Experimental Histamine Pruritus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

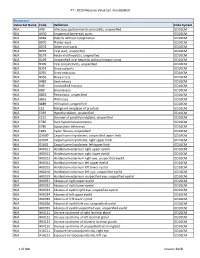

PT - 2020 Measure Value Set Avoidableed

PT - 2020 Measure Value Set_AvoidableED Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System N/A A09 Infectious gastroenteritis and colitis, unspecified ICD10CM N/A A630 Anogenital (venereal) warts ICD10CM N/A B069 Rubella without complication ICD10CM N/A B070 Plantar wart ICD10CM N/A B078 Other viral warts ICD10CM N/A B079 Viral wart, unspecified ICD10CM N/A B179 Acute viral hepatitis, unspecified ICD10CM N/A B199 Unspecified viral hepatitis without hepatic coma ICD10CM N/A B309 Viral conjunctivitis, unspecified ICD10CM N/A B354 Tinea corporis ICD10CM N/A B355 Tinea imbricata ICD10CM N/A B356 Tinea cruris ICD10CM N/A B483 Geotrichosis ICD10CM N/A B49 Unspecified mycosis ICD10CM N/A B80 Enterobiasis ICD10CM N/A B852 Pediculosis, unspecified ICD10CM N/A B853 Phthiriasis ICD10CM N/A B889 Infestation, unspecified ICD10CM N/A C61 Malignant neoplasm of prostate ICD10CM N/A E039 Hypothyroidism, unspecified ICD10CM N/A E215 Disorder of parathyroid gland, unspecified ICD10CM N/A E780 Pure hypercholesterolemia ICD10CM N/A E786 Lipoprotein deficiency ICD10CM N/A E849 Cystic fibrosis, unspecified ICD10CM N/A G5600 Carpal tunnel syndrome, unspecified upper limb ICD10CM N/A G5601 Carpal tunnel syndrome, right upper limb ICD10CM N/A G5602 Carpal tunnel syndrome, left upper limb ICD10CM N/A H00011 Hordeolum externum right upper eyelid ICD10CM N/A H00012 Hordeolum externum right lower eyelid ICD10CM N/A H00013 Hordeolum externum right eye, unspecified eyelid ICD10CM N/A H00014 Hordeolum externum left upper eyelid ICD10CM N/A H00015 Hordeolum externum -

2U11/13U195 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date Χ n n 20 October 2011 (20.10.2011) 2U11/13U195 Al (51) International Patent Classification: ka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 1-7-1, Dosho-machi, Chuo- C12P 19/34 (2006.01) C07H 21/04 (2006.01) ku, Osaka-shi, Osaka 541-0045 (JP). (21) International Application Number: (74) Agents: KELLOGG, Rosemary et al; Swanson & PCT/US201 1/032017 Bratschun, L.L.C., 8210 SouthPark Terrace, Littleton, Colorado 80120 (US). (22) International Filing Date: 12 April 201 1 (12.04.201 1) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, English (25) Filing Language: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (26) Publication Language: English CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (30) Priority Data: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, 61/323,145 12 April 2010 (12.04.2010) US KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (71) Applicants (for all designated States except US): SOMA- ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, LOGIC, INC. [US/US]; 2945 Wilderness Place, Boulder, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, Colorado 80301 (US). OTSUKA PHARMACEUTI¬ SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, CAL CO., LTD. -

