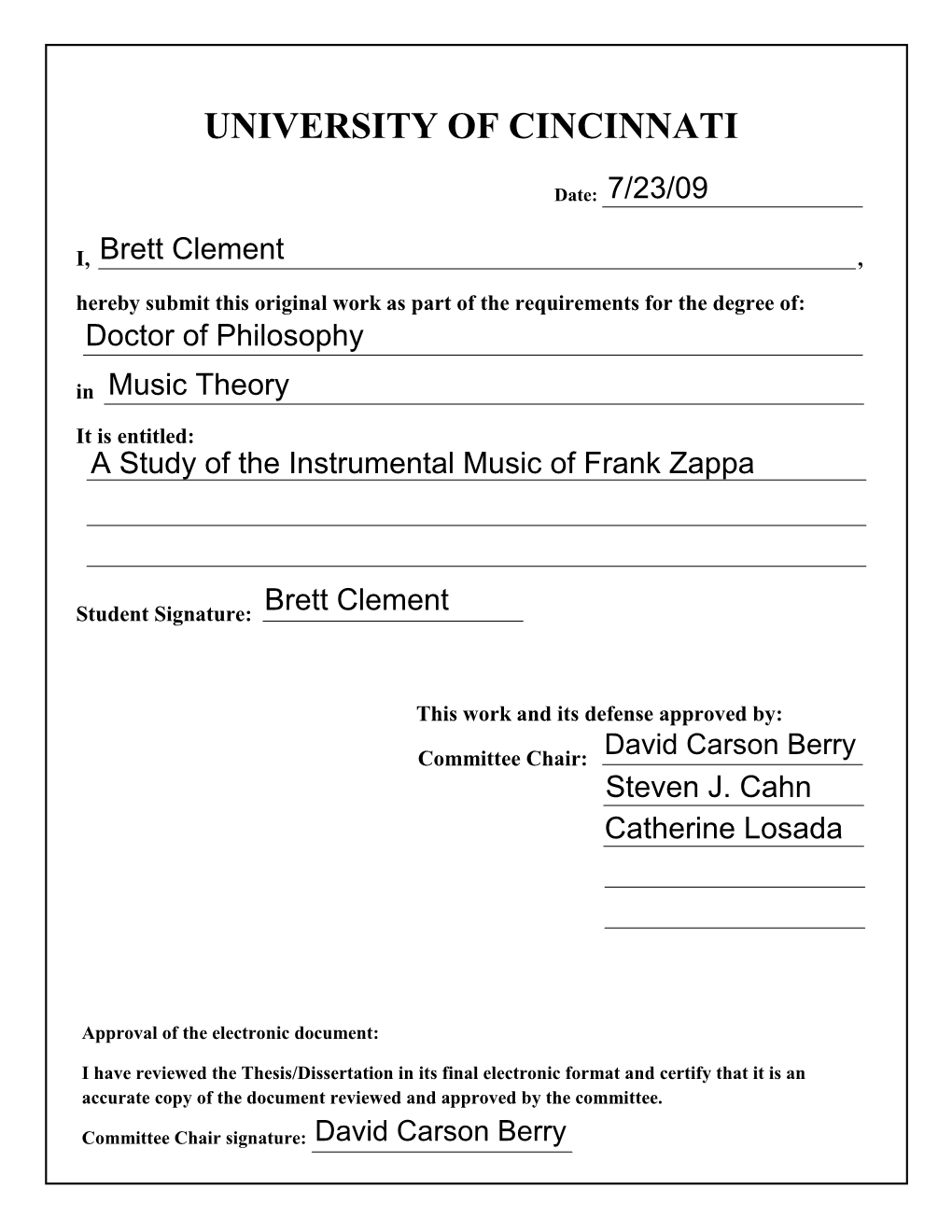

University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gemini Chorus User's Guide

Gemini Chorus User’s Guide Welcome Thank you for purchasing the Gemini Chorus. This powerful stereo effects pedal features a collection of meticulously crafted chorus sounds ranging from classic dual-voice sounds to lush quad-voice ensembles. With a simple control set, the Gemini can work in a wide variety of musical settings, and the powerful MIDI and Neuro control options under the hood provide access to a vast array of additional tonal possibilities. The Gemini is housed in a durable, lightweight aluminum housing, packing rack mount power and flexibility into a compact, easy-to-use stompbox. SA242 Gemini Chorus User’s Guide 1 The USB and Neuro ports transform the Gemini from a simple chorus pedal into a powerful multi- effects unit. Using the free Neuro App (iOS and Android), a wide range of additional control parameters and effect types (phaser, flanger, resonator) are accessible. When used together with the Neuro Hub, the Gemini is fully MIDI-controllable and 128 multi-pedal presets, or “scenes,” can be saved for instant recall on the stage or in the studio. The Gemini can also connect directly to a passive expression pedal or the Hot Hand for expressive control of any parameter. The Quick Start guide will help you with the basics. For more in-depth information about the Gemini Chorus, move on to the following sections, starting with Connections. Enjoy! - The Source Audio Team Overview Diverse Chorus Sounds – Choose from traditional chorus tones such as Dual, Classic, and Quad, or delve deeