SPRING 2014 - Volume 61, Number 1 the Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twelve Greatest Air Battles of the Tuskegee Airmen

THE TWELVE GREATEST AIR BATTLES OF THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN Daniel L. Haulman, PhD Chief, Organizational Histories Branch Air Force Historical Research Agency 25 January 2010 edition Introduction The 332d Fighter Group was the only African-American group in the Army Air Forces in World War II to enter combat overseas. It eventually consisted of four fighter squadrons, the 99th, 100th, 301st, and 302d. Before the 332d Fighter Group deployed, the 99th Fighter Squadron, had already taken part in combat for many months. The primary mission of the 99th Fighter Squadron before June 1944 was to launch air raids on ground targets or to defend Allied forces on the ground from enemy air attacks, but it also escorted medium bombers on certain missions in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. When the 332d Fighter Group first deployed to Italy in early 1944, it also flew patrol, close air support, and interdiction tactical missions for the Twelfth Air Force. Between early June 1944 and late April 1945, the 332d Fighter Group, which the 99th Fighter Squadron joined, flew a total of 311 missions with the Fifteenth Air Force. The primary function of the group then, along with six other fighter groups of the Fifteenth Air Force, was to escort heavy bombers, including B-17s and B-24s, on strategic raids against enemy targets in Germany, Austria, and parts of Nazi-occupied central, southern, and Eastern Europe. This paper focuses on the twelve greatest air battles of the Tuskegee Airmen. They include the eleven missions in which the 332d Fighter Group, or the 99th Fighter Squadron before deployment of the group, shot down at least four enemy aircraft. -

The War Years

1941 - 1945 George Northsea: The War Years by Steven Northsea April 28, 2015 George Northsea - The War Years 1941-42 George is listed in the 1941 East High Yearbook as Class of 1941 and his picture and the "senior" comments about him are below: We do know that he was living with his parents at 1223 15th Ave in Rockford, Illinois in 1941. The Rockford, Illinois city directory for 1941 lists him there and his occupation as a laborer. The Rockford City Directory of 1942 lists George at the same address and his occupation is now "Electrician." George says in a journal written in 1990, "I completed high school in January of 1942 (actually 1941), but graduation ceremony wasn't until June. In the meantime I went to Los Angeles, California. I tried a couple of times getting a job as I was only 17 years old. I finally went to work for Van De Camp restaurant and drive-in as a bus boy. 6 days a week, $20.00 a week and two meals a day. The waitresses pitched in each week from their tips for the bus boys. That was another 3 or 4 dollars a week. I was fortunate to find a garage apartment a few blocks from work - $3 a week. I spent about $1.00 on laundry and $2.00 on cigarettes. I saved money." (italics mine) "The first part of May, I quit my job to go back to Rockford (Illinois) for graduation. I hitch hiked 2000 miles in 4 days. I arrived at my family's house at 4:00 AM one morning. -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

459Th OPERATIONS GROUP

459th OPERATIONS GROUP MISSION LINEAGE 459th Bombardment Group (Heavy) established, 19 May 1943 Activated, 1 Jul 1943 Redesignated 459th Bombardment Group, Heavy, 20 Aug 1943 Inactivated, 28 Aug 1945 Redesignated 459th Bombardment Group, Very Heavy, 11 Mar 1947 Activated in the Reserve, 19 Apr 1947 Redesignated 459th Bombardment Group, Medium, 27 Jun 1949 Ordered to active service, 1 May 1951 Inactivated, 16 Jun 1951 Redesignated 459th Troop Carrier Group, Medium, 30 Dec 1954 Activated in the Reserve, 26 Jan 1955 Inactivated, 14 Apr 1959 Redesignated 459th Tactical Airlift Group, 31 Jul 1985 Redesignated 459th Operations Group and activated in the Reserve, 1 Aug 1992 STATIONS Alamogordo AAFld, NM, 1 Jul 1943 Davis-Monthan Fld, AZ, 28 Jul 1943 Kearns, UT, 31 Aug 1943 Davis-Monthan Fld, AZ, 21 Sep 1943 Westover Fld, MA, 31 Oct 1943-3 Jan 1944 Guilia Afld, Cerignola, Italy, 12 Feb 1944-c Jul 1945 SiouX Falls AAFld, SD, 16-28 Aug 1945 Long Beach AAFld, CA, 19 Apr 1947 Davis-Monthan AFB, AZ, 27 Jun 1949-16 Jun 1951 Andrews AFB, MD, 26 Jan 1955-14 Apr 1959 Andrews AFB, MD, 1 Aug 1992 ASSIGNMENTS Second Air Force, 1 Jul 1943 First Air Force, 31 Oct 1943 304th Bombardment Wing, 25 Jan 1944 Second Air Force, 13-28 Aug 1945 304th Bombardment Wing (later, 304th Air Division), 19 Apr 1947 Eighth Air Force, 27 Jun 1949 Fifteenth Air Force, 1 Apr 1950-16 Jun 1951 459th Troop Carrier Wing, 26 Jan 1955-14 Apr 1959 459th Airlift Wing, 1 Aug 1992 WEAPON SYSTEMS B-24, 1943-1945 T-6, 1947-1949 T-7, 1947-1949 T-11, 1947-1949 Unkn, 1949-1951 C-45, 1955-1958 C-46, 1955-1957 C-119, 1957-1959 C-141, 1992 COMMANDERS Col Marden M. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Extraordinary Technology

Extraordinary Technology: The Ceire® Device Charles Vincent Biddy iUniverse Project ID number 730290 to be Published 2017 ISBN: 123456789 ISBN: 1234567 © Rocky Mountain Research Inc 2016 Extraordinary Technology The Ceire Device Charles Vincent Biddy iUniverse Old Chinese proverb "Down hill easy, Uphill, much puffing.” Old Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times.” Contents Foreword Chapter 1 Operational principles Chapter 2: Calculating forward thrust Chapter 3: Eliminating Reverse thrust Chapter 4: Other Implementations Chapter 5: Applications References Appendix Control, The 3rd derivative of position The Forth law of motion (Analog 69(3): 83-104 (May 1962) Foreword Fundamentally, science must be a series of successive approximations to reality. It simply is not possible to arrive at absolute truth with a small number of investigations. Physics at the freshman level is a very straightforward subject. Facts are well known, relationships are stated in forthright terms without equivocation, and there is little room for doubt. It takes three years or more, and perhaps graduate school before it finally dawns on a budding scientist that the whole structure of science, so monumental when viewed from a distance, is a cracked and sagging edifice held together with masking tape and resting on the shifting sands of constantly changing theory. Very little is known with any real certainty. Some things are merely more probable than others. Well-known theories and even laws turn out to be only partially confirmed hypotheses, waiting to be replaced with somewhat better partially confirmed hypotheses. If there is one thing we know about every theory in modern physics as taught in public schools today, it is that it is wrong, or at least incomplete. -

Biography of the HONORABLE RICHARD DEAN ROGERS Senior United States District Judge by Homer E. Socolofsky

r Biography of THE HONORABLE RICHARD DEAN ROGERS Senior United States District Judge r By Homer E. Socolofsky 1 1 Copyright © 1995 by The United States District Court, Kansas District This biography is made available for research purposes. All rights to the biography, including the right to publish, are reserved to the United States District Court, District of Kansas. No part of the biography may be quoted for publication without the permission of the Court. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Clerk of the Court, United States District Court, District of Kansas, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. ff^ It is recommended that this biography be cited as follows: Richard DeanDean Rogers, Rogers, "Biography "Biography of the of Honorable the Honorable Richard RichardDean Rogers, Dean Senior Rogers, United Senior States United States "1 District Judge,*Judge," aa historyhistory prepared 1994-1995 by Homer Socolofsky, United States District Court, DistrictT C i a + T »of i # Kansas, * + 1995. A f l T o n e o o 1 Q O R - > Printed in U.SA. by Mennonite Press, Inc., Newton, Kansas 67114 'v.r The Honorable Richard Dean Rogers | in m ftp) PI TTie United States District Court gratefully ^1 acknowledges the contributions of the Kansas Federal Bar jpt v. W\ spp ifS 1*1 53} p The Honorable Richard Dean Rogers - r r r r r The Honorable Richard Dean Rogers vii ipfy ij$B| Preface wi legal terms and procedure in extended tape- 1B^ last December, inviting me to write recorded sessions. -

