Bulgarella Et Al MS-661.Fm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report 1. Darwin Project Information Project title Establishment of Penguin Monitoring Programme Country(ies) Chile Contractor Environmental Research Unit Project Reference No. 162/9/007 Grant Value £10,350 p.a. for 3 years Start/Finishing dates April 2001 to March 2004 Reporting period April 2003 2. Project Background • Briefly describe the location and circumstances of the project and the problem that the project aims to tackle. The project takes place on Magdalena Island, near the city of Punta Arenas in southern Chile. Magdalena Island is one of Chile’s most important breeding sites for Magellanic penguins, a species whose global distribution is restricted to southern South America. Best guess estimates put the current world population of Magellanic penguins at around 1.5 million breeding pairs, with approximately 700,000 pairs in Chile, 650,000 pairs in Argentina and 150,000 pairs in the Falkland Islands (Bingham 1998, Bingham & Mejias 1999, Gandini et al. 1998). Population studies in the Falkland Islands conducted by Mike Bingham have revealed an 80% decline in Magellanic penguins between 1990/91 and 2002/03. A reduction of fish and squid resulting from large-scale commercial fishing appears to be the cause of the penguin decline, through reduction of foraging rates, breeding success and juvenile survival (Bingham 2002). Population studies conducted in Argentina show evidence of decline at some colonies, but not all (Boersma 1997). Declines in Argentina appear to be largely the result of high adult and juvenile mortality caused by oil pollution. An estimated 40,000 Magellanic penguins are killed by oil pollution every year along the coast of Argentina, representing the main cause of adult mortality (Gandini et al. -

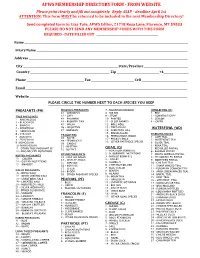

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Parallel Evolution in the Major Haemoglobin Genes of Eight Species of Andean Waterfowl

Molecular Ecology (2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04352.x Parallel evolution in the major haemoglobin genes of eight species of Andean waterfowl K. G. M C CRACKEN,* C. P. BARGER,* M. BULGARELLA,* K. P. JOHNSON,† S. A. SONSTHAGEN,* J. TRUCCO,‡ T. H. VALQUI,§– R. E. WILSON,* K. WINKER* and M. D. SORENSON** *Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, and University of Alaska Museum, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA, †Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, USA, ‡Patagonia Outfitters, Perez 662, San Martin de los Andes, Neuque´n 8370, Argentina, §Centro de Ornitologı´a y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Sta. Rita 117, Urbana Huertos de San Antonio, Surco, Lima 33, Peru´, –Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA, **Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA Abstract Theory predicts that parallel evolution should be common when the number of beneficial mutations is limited by selective constraints on protein structure. However, confirmation is scarce in natural populations. Here we studied the major haemoglobin genes of eight Andean duck lineages and compared them to 115 other waterfowl species, including the bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) and Abyssinian blue-winged goose (Cyanochen cyanopterus), two additional species living at high altitude. One to five amino acid replacements were significantly overrepresented or derived in each highland population, and parallel substitutions were more common than in simulated sequences evolved under a neutral model. Two substitutions evolved in parallel in the aA subunit of two (Ala-a8) and five (Thr-a77) taxa, and five identical bA subunit substitutions were observed in two (Ser-b4, Glu-b94, Met-b133) or three (Ser-b13, Ser-b116) taxa. -

Bleaker Island Settlement & the South

Distance: 1.5 - 2 km Time: 30-45 min Terrain: Moderate 1 SETTLEMENT TRAIL 89 Semaphore Hill This short trail is ideal for families and provides a great introduction to the immediate area. Taking in whale bones, settlement buildings and gardens, the walk also provides a glimpse into farming life with the chance to watch farm activities such as shearing or cattle work if the time is right. It includes a short climb to the Shearing shed summit of Bleaker’s highest hill, an altitude of just 27m (89 feet), giving views across the island and surrounding ocean. 1 Main route Settlement Walk first to the BBQ hut in front of Cassard House. BBQ hut Take time to admire the “Essence of our Community” Imperial artwork on the south-facing wall then go through the gate cormorants Long to see a full Sei whale skeleton, above the beach, nestled 0 100 200 300 400 500 Gulch into the green. 2 Meters From here a route can usually be picked out along the Rockhopper shore in a northerly direction towards the shearing shed Short Gulch penguins and stock yards, taking in a pretty little bay with a variety First Is. of birds. If the weather is very wet and the shoreline muddy, Pebbly Bay an alternative is to walk back through the gate by the Tips: bar-b-que hut, down through the low valley via the wind Ask if anything is happening on the farm, to turbine and solar panels, then through two time the walk accordingly, but remember to gates along a clear track. -

Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Anatini (Surface-Feeding Ducks)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences January 1965 Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Anatini (Surface-feeding Ducks) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscihandwaterfowl Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior: Tribe Anatini (Surface-feeding Ducks)" (1965). Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard. 16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscihandwaterfowl/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Subfamily Anatinae 125 Aix. During extreme excitement the male will often roll his head on his back, or even bathe. I have not observed Preening-behind-the- wing, but W. von de Wall (pers. comm.) has observed a male per- form it toward a female. Finally, Wing-flapping appears to be used as a display by males, and it is especially conspicuous because each sequence of it is ended by a rapid stretching of both wings over the back in a posture that makes visible the white axillary feathers, which contrast sharply with the black underwing surface. Copulatory behavior. Precopulatory behavior consists of the male swimming up to the female, his neck stretched and his crest de- pressed, and making occasional Bill-dipping movements. He then suddenly begins to perform more vigorous Head-dipping movements, and the female, if receptive, performs similar Bill-dipping or Head- dipping movements. -

1 Expedition Report: Jason Islands 1

Expedition Report: Jason Islands 1. Logistics 1.1 Vessel: Golden Fleece , Capt. Dion Poncet 1.2 Expedition dates: 23 Oct 2008 – 4 Nov 2008 1.3 Expedition participants: Karen Neely [email protected] Paul Brickle [email protected] Wetjens Dimmlich [email protected] Judith Brown jbrown@smsg -falklands.org Vlad Laptikhovsky [email protected] Dion Poncet [email protected] Steve Cartwright [email protected] Sarah Crofts [email protected] Vernon Steen [email protected] Claire Goodwin [email protected] Jen Jones [email protected] 2. Scientific rationale and objectives The inshore marine systems and resources of the Falkland Islands make up one of the nation’s most diverse, unique, and valuable assets. From its historical reputation as a safe harbour to its present dependence on fishing and wildlife-based revenues, this archipelago is defined by the sea and its resources. Though perhaps best known ecologically for its bird life, the islands hold numerous organisms and environments that are all closely linked. Of the ten bird species of global conservation concern that breed within the Falklands, eight are seabirds and two are closely associated with offshore islands that contain seabird colonies. These species rely on the marine productivity of the waters around the Falkland Islands and in turn cycle nutrients among the soils, plants, and invertebrates of coastal areas. Knowledge and management of the marine environments are thus important for the knowledge and management of all Falklands ecosystems. Surprisingly, very little of the Islands’ immense coastline has been the subject of scientifically sound investigation, and identification of shallow marine species and habitat types is still in its infancy. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of Anseriformes Based on Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 339–356 www.academicpress.com A molecular phylogeny of anseriformes based on mitochondrial DNA analysis Carole Donne-Goussee,a Vincent Laudet,b and Catherine Haanni€ a,* a CNRS UMR 5534, Centre de Genetique Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 16 rue Raphael Dubois, Ba^t. Mendel, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France b CNRS UMR 5665, Laboratoire de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, 45 Allee d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 5 June 2001; received in revised form 4 December 2001 Abstract To study the phylogenetic relationships among Anseriformes, sequences for the complete mitochondrial control region (CR) were determined from 45 waterfowl representing 24 genera, i.e., half of the existing genera. To confirm the results based on CR analysis we also analyzed representative species based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). These data allowed us to construct a robust phylogeny of the Anseriformes and to compare it with existing phylogenies based on morphological or molecular data. Chauna and Dendrocygna were identified as early offshoots of the Anseriformes. All the remaining taxa fell into two clades that correspond to the two subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae. Within Anserinae Branta and Anser cluster together, whereas Coscoroba, Cygnus, and Cereopsis form a relatively weak clade with Cygnus diverging first. Five clades are clearly recognizable among Anatinae: (i) the Anatini with Anas and Lophonetta; (ii) the Aythyini with Aythya and Netta; (iii) the Cairinini with Cairina and Aix; (iv) the Mergini with Mergus, Bucephala, Melanitta, Callonetta, So- materia, and Clangula, and (v) the Tadornini with Tadorna, Chloephaga, and Alopochen. -

