Reconfiguring Untidiness: the Ethics of Remembering History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Learning the Languages of Nostalgia in Modern and Contemporary Literature

Learning the Languages of Nostalgia in Modern and Contemporary Literature Tasha Marie Buttler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Carolyn Allen, Chair Katherine Cummings Mark Patterson Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract Learning the Languages of Nostalgia in Modern and Contemporary Literature Tasha M. Buttler Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Carolyn Allen Department of English This dissertation builds upon recent discourses on nostalgia that focus on the generative potential of a sustained melancholic stance and position the past as resource for the future. My particular interest is in the potential for de-subjectification out of regulatory regimes, as outlined in the work of Judith Butler, particularly in The Psychic Life of Power. This text has allowed me to develop a robust theory about accumulated experiences of love and loss that are central to the formation of “character” that repeats or disrupts patterns of social relation. I differentiate between politicized nostalgia and experiential nostalgia, suggesting that the latter can make use of inevitable experiences of loss by initiating and sustaining a melancholic agency. I use various literary texts and memoirs to identify how the thwarting of melancholia can lead to nostalgia’s obverse: the desire to return suffering, or what Czech author Milan Kundera calls litost. These instances of thwarted grieving are positioned against a set of characters in the work of Virginia Woolf, Eva Hoffman, and Clarice Lispector who allow themselves to honor their experiential nostalgia rather than reverting to politicized nostalgia that repeats representations and clichés associated with empire. -

A Don West Reader West End Press

Lincoln Memorial University LMU Digital Commons Copyright-Free Books Collection Special Collections 1985 In a Land of Plenty: A Don West Reader West End Press Don West Constance Adams West Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmunet.edu/csbc Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation End Press, West; West, Don; and West, Constance Adams, "In a Land of Plenty: A Don West Reader" (1985). Copyright-Free Books Collection. 1. https://digitalcommons.lmunet.edu/csbc/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at LMU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Copyright-Free Books Collection by an authorized administrator of LMU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. With sketches Constance Adams West No Grants This book is not supported any grant, governmental, corporate or PS 3545 .E8279 16 1985 private. It is paid for, directly or indirectly, by the people who support and In a land of plenty have Don West's vision, and it both reflects and proves their best - The publisher No Purposely this book is not copyrighted. Poetry and other creative efforts should be levers, weapons to be used in the people's struggle for understanding, human rights, and decency. "Art for Art's Sake" is a misnomer. The poet can never be neutral. In a hungry world the struggle between oppressor and oppressed is unending. There is the inevitable question: "Which side are you on?" To be content with as they are, to be "neutral," is to take sides with the oppressor who also wants to keep the status quo. -

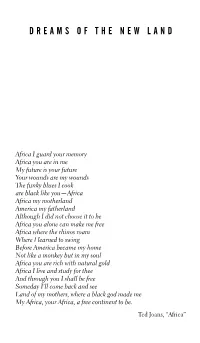

Dreams of the New Land

When History Sleeps: A Beginning 13 DREAMS OF THE NEW LAND Africa I guard your memory Africa you are in me My future is your future Your wounds are my wounds The funky blues I cook are black like you—Africa Africa my motherland America my fatherland Although I did not choose it to be Africa you alone can make me free Africa where the rhinos roam Where I learned to swing Before America became my home Not like a monkey but in my soul Africa you are rich with natural gold Africa I live and study for thee And through you I shall be free Someday I’ll come back and see Land of my mothers, where a black god made me My Africa, your Africa, a free continent to be. Ted Joans, “Africa” 14 Freedom Dreams Schoolhouse Rock didn’t teach me a damn thing about “free- dom.” The kids like me growing up in Harlem during the 1960s and early 1970s heard that word in the streets; it rang in our ears with the regularity of a hit song. Everybody and their mama spoke of freedom, and what they meant usually defied the popular meanings of the day. Whereas most Americans associated free- dom with Western democracies at war against communism, free- market capitalism, or U.S. intervention in countries such as Viet- nam or the Dominican Republic, in our neighborhood “freedom” had no particular tie to U.S. nationality (with the pos- sible exception of the black-owned Freedom National Bank). Freedom was the goal our people were trying to achieve; free was a verb, an act, a wish, a militant demand. -

Tsugiki, a Grafting: the Life and Poetry of a Japanese Pioneer Woman in Washington Columbia Magazine, Spring 2005: Vol

Tsugiki, a Grafting: The Life and Poetry of a Japanese Pioneer Woman in Washington Columbia Magazine, Spring 2005: Vol. 19, No. 1 By Gail M. Nomura In the imagination of most of us, the pioneer woman is represented by a sunbonneted Caucasian traveling westward on the American Plains. Few are aware of the pioneer women who crossed the Pacific Ocean east to America from Japan. Among these Japanese pioneer women were some whose destiny lay in the Pacific Northwest. In Washington, pioneer women from Japan, the Issei or first (immigrant) generation, and their Nisei, second-generation, American-born daughters, made up the largest group of nonwhite ethnic women in the state for most of the first half of the 20th century. These women contributed their labor in agriculture and small businesses to help develop the state’s economy. Moreover, they were essential to the establishment of a viable Japanese American community in Washington. Yet, little is known of the history of these women. What follows is the story of one Japanese pioneer woman, Teiko Tomita. An examination of her life offers insight into the historical experience of other Japanese pioneer women in Washington. Beyond an oral history obtained through interviews, Tomita’s experience is illumined by the rich legacy of tanka poems she wrote since she was a high school girl in Japan. The tanka written by Tomita served as a form of journal for her, a way of expressing her innermost thoughts as she became part of America. Indeed, Tsugiki, the title Tomita gave her section of a poetry anthology, meaning a grafting or a grafted tree, reflects her vision of a Japanese American grafted community rooting itself in Washington through the pioneering experiences of women like herself. -

The Emigrants Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE EMIGRANTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK W. G. Sebald,Michael Hulse | 256 pages | 04 Jul 2011 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099448884 | English | London, United Kingdom The Emigrants PDF Book Netflix and third parties use cookies why? And later, on board a paddle-wheel steamer that is taking them through the Great Lakes to Minnesota, the emigrants in steerage look up in admiration to the rich first-class passengers on the upper deck. No comments yet. They sell everything and embark for the U. Not long afterwards, tragedy strikes again when Danjel's infant daughter dies after a brief illness. The journey on the sailing ship is long and tedious. Director: Jan Troell. Now playing. Reviews The Emigrants. Robert Sven-Olof Bern The Emigrants The New Land. More takes were filmed in May to August Understated, Dark. Available to download. Add the first question. Once Upon a River Roxana Hadadi. Awards for The Emigrants. Not long afterwards, a friend and neighbor of Karl Oskar, Jonas Petter, also expresses an interest of going with them to escape his unhappy marriage. The combined cost of the two films was kr 7 million, then the most expensive Swedish film. New York. Looking for some great streaming picks? Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Meanwhile, Kristina's uncle Danjel Andreasson is being persecuted by the dean for rejecting the official religion and giving fundamentalist religious services in his home. A Ship Loaded with Dreams 48m. Plot Summary. Films directed by Jan Troell. More than 70 industry sessions confirmed to run alongside market and screenings from November Visit our What to Watch page. -

Old New Unknown

Charlotta Forss Charlotta Forss The Old, the New and the Unknown This thesis investigates early modern ways of looking at the world through an analysis of what the continents meant in three settings of knowledge making in seventeenth-century Sweden. Combining text, maps and images, the thesis anal- yses the meaning of the continents in, frst, early modern scholarly ‘geography’, second, accounts of journeys to the Ottoman Empire and, third, accounts of journeys to the colony New Sweden. The investigation explores how an under- standing of conceptual categories such as the continents was intertwined with processes of making and presenting knowledge. In this, the study combines ap- proaches from conceptual history with research on knowledge construction and circulation in the early modern world. The thesis shows how geographical frameworks shifted between settings. There was variation in what the continents meant and what roles they could fll. Rather THE than attribute this fexibility to random variation or mistakes, this thesis inter- The Old, the New and Unknown OLD prets fexibility as an integral part of how the world was conceptualized. Reli- gious themes, ideas about societal unities, defnitions of old, new and unknown knowledge, as well as practical considerations, were factors that in different way shaped what the continents meant. THE NEW A scheme of continents – usually consisting of the entities ‘Africa,’ ‘America,’ ‘Asia,’ ‘Europe’ and the polar regions – is a part of descriptions about what the world looks like today. In such descriptions, the continents are often treated as existing outside of history. However, like other concepts, the meaning and sig- nifcance of these concepts have changed drastically over time and between con- AND THE texts. -

The New Urban Enclosures Stuart Hodkinson Version of Record First Published: 24 Sep 2012

This article was downloaded by: [University of Leeds] On: 24 September 2012, At: 02:10 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccit20 The new urban enclosures Stuart Hodkinson Version of record first published: 24 Sep 2012. To cite this article: Stuart Hodkinson (2012): The new urban enclosures, City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action, 16:5, 500-518 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.709403 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. CITY,VOL. 16, NO.5,OCTOBER 2012 The new urban enclosures Stuart Hodkinson The ongoing crisis of global capitalism has served only to intensify the past four decades of neoliberal restructuring of cities across the world. -