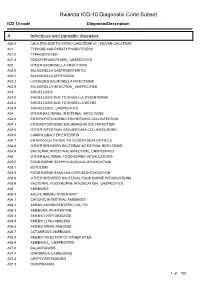

Rwanda ICD-10 Diagnostic Code Subset

Rwanda ICD-10 Diagnostic Code Subset ICD 10 code Diagnosis/Description A Infectious and parasitic diseases A00.0 CHOLERA DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 01_ BIOVAR CHOLERAE A01 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS A01.0 TYPHOID FEVER A01.4 PARATYPHOID FEVER_ UNSPECIFIED A02 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS A02.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS A02.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICEMIA A02.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS A02.9 SALMONELLA INFECTION_ UNSPECIFIED A03 SHIGELLOSIS A03.0 SHIGELLOSIS DUE TO SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE A03.2 SHIGELLOSIS DUE TO SHIGELLA BOYDII A03.9 SHIGELLOSIS_ UNSPECIFIED A04 OTHER BACTERIAL INTESTINAL INFECTIONS A04.0 ENTEROPATHOGENIC ESCHERICHIA COLI INFECTION A04.1 ENTEROTOXIGENIC ESCHERICHIA COLI INFECTION A04.4 OTHER INTESTINAL ESCHERICHIA COLI INFECTIONS A04.5 CAMPYLOBACTER ENTERITIS A04.7 ENTEROCOLITIS DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE A04.8 OTHER SPECIFIED BACTERIAL INTESTINAL INFECTIONS A04.9 BACTERIAL INTESTINAL INFECTION_ UNSPECIFIED A05 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD-BORNE INTOXICATIONS A05.0 FOOD-BORNE STAPHYLOCOCCAL INTOXICATION A05.1 BOTULISM A05.4 FOOD-BORNE BACILLUS CEREUS INTOXICATION A05.8 OTHER SPECIFIED BACTERIAL FOOD-BORNE INTOXICATIONS A05.9 BACTERIAL FOOD-BORNE INTOXICATION_ UNSPECIFIED A06 AMEBIASIS A06.0 ACUTE AMEBIC DYSENTERY A06.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMEBIASIS A06.2 AMEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS A06.3 AMEBOMA OF INTESTINE A06.4 AMEBIC LIVER ABSCESS A06.5 AMEBIC LUNG ABSCESS A06.6 AMEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS A06.7 CUTANEOUS AMEBIASIS A06.8 AMEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES A06.9 AMEBIASIS_ UNSPECIFIED A07.0 BALANTIDIASIS A07.1 GIARDIASIS [LAMBLIASIS] -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0038462 A1 ZHANG Et Al

US 20160038462A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0038462 A1 ZHANG et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 11, 2016 (54) USE OF NK-1 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS IN (60) Provisional application No. 61/838,784, filed on Jun. PRURTUS 24, 2013. (71) Applicant: TIGERCAT PHARMA, INC., South Publication Classification San Francisco, CA (US) (51) Int. Cl. (72) Inventors: Xiaoming ZHANG, Sunnyvale, CA A613 L/403 (2006.01) (US); Edward F. SCHNIPPER, A6II 45/06 (2006.01) Redwood City, CA (US); Andrew J. A619/00 (2006.01) PERLMAN, Stanford, CA (US); James (52) U.S. Cl. W. LARRICK, Sunnyvale, CA (US) CPC ............. A6 IK3I/403 (2013.01); A61 K9/0053 (2013.01); A61 K9/0014 (2013.01); A61 K (21) Appl. No.: 14/922,684 45/06 (2013.01) (57) ABSTRACT (22)22) Filed: Oct. 26,9 2015 The invention relates to methods for treatingg pruritusp with NK-1 receptor antagonists such as serlopitant. The invention O O further relates to pharmaceutical compositions comprising Related U.S. Application Data NK-1 receptorantagonists such as serlopitant. In addition, the (60) Division of application No. 14/312.942, filed on Jun. invention encompasses treatment of a pruritus-associated 24, 2014, now Pat. No. 9,198.898, which is a continu condition with serlopitant and an additional antipruritic ation-in-part of application No. 13/925,509, filed on agent, and the use of serlopitant as a sleep aid, optionally in Jun. 24, 2013, now Pat. No. 8,906,951. combination with an additional sleep-aiding agent. Patent Application Publication Feb. -