Voices from an Old Warrior Why KC-135 Safety Matters

Voices from an Old Warrior Why KC-135 Safety Matters Foreword by General Paul Selva GALLEON’S LAP PUBLISHING ND 2 EDITION, FIRST PRINTING i Hoctor, Christopher J. B. 1961- Voices from an Old Warrior: Why KC-135 Safety Matters Includes bibliographic references. 1. Military art and science--safety, history 2. Military history 3. Aviation--history 2nd Edition – First Printing January 2014 1st Edition (digital only) December 2013 Printed on the ©Espresso Book Machine, Mizzou Bookstore, Mizzou Publishing, University of Missouri, 911 E. Rollins Columbia, MO 65211, http://www.themizzoustore.com/t-Mizzou-Media-About.aspx Copyright MMXIII Galleon's Lap O'Fallon, IL [email protected] Printer's disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author. They do not represent the opinions of Mizzou Publishing, or the University of Missouri. Publisher's disclaimer, rights, copying, reprinting, etc Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author, except where cited otherwise. They do not represent any U.S. Govt department or agency. This book may be copied or quoted without further permission for non-profit personal use, Air Force safety training, or academic research, with credit to the author and Galleon's Lap. To copy/reprint for any other purpose will require permission. Author's disclaimers Sources can be conflicting, especially initial newspaper reports compared to official information released to the public later. Some names may have a spelling error and I apologize for that. I changed many of the name spellings because I occasionally found more definitive sources written by family members. -

Lieutenant General Warren D. Johnson

LIEUTENANT GENERAL WARREN D. JOHNSON Retired April 1, 1977. Lieutenant General Warren D. Johnson is director, Defense Nuclear Agency, Washington, D.C. General Johnson was born in 1922, in Blackwell, Okla. He graduated from Classen High School in Oklahoma City in 1937, and attended Oklahoma City University. He entered military service in April 1942 and graduated from officer candidate school with a commission as second lieutenant in November 1942. His first assignment was with the 9th Armored Division, Fort Riley, Kan. In November 1943 he began flying school at Jackson, Tenn., and completed advanced training and B-17 transition training in 1944. After tours of duty as aide-de-camp to the commanding general at Barksdale Field, La., and Brooks and Biggs fields, Texas, he was sent to Tokyo, Japan, where he served, from December 1946 until June 1949, as a personnel officer in the Pacific Air Command and the Far East Air Forces. Next assigned as a B-36 crewmember with the 11th Bombardment Wing, Carswell Air Force Base, Texas, he began his long association with Strategic Air Command. From December 1950 to August 1954, he served as a personnel officer at SAC headquarters, Offutt Air Force Base, Neb. At Little Rock Air Force Base, Ark., from May 1955 to July 1959, he served as a B-47 aircraft commander, chief of plans, and director of operations for the 70th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing; and director of operations, 825th Air Division. In July 1959, he assumed command of the 340th Bombardment Squadron, Blytheville Air Force Base, Ark., and in June 1960 became deputy commander for operations, 97th Bombardment Wing. -

Me 262 P-51 MUSTANG Europe 1944–45

Me 262 P-51 MUSTANG Europe 1944–45 ROBERT FORSYTH Me 262 P-51 Mustang Europe 1944–45 ROBERT FORSYTH CONTENTS Introduction 4 Chronology 8 Design and Development 10 Technical Specifications 25 The Strategic Situation 35 The Combatants 42 Combat 55 Statistics and Analysis 74 Aftermath 76 Further Reading 79 Index 80 INTRODUCTION In the unseasonably stormy summer skies of July 28, 1943, the USAAF’s Eighth Air Force despatched 302 B‑17 Flying Fortresses to bomb the Fieseler aircraft works at Kassel‑Batteshausen and the AGO aircraft plant at Oschersleben, both in Germany. This was the “Mighty Eighth’s” 78th such mission to Europe since the start of its strategic bombing operations from bases in England in August of the previous year. On this occasion, for the first time, and at least for a part of their journey into the airspace of the Reich, the bombers would enjoy the security and protection of P‑47 Thunderbolt escort fighters. The latter had been fitted with bulky and unpressurized auxiliary fuel tanks that were normally used for ferry flights, but which greatly extended their usual range. Yet even with this extra fuel, the P‑47s could only stay with the bombers for part of their journey. Herein lay a dichotomy. Despite warnings to the contrary from their Royal Air Force (RAF) counterparts, senior staff officers in the USAAF believed in the viability of undertaking future unescorted daylight missions to key targets within Germany. In January 1943 Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt met in Casablanca to determine a plan for Allied victory. -