Congressional Record-House. 689

1918. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 689 engaged in the news-print paper bu~iness, as there are bad Alexander D. Pitts to be United States attorney., souther11 men engaged in every otber activity of human endeavor. Does district of Alabama. the Senator finu in any similar ca. es a penalty of three years Thomas -A. Flynn to be United States attorney, district of in prison and $50.000 .fine or both? Does not the Senator think Arizona. that amount might well be reduced and not let it go to the John W. Preston· to be United States attorney, northern dis- world that the e men are such a wicked lot of scoundrels that trict of California. they ought to be dealt with ilifferently from the rest of human John Robert O'Connor to be United States attorney, southern kind? diRtiict of California. _ . 1\ir. Sl\1ITH of Arizona. I have no pride at all about that. Hooper Alexander to be United States attorney, northern dis· and.all tho e matter will rest in the judgment of the Senate. trict of Georgia. \Vhen we come to the final consideration of the measure all James L. McCiear to be United States attorney, district of those things will appeal to me, no doubt, as they will to any Idaho. Senator. Thomas J. Boynton to be United States attorney, district of - l\lr. GALLIKGER. I will tender another amenument now. Massachusetts. 1 move to strike out " $50.000," on page 3, line 24, and insert Francis Fisher Kane to be Unite(] States attorney, eastern "$20,000." Let that be pending. -

Jun & Jul Guide

VISIT home box office HOME mcr. 0161 200 1500 2 Tony Wilson Place DON’T MISS... Manchester org THEATRE ART YOUNG M15 4FN home EXHIBITION/ LA MOVIDA INFORMATION & HOME presents Until Mon 17 Jul PEOPLE ROSE Free, drop in BOOKING Until Sat 10 Jun YOUNG IDENTITY homemcr.org/la-movida HOMEmcr.org Tickets £26.50 - £10 Every Monday, 19:00 0161 200 1500 homemcr.org/rose (excluding Bank Holidays) EXHIBITION TOUR: LA MOVIDA Free, drop in [email protected] Accessible Performances Thu 1 Jun, 18:30 homemcr.org/young-identity BSL Interpreted Free, booking required Tue 6 Jun, 19:30 homemcr.org/la-movida ACCESSIBILITY HOMEmcr.org/accessibility Caption Subtitled HOME PROJECTS: EDEN KÖTTING REGULAR Wed 7 Jun, 19:30 & ANONYMOUS BOSCH TOUCH Audio Described Touch Wed 21 Jun – Sun 30 Jul EVENTS KEEP IN TOUCH TOUR Tour Granada Foundation Galleries 1 & 2 PLAYREADING Twitter @HOME_mcr Thu 8 Jun, 18:30 Free, drop in Fri 2 Jun, 11:00 Facebook HOMEmcr homemcr.org/home-projects Audio Described Fri 7 Jul, 11:00 Instagram HOMEmcr Thu 8 Jun, 19:30 Tickets £5 (scripts and CEREMONY Audioboom HOMEmcr refreshments included) Event/ Playreading: The Shroud PART OF MIF17 homemcr.org/playreading Youtube HOMEmcrorg Maker + Q&A with Palestinian Sun 16 Jul, 18:00 writer Ahmed Masoud Free, booking required JMK RESIDENCY Fri 9 Jun, 19:00 homemcr.org/ceremony OPENING TIMES Wed 7 – Fri 9 Jun, 10:00 – 17:00 Tickets £3 Box Office homemcr.org/shroud-maker Free, application required homemcr.org/jmk-jun Mon – Sun: 12:00 – 20:00 creatives Main Gallery Blast Theory and Hydrocracker MOTHERS -

Filmmaking and Film Studies

Libraries FILMMAKING AND FILM STUDIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 025 Sunset Red DVD-9505 African Violet #1 VHS-3655 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 After Gorbachev's USSR DVD-2615 11 x 14/One Way Boogie Woogie/27 Years Later DVD-9953 Agit-Film VHS-2622 13 Most Beautiful: Songs for Andy Warhol's Screen Tests DVD-2978 Ah, Liberty! VHS-5952 14 Video Paintings DVD-8355 Airport/Airport 1975 DVD-3307 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-1239 Akira DVD-0315 DVD-0260 DVD-1214 25th Hour DVD-2291 Akran DVD-6838 39 Steps DVD-0337 Alaya VHS-1199 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Alexander Nevsky DVD-8367 400 Blows DVD-8362 DVD-4983 56 Up DVD-8322 Alexander Nevsky (Criterion) c.2 DVD-4983 c.2 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 Alexeieff at the Pinboard VHS-3822 A to Z VHS-4494 Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection Bonus DVD-0958 Disc Abbas Kiarostami (Discs 1-4) DVD-6979 Discs 1 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Abbas Kiarostami (Discs 5-8) DVD-6979 Discs 5 Alice DVD-4863 Abbas Kiarostami (Discs 9-10) DVD-6979 Discs 9 Alice c,2 DVD-4863 c.2 Aberration of Light DVD-7584 All My Life VHS-2415 Abstronic VHS-1350 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD-1284 Ace of Light VHS-1123 All that Heaven Allows DVD-0329 Across the Rappahannock VHS-5541 All That Heaven Allows c.2 DVD-0329 c.2 Act of Killing DVD-4434 Alleessi: An African Actress DVD-3247 Adaptation DVD-4192 Alphaville