190.18 - Serum Iron Studies

Medicare National Coverage Determinations (NCD) Coding Policy Manual and Change Report (ICD-10-CM) 190.18 - Serum Iron Studies HCPCS Codes (Alphanumeric, CPT AMA) Code Description 82728 Ferritin 83540 Iron 83550 Iron Binding capacity 84466 Transferrin ICD-10-CM Codes Covered by Medicare Program The ICD-10-CM codes in the table below can be viewed on CMS’ website as part of Downloads: Lab Code List, at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/CoverageGenInfo/LabNCDsICD10.html Code Description A01.00 Typhoid fever, unspecified A01.01 Typhoid meningitis A01.02 Typhoid fever with heart involvement A01.03 Typhoid pneumonia A01.04 Typhoid arthritis A01.05 Typhoid osteomyelitis A01.09 Typhoid fever with other complications A01.1 Paratyphoid fever A A01.2 Paratyphoid fever B A01.3 Paratyphoid fever C A01.4 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified A02.0 Salmonella enteritis A02.1 Salmonella sepsis A02.20 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified NCD 190.18 January 2021 Changes ICD-10-CM Version – Red Fu Associates, Ltd. January 2021 1 Medicare National Coverage Determinations (NCD) Coding Policy Manual and Change Report (ICD-10-CM) Code Description A02.21 Salmonella meningitis A02.22 Salmonella pneumonia A02.23 Salmonella arthritis A02.24 Salmonella osteomyelitis A02.25 Salmonella pyelonephritis A02.29 Salmonella with other localized infection A02.8 Other specified salmonella infections A02.9 Salmonella infection, unspecified A04.0 Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection A04.1 Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection A04.2 Enteroinvasive Escherichia -

Dermatology in Geriatrics a Gandhi, M Gandhi, S Kalra

The Internet Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology ISPUB.COM Volume 5 Number 2 Dermatology in Geriatrics A Gandhi, M Gandhi, S Kalra Citation A Gandhi, M Gandhi, S Kalra. Dermatology in Geriatrics. The Internet Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology. 2009 Volume 5 Number 2. Abstract Over the past few years the world's population has continued on its remarkable transition from a state of high birth and death rates to one characterized by low birth and death rates. Consequently, primary care physicians and dermatologists will see more elderly patients presenting age related dermatological conditions.As people age, their chances of developing skin-related disorders increase due to multiple underlying medical conditions i.e. diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis and decreased immunity. Common skin disorders found in the elderly individual are xerosis, pruritus, eczematous dermatitis, purpura, chronic venous insufficiency, psychocutaneous disorders etc. Caregivers and medical personnel can help decrease or prevent the development of many skin disorders in the elderly by addressing several factors i.e patient’s nutritional status, medical history, current medications, allergies, physical limitations, mental state, and personal hygiene and for specific underlying etiologies; several pharmacological treatment choices are suggested. INTRODUCTION and assisted living facilities3 .Caregivers and medical The famous old saying OLD IS GOLD doesn’t apply to personnel can help decrease or prevent the development of human skin as elderly people are recognized by their many skin disorders in the elderly by addressing several wrinkled and dull skin. The population is getting older, with factors i.e patient’s nutritional state, medical history, current a greater percentage of the population in the over-65 age medications, allergies, physical limitations, mental state, and group. -

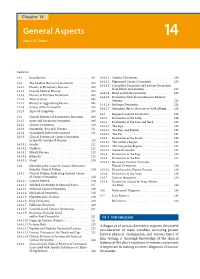

General Aspects 14 Niels K

14_199_254* 05.11.2005 10:15 Uhr Seite 201 Chapter 14 General Aspects 14 Niels K. Veien Contents 14.1 Introduction . 201 14.4.2.1 Cement Ulcerations . 224 14.4.2.2 Pigmented Contact Dermatitis . 225 14.2 The Medical History of the Patient . 202 14.4.2.3 Caterpillar Dermatitis and Irritant Dermatitis 14.2.1 History of Hereditary Diseases . 202 from Plants and Animals . 225 14.2.2 General Medical History . 202 14.4.2.4 Head and Neck Dermatitis . 225 14.2.3 History of Previous Dermatitis . 203 14.4.2.5 Dermatitis from Transcutaneous Delivery 14.2.4 Time of Onset . 203 Systems . 225 14.2.5 History of Aggravating Factors . 204 14.4.2.6 Berloque Dermatitis . 226 14.2.6 Course of the Dermatitis . 205 14.4.2.7 Stomatitis due to Mercury or Gold Allergy . 226 14.2.7 Types of Symptoms . 205 14.5 Regional Contact Dermatitis . 226 14.3 Clinical Features of Eczematous Reactions . 206 14.5.1 Dermatitis of the Scalp . 226 14.3.1 Acute and Recurrent Dermatitis . 206 14.5.2 Dermatitis of the Face and Neck . 228 14.3.2 Chronic Dermatitis . 210 14.5.2.1 The Lips . 230 14.3.3 Nummular (Discoid) Eczema . 211 14.5.2.2 The Eyes and Eyelids . 230 14.3.4 Secondarily Infected Dermatitis . 211 14.5.2.3 The Ear . 231 14.3.5 Clinical Features of Contact Dermatitis 14.5.3 Dermatitis of the Trunk . 232 in Specific Groups of Persons . 212 14.5.3.1 The Axillary Region . -

Id Reaction Associated with Red Tattoo Ink

CASE LETTER Id Reaction Associated With Red Tattoo Ink Alexandra Price, MD; Masoud Tavazoie, MD, PhD; Shane A. Meehan, MD; Marie Leger, MD, PhD 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular PRACTICE POINTS lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. • Hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption the rise due to the increasing popularity and preva- confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo lence of tattoos. Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to • Id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or several of the lesionscopy on the right dorsal foot with some autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant benefit; however, a few days later she developed a gener- to an initial site of infection or sensitization. alized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdo- • Further investigation of color additives in tattoo pig- men, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable ments is warranted to better elucidate the compo- only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known nents responsible for cutaneous allergic reactions drugnot allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any associated with tattoo ink. medications prior to the onset of the eruption. Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema To the Editor: Doconfined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). -

1 Skin Infections Among Elderly Living in Long-Term Care Facilities

1 Skin Infections Among Elderly Living in Long-term Care Facilities Michelle K. Kotti, BSN, MSN, FNP-BC University of Texas at Austin Introduction In the U.S. today, the population of individuals who are 65 years of age and older is increasing (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018), and nurses, as frontline health care providers, are increasingly becoming a conduit for healthy senior living. This module therefore focuses specifically on adults ≥65 years of age with skin infections, a healthcare concern that is especially important among those who are living in long-term care facilities (LTCF). Recent articles on cutaneous infections among those in LCTF are few; indeed more studies of skin infections have been conducted in Europe and Asia than in the U.S. Cutaneous infections are the third most common infection diagnosed in LTCF, preceded only by respiratory infections and infections of the urinary tract (Jump et al., 2008). The cutaneous infections commonly mentioned are cellulitis, angular cheilitis, folliculitis, fungal infections, impetigo, herpes simplex/zoster, and scabies (de Castro & Ramos-e-Silva, 2018). In addition, the skin reflects individuals’ internal health, with a unique and sensitive ability to present manifestations of underlying diseases and even malignancy (Hall, 2006). As a result, the information provided here may lead to additional questions, but it will facilitate our ability to recognize the early signs and symptoms of skin infections so that we can make a difference. Prevention is one of the best defenses. Of course the many health issues associated with the aging process and the immune system’s decline can be a challenge as well (de Castro & Ramos-e-Silva, 2018). -

