This Thesis Has Been Approved by the Honors Tutorial College and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking U.S. Economic Aid to Egypt

Rethinking U.S. Economic Aid to Egypt Amy Hawthorne OCTOBER 2016 RETHINKING U.S. ECONOMIC AID TO EGYPT Amy Hawthorne OCTOBER 2016 © 2016 Project on Middle East Democracy. All rights reserved. The Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, Washington, D.C. based 501(c)(3) organization. The views represented here do not necessarily reflect the views of POMED, its staff, or its Board members. Limited print copies are also available. Project on Middle East Democracy 1730 Rhode Island Avenue NW, Suite 617 Washington DC 20036 www.pomed.org CONTENTS I. Introduction. 2 II. Background . .4 III. The Bilateral Economic Aid Program: Understanding the Basics. 16 IV. Why Has U.S. Economic Aid Not Had A Greater Positive Impact? . 18 V. The Way Forward . 29 VI. Conclusion . 34 PROJECT ON MIDDLE EAST DEMOCRACY 1 RETHINKING U.S. ECONOMIC AID TO EGYPT I. INTRODUCTION Among the many challenges facing the next U.S. administration in the Middle East will be to forge an effective approach toward Egypt. The years following the 2011 popular uprising that overthrew longtime U.S. ally President Hosni Mubarak have witnessed significant friction with Egypt over issues ranging from democracy and human rights, to how each country defines terrorism (Egypt’s definition encompasses peaceful political activity as well as violent actions), to post-Qaddafi Libya, widening a rift between the two countries that began at least a decade ago. Unless the policies of the current Egyptian government shift, the United States can only seek to manage, not repair, this rift. The next U.S. -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt . Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 . Thematic Headlines Domestic Scene Shafiq and Morsi Trade Barbs Political Parties Still Failing on Constituent Assembly Criteria Egyptian Expatriates Start Voting in Runoff Tahrir Protests Urge Unity against Regime Leftovers 11 Political Powers Call for “Revolutionary Trials” of Regime Remnants Court to Rule in Political Isolation Law within Days Protesters Rescue Girl from Rape in Tahrir Square Beheira March Demands Sacking Prosecutor General Protesters in Port Said Hurl Stones on Security Forces MB Refuses Presidential Council Idea Morsi Campaign Denies American Nationality Claims Shafiq: I Represent the Civil Country Tahrir Square against MB MB Sabotages Shafiq’s Premises during Demonstrations Travel Ban Still Imposed on Adli’s Six Aides Clinton is Ready to “Help” Egypt The Revolution Victims’ Families Consider Resorting to the International Court The Revolution Justice SCAF Discusses the Constituent Assembly with the Advisory Council Shafiq Approves the “Document of the Pledge” In the Aftermath of the Trial Al-Baradei Approves a Presidential Council Day 19 of the Revolution Expatriate Votes The Muslim Brotherhood Rejects the Presidential Council Al-Nour Party’s -

U.S.-Egyptian Relations Since the 2011 Revolution: the Limits of Leverage

U.S.-Egyptian Relations Since the 2011 Revolution: The Limits of Leverage An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Politics in partial fulfillment of the Honors Program by Benjamin Wolkov April 29, 2015 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1. A History of U.S.-Egyptian Relations 7 Chapter 2. Foreign Policy Framework 33 Chapter 3. The Fall of Mubarak, the Rise of the SCAF 53 Chapter 4. Morsi’s Presidency 82 Chapter 5. Relations Under Sisi 115 Conclusion 145 Bibliography 160 1 Introduction Over the past several decades, the United States and Egypt have had a special relationship built around military cooperation and the pursuit of mutual interests in the Middle East. At one point, Egypt was the primary nemesis of American interests in the region as it sought to spread its own form of Arab socialism in cooperation with the Soviet Union. However, since President Anwar Sadat’s decision to sign the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty in 1979, Egypt has proven a bulwark of the United States interests it once opposed. Specifically, those interests are peace with Israel, the continued flow of oil, American control of the region, and stability within the Middle East. In addition to ensuring these interests, the special friendship has given the United States privileges with Egypt, including the use of Egyptian airspace, expedited transit through the Suez Canal for American warships, and the basing of an extraordinary rendition program on Egyptian territory. Noticeably, the United States has developed its relationship with Egypt on military grounds, concentrating on national security rather than issues such as the economy or human rights. -

