February 1991 February

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1456 HON. PAUL E. KANJORSKI HON. LINCOLN DIAZ-BALART

E1456 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks July 27, 2001 of public authorities in Romania should be al- JOSEPH ‘‘RED’’ JONES HONORED 26 OF JULY MOVEMENT together ended. It is time—and past time—for these simple steps to be taken. HON. LINCOLN DIAZ-BALART As Chairman-in-Office, Minister Geoana has HON. PAUL E. KANJORSKI OF FLORIDA repeatedly expressed his concern about the OF PENNSYLVANIA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES trafficking of human beings into forced pros- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES titution and other forms of slavery in the Friday, July 27, 2001 OSCE region. The OSCE has proven to be an Friday, July 27, 2001 Mr. DIAZ-BALART. Mr. Speaker, yesterday effective forum for addressing this particular Mr. KANJORSKI. Mr. Speaker, I rise today marked another anniversary of the tragic human rights violation, and I commend Min- to call the attention of the House of Rep- events of July 26, 1953, when Fidel Castro, ister Geoana for maintaining the OSCE’s resentatives to the long history of service to along with a band of supporters, attacked a focus on the issue. the community by my good friend, Joseph military barracks in eastern Cuba in order to Domestically, Romania is also in a position ‘‘Red’’ Jones of Luzerne County, Pennsyl- make a name for himself, causing the deaths to lead by example in combating trafficking. of dozens of Cubans in what will doubtless be Notwithstanding that the State Department’s vania. Red will be honored with a tribute on August 17, 2001, the 50th anniversary of his considered as a national day of mourning in first annual Trafficking in Persons report char- Cuban history. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

O Socialismo E O Intelectual Em Cuba: Negociações E Transgressões No Jornalismo E Na Literatura De Leonardo Padura (1979-2018)

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM BRUNA TELLA GUERRA O socialismo e o intelectual em Cuba: negociações e transgressões no jornalismo e na literatura de Leonardo Padura (1979-2018) CAMPINAS 2019 BRUNA TELLA GUERRA O socialismo e o intelectual em Cuba: negociações e transgressões no jornalismo e na literatura de Leonardo Padura (1979-2018) Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do título de Doutora em Teoria e História Literária, na área de Teoria e Crítica Literária. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Francisco Foot Hardman ESTE TRABALHO CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA TESE DEFENDIDA POR BRUNA TELLA GUERRA E ORIENTADA PELO PROFESSOR DR. FRANCISCO FOOT HARDMAN. CAMPINAS 2019 Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem Leandro dos Santos Nascimento - CRB 8/8343 Guerra, Bruna Tella, 1987- G937s GueO socialismo e o intelectual em Cuba : negociações e transgressões no jornalismo e na literatura de Leonardo Padura (1979-2018) / Bruna Tella Guerra. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2019. GueOrientador: Francisco Foot Hardman. GueTese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. Gue1. Padura, Leonardo, 1955- - Crítica e interpretação. 2. Literatura latino- americana. 3. Literatura cubana. 4. Jornalismo e literatura. 5. Imprensa. I. Hardman, Francisco Foot. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. III. Título. -

