AN ANALYTICAL STUDY of a STRING AROUND AUTUMN by TORU TAKEMITSU by Tze-Ying Wu Submitted to the Faculty of the Jacobs School Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

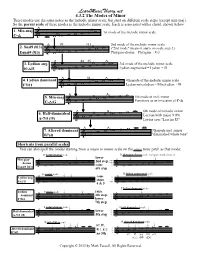

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 89, 1969-1970

THE SOLOISTS KINSHI TSURUTA, born in Ebeotsu Asahi- kawa in the Hokkaido Prefecture, is a player of the traditional Japanese instru- ment, the biwa. In November 1961 she appeared on stage for the first time since World War II in a joint recital. On film she has been heard in the music of Takemitsu for Kwaidan. She and Katsuya Yokoyama created the music for a series of television dramas, Yoshitsune, broadcast by NHK. photo by Dick Loek Takemitsu wrote a new work for Kinshi Tsuruta and Mr Yokoyama called Eclipse, played at the Nissei Theater in May 1966. KATSUYA YOKOYAMA, a leading player of the shakuhachi, was born in Kohnuki Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture. He is known for his interpretation of almost all the new music written for his instrument in Japan. He is also a member of 'Sanbonkai', a trio of Japanese instrumentalists. His playing has been heard in the film scores by Take- mitsu for Seppuku and Kwaidan as well as in the television series Yoshitsune. His tra- SM^^^^M^^^^*. JJ. photo by Dick Loek ditional instrument is a bamboo flute, and his technique has been inherited from his teacher, Watazumi. Both Kinshi Tsuruta and Katsuya Yokoyama have taken part in the recording of November steps no. 1 with the Toronto Symphony, conducted by Seiji Ozawa, for RCA. EVELYN MANDAC, born in the Philippines, took her degree in music at the University of the Philippines. She then studied for several years at Oberlin College and the Juilliard School of Music. Last season she appeared with the Orchestras of Honolulu and Phoenix, with the Oratorio Society of New York and the Dallas and San Antonio Symphonies. -

Joe's Guitar Method Towards a Jazz Improviser's Technique

Joe’s Guitar Method Towards A Jazz Improviser’s Technique I. Intro Pg. 1 II. Tuning & Setup Pg. 5 A. The Grand Staff B. Using a Tuner C. Intonation D. Action and String Gauges E. About Whammy Bars III. Learning The Fretboard Pg. 11 A. The C Major Scale....(how to find the “natural” pitches on each string) IV. Basic Guitar Techniques Pg. 13 A. Overview B. Holding the Pick C. Fretting Hand: Placement of the Fingers D. String Dampening E. Fretting Hand: Placement Of the Thumb F. Fretting Hand: Finger Stretches G. Fretting Hand: The Wrist (About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome) H. Position Playing on Single Strings V. Single String Exercises Pg. 19 A. 6th String B. 5th String C. 4th String D. 3rd String E. 2nd String F. 1st String G. Phrasing Possibilities On A Single String VI. Chords: Construction/Execution/Basic Harmony Pg. 35 A. Triads 1. Construction 2. Movable Triadic Chord Forms a) Freddie Green Style - Part 1 (1) Strumming (2) Pressure Release Points (3) Rhythm Slashes (4) Changing Chords 3. Inversions 4. Open Position Major Chord Forms 5. Open Position - Other Triadic Chords a) Palm Mutes B. Seventh Chords 1. Construction 2. Movable Seventh Chord Forms 3. Open Position Seventh Chord Forms C. Chords With Added Tensions 1. Construction D. Simple Diatonic Harmony E. Elementary Voice Leading F. Changes To Some Standard Tunes 1. All The Things You Are 2. Confirmation 3. Rhythm Changes 4. Sweet Georgia Brown 5. All Of Me 5. All Of Me VII. Open Position Pg. 69 A. Overview B. Picking Techniques 1. -

A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2016 A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum Alexis Joy Smerdon University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Music Education Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Smerdon, Alexis Joy, "A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4076 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Alexis Joy Smerdon entitled "A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Barbara A. Murphy, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Kenneth Stephenson, Alex van Duuren Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Alexis Joy Smerdon August 2016 ii Copyright © 2016 by Alexis Joy Smerdon All rights reserved. -