Rethinking Islamist Politics February 11, 2014 Contents

POMEPS STUDIES 6 islam in a changing middle east Rethinking Islamist Politics February 11, 2014 Contents The Debacle of Orthodox Islamism . 7 Khalil al-Anani, Middle East Institute Understanding the Ideological Drivers Pushing Youth Toward Violence in Post-Coup Egypt . 9 Mokhtar Awad, Center for American Progress Why do Islamists Provide Social Services? . 13 Steven Brooke, University of Texas at Austin Rethinking Post-Islamism and the Study of Changes in Islamist Ideology . 16 By Michaelle Browers, Wake Forest University The Brotherhood Withdraws Into Itself . 19 Nathan J. Brown, George Washington University Were the Islamists Wrong-Footed by the Arab Spring? . 24 François Burgat, CNRS, Institut de recherches et d’études sur le monde arabe et musulman (translated by Patrick Hutchinson) Jihadism: Seven Assumptions Shaken by the Arab Spring . 28 Thomas Hegghammer, Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) The Islamist Appeal to Quranic Authority . 31 Bruce B. Lawrence, Duke University Is the Post-Islamism Thesis Still Valid? . 33 Peter Mandaville, George Mason University Did We Get the Muslim Brotherhood Wrong? . 37 Marc Lynch, George Washington University Rethinking Political Islam? Think Again . 40 Tarek Masoud, Harvard University Islamist Movements and the Political After the Arab Uprisings . 44 Roel Meijer, Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and Ghent University, Belgium Beyond Islamist Groups . 47 Jillian Schwedler, Hunter College, City University of New York The Shifting Legitimization of Democracy and Elections: . 50 Joas Wagemakers, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands Rethinking Islamist Politics . 52 Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, Emory University Progressive Problemshift or Paradigmatic Degeneration? . 56 Stacey Philbrick Yadav, Hobart and William Smith Colleges Online Article Index Please see http://pomeps.org/2014/01/rethinking-islamist-politics-conference/ for online versions of all of the articles in this briefing . -

Egypt Presidential Election Observation Report

EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT JULY 2014 This publication was produced by Democracy International, Inc., for the United States Agency for International Development through Cooperative Agreement No. 3263-A- 13-00002. Photographs in this report were taken by DI while conducting the mission. Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: +1.301.961.1660 www.democracyinternational.com EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT July 2014 Disclaimer This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Democracy International, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................ 4 MAP OF EGYPT .......................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................. II DELEGATION MEMBERS ......................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................... X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 6 ABOUT DI .......................................................... 6 ABOUT THE MISSION ....................................... 7 METHODOLOGY .............................................. 8 BACKGROUND ........................................................ 10 TUMULT -

Fault Lines: Sinai Peninsula 20 OCT 2017 the Sinai Peninsula Is a Complicated Operational Environment (OE)

Fault Lines: Sinai Peninsula 20 OCT 2017 The Sinai Peninsula is a complicated operational environment (OE). At present, there are a number of interconnected conditions creating instability and fostering a favorable environment for the growth of Islamic extremist groups. Egypt is battling this situation with large-scale security operations, yet militant activity is not diminishing. The Egyptian government, in coordination with the Israeli government, is placing renewed interest on countering insurgent actors in the region and establishing a lasting security. Despite its best effort, Egypt has been largely unsuccessful. A variety of factors have contributed to the continued rise of the insurgents. We submit there are four key fault lines contributing to instability. These fault lines are neither mutually exclusive nor are they isolated to the Sinai. In fact, they are inexorably intertwined, in ways between Egypt, Israel, and the Sinai Peninsula. Issues related to faults create stability complications, legitimacy concerns, and disidentification problems that can be easily exploited by interested actors. It is essential to understand the conditions creating the faults, the escalation that results from them operating at the same time, and the potential effects for continued insecurity and ultimately instability in the region. FAULT LINES Egypt-Israel Relations - Enduring geopolitical tension between Egypt and Israel, and complex coordination needs between are “exploitable dissimilar and traditionally untrusting cultures, has potential for explosive effects on regional stability. sources of Political Instability - Continued political instability, generated from leadership turmoil, mounting security concerns, and insufficient efforts for economic development may lead to an exponentially dire security situation and direct and violent instability in the challenges to the government. -

