Dr.Noora A.Awad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comp 3, Unit 7 Lecture a Audio Transcript

Audio Transcript Terminology in Healthcare and Public Health Settings Endocrine System Lecture a Health IT Workforce Curriculum Version 4.0/Spring 2016 This material (Comp 3 Unit 7) was developed by the University of Alabama at Birmingham, funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology under Award Number 90WT00007. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Slide 1 Welcome to Terminology in Healthcare and Public Health Settings, Endocrine System. This is lecture A, Overview of the Endocrine System, Adrenal Glands and Pancreas. In this lecture, we will be studying the endocrine system. A doctor who treats diseases of the endocrine system is called an endocrinologist. Slide 2 The objectives for the Endocrine System are to: Define, understand and correctly pronounce medical terms related to the endocrine system. Describe common diseases and conditions with an overview of various treatments related to the endocrine system. Slide 3 The endocrine system is composed of eight endocrine glands that assist in regulating our body’s activities. The endocrine glands are found in various locations throughout our body as we will see in a minute. The actions of the endocrine glands also have effects throughout the body. All endocrine glands secrete “hormones,” or chemical messengers, directly into the bloodstream where they are transported to cells that are waiting for their messages. These hormones help your body respond to stress, regulate your blood pressure, and regulate your water and salt balance. -

Diseases of the Digestive System (KOO-K93)

CHAPTER XI Diseases of the digestive system (KOO-K93) Diseases of oral cavity, salivary glands and jaws (KOO-K14) lijell Diseases of pulp and periapical tissues 1m Dentofacial anomalies [including malocclusion] Excludes: hemifacial atrophy or hypertrophy (Q67.4) K07 .0 Major anomalies of jaw size Hyperplasia, hypoplasia: • mandibular • maxillary Macrognathism (mandibular)(maxillary) Micrognathism (mandibular)( maxillary) Excludes: acromegaly (E22.0) Robin's syndrome (087.07) K07 .1 Anomalies of jaw-cranial base relationship Asymmetry of jaw Prognathism (mandibular)( maxillary) Retrognathism (mandibular)(maxillary) K07.2 Anomalies of dental arch relationship Cross bite (anterior)(posterior) Dis to-occlusion Mesio-occlusion Midline deviation of dental arch Openbite (anterior )(posterior) Overbite (excessive): • deep • horizontal • vertical Overjet Posterior lingual occlusion of mandibular teeth 289 ICO-N A K07.3 Anomalies of tooth position Crowding Diastema Displacement of tooth or teeth Rotation Spacing, abnormal Transposition Impacted or embedded teeth with abnormal position of such teeth or adjacent teeth K07.4 Malocclusion, unspecified K07.5 Dentofacial functional abnormalities Abnormal jaw closure Malocclusion due to: • abnormal swallowing • mouth breathing • tongue, lip or finger habits K07.6 Temporomandibular joint disorders Costen's complex or syndrome Derangement of temporomandibular joint Snapping jaw Temporomandibular joint-pain-dysfunction syndrome Excludes: current temporomandibular joint: • dislocation (S03.0) • strain (S03.4) K07.8 Other dentofacial anomalies K07.9 Dentofacial anomaly, unspecified 1m Stomatitis and related lesions K12.0 Recurrent oral aphthae Aphthous stomatitis (major)(minor) Bednar's aphthae Periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens Recurrent aphthous ulcer Stomatitis herpetiformis 290 DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM Diseases of oesophagus, stomach and duodenum (K20-K31) Ill Oesophagitis Abscess of oesophagus Oesophagitis: • NOS • chemical • peptic Use additional external cause code (Chapter XX), if desired, to identify cause. -

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Its Pharmacotherapy, And

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Its Pharmacotherapy, and Adrenal Gland Dysfunction: A Nationwide Population-Based Study in Taiwan Pin-Han Peng 1, Meng-Yun Tsai 2, Sheng-Yu Lee 3,4 , Po-Cheng Liao 5, Yu-Chiau Shyu 5,6,7,* and Liang-Jen Wang 8,* 1 Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung 833, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung 833, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Graduate Institute of Medicine, School of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 807, Taiwan 5 Community Medicine Research Center, Keelung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung 204, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Department of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan City 333, Taiwan 7 Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan 8 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung 833, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.-C.S.); [email protected] (L.-J.W.) Received: 24 March 2020; Accepted: 20 May 2020; Published: 25 May 2020 Abstract: This study aims to examine the co-occurrence rate of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and adrenal gland disorders, as well as whether pharmacotherapy may affect ADHD patients’ risk of developing adrenal gland disorder. One group of patients newly diagnosed with ADHD (n = 75,247) and one group of age- and gender-matching controls (n = 75,247) were chosen from Taiwan0s National Health Insurance database during the period of January 1999 to December 2011. -