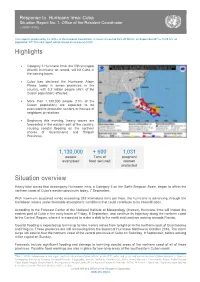

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Revista 29 Índice

REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA Nº 29 Otoño 2007 Madrid Octubre-Diciembre 2007 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA HC DIRECTOR Javier Martínez-Corbalán REDACCIÓN Orlando Fondevila Begoña Martínez CONSEJO EDITORIAL Cristina Álvarez Barthe, Elías Amor, Luis Arranz, Mª Elena Cruz Varela, Jorge Dávila, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ángel Esteban del Campo, Roberto Fandiño, Alina Fernández, Mª Victoria Fernández- Ávila, Celia Ferrero, Carlos Franqui, José Luis González Quirós, Mario Guillot, Guillermo Gortázar, Jesús Huerta de Soto, Felipe Lázaro, Jacobo Machover, José Mª Marco, Julio San Francisco, Juan Morán, Eusebio Mujal-León, Fabio Murrieta, José Luis Prieto Bena- vent, Tania Quintero, Alberto Recarte, Raúl Rivero, Ángel Rodríguez Abad, José Antonio San Gil, José Sanmartín, Pío Serrano, Daniel Silva, Álvaro Vargas Llosa, Alejo Vidal-Quadras. Esta revista es miembro de ARCE Asociación de Revistas Culturales de España Esta revista es miembro de la Federación Iberoamericana de Revistas Culturales (FIRC) Esta revista ha recibido una ayuda de la Dirección General del Libro, Archivos y Bibliotecas para su difusión en bibliotecas, centros culturales y universidades de España. EDITA, F. H. C. C/ORFILA, 8, 1ºA - 28010 MADRID Tel: 91 319 63 13/319 70 48 Fax: 91 319 70 08 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.revistahc.org Suscripciones: España: 24 Euros al año. Otros países: 60 Euros al año, incluído correo aéreo. Precio ejemplar: España 8 Euros. Los artículos publicados en esta revista, expresan las opiniones y criterios de sus autores, sin que necesariamente sean atribuibles a la Revista Hispano Cubana HC. EDICIÓN Y MAQUETACIÓN, Visión Gráfica DISEÑO, C&M FOTOMECÁNICA E IMPRESIÓN, Campillo Nevado, S.A. ISSN: 1139-0883 DEPÓSITO LEGAL: M-21731-1998 SUMARIO EDITORIAL CRÓNICAS DESDE CUBA -2007: Verano de fuego Félix Bonne Carcassés 7 -La ventana indiscreta Rafael Ferro Salas 10 -Eleanora Rafael Ferro Salas 11 -El Gatopardo cubano Félix Bonne Carcassés 14 DOSSIER: EL PRESIDIO POLÍTICO CUBANO -La infamia continua y silenciada. -

Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From: Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject: Situation Report No. 6 “Hurricane IKE”- September 16, 2008- 18:00 hrs. Situation: A report published today, September 16, by the official newspaper Granma with preliminary data on the damages caused by hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE asserts that they are estimated at 5 billion USD. The data provided below is a summary of official data. Pinar del Río Cienfuegos 25. Ciego de Ávila 38. Jesús Menéndez 1. Viñales 14. Aguada de Pasajeros 26. Baraguá Holguín 2. La palma 15. Cumanayagua Camagüey 39. Gibara 3. Consolación Villa Clara 27. Florida 40. Holguín 4. Bahía Honda 16. Santo Domingo 28. Camagüey 41. Rafael Freyre 5. Los palacios 17. Sagüa la grande 29. Minas 42. Banes 6. San Cristobal 18. Encrucijada 30. Nuevitas 43. Antilla 7. Candelaria 19. Manigaragua 31. Sibanicú 44. Mayarí 8. Isla de la Juventud Sancti Spíritus 32. Najasa 45. Moa Matanzas 20. Trinidad 33. Santa Cruz Guantánamo 9. Matanzas 21. Sancti Spíritus 34. Guáimaro 46. Baracoa 10. Unión de Reyes 22. La Sierpe Las Tunas 47. Maisí 11. Perico Ciego de Ávila 35. Manatí 12. Jagüey Grande 23. Managua 36. Las Tunas 13. Calimete 24. Venezuela 37. Puerto Padre Calle 18 No. 110, Miramar, La Habana, Cuba, Apdo 4138, Tel: (537) 204 1513, Fax (537) 204 1516, [email protected], www.onu.org.cu 1 Cash donations in support of the recovery efforts, can be made through the following bank account opened by the Government of Cuba: Account Number: 033473 Bank: Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI) Account Title: MINVEC Huracanes restauración de daños Measures adopted by the Government of Cuba: The High Command of Cuba’s Civil Defense announced that it will activate its centers in all of Cuba to direct the rehabilitation of vital services that have been disrupted by the impact of Hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE. -

