

Revista Graduando nº1 jul./dez. 2010 GRACILIANO RAMOS: O ESCRITOR E O HOMEM Eliseu Ferreira da Silva G r a d u a n d o do curso de Letras Vernáculas (UEFS ) [email protected]; [email protected] Resumo : A literatura regionalista ou modernismo de 30 teve seu auge com o advento do romance nordestino, caracterizando -se por adotar uma visão crítica das relações sociais, voltada para os problemas do trabalhador rural, a seca e a miséria, ressal- tando o homem hostilizado pelo ambiente, pela terra, pela cida- de, o homem consumido pelos problemas impostos pelo meio. Um dos autores revelados nessa época, exímio observador psicológico do homem, bem como da sociedade, foi Graciliano Ramos que, mesmo sendo tratado por muitos críticos como um escritor amargo, rude, demonstra o contrário, compaixão, amor, amizade ao narrar os causos de Alexandre com muito bom - humor. Palavras - Chave: Graciliano Ramos- Alexandre e outros heróis - Causos- Solidão-Fan tasia Abstr act : Regionalist Literature or 1930´s Modernism reached its apogee with the introduction of the Northeastern Novel, adopt- ing a critical view of social relationships, addressing to the problems of peasants, draught, misery and their struggle against adversities of the environment, of living in the country and of living in the city. One of the authors emerging from that literary movement, an acute observer of man´s psyche as well as of society, Graciliano Ramos, although taken by some critics as a bitter rude Writer, when narrating the stories of Alexandre in such a light mood, demonstrates the opposite: compassion, love, friendship. Keywords: Graciliano Ramos- Alexandre and others heroes - stories- Solitude-Fantasy J 139 ISSN 2236-3335 Revista Graduando nº1 jul./dez. -

Novos Ramos De Graciliano – Três Inéditos Do Autor De Vidas Secas

Novos Ramos de Graciliano – três inéditos do autor de Vidas secas [ New Branches of Graciliano – Three unpublished texts by the author of “Vidas secas” Thiago Mio Salla1 SALLA, Thiago Mio. Novos Ramos de Graciliano – três inéditos do autor de Vidas secas. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, Brasil, n. 66, p. 251-270, abr. 2017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-901X.v0i66p251-270 1 Universidade de São Paulo (USP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil). Na obra memorialística Graciliano: retrato fragmentado, Ricardo Ramos se revelava um tanto quanto surpreso ao diagnosticar que, por mais que a obra de seu pai tivesse sido alvo até então de pesquisas febris, as quais, ao longo dos anos, desenterraram “crônicas, poesias, toda a obra juvenil e imatura de Graciliano, alcançando pseudônimos [...] secretos”2, ninguém houvesse conferido atenção aos textos do autor de Vidas secas estampados em periódicos comunistas ou que estavam na órbita de influência do PCB. Quase a totalidade dessa produção, até há pouco tempo inédita em livro, ganhou espaço na obra Garranchos (2012). Todavia, na recolha do material que compôs tal volume, alguns textos ficaram pelo caminho e, agora, puderam ser, enfim, recuperados, tendo em vista a ampliação das pesquisas feitas inicialmente. Trata-se das crônicas “O melhor dos mundos” e “Coisas da China”, além do telegrama “O atentado contra o escritor Wladimir Guimarães”, publicados em diferentes veículos de orientação esquerdista entre 1945 e 1951, isto é, na porção final da vida do romancista alagoano3. O melhor dos mundos Considerando-se tais aspectos, inicia-se esta pequena seleta de textos inéditos em livro de Graciliano com o escrito “O melhor dos mundos”, produção que, em 15 de agosto de 1945, ganhou as páginas do jornal A Manha, dirigido pelo Barão de Itararé (Aparício Torelly). -