Toru Takemitsu Compositor Transversal Osesp 2015

MINISTÉRIO DA CULTURA, GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO E SECRETARIA DA CULTURA APRESENTAM TORU TAKEMITSU COMPOSITOR TRANSVERSAL OSESP 2015 O MAGO DOS SILÊNCIOS, POR JO TAKAHASHI 2 CRONOLOGIA 6 OBRAS DE TAKEMITSU NA TEMPORADA 2015 DA OSESP 8 GRAVAÇÕES RECOMENDADAS 12 PRINCIPAIS OBRAS 14 DoIS TEXTOS DE TAKEMITSU 16 2 O MAGO DoS SPOR ILJO ETAKAHASHINCIOS 3 SUGESTÕES DE LEITURA m dos aspectos que tornam a cultura japo- nesa tão hermética — e fascinante — para os ocidentais é o culto ao vazio, revelado Peter Burt especialmente nas artes tradicionais e no THE MUSIC OF TORU TAKEMITSU Uzen-budismo. Na arquitetura clássica e nos jardins, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2001 os espaços vazios criam tensões que tornam o diá- logo entre dois eixos mais dinâmicos. Nas gravuras Toru Takemitsu ukiyo-e, esses vazios potencializam expectativas CONFRONTING SILENCE: contidas, como a espera por uma chuva que tarda a SELECTED WRITINGS cair. O fato é que o vazio, na cultura japonesa, não SCARECROW, 1995 significa ausência. Pelo contrário, trata-se de um espaço intervalar de grande potência expressiva, Francisco F. Feliciano que extrapola molduras e atinge os sentidos mais FOUR ASIAN CONTEMPORARY COMPOSERS: THE INFLUENCE subliminares. Esse vazio não é estático, mas um OF TRADITION IN THEIR WORKS elemento de inflexão que prepara para um próximo NEW DAY, 1983 salto — um momento em suspensão dramática. Toru Takemitsu (1930-96) soube extrair a po- Alain Poirier tencialidade do vazio e inseri-la na linguagem da TORU TAKEMITSU música contemporânea, sobretudo na forma do MICHEL DE MAULE, 1996 silêncio, que, para ele, era tão importante quanto qualquer nota musical. -

Towards a Generative Framework for Understanding Musical Modes

Table of Contents Introduction & Key Terms................................................................................1 Chapter I. Heptatonic Modes.............................................................................3 Section 1.1: The Church Mode Set..............................................................3 Section 1.2: The Melodic Minor Mode Set...................................................10 Section 1.3: The Neapolitan Mode Set........................................................16 Section 1.4: The Harmonic Major and Minor Mode Sets...................................21 Section 1.5: The Harmonic Lydian, Harmonic Phrygian, and Double Harmonic Mode Sets..................................................................26 Chapter II. Pentatonic Modes..........................................................................29 Section 2.1: The Pentatonic Church Mode Set...............................................29 Section 2.2: The Pentatonic Melodic Minor Mode Set......................................34 Chapter III. Rhythmic Modes..........................................................................40 Section 3.1: Rhythmic Modes in a Twelve-Beat Cycle.....................................40 Section 3.2: Rhythmic Modes in a Sixteen-Beat Cycle.....................................41 Applications of the Generative Modal Framework..................................................45 Bibliography.............................................................................................46 O1 O Introduction Western -