History-Writing and Nation-Building in Nasser's Egypt Mona Arif

Shorofat 1 Constructing the National Past: History-Writing and Nation-Building in Nasser’s Egypt Mona Arif is a scholarly refereed series specialized in humanities and social sciences, Shorofat 1 and issued by the Futuristic Studies Unit, Strategic Studies Program at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Board Chair Mostafa El Feki Editor-in-Chief Khaled Azab Shorofat 1 Editors Omneya El Gamil Aia Radwan Language Revision Perihan Fahmy Graphic Design Mohamed Shaarawy Constructing the National Past History-Writing and Nation-Building in Nasser’s Egypt Mona Arif The views in Shorofat represent the views of the author, not those of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Futuristic Studies Unit Bibliotheca Alexandrina Shorofat 1 Constructing the National Past: History-Writing and Nation-Building in Nasser’s Egypt Bibliotheca Alexandrina Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arif, Mona. Constructing the national past history-writing and nation-building in Nasser’s Egypt / Mona Arif. – Alexandria, Egypt : Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Futuristic Studies Unit, 2017. Pages ; cm. (Shorofat ; 1) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 9782-448-452-977- 1. Nasser, Gamal Abdel, 19182 .1970-. Egypt -- History -- 19521970-. I. Futuristic Studies Unit (Bibliotheca Alexandrina) II. Title. II. Series. 962.053--dc23 2017853316 ISBN: 978-977-452-448-2 Dar El-Kuttub Depository No.: 20671/2017 © 2017 Bibliotheca Alexandrina. All rights reserved. COMMERCIAL REPRODUCTION Reproduction of multiple copies of materials in this publication, in whole or in part, for the purposes of commercial redistribution is prohibited except with written permission from the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. To obtain permission to reproduce materials in this publication for commercial purposes, please contact the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, P.O. Box 138, Chatby 21526, Alexandria, Egypt. -

Daring to Care Reflections on Egypt Before the Revolution and the Way Forward

THE ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS IN EGYPT Daring To Care Reflections on Egypt Before The Revolution And The Way Forward Experts’ Views On The Problems That Have Been Facing Egypt Throughout The First Decade Of The Millennium And Ways To Solve Them Daring to Care i Daring to Care ii Daring to Care Daring to Care Reflections on Egypt before the revolution and the way forward A Publication of the Association of International Civil Servants (AFICS-Egypt) Registered under No.1723/2003 with Ministry of Solidarity iii Daring to Care First published in Egypt in 2011 A Publication of the Association of International Civil Servants (AFICS-Egypt) ILO Cairo Head Office 29, Taha Hussein st. Zamalek, Cairo Registered under No.1723/2003 with Ministry of Solidarity Copyright © AFICS-Egypt All rights reserved Printed in Egypt All articles and essays appearing in this book as appeared in Beyond - Ma’baed publication in English or Arabic between 2002 and 2010. Beyond is the English edition, appeared quarterly as a supplement in Al Ahram Weekly newspaper. Ma’baed magazine is its Arabic edition and was published independently by AFICS-Egypt. BEYOND-MA’BAED is a property of AFICS EGYPT No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission of AFICS Egypt. Printed in Egypt by Moody Graphic International Ltd. 7, Delta st. ,Dokki 12311, Giza, Egypt - www.moodygraphic.com iv Daring to Care To those who have continuously worked at stirring the conscience of Egypt, reminding her of her higher calling and better self. -

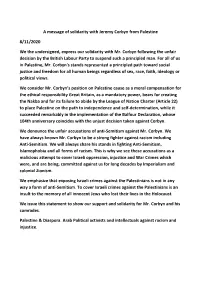

A Message of Solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020

A message of solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020 We the undersigned, express our solidarity with Mr. Corbyn following the unfair decision by the British Labour Party to suspend such a principled man. For all of us in Palestine, Mr. Corbyn's stands represented a principled path toward social justice and freedom for all human beings regardless of sex, race, faith, ideology or political views. We consider Mr. Corbyn’s position on Palestine cause as a moral compensation for the ethical responsibility Great Britain, as a mandatory power, bears for creating the Nakba and for its failure to abide by the League of Nation Charter (Article 22) to place Palestine on the path to independence and self-determination, while it succeeded remarkably in the implementation of the Balfour Declaration, whose 104th anniversary coincides with the unjust decision taken against Corbyn. We denounce the unfair accusations of anti-Semitism against Mr. Corbyn. We have always known Mr. Corbyn to be a strong fighter against racism including Anti-Semitism. We will always share his stands in fighting Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and all forms of racism. This is why we see these accusations as a malicious attempt to cover Israeli oppression, injustice and War Crimes which were, and are being, committed against us for long decades by Imperialism and colonial Zionism. We emphasize that exposing Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is not in any way a form of anti-Semitism. To cover Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is an insult to the memory of all innocent Jews who lost their lives in the Holocaust. -