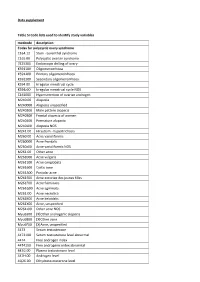

Data Supplement Table SI Code Lists Used to Identify Study Variables

Data supplement Table SI Code lists used to identify study variables medcode description Codes for polycystic ovary syndrome C164.12 Stein - Leventhal syndrome C165.00 Polycystic ovarian syndrome 7E25300 Endoscopic drilling of ovary K591100 Oligomenorrhoea K591200 Primary oligomenorrhoea K591300 Secondary oligomenorrhoea K594.00 Irregular menstrual cycle K594z00 Irregular menstrual cycle NOS C161000 Hypersecretion of ovarian androgen M240.00 Alopecia M240000 Alopecia unspecified M240200 Male pattern alopecia M240300 Frontal alopecia of women M240400 Premature alopecia M240z00 Alopecia NOS M241.00 Hirsutism - hypertrichosis M260.00 Acne varioliformis M260000 Acne frontalis M260z00 Acne varioliformis NOS M261.00 Other acne M261000 Acne vulgaris M261100 Acne conglobata M261600 Cystic acne M261A00 Pustular acne M261E00 Acne excoriee des jeunes filles M261F00 Acne fulminans M261G00 Acne agminata M261J00 Acne necrotica M261K00 Acne keloidalis M261X00 Acne, unspecified M261z00 Other acne NOS Myu6300 [X]Other androgenic alopecia Myu6800 [X]Other acne Myu6F00 [X]Acne, unspecified 4473 Serum testosterone 4473100 Serum testosterone level abnormal 4474 Free androgen index 4474100 Free androgenic index abnormal 447G.00 Plasma testosterone level 447H.00 Androgen level 4Q26.00 Dihydrotestosterone level 4Q2E.00 Free testosterone level 4Q2F.00 Calculated free testosterone ZRBs.00 Ferriman and Galwey score K53..11 Ovarian cysts K532.00 Other ovarian cysts K532z00 Ovarian cyst NOS Kyu9500 [X]Other and unspecified ovarian cysts Codes for diseases for exclusion -

B Disorders of Autonomic Nervous System

Application of the International Classification of Diseases to Neurology \ Second Edition World Health Organization Geneva 1997 First edition 1987 Second edition 1997 Application of the international classification of diseases to neurology: ICD-NA- 2nd ed. 1. Neurology - classification 2. Nervous system diseases - classification I. Title: ICD-NA ISBN 92 4 154502 X (NLM Classification: WL 15) The World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. Applications and enquiries should be addressed to the Office of Publications, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, which will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. ©World Health Organization 1997 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of -

“The Study of Incidence and Patterns of Adrenal Haemorrhage in All Death Cases”

“THE STUDY OF INCIDENCE AND PATTERNS OF ADRENAL HAEMORRHAGE IN ALL DEATH CASES” Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of The requirements for the degree M.D. (Forensic Medicine) BRANCH- XV INSTITUTE OF FORENSIC MEDICINE MADRAS MEDICAL COLLEGE CHENNAI – 600003 THE TAMILNADU Dr. M.G.R. MEDICAL UNIVERSITY CHENNAI 2015 - 2018 BONAFIDE CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the work embodied in this dissertation entitled “THE STUDY OF INCIDENCE AND PATTERNS OF ADRENAL HAEMORRHAGE IN ALL DEATH CASES” has been carried out by Dr. G. AMRITHA SULTHANA, M.B.B.S, a Post Graduate student under my supervision and guidance for her study leading to Branch XV M. D. Degree in Forensic Medicine during the period of May-2015 to May-2018. Prof. Dr. R. Narayana Babu M.D., Prof. Dr. P. Parasakthi M.D., DEAN DIRECTOR AND PROFESSOR Madras Medical College & Institute of Forensic Medicine Rajiv Gandhi Govt. General Madras Medical College Hospital Chennai-3 Chennai-3 Date: Place: DECLARATION I, Dr. G. AMRITHA SULTHANA, solemnly declare that this dissertation entitled “THE STUDY OF INCIDENCE AND PATTERNS OF ADRENAL HAEMORRHAGE IN ALL DEATH CASES” is the bonafide work done by me under the expert guidance and supervision of Dr.P.Parasakthi, M.D., Professor and Director, Institute of Forensic Medicine, Madras Medical College, Chennai–3.This dissertation is submitted to the Tamil Nadu Dr.M.G.R Medical University towards partial fulfilment of requirement for the award of M.D., Degree (Branch XV) in Forensic Medicine. Place: Dr. G.AMRITHA SULTHANA Date: ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am greatly obliged to the Dean, Dr. -