Piano Scales

HAMSA MUSIC INSTITUTE #896/1/3, 1STST FLOOR, 1 ‘A’ MHIN ROAD, MAHALAKSHMI LAYOUT ENTUANCE MAHALASHMIPURAM, BANGALORE-86. Mob:9945169825. www.hamsamusic.wordpress.com [email protected] PIANO SCALES Name…………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………... C D E F G A B C Major Scale intervals: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 half-steps: 2-2-1-2-2-2-1 notes: C,D,E,F,G,A,B Eb Ab C D F G B C Harmonic Minor Scale intervals: 1,2,b3,4,5,b6,7 half-steps: 2-1-2-2-1-3-1 notes: C,D,Eb,F,G,Ab,B Eb C D F G A B C Melodic Minor (Ascending) Scale intervals: 1,2,b3,4,5,6,7 half-steps: 2-1-2-2-2-2-1 notes: C,D,Eb,F,G,A,B Eb Ab Bb C D F G C Melodic Minor (Descending) Scale a.k.a.: C Natural Minor, C Relative Minor intervals: 1,2,b3,4,5,b6,b7 half-steps: 2-1-2-2-1-2-2 notes: C,D,Eb,F,G,Ab,Bb F# G# Bb C D E C Whole Tone Scale intervals: 1,2,3,#4,#5,b7 half-steps: 2-2-2-2-2-2 notes: C,D,E,F#,G#,Bb C D E G A C Pentatonic Major Scale intervals: 1,2,3,5,6 half-steps: 2-2-3-2-3 notes: C,D,E,G,A Eb Bb C F G C Pentatonic Minor Scale intervals: 1,b3,4,5,b7 half-steps: 3-2-2-3-2 notes: C,Eb,F,G,Bb Eb Gb Bb C F G C Pentatonic Blues Scale intervals: 1,b3,4,b5,5,b7 half-steps: 3-2-1-1-3-2 notes: C,Eb,F,Gb,G,Bb Bb C D F G C Pentatonic Neutral Scale intervals: 1,2,4,5,b7 half-steps: 2-3-2-3-2 notes: C,D,F,G,Bb Db Eb Gb Bb C E G A C Octatonic (H-W) Scale intervals: 1,b2,b3,3,b5,5,6,b7 half-steps: 1-2-1-2-1-2-1-2 notes: C,Db,Eb,E,Gb,G,A,Bb Eb Gb Ab C D F A B C Octatonic (W-H) Scale intervals: 1,2,b3,4,b5,b6,6,7 -

Music Theory Contents

Music theory Contents 1 Music theory 1 1.1 History of music theory ........................................ 1 1.2 Fundamentals of music ........................................ 3 1.2.1 Pitch ............................................. 3 1.2.2 Scales and modes ....................................... 4 1.2.3 Consonance and dissonance .................................. 4 1.2.4 Rhythm ............................................ 5 1.2.5 Chord ............................................. 5 1.2.6 Melody ............................................ 5 1.2.7 Harmony ........................................... 6 1.2.8 Texture ............................................ 6 1.2.9 Timbre ............................................ 6 1.2.10 Expression .......................................... 7 1.2.11 Form or structure ....................................... 7 1.2.12 Performance and style ..................................... 8 1.2.13 Music perception and cognition ................................ 8 1.2.14 Serial composition and set theory ............................... 8 1.2.15 Musical semiotics ....................................... 8 1.3 Music subjects ............................................. 8 1.3.1 Notation ............................................ 8 1.3.2 Mathematics ......................................... 8 1.3.3 Analysis ............................................ 9 1.3.4 Ear training .......................................... 9 1.4 See also ................................................ 9 1.5 Notes ................................................ -

Toru Takemitsu” Held in Tokyo (August)

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 T#ru Takemitsu: The Roots of His Creation Haruyo Sakamoto Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLOR IDA STATE UN IV ERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC TRU TAKEMITSU: THE ROOTS OF HIS CREATION By HARUYO SAKAMOTO A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Haruyo Sakamoto defended on December 10, 2002. __________________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Victoria McArthur Outside Committee Member __________________________________ Carolyn Bridger Committee Member __________________________________ James Streem Committee Member Approved: _______________________________________________________________________ Seth Beckman, Assistant Dean, School of Music The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above-named committee members. In memory of my mother whose love and support made it possible for me to complete my studies With all my love and appreciation iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deepest appreciation to Professor Leonard Mastrogiacomo for his encouragement, support, and insightful advice for the completion of this treatise. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Carolyn Bridger, Dr. Victoria McArthur, and Professor James Streem for their generous help, cooperation, and guidance. Dr. and Mrs. Stephen Van Camerik have been kind enough to offer assistance as editors. Lastly, but not least, I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my family and friends, who stood by me with love and understanding. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 104, 1984-1985