The Clinical Conundrum of Pruritus Victoria Garcia-Albea, Karen Limaye

FEATURE ARTICLE The Clinical Conundrum of Pruritus Victoria Garcia-Albea, Karen Limaye ABSTRACT: Pruritus is a common complaint for derma- Pruritus is also the most common symptom in derma- tology patients. Diagnosing the cause of pruritus can tological disease and can be a symptom of several sys- be difficult and is often frustrating for patients and pro- temic diseases (Bernhard, 1994). The overall incidence viders. Even after the diagnosis is made, it can be a chal- of pruritus is unknown because there are no epidemio- lenge to manage and relieve pruritus. This article reviews logical databases for pruritus (Norman, 2003). According common and uncommon causes of pruritus and makes to a 2003 study, pruritus and xerosis are the most com- recommendations for proper and thorough evaluation mon dermatological problems encountered in nursing and management. home patients (Norman, 2003). Key words: Itch, Pruritus INTRODUCTION ETIOLOGY Pruritus (itch) is the most frequent symptom in derma- The skin is equipped with a network of afferent sensory tology (Serling, Leslie, & Maurer, 2011). Itch is the pre- and efferent autonomic nerve branches that respond to dominant symptom associated with acute and chronic various chemical mediators found in the skin (Bernhard, cutaneous disease and is a major symptom in systemic dis- 1994). It is believed that maximal itch production is ease (Elmariah & Lerner, 2011; Steinhoff, Cevikbas, Ikoma, achieved at the basal layer of the epidermis, below which & Berger, 2011). It can be a frustration for both the patient pain is perceived (Bernhard, 1994). Autonomic nerves in- and the clinician. This article will attempt to provide an nervate hair follicles, pili erector muscles, blood vessels, overview of pruritus, a method for thorough and com- eccrine, apocrine, and sebaceous glands (Bernhard, 1994). -

Mallory Prelims 27/1/05 1:16 Pm Page I

Mallory Prelims 27/1/05 1:16 pm Page i Illustrated Manual of Pediatric Dermatology Mallory Prelims 27/1/05 1:16 pm Page ii Mallory Prelims 27/1/05 1:16 pm Page iii Illustrated Manual of Pediatric Dermatology Diagnosis and Management Susan Bayliss Mallory MD Professor of Internal Medicine/Division of Dermatology and Department of Pediatrics Washington University School of Medicine Director, Pediatric Dermatology St. Louis Children’s Hospital St. Louis, Missouri, USA Alanna Bree MD St. Louis University Director, Pediatric Dermatology Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital St. Louis, Missouri, USA Peggy Chern MD Department of Internal Medicine/Division of Dermatology and Department of Pediatrics Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis, Missouri, USA Mallory Prelims 27/1/05 1:16 pm Page iv © 2005 Taylor & Francis, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group First published in the United Kingdom in 2005 by Taylor & Francis, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2 Park Square, Milton Park Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7017 6000 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7017 6699 Website: www.tandf.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Although every effort has been made to ensure that all owners of copyright material have been acknowledged in this publication, we would be glad to acknowledge in subsequent reprints or editions any omissions brought to our attention. -

Blood Glucose Testing 2020.Pdf

National Coverage Determination Procedure Code: 82947, 82948, 82962 Blood Glucose Testing CMS Policy Number: 190.20 See also: Medicare Preventive Services Back to NCD List Description: This policy is intended to apply to blood samples used to determine glucose levels. Blood glucose determination may be done using whole blood, serum or plasma. It may be sampled by capillary puncture, as in the fingerstick method, or by vein puncture or arterial sampling. The method for assay may be by color comparison of an indicator stick, by meter assay of whole blood or a filtrate of whole blood, using a device approved for home monitoring, or by using a laboratory assay system using serum or plasma. The convenience of the meter or stick color method allows a patient to have access to blood glucose values in less than a minute or so and has become a standard of care for control of blood glucose, even in the inpatient setting. Indications: Blood glucose values are often necessary for the management of patients with diabetes mellitus, where hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia are often present. They are also critical in the determination of control of blood glucose levels in patient with impaired fasting glucose (FPG 110-125 mg/dL), patient with insulin resistance syndrome and/or carbohydrate intolerance (excessive rise in glucose following ingestion of glucose/glucose sources of food), in patient with a hypoglycemia disorder such as nesidioblastosis or insulinoma, and in patients with a catabolic or malnutrition state. In addition to conditions listed, glucose testing may be medically necessary in patients with tuberculosis, unexplained chronic or recurrent infections, alcoholism, coronary artery disease (especially in women), or unexplained skin conditions (i.e.: pruritis, skin infections, ulceration and gangrene without cause).