The Strategic Air Command

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay: the Crew

AFA’s Enola Gay Controversy Archive Collection www.airforcemag.com The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay From the Air Force Association’s Enola Gay Controversy archive collection Online at www.airforcemag.com The Crew The Commander Paul Warfield Tibbets was born in Quincy, Ill., Feb. 23, 1915. He joined the Army in 1937, became an aviation cadet, and earned his wings and commission in 1938. In the early years of World War II, Tibbets was an outstanding B-17 pilot and squadron commander in Europe. He was chosen to be a test pilot for the B-29, then in development. In September 1944, Lt. Col. Tibbets was picked to organize and train a unit to deliver the atomic bomb. He was promoted to colonel in January 1945. In May 1945, Tibbets took his unit, the 509th Composite Group, to Tinian, from where it flew the atomic bomb missions against Japan in August. After the war, Tibbets stayed in the Air Force. One of his assignments was heading the bomber requirements branch at the Pentagon during the development of the B-47 jet bomber. He retired as a brigadier general in 1966. In civilian life, he rose to chairman of the board of Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, retiring from that post in 1986. At the dedication of the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar- Hazy Center in December 2003, the 88-year-old Tibbets stood in front of the restored Enola Gay, shaking hands and receiving the high regard of visitors. (Col. Paul Tibbets in front of the Enola Gay—US Air Force photo) The Enola Gay Crew Airplane Crew Col. -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Cold War Scrapbook Compiled by Frances Mckenney, Assistant Managing Editor

Cold War Scrapbook Compiled by Frances McKenney, Assistant Managing Editor The peace following World War II was short- lived. Soviet forces never went home, kept occupied areas under domination, and threatened free nations worldwide. By 1946, Winston Churchill had declared, “An iron curtain has descended across the conti- nent.” Thus began a 45-year struggle between the diametrically opposed worldviews of the US and the Soviet Union. In 1948, the USSR cut off land access to free West Berlin, launch- ing the first major “battle” of the Cold War: the Berlin Airlift. Through decades of changes in strategy, tactics, locations, and technology, the Air Force was at the forefront. The Soviet Union was contained, and eventually, freedom won out. Bentwaters. Bitburg. Clark. Loring. Soes- terberg. Suwon. Wurtsmith—That so many Cold War bases are no longer USAF instal- lations is a tribute to how the airmen there did their jobs. While with the 333rd Tactical Fighter Training Squadron at Davis-Monthan AFB, Ariz., in 1975, Capt. Thomas McKee asked a friend to take this “hero shot” of him with an A-7. McKee flew the Corsair II as part of Tactical Air Command, at Myrtle Beach AFB, S.C. He was AFA National President and Chairman of the Board (1998-2002). Assigned to the 1st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, Beale AFB, Calif., RSO Maj. Thomas Veltri (right) and Maj. Duane Noll prepare for an SR-71 mission from RAF Mildenhall, UK, in the mid- 1980s. Veltri’s most memora- ble Blackbird sortie: “We lost an engine in the Baltic, north of Gotland Island, and ended up at 25,000 feet, with a dozen MiGs chasing us.” Retired Lt. -

The 341St Missile Wing History

341st Missile Wing History HISTORY OF THE 341 MISSILE WING World War II Bomb Group The 341st Missile Wing began as the 341st Bombardment Group (Medium) in the China-Burma- India (CBI) Theater of World War II. The Group was activated at Camp Malir in Karachi, India on 15 September 1942. The unit was one of the first bomber units in the CBI; being equipped with B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, which were shipped from the United States to Karachi. The aircraft were readied for flight operations by Air Technical Service Command at Karachi Air Depot and dispatched to Chakulia Airfield, now in Bangladesh in December. The group was formed with two bomb squadrons (11th, 22d) which had been attached to the 7th Bombardment Group since May 1942, and two newly activated squadrons (490th and 491st). The 11th Bomb Squadron was already in China, having flown combat missions with China Air Task Force since 1 July 1942. Planes and crews of the 22nd had been flying recon and tactical missions over north and central Burma, also since July. The group entered combat early in 1943 and operated chiefly against enemy transportation in central Burma until 1944. It bombed bridges, locomotives, railroad yards, and other targets to delay movement of supplies to the Japanese troops fighting in northern Burma. 341st Missile Wing History The 341st Bomb Group usually functioned as if it were two groups and for a time as three. Soon after its activation in September 1942, 341st Bomb Group Headquarters and three of its squadrons, the 22nd, 490th and 491st, were stationed and operating in India under direction of the Tenth Air Force, while the 11th squadron was stationed and operating in China under direction of the "China Air Task Force", which was later reorganized and reinforced to become the Fourteenth Air Force. -

Voices from an Old Warrior Why KC-135 Safety Matters

Voices from an Old Warrior Why KC-135 Safety Matters Foreword by General Paul Selva GALLEON’S LAP PUBLISHING ND 2 EDITION, FIRST PRINTING i Hoctor, Christopher J. B. 1961- Voices from an Old Warrior: Why KC-135 Safety Matters Includes bibliographic references. 1. Military art and science--safety, history 2. Military history 3. Aviation--history 2nd Edition – First Printing January 2014 1st Edition (digital only) December 2013 Printed on the ©Espresso Book Machine, Mizzou Bookstore, Mizzou Publishing, University of Missouri, 911 E. Rollins Columbia, MO 65211, http://www.themizzoustore.com/t-Mizzou-Media-About.aspx Copyright MMXIII Galleon's Lap O'Fallon, IL [email protected] Printer's disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author. They do not represent the opinions of Mizzou Publishing, or the University of Missouri. Publisher's disclaimer, rights, copying, reprinting, etc Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author, except where cited otherwise. They do not represent any U.S. Govt department or agency. This book may be copied or quoted without further permission for non-profit personal use, Air Force safety training, or academic research, with credit to the author and Galleon's Lap. To copy/reprint for any other purpose will require permission. Author's disclaimers Sources can be conflicting, especially initial newspaper reports compared to official information released to the public later. Some names may have a spelling error and I apologize for that. I changed many of the name spellings because I occasionally found more definitive sources written by family members. -

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron's

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron’s Experience during the Development of World War II Tactical Air Power by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 14, 2013 Keywords: World War II, fighter squadrons, tactical air power, P-47 Thunderbolt, European Theater of Operations Copyright 2013 by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce Approved by William Trimble, Chair, Alumni Professor of History Alan Meyer, Assistant Professor of History Mark Sheftall, Associate Professor of History Abstract During the years between World War I and World War II, many within the Army Air Corps (AAC) aggressively sought an independent air arm and believed that strategic bombardment represented an opportunity to inflict severe and dramatic damages on the enemy while operating autonomously. In contrast, working in cooperation with ground forces, as tactical forces later did, was viewed as a subordinate role to the army‘s infantry and therefore upheld notions that the AAC was little more than an alternate means of delivering artillery. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a significantly expanded air arsenal and war plan in 1939, AAC strategists saw an opportunity to make an impression. Eager to exert their sovereignty, and sold on the efficacy of heavy bombers, AAC leaders answered the president‘s call with a strategic air doctrine and war plans built around the use of heavy bombers. The AAC, renamed the Army Air Forces (AAF) in 1941, eventually put the tactical squadrons into play in Europe, and thus tactical leaders spent 1943 and the beginning of 1944 preparing tactical air units for three missions: achieving and maintaining air superiority, isolating the battlefield, and providing air support for ground forces. -

The Cold War and Beyond

Contents Puge FOREWORD ...................... u 1947-56 ......................... 1 1957-66 ........................ 19 1967-76 ........................ 45 1977-86 ........................ 81 1987-97 ........................ 117 iii Foreword This chronology commemorates the golden anniversary of the establishment of the United States Air Force (USAF) as an independent service. Dedicated to the men and women of the USAF past, present, and future, it records significant events and achievements from 18 September 1947 through 9 April 1997. Since its establishment, the USAF has played a significant role in the events that have shaped modem history. Initially, the reassuring drone of USAF transports announced the aerial lifeline that broke the Berlin blockade, the Cold War’s first test of wills. In the tense decades that followed, the USAF deployed a strategic force of nuclear- capable intercontinental bombers and missiles that deterred open armed conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. During the Cold War’s deadly flash points, USAF jets roared through the skies of Korea and Southeast Asia, wresting air superiority from their communist opponents and bringing air power to the support of friendly ground forces. In the great global competition for the hearts and minds of the Third World, hundreds of USAF humanitarian missions relieved victims of war, famine, and natural disaster. The Air Force performed similar disaster relief services on the home front. Over Grenada, Panama, and Libya, the USAF participated in key contingency actions that presaged post-Cold War operations. In the aftermath of the Cold War the USAF became deeply involved in constructing a new world order. As the Soviet Union disintegrated, USAF flights succored the populations of the newly independent states. -

Lieutenant General Warren D. Johnson

LIEUTENANT GENERAL WARREN D. JOHNSON Retired April 1, 1977. Lieutenant General Warren D. Johnson is director, Defense Nuclear Agency, Washington, D.C. General Johnson was born in 1922, in Blackwell, Okla. He graduated from Classen High School in Oklahoma City in 1937, and attended Oklahoma City University. He entered military service in April 1942 and graduated from officer candidate school with a commission as second lieutenant in November 1942. His first assignment was with the 9th Armored Division, Fort Riley, Kan. In November 1943 he began flying school at Jackson, Tenn., and completed advanced training and B-17 transition training in 1944. After tours of duty as aide-de-camp to the commanding general at Barksdale Field, La., and Brooks and Biggs fields, Texas, he was sent to Tokyo, Japan, where he served, from December 1946 until June 1949, as a personnel officer in the Pacific Air Command and the Far East Air Forces. Next assigned as a B-36 crewmember with the 11th Bombardment Wing, Carswell Air Force Base, Texas, he began his long association with Strategic Air Command. From December 1950 to August 1954, he served as a personnel officer at SAC headquarters, Offutt Air Force Base, Neb. At Little Rock Air Force Base, Ark., from May 1955 to July 1959, he served as a B-47 aircraft commander, chief of plans, and director of operations for the 70th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing; and director of operations, 825th Air Division. In July 1959, he assumed command of the 340th Bombardment Squadron, Blytheville Air Force Base, Ark., and in June 1960 became deputy commander for operations, 97th Bombardment Wing. -

Historical Handbook of NGA Leaders

Contents Introduction . i Leader Biographies . ii Tables National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Directors . 58 National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Deputy Directors . 59 Defense Mapping Agency Directors . 60 Defense Mapping Agency Deputy Directors . 61 Defense Mapping Agency Directors, Management and Technology . 62 National Photographic Interpretation Center Directors . 63 Central Imagery Office Directors . 64 Defense Dissemination Program Office Directors . 65 List of Acronyms . 66 Index . 68 • ii • Introduction Wisdom has it that you cannot tell the players without a program. You now have a program. We designed this Historical Handbook of National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Leaders as a useful reference work for anyone who needs fundamental information on the leaders of the NGA. We have included those colleagues over the years who directed the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and the component agencies and services that came together to initiate NGA-NIMA history in 1996. The NGA History Program Staff did not celebrate these individuals in this setting, although in reading any of these short biographies you will quickly realize that we have much to celebrate. Rather, this practical book is designed to permit anyone to reach back for leadership information to satisfy any personal or professional requirement from analysis, to heritage, to speechwriting, to retirement ceremonies, to report composition, and on into an endless array of possible tasks that need support in this way. We also intend to use this book to inform the public, especially young people and students, about the nature of the people who brought NGA to its present state of expertise. -

Hill Air Force Base in the 1970S

80 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE HILL AIR FORCE BASE IN THE 1970S June 19, 1970 April 1, 1971 June 1971 December 9, 1971 April 30, 1972 April 30, 1972 January 1, 1973 The first flight of Minuteman III (LGM-30G) Intercontinental Military Airlift Command (MAC) assigned the 1550th Hill AFB implemented the test version of the Advanced Strategic Air Command (SAC) announced designation Hill AFB held a groundbreaking The first F-4E Phantom arrived at Hill AFB for leading edge slats The Reserve 508th Tactical Fighter Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) became operational at Minot AFB, North Aircrew Training and Test Wing (ATTW) and its seven Logistics System (ALS). This third-generation, of Hill AFB as one of six satellite “alert” bases. From ceremony to initiate construction of modification. The depot’s Maintenance Division completed the Group (TFG) activated at Hill AFB, Dakota. Hill AFB shipped the first LGM-30G in a C-141 Starlifter squadrons to Hill AFB. The unit operated on Hill until near-real-time computer system provided timely January 1973 to July 1975, crews from Detachment 1 of a new 11-floor, 120-foot-tall Aircraft first aircraft on April 3, 1973, and a total of 304 aircraft by April assigned the F-105 Thunderchief. after its assembly at Air Force Plant 77 in April 1970. March 15, 1976. information for logistics support to Air Force units. the 456th Bombardment Wing (Heavy) stood alert at Control Tower, completed on March 14, 1976, when this modification program ended. Hill AFB with B-52s. 15, 1974. April 10, 1977 December 20, 1976 December 12, 1975 -

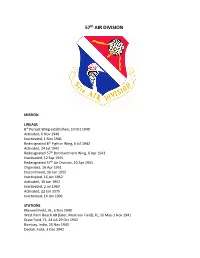

57Th AIR DIVISION

57th AIR DIVISION MISSION LINEAGE 8th Pursuit Wing established, 19 Oct 1940 Activated, 6 Nov 1940 Inactivated, 1 Nov 1941 Redesignated 8th Fighter Wing, 6 Jul 1942 Activated, 24 Jul 1942 Redesignated 57th Bombardment Wing, 6 Apr 1943 Inactivated, 12 Sep 1945 Redesignated 57th Air Division, 10 Apr 1951 Organized, 16 Apr 1951 Discontinued, 16 Jun 1952 Inactivated, 16 Jun 1952 Activated, 16 Jun 1952 Inactivated, 2 Jul 1969 Activated, 22 Jan 1975 Inactivated, 14 Jun 1991 STATIONS Maxwell Field, AL, 6 Nov 1940 West Palm Beach AB (later, Morrison Field), FL, 16 May-1 Nov 1941 Drew Field, FL, 24 Jul-29 Oct 1942 Bombay, India, 29 Nov 1942 Declali, India, 3 Dec 1942 Port Tewfik, Egypt, 22 Dec 1942 Landing Ground 91 (near Cairo), Egypt, 23 Dec 1942 El Kabrit, Egypt, 12 Feb 1943 Deversoir, Egypt, 5 Jun 1943 Tunis, Tunisia, 28 Aug 1943 Lentini, Sicily, 4 Sep 1943 Naples, Italy, 7 Oct 1943 Foggia, Italy, 29 Oct 1943 Trocchia, Italy, 4 Jan 1944 Ghisonaccia, Corsica, 20 Apr 1944 Migliacharo, Corsica, 5 Oct 1944 Fano, Italy, 7 Apr 1945 Pomigliano Staging Airdrome No. 2, Italy, 23 Aug-12 Sep 1945 Fairchild AFB, WA, 16 Apr 1951-16 Jun 1952 Fairchild AFB, WA, 16 Jun 1952 Westover AFB, MA, 4 Sep 1956-2 Jul 1969 Minot AFB, ND, 22 Jan 1975-14 Jun 1991 ASSIGNMENTS General Headquarters Air Force, 6 Nov 1940 Southeast Air District (later, Third Air Force), 16 Jan 1941 Interceptor Command (of Third Air Force), 21 Apr 1941 III Interceptor Command, 1 Jul 1 Nov 1941 IX Fighter Command, 24 Jul 1942 Ninth Air Force, 22 Dec 1942 Twelfth Air Force, 23 Aug 1943 XII Air Support Command, 31 Aug 1943 XII Bomber Command, 1 Jan 1944 Twelfth Air Force, 1 Mar 1944 Army Air Forces Service Command, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, 15 Aug 12 Sep 1945 Fifteenth Air Force, 16 Apr 1951 16 Jun 1952 Fifteenth Air Force, 16 Jun 1952 Eighth Air Force, 4 Sep 1956 2 Jul 1969 Fifteenth Air Force, 22 Jan 1975 14 Jun 1991 ATTACHMENTS III Fighter Command, 26 Jul 28 Oct 1942 IX Fighter Command, 22 Dec 1942-unkn 1943 COMMANDERS Cpt Harold H.