Boston Symphony Orchestra SEIJI OZAWA, Music Director ^BOSTON \ SYMPHONY I J \ ORCHESTRA/ JV, SEIJI OZAWA A 104th Season \\ M Music Dinctor X 1 1984-85 sags SHARE THE SENSE OF /Qfcf 'ti REMY MARTIN COGNAC EXCLUSIVELY FINE CHAMPAGNE COGNAC. Imported ByRemy Martin Amerique. Inc.. NY, N.Y 80 Proof Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Fourth Season, 1984-85 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Leo L. Beranek, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President J.P. Barger, lice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Mrs. George L. Sargent, Vice-President William J. Poorvu, Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Michael H. Davis David G. Mugar David B. Arnold, Jr. Archie C. Epps Thomas D. Perry, Jr. Mrs. John M. Bradley Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick William J. Poorvu Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Mrs. John L. Grandin Irving W Rabb George H.A. Clowes, Jr. Harvey Chet Krentzman Mrs. George R. Rowland William M. Crozier, Jr. Roderick M. MacDougall Richard A. Smith Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney E. James Morton John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. John T. Noonan Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Mrs. James H. Perkins Richard R Chapman Edward G. Murray Paul C. Reardon Abram T. Collier Albert L. Nickerson Sidney Stoneman Mrs. Harris Fahnestock John L. Thorndike Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thomas W. Morris, General Manager William Bernell, Artistic Administrator Daniel R. Gustin, Assistant Manager Anne H. Parsons, Orchestra Manager Caroline Smedvig, Director ofPromotion Josiah Stevenson, Director ofDevelopment Theodore A. Vlahos, Director ofBusiness Affairs Charles S. Fox, Director ofAnnual Giving Richard Ortner, Administrator of Arlene Germain, Financial Analyst Tanglewood Music Center Charles Gilroy, ChiefAccountant Robert A. -

The Lydian Chromatic Concept

The Lydian Chromatic Concept -For Guitar- -by Pebber Brown Lydian Chromatic Scale for Guitar CopyLeft © 2009 • by Pebber Brown • www.pbguitarstudio.com Table of Contents Section Title Page 1.00 Aknowledgements 1 2.00 Foreward 2 3.00 Introduction 3 4.00 Major Scale Basics 9 5.00 Construction of the Lydian Scale 6.00 Lydian Scale Tonal Gravity Concepts 7.00 The Guitar is Naturally a Lydian Instrument 8.00 Harmonizing the Lydian Scale on the Guitar 9.00 Scale/Chordmode Relationships 10.00 Seven Prinicpal Lydian Chordmodes 11.00 Lydian Scale Chordmode System on Guitar 12.00 Lydian Augmented Scale Guitar Chordmode 13.00 Lydian Diminished Scale Guitar Chordmode 14.00 Lydian b7 Scale Guitar Chordmode 15.00 Auxiliary Augmented Scale (Wholetone) Guitar Chordmode 16.00 Auxiliary Diminished Scale (8-tone Dim) Guitar Chordmode 17.00 Auliliary Dim Blues Scale (8-tone Dom) Guitar Chordmode 18.00 Glossary 19.00 Index 20.00 List of Illustrations LCC for Guitar – Acknowledgements I would like to give thanks to the individuals who inspired me to undertake this work. Thanks for sharing the ideas and opening the window for me. It has opened up some new musical enthusiasm in my life and I every day I ponder more and more tonal possibilities. Special thanks go to: Dr. Reed Gratz – thank you for your infinite patience and wisdom and thank you for creating the course and allowing me to explore this concept in my own way without a fear of a lack of understanding due to academic deadlines. Supreme thanks to the revered Dr. -

Pentatonic Minor Scale

Pentatonic Minor Scale The pentatonic minor guitar scale forms the basis of many famous guitar solos. It is used by practically every lead guitarist in every musical style, and should be among the first guitar scales a beginner guitarist learns. Scale spelling: 1, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭7 1. SAMPLE2. 3. PAGES 4. 5. Guitar Command Guitar Scales Chart Book www.GuitarCommand.com Copyright © 2012 by GuitarCommand.com. All rights reserved. Please report unauthorised distribution to [email protected] 1 Lydian Modal Scale The Lydian is the fourth mode of a major scale. It is the same as a normal major scale but with a raised fourth note, which forms a tritone (augmented fourth interval) with the tonic note and gives the scale its unique sound. Scale spelling: 1, 2, 3, ♯4, 5, 6, 7 1. SAMPLE2. 3. PAGES 4. 5. Guitar Command Guitar Scales Chart Book www.GuitarCommand.com Copyright © 2012 by GuitarCommand.com. All rights reserved. Please report unauthorised distribution to [email protected] 2 Jazz Minor Scale / Melodic Minor Scale The jazz minor scale is also known as the melodic minor scale, although strictly speaking it is only the same as the descending form of the melodic minor used in traditional ‘classical’ music theory. The jazz minor is a good scale to use when improvising over minor sixth chords. If the seventh note of a jazz minor scale is used as the tonic note, it becomes an altered scale. Compare the two scales to see the relationship. Scale spelling: 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, 7 1. SAMPLE2.