Revista Hispano Cubana Hc

revista 11 índice, editorial 3/10/03 15:20 Página 1 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA Nº 11 Otoño 2001 Madrid Octubre-Diciembre 2001 revista 11 índice, editorial 3/10/03 15:20 Página 2 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA HC DIRECTOR Guillermo Gortázar REDACTORA JEFE Yolanda Isabel González REDACCIÓN Mª Victoria Fernández-Ávila Celia Ferrero Orlando Fondevila CONSEJO EDITORIAL Cristina Álvarez Barthe, Luis Arranz, Mª Elena Cruz Varela, Jorge Dávila, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ángel Esteban del Campo, Alina Fernández, Carlos Franqui, José Luis González Quirós, Mario Guillot, Jesús Huerta de Soto, Felipe Lázaro, César Leante, Jacobo Machover, José Mª Marco, Javier Martínez-Corbalán, Julio Martínez, Eusebio Mujal-León, Mario Parajón, José Luis Prieto Benavent, Tania Quintero, Alberto Recarte, Raúl Rivero, Ángel Rodríguez Abad, Eugenio Rodríguez Chaple, José Antonio San Gil, José Sanmartín, Pío Serrano, Daniel Silva, Rafael Solano, Álvaro Vargas Llosa, Alejo Vidal-Quadras. Esta revista es Esta revista es miembro de ARCE miembro de la Asociación de Federación Revistas Culturales Iberoamericana de de España Revistas Culturales (FIRC) EDITA, F. H. C. C/ORFILA, 8, 1ºA - 28010 MADRID Tel: 91 319 63 13/319 70 48 Fax: 91 319 70 08 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.revistahc.com Suscripciones: España: 3000 ptas. al año. Otros países: 6500 ptas. (45 U.S. $) al año, incluído correo aéreo. Precio ejemplar: España 1000 ptas. Extranjero: 7 U.S. $ Los artículos publicados en esta revista, expresan las opiniones y criterios de sus autores, sin que necesariamente sean atribuibles a la Revista Hispano Cubana HC. EDICIÓN Y MAQUETACIÓN, Visión Gráfica DISEÑO, C&M FOTOMECÁNICA E IMPRESIÓN, Campillo Nevado, S.A. -

31 Desde Europa

Los verdaderos héroes La muerte de Fidel Castro obliga a contrastar sus panegíricos con los testimonios de quiénes lo adversaron y son los verdaderos héroes cubanos que el mundo debería admirar. O deja de sorprender la ola de elogios a la figura de Fidel Castro y el carácter planetario Nque se ha reservado a su desaparición. Era previsible. Es el resultado del inmenso capital que invirtió desde los comienzos de su irrupción en el escenario político cubano. Es de hecho una de sus obras mayores: la creación de su propio personaje. Genio de la propaganda política, forjador de su propia imagen, político convertido en actor, la presencia ava- salladora del cuerpo expuesto en actitud incitadora al afecto, la performance antes de que existiera este género que hoy cunde en el mundo. Fidel Castro logró imponer su imagen hasta conver- tirla en parte del imaginario colectivo de allí que no le importara, durante el período senil de su vida, mostrar su decadencia física. Los diarios y los semanarios europeos vienen repletos de galerías de fotos del caudillo cubano durante los momentos estelares de su vida. Las del anciano de los últimos años, han desapa- recido del escenario. Para América Latina, la influencia del castrismo ha significado una involución de la democracia en el El ex preso político Diaz, con Elizabeth Burgos: fue continente. De hecho, desde la llegada de Fidel Castro condenado a 40 años de cárcel cumplio 22 y fue libera- al poder en 1959, la historia de América Latina se ha do. Su relato de lo vivido en cautiverio es estremecedor. -

Sweig, Julia. Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground

ACHSC / 32 / Romero Sweig, Julia. Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Harvard University Press, 2002. 254 páginas. Susana Romero Sánchez Estudiante, Maestría en Historia Universidad Nacional de Colombia Inside the Cuban Revolution es uno de los últimos trabajos sobre la revolución cubana, incluso se ha dicho que es el definitivo, escrito por la investigadora en relaciones internacionales con América Latina y Cuba, Julia Sweig, del Consejo para las Relaciones Internacionales de Estados Unidos y de la Universidad John Hopkins. El libro trata a la revolución cubana desde dentro (como su título lo insinúa), es decir, narra la historia del Movimiento 26 de julio (M267) –sus conflictos y sus disputas internas; mientras, paralelamente, explica cómo ese movimiento logró liderar la oposición a Fulgencio Batista y cómo se produjo el proceso revolucionario, en un período que comprende desde los primeros meses de 1957 hasta la formación del primer gabinete del gobierno revolucionario, durante los primeros días de enero de 1959. En lo que respecta a la historia del 26 de julio, la autora se preocupa principalmente de la relación entre las fuerzas del llano y de la sierra, y sobre el proceso revolucionario, el libro profundiza en cómo el M267 se convirtió en la fuerza más popular de la oposición y en su relación con las demás organizaciones. Uno de los grandes aportes de Sweig es que logra poner en evidencia fuentes documentales cubanas, a las cuales ningún investigador había podido tener acceso con anterioridad. Esas nuevas fuentes consisten en el fondo documental Celia Sánchez, de la Oficina de Asuntos Históricos de La Habana, el cual contiene correspondencia entre los dirigentes –civiles y militares–1 del Movimiento 26 de julio, informes y planes operacionales durante la “lucha contra la tiranía”, es decir, desde que Fulgencio Batista dio el golpe de estado a Carlos Prío Socarrás, el 10 de marzo de 1952, hasta el triunfo de la revolución cubana, en enero de 1959. -