Monteiro Lobato, Graciliano Ramos, João Guimarães Rosa

MONTEIRO LOBATO, GRACILIANO RAMOS, JOÃO GUIMARÃES ROSA E RADUAN NASSAR: UM OLHAR ATRAVÉS DO SÉCULO XX Maidi Migliorança 1 1 Maidi Migliorança , professora, graduação pela Faculdade de Filosofia Ciência e Letras de Umuarama – Paraná, concluída em 1982; Especialização em Literatura Brasileira pela UNIOESTE, no período de 02/1993 a 12/1994 – Campus de Marechal Cândido. Rondon – Paraná. Dois padrões de Língua Portuguesa fixados no Col. Est. Mal. Gaspar Dutra _EFM, em Nova Santa Rosa, Paraná. RESUMO O presente artigo é o resultante do estudo sobre os contos “Bucólica” e “Urupês”, (dois dos quinze contos que compõem a obra Urupês, de Monteiro Lobato); pelo romance Vidas secas, de Graciliano Ramos; pelo conto “Sarapalha”, que integra o livro Sagarana, pelo conto “Desenredo”, conto de Tutaméia (Terceiras estórias), ambos de Guimarães Rosa, e pelo romance Lavoura arcaica, de Raduan Nassar. Optou-se por essas obras por serem as mesmas relevantes para a Literatura Brasileira do século XX. O texto se ateve, ainda, à recepção das mesmas pelos estudantes e à preocupação dos professores de literatura em como suscitar nos alunos o desejo de ler e, a partir da leitura, contribuir para uma provável fruição das obras literárias. A prática da leitura no ambiente escolar pode – contrariamente ao que se objetiva – se constituir em fator de aversão à literatura, visto que o estudante tende a percebê-la como algo imposto, monitorado e subordinado a regras, a hierarquia, a avaliações. A construção do ser humano erige-se com pouco prazer e muita dor, por isso, travessia que o leitor empreenderá pelas pode ser dolorosa frente à complexidade das mesmas; podem constituir-se, a princípio, em dor, mas se adequadamente conduzidas, em posterior fruição. -

Finding the Exit: Ideology and Aperture in Graciliano Ramos

Finding the Exit: Ideology and Aperture in Graciliano Ramos Holly Jackson University of California at Berkeley Abstract: What ideological structures produce the linguistically austere worlds of Graciliano Ramos’s novels? What are the effects of reading outside of these seemingly all-consuming structures? These questions motivate this article’s discussion of two novels: São Bernardo and Vidas secas. In recuperating the complexity of expression in Graciliano’s writing, the article explores distinct modes of language as resistance to stereotypes about Brazilian Northeasterners—stereotypes that are often reproduced in literary criticism. The article considers this resistance both within language, in misuse (circularity, lying, [mis]appropriation, the breakdown of narrative time), and to language, in the textual presence of silence. Keywords: São Bernardo, Vidas secas, Brazilian Regionalism, silence, narrative time The theme of futility is a current in much of the critical work on Graciliano Ramos’s writing. Graciliano’s works are “uma sátira violenta e um panfleto furioso contra a humanidade” (Lins 132); “uma série de experiências de humi- lhação, de degradação, físicas, morais ou psicológicas” (Casais Monteiro 166); “[um] sistema literário pessimista” where all humans “obedecem a uma fata- lidade cega e má … que os leva a caminhos pré-traçados” (Candido, “Ficção” 53). Although characters may attempt to transform their surroundings, “sabem que todo é inútil” (Sarmento Lima 15). Obedience to broad power structures that predetermine subjectivities subsumes individual realities: the inhabit- 13 (2015): 121-144 | © 2015 by the American Portuguese Studies Association Studies Portuguese the American 13 (2015): 121-144 | © 2015 by ants of these worlds “rodam num âmbito exíguo, sem saída nem variedade” (Candido, “Os bichos” 87). -

New Cultural Models in Women-S Fantasy Literature Sarah Jane Gamble Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University

NEW CULTURAL MODELS IN WOMEN-S FANTASY LITERATURE SARAH JANE GAMBLE SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD, DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE OCTOBER 1991 NEW CULTURAL MODELS IN WOMEN'S FANTASY LITERATURE Sarah Jane Gamble This thesis examines the way in which modern women writers use non realistic literary forms in order to create new role models of and for women. The work of six authors are analysed in detail - Angela Carter, Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, Ursula Le Guin, Joanna Russ and Kate Wilhelm. I argue that they share a discontent with the conventions of classic realism, which they all regard as perpetuating ideologically-generated stereotypes of women. Accordingly, they move away from mimetic modes in order to formulate a discourse which will challenge conventional representations of the 'feminine', arriving at a new conception of the female subject. I argue that although these writers represent a range of feminist responses to the dominant order, they all arrive at a s1mil~r conviction that such an order is male-dominated. All exhibit an awareness of the work of feminist critics, creating texts which consciously interact with feminist theory. I then discuss how these authors use their art to examine the their own situation as women who write. All draw the attention to the existence of a tradition of female censorship, whereby the creative woman has experienced, in an intensified form, the repreSSion experienced by all women in a culture which privileges the male over the female. All these writers exhibit a desire to escape such a tradition, progressing towards the formulation of a utopian female subject who is free to be fully creative a project they represent metaphorically in the form of a quest.