Management of Adrenal Insufficiency Risk After Long-Term Systemic

Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 6 (2019) 31–41 31 DOI 10.3233/JND-180346 IOS Press Review Management of Adrenal Insufficiency Risk After Long-term Systemic Glucocorticoid Therapy in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Clinical Practice Recommendations Sasigarn A. Bowdena,∗, Anne M. Connollyb, Kathi Kinnettc and Philip S. Zeitlerd aDivision of Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital/The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA bDepartment of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA cParent Project Muscular Dystrophy, Hackensack, New Jersey, USA dDepartment of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA Abstract. Long-term glucocorticoid therapy has improved outcomes in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. However, the recommended glucocorticoid dosage suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to adrenal insufficiency that may develop during severe illness, trauma or surgery, and after discontinuation of glucocorticoid therapy. The purpose of this review is to highlight the risk of adrenal insufficiency in this patient population, and provide practical recommendations for management of adrenal insufficiency, glucocorticoid withdrawal, and adrenal function testing. Strategies to increase awareness among patients, families, and health care providers are also discussed. Keywords: Muscular dystrophy, adrenal crisis, adrenal suppression, cortisol, prednisone, deflazacort, ACTH INTRODUCTION male newborns [2–5]. Therapy with glucocorticoids (GC) improves muscle strength, prolongs ambula- Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an tion and maintains cardiac muscle and pulmonary X-linked recessive neuromuscular disease, character- function [6, 7]. Nevertheless, prolonged use of ized by progressive muscle weakness, with eventual daily GC therapy is associated with significant side loss of ambulation and premature death [1]. -

Leonard G. Gomella.Pdf

Unknown SECOND EDITION THE 5-MINUTE UROLOGY CONSULT Editor-in-Chief Leonard G. Gomella, MD, FACS The Bernard W. Godwin, Jr. Professor of Prostate Cancer Chairman Department of Urology Jefferson Medical College and Associate Director, Kimmel Cancer Center Thomas Jefferson University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Associate Editors Gerald L. Andriole, MD, FACS Arthur L. Burnett, MD, FACS Anthony J. Casale, MD, FAAP, FACS Robert C. Flanigan, MD, FACS Thomas E. Keane, MBBCh, FRCSI, FACS Judd W. Moul, MD, FACS Raju Thomas, MD, MHA, FACS Acquisitions Editor: Brian Brown Product Manager: Ryan Shaw/Erika Kors Manufacturing Manager: Benjamin Rivera Marketing Manager: Lisa Lawrence Design Coordinator: Terry Mallon Production Services: Aptara, Inc. 2nd Edition © 2010 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business 530 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 LWW.com All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be repro- duced in any form or by any means, including photocopying, or utilizing by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The 5-minute urology consult / [edited by] Leonard G. Gomella.—2nd ed. p.; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58255-722-9 1. Urology—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Urinary organs—Diseases—Handbooks, manu- als, etc. I. Gomella, Leonard G. II. Title: Five minute urology consult. [DNLM: 1. Urologic Diseases—Handbooks. WJ 39 Z999 2009] RC872.9.A14 2009 616.6–dc22 2009033129 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. -

Alice C. Levine Editor Physiology, Pathophysiology and Treatment

Contemporary Endocrinology Series Editor: Leonid Poretsky Alice C. Levine Editor Adrenal Disorders Physiology, Pathophysiology and Treatment Contemporary Endocrinology Series Editor Leonid Poretsky Division of Endocrinology Lenox Hill Hospital New York, New York USA More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7680 Alice C. Levine Editor Adrenal Disorders Physiology, Pathophysiology and Treatment Editor Alice C. Levine Div of Endocrinology and Bone Diseases Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai New York, New York USA Contemporary Endocrinology ISBN 978-3-319-62469-3 ISBN 978-3-319-62470-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-62470-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017955781 © Springer International Publishing AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Serum Steroid Profiling by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass

H OH metabolites OH Case Report Serum Steroid Profiling by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry for the Rapid Confirmation and Early Treatment of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Neonatal Case Report Ilaria Cicalini 1,2 , Stefano Tumini 3, Paola Irma Guidone 4, Damiana Pieragostino 1,5, Mirco Zucchelli 1,5, Sara Franchi 1,6, Gabriele Lisi 2,7, Pierluigi Lelli Chiesa 2,7, Liborio Stuppia 1,6, Vincenzo De Laurenzi 1,5 and Claudia Rossi 1,2,* 1 Center for Advanced Studies and Technology (CAST), University “G. d’Annunzio” of Chieti-Pescara, 66100 Chieti, Italy; [email protected] (I.C.); [email protected] (D.P.); [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (V.D.L.) 2 Department of Medicine and Aging Science, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, 66013 Chieti, Italy; [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (P.L.C.) 3 Department of Pediatrics, “G. d’Annunzio” University, 66100 Chieti, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Pediatrics, “Ospedale della Murgia—Fabio Perinei ”, 70022 Altamura, Italy; [email protected] 5 Department of Medical, Oral and Biotechnological Sciences, University “G. d’Annunzio” of Chieti-Pescara, 66100 Chieti, Italy 6 Department of Psychological, Healthand Territory Sciences, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, “G. d’Annunzio” University, 66100 Chieti, Italy 7 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Pescara Hospital, 65124 Pescara, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 3 October 2019; Accepted: 19 November 2019; Published: 21 November 2019 Abstract: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) describes a group of autosomal recessive disorders of steroid biosynthesis, in 95% of cases due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. -

Endocrine Disorders of Pineal, Thyroid, Parathyroid, Pancreas, Adrenal, and Reproductive Glands

Endocrine Disorders of Pineal, Thyroid, Parathyroid, Pancreas, Adrenal, and Reproductive Glands Dr. Amit Ranjan, Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology MGCUB, Motihari, Bihar Pineal Gland ( also known as the Third Eye) Pineal gland --- pinecone shaped Mass -- 0.1 to 0.2 g It is attached to the roof of the 3rd ventricle of the brain It is covered by a capsule formed by the pia mater The gland consists of masses of neuroglea and secretory cell Called pinealocyte. Pinealocyte or neuroglea secretes Melatonin (derivative of serotonin). Secretion of melatonin is regulated by SCN (supra chiasmatic nulceus). SCN set the biological clock of the body. Light and dark----acts on SCN and SCN stimulates sympathetic post ganglionic neuron of the superior cervical ganglion (SCG). SCG stimulates pineal gland (pinealocyte) and secretes melatonin. In light secretion will be less and in dark secretion will be high. Pineal gland secretes less melatonin during abnormal condition, which may result in: Insomnia abnormal thyroid function anxiety, intestinal hyperactivity Menopause. If more melatonin secretion, it may cause: low blood pressure, Seasonal Affective Disorder, abnormal adrenal functions. Pineal gland dysfunction is disturbance in circadian rhythms. Sleeping too much or little or feeling active or restless in the night due to abnormal pineal gland function. Jet Lag ( Temporary Disorder) When we travel from one time Jet lag, also known as time zone zone to another, e.g. America. change syndrome or At 12:00 in India will be night, desynchronosis, occurs when then at the same time there will people travel rapidly across time be day in America zones or when their sleep is disrupted, for example, because of According to Indian time zone shift work. -

The Unified Medical Language System What Is It and How to Use It?

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology December 4, 2007 The Unified Medical Language System What is it and how to use it? Olivier Bodenreider, MD, PhD Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications Bethesda, Maryland - USA OutlineOutline PartPart I:I: WhatWhat isis thethe UMLS?UMLS? z Introduction z Overview through an example z The three UMLS Knowledge Sources UMLS Metathesaurus UMLS Semantic Network SPECIALIST Lexicon and lexical tools PartPart II:II: HowHow toto useuse thethe UMLS?UMLS? z A UMLS-based algorithm 2 Part I What is the UMLS? (1) Introduction WhatWhat doesdoes UMLSUMLS standstand for?for? UUnifiednified MMedicaledical LLanguageanguage SSystemystem UMLS® Unified Medical Language System® UMLS Metathesaurus® 4 MotivationMotivation StartedStarted inin 19861986 NationalNational LibraryLibrary ofof MedicineMedicine ““LongLong--termterm R&DR&D projectproject”” (Integrated Academic ComplementaryComplementary toto IAIMSIAIMS Information Management Systems) «[…] the UMLS project is an effort to overcome two significant barriers to effective retrieval of machine-readable information. • The first is the variety of ways the same concepts are expressed in different machine-readable sources and by different people. • The second is the distribution of useful information among many disparate databases and systems.» 5 TheThe UMLSUMLS inin practicepractice DatabaseDatabase z Series of relational files InterfacesInterfaces z Web interface: Knowledge Source Server (UMLSKS) z Application programming interfaces