Environmental Law in Cuba

ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN CUBA OLIVER A. HOUCK*1 Table of Contents Prologue .................................................................................................1 I. A View of the Problem ...................................................................3 II. Institutions and the Law..................................................................8 III. The Environmental Awakening .....................................................13 IV. The Agency, The Strategy and Law 81...........................................18 A. CITMA ..................................................................................19 B. The National Environmental Strategy .......................................21 C. Law 81, the Law of the Environment ........................................23 V. Environmental Impact Analysis .....................................................25 A. What and When......................................................................27 B. Who .......................................................................................31 C. Alternatives ............................................................................34 D. Review...................................................................................35 VI. Coastal Zone Management............................................................38 VII. Biological Diversity ......................................................................47 VIII. Implementation ............................................................................57 IX. The Economy -

Freedom of the Press 2017 Cuba

Cuba Page 1 of 5 Published on Freedom House (https://freedomhouse.org) Home > Cuba Cuba Country: Cuba Year: 2017 Press Freedom Status: Not Free PFS Score: 91 Legal Environment: 28 Political Environment: 35 Economic Environment: 28 Key Developments in 2016: • A number of Cuban and foreign journalists were detained or arrested around the time of U.S. president Barack Obama’s historic visit to Cuba in March. • In June, young state journalists from Santa Clara circulated a letter protesting censorship, low salaries, and political persecution, initiated after they were told by the official Union of Journalists of Cuba (UPEC) to stop collaborating with the independent online magazine OnCuba. • In October, a reporter with the independent Hablemos Press news agency was detained ahead of his scheduled flight to Trinidad and Tobago, preventing him from participating in a journalism workshop there. • Independent outlets, which are technically illegal but tolerated if they do not cross certain red lines, continued to open and expand. Executive Summary Cuba has the most repressive media environment in the Americas. Traditional news media are owned and controlled by the state, which uses outlets to promote its political goals and deny a voice to the opposition. Journalists not employed by state media operate https://freedomhouse.org/print/49545 1/12/2018 Cuba Page 2 of 5 in a legal limbo—they are technically illegal, yet tolerated unless they cross ill-defined lines. Journalists at both state and independent media risk harassment, intimidation, and detention in connection with any coverage perceived as critical of authorities or of Cuba’s political system. -

Revista Hispano Cubana

revista 16 índice 6/10/03 12:14 Página 1 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA Nº 16 Primavera-Verano 2003 Madrid Mayo-Septiembre 2003 revista 16 índice 6/10/03 12:14 Página 2 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA HC DIRECTOR Javier Martínez-Corbalán REDACCIÓN Celia Ferrero Orlando Fondevila Begoña Martínez CONSEJO EDITORIAL Cristina Álvarez Barthe, Luis Arranz, Mª Elena Cruz Varela, Jorge Dávila, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ángel Esteban del Campo, Alina Fernández, Mª Victoria Fernández-Ávila, Carlos Franqui, José Luis González Quirós, Mario Guillot, Guillermo Gortázar Jesús Huerta de Soto, Felipe Lázaro, Jacobo Machover, José Mª Marco, Julio San Francisco, Juan Morán, Eusebio Mujal-León, Fabio Murrieta, Mario Parajón, José Luis Prieto Benavent, Tania Quintero, Alberto Recarte, Raúl Rivero, Ángel Rodríguez Abad, José Antonio San Gil, José Sanmartín, Pío Serrano, Daniel Silva, Rafael Solano, Álvaro Vargas Llosa, Alejo Vidal-Quadras. Esta revista es Esta revista es miembro de ARCE miembro de la Asociación de Federación Revistas Culturales Iberoamericana de de España Revistas Culturales (FIRC) EDITA, F. H. C. C/ORFILA, 8, 1ºA - 28010 MADRID Tel: 91 319 63 13/319 70 48 Fax: 91 319 70 08 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.revistahc.com Suscripciones: España: 24 Euros al año. Otros países: 58 Euros al año, incluído correo aéreo. Precio ejemplar: España 8 Euros. Los artículos publicados en esta revista, expresan las opiniones y criterios de sus autores, sin que necesariamente sean atribuibles a la Revista Hispano Cubana HC. EDICIÓN Y MAQUETACIÓN, Visión Gráfica DISEÑO,