UK-First-Breeding-Register.Pdf

INTRODUCTION TO EDITION The original author and compiler of this record, Dave Coles has devoted a great deal of his time in creating a unique reference document which I am privileged to continue working with. By its very nature the document in a living project which will continue to grow and evolve and I can only hope and wish that I have the dedication as Dave has had in ensuring the continuity of the “First Breeding Register”. Initially all my additions and edits will be indicated in italics though this will not be used in the main body of the record (when a new record is added). Simon Matthews (2011) It is over eighty years since Emilius Hopkinson collated his RECORDS OF BIRDS BRED IN CAPTIVITY, which formed the starting point for my attempt at recording first breeding records for the UK. Since the first edition of my records was published in 1986, classification has changed several times and the present edition incorporates this up-dated classification as well as first breeding recorded since then. The research needed to produce the original volume took many years to complete and covered most avicultural literature. Since that time numerous people have kept me abreast of further breedings and pointing out those that have slipped the net. This has hopefully enabled the records to be kept up-to- date. To those I would express my thanks as indeed I do to all that have cast their eyes over the new list and passed comments, especially the ever helpful Reuben Girling who continues to pass on enquiries. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Contents, Preface, & Introduction Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Contents, Preface, & Introduction" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DUCKS, GEESE, and SWANS of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Revised Edition Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World By Paul A. Johnsgard The only one-volume comprehensive survey of the family Anatidae available in English, this book combines lavish illustration with the most recent information on the natural history, current distribution and status, and identification of all the species. After an introductory discussion of the ten tribes of Anatidae, separate accounts follow for each of the nearly 150 recognized species. These include scientific and vernacular names (in French, German, and Spanish as well as English), descrip- tions of the distribution of all recognized subspecies, selected weights and mea- surements, and identification criteria for both sexes and various age classes. -

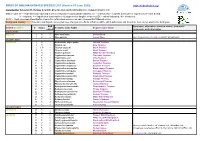

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Selecting Ducks Jacquie Jacob and Tony Pescatore, Animal and Food Sciences

COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND ENVIRONMENT, LEXINGTON, KY, 40546 ASC-198 Selecting Ducks Jacquie Jacob and Tony Pescatore, Animal and Food Sciences s with many domesticated have a body like a duck; they nest, Table 1. Comparison of breeds of species, ducks are selected for attack predators and hiss like a ducks recognized by the American differentA purposes, primarily meat goose; they roost like a chicken; Poultry Association Weight/lb Eggs/ or egg production. They are also and they have a plump breast like Breed Female Male year valued for their feathers and down. a turkey. Muscovies are believed to Aylesbury 8-9 9-10 40-60 It is important to choose a breed of have originated in South America. Buff 6-7 7-8 60-100 duck that best suits your particular They are still found wild in the Call 1.12-1.25 1.38-1.62 20-50 needs. warm regions of South America Campbell 3.5-4.0 4.0-4.5 200-300 The different breeds of ducks are and are raised domestically Cayuga 6-7 7-8 60-100 believed to have originated from throughout the world. In southern Crested 5-6 6-7 60-100 East Indie 1.38-1.50 1.62-1.88 20-50 the wild Mallard (Anas platy- Europe and North Africa they are Magpie 4.0-4.5 4.5-5.0 30-60 rhynchos). The male Mallard has referred to as the Barbary duck. In Mallard 1.88-2.25 2.25-2.50 20-50 a couple of curled tail feathers re- Brazil they are the Brazilian duck, Muscovy 6-7 10-12 60-120 ferred to as the sex feathers (Figure and in the Guianas the Guinea or Pekin 8-9 9-10 100-180 1).