Historical Handbook of NGA Leaders

Contents Introduction . i Leader Biographies . ii Tables National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Directors . 58 National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Deputy Directors . 59 Defense Mapping Agency Directors . 60 Defense Mapping Agency Deputy Directors . 61 Defense Mapping Agency Directors, Management and Technology . 62 National Photographic Interpretation Center Directors . 63 Central Imagery Office Directors . 64 Defense Dissemination Program Office Directors . 65 List of Acronyms . 66 Index . 68 • ii • Introduction Wisdom has it that you cannot tell the players without a program. You now have a program. We designed this Historical Handbook of National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Leaders as a useful reference work for anyone who needs fundamental information on the leaders of the NGA. We have included those colleagues over the years who directed the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and the component agencies and services that came together to initiate NGA-NIMA history in 1996. The NGA History Program Staff did not celebrate these individuals in this setting, although in reading any of these short biographies you will quickly realize that we have much to celebrate. Rather, this practical book is designed to permit anyone to reach back for leadership information to satisfy any personal or professional requirement from analysis, to heritage, to speechwriting, to retirement ceremonies, to report composition, and on into an endless array of possible tasks that need support in this way. We also intend to use this book to inform the public, especially young people and students, about the nature of the people who brought NGA to its present state of expertise. -

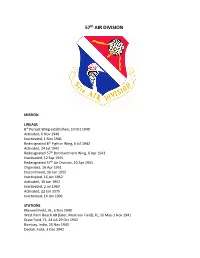

57Th AIR DIVISION

57th AIR DIVISION MISSION LINEAGE 8th Pursuit Wing established, 19 Oct 1940 Activated, 6 Nov 1940 Inactivated, 1 Nov 1941 Redesignated 8th Fighter Wing, 6 Jul 1942 Activated, 24 Jul 1942 Redesignated 57th Bombardment Wing, 6 Apr 1943 Inactivated, 12 Sep 1945 Redesignated 57th Air Division, 10 Apr 1951 Organized, 16 Apr 1951 Discontinued, 16 Jun 1952 Inactivated, 16 Jun 1952 Activated, 16 Jun 1952 Inactivated, 2 Jul 1969 Activated, 22 Jan 1975 Inactivated, 14 Jun 1991 STATIONS Maxwell Field, AL, 6 Nov 1940 West Palm Beach AB (later, Morrison Field), FL, 16 May-1 Nov 1941 Drew Field, FL, 24 Jul-29 Oct 1942 Bombay, India, 29 Nov 1942 Declali, India, 3 Dec 1942 Port Tewfik, Egypt, 22 Dec 1942 Landing Ground 91 (near Cairo), Egypt, 23 Dec 1942 El Kabrit, Egypt, 12 Feb 1943 Deversoir, Egypt, 5 Jun 1943 Tunis, Tunisia, 28 Aug 1943 Lentini, Sicily, 4 Sep 1943 Naples, Italy, 7 Oct 1943 Foggia, Italy, 29 Oct 1943 Trocchia, Italy, 4 Jan 1944 Ghisonaccia, Corsica, 20 Apr 1944 Migliacharo, Corsica, 5 Oct 1944 Fano, Italy, 7 Apr 1945 Pomigliano Staging Airdrome No. 2, Italy, 23 Aug-12 Sep 1945 Fairchild AFB, WA, 16 Apr 1951-16 Jun 1952 Fairchild AFB, WA, 16 Jun 1952 Westover AFB, MA, 4 Sep 1956-2 Jul 1969 Minot AFB, ND, 22 Jan 1975-14 Jun 1991 ASSIGNMENTS General Headquarters Air Force, 6 Nov 1940 Southeast Air District (later, Third Air Force), 16 Jan 1941 Interceptor Command (of Third Air Force), 21 Apr 1941 III Interceptor Command, 1 Jul 1 Nov 1941 IX Fighter Command, 24 Jul 1942 Ninth Air Force, 22 Dec 1942 Twelfth Air Force, 23 Aug 1943 XII Air Support Command, 31 Aug 1943 XII Bomber Command, 1 Jan 1944 Twelfth Air Force, 1 Mar 1944 Army Air Forces Service Command, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, 15 Aug 12 Sep 1945 Fifteenth Air Force, 16 Apr 1951 16 Jun 1952 Fifteenth Air Force, 16 Jun 1952 Eighth Air Force, 4 Sep 1956 2 Jul 1969 Fifteenth Air Force, 22 Jan 1975 14 Jun 1991 ATTACHMENTS III Fighter Command, 26 Jul 28 Oct 1942 IX Fighter Command, 22 Dec 1942-unkn 1943 COMMANDERS Cpt Harold H.