El-Beblawi Meets Party Heads

AILY EWS MONDAY, AUGUST 5, 2013 N D ISSUE NO. 2249 NEWSTAND PRICE LE 4.00 EGYPT www.thedailynewsegypt.com Egypt’s Only Daily Independent Newspaper In English MEDIA WAR NO FLY ZONE VEG OUT Arrests follow Media City clashes EgyptAir is waiting for cabinet Veggie Fest provides music with a near 6 October approval to built Aero City vegetarian iftar 2 7 8 El-Beblawi meets party heads Hassan Mustafa AL-NOUR PARTY CONDEMNS MEETING released Court orders the release of Alexandrian political activist By Basil El-Dabh Adaweya and Nahda Square. the government and the release of method that lacks transparency,” The parties also discussed “bad political detainees as part of tran- said Taha in a statement in response after six months in jail Interim Prime Minister Hazem El- financial conditions with regards to sitional justice and an “economic to the absence of Islamist parties Beblawi met party heads and lead- economic and social justice,” ac- package to meet the urgent needs in the meeting. He condemned the ers of the National Salvation Front cording to Aboul Ghar. of citizens.” government’s “dealing with political on Saturday evening to discuss the Founder of Al-Tayar Al-Shaaby Topics including security issues parties according to political and ongoing political crisis. and former presidential candidate in Sinai, social and economic initia- ideological vision,” warning that Chairman of the Egyptian Social Hamdeen Sabahy recommended a tives, and upcoming parliamentary such practices would lead to more Democratic Party Mohamed Aboul “security blockade” around the sit- and presidential elections were dis- polarisation and tension in the Ghar said the politicians discussed ins at Rabaa Al-Adaweya and Nahda cussed during the meeting. -

Playing with Fire. the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian

Playing with Fire.The Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian Leviathan Daniela Pioppi After the fall of Mubarak, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) decided to act as a stabilising force, to abandon the street and to lend democratic legiti- macy to the political process designed by the army. The outcome of this strategy was that the MB was first ‘burned’ politically and then harshly repressed after having exhausted its stabilising role. The main mistakes the Brothers made were, first, to turn their back on several opportunities to spearhead the revolt by leading popular forces and, second, to keep their strategy for change gradualist and conservative, seeking compromises with parts of the former regime even though the turmoil and expectations in the country required a much bolder strategy. Keywords: Egypt, Muslim Brotherhood, Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Arab Spring This article aims to analyse and evaluate the post-Mubarak politics of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in an attempt to explain its swift political parable from the heights of power to one of the worst waves of repression in the movement’s history. In order to do so, the analysis will start with the period before the ‘25th of January Revolution’. This is because current events cannot be correctly under- stood without moving beyond formal politics to the structural evolution of the Egyptian system of power before and after the 2011 uprising. In the second and third parts of this article, Egypt’s still unfinished ‘post-revolutionary’ political tran- sition is then examined. It is divided into two parts: 1) the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF)-led phase from February 2011 up to the presidential elections in summer 2012; and 2) the MB-led phase that ended with the military takeover in July 2013 and the ensuing violent crackdown on the Brotherhood. -

Parliament Special Edition

October 2016 22nd Issue Special Edition Our Continent Africa is a periodical on the current 150 Years of Egypt’s Parliament political, economic, and cultural developments in Africa issued by In this issue ................................................... 1 Foreign Information Sector, State Information Service. Editorial by H. E. Ambassador Salah A. Elsadek, Chair- man of State Information Service .................... 2-3 Chairman Salah A. Elsadek Constitutional and Parliamentary Life in Egypt By Mohamed Anwar and Sherine Maher Editor-in-Chief Abd El-Moaty Abouzed History of Egyptian Constitutions .................. 4 Parliamentary Speakers since Inception till Deputy Editor-in-Chief Fatima El-Zahraa Mohamed Ali Current .......................................................... 11 Speaker of the House of Representatives Managing Editor Mohamed Ghreeb (Documentary Profile) ................................... 15 Pan-African Parliament By Mohamed Anwar Deputy Managing Editor Mohamed Anwar and Shaima Atwa Pan-African Parliament (PAP) Supporting As- Translation & Editing Nashwa Abdel Hamid pirations and Ambitions of African Nations 18 Layout Profile of Former Presidents of Pan-African Gamal Mahmoud Ali Parliament ...................................................... 27 Current PAP President Roger Nkodo Dang, a We make every effort to keep our Closer Look .................................................... 31 pages current and informative. Please let us know of any Women in Egyptian and African Parliaments, comments and suggestions you an endless march of accomplishments .......... 32 have for improving our magazine. [email protected] Editorial This special issue of “Our Continent Africa” Magazine coincides with Egypt’s celebrations marking the inception of parliamentary life 150 years ago (1688-2016) including numerous func- tions atop of which come the convening of ses- sions of both the Pan-African Parliament and the Arab Parliament in the infamous city of Sharm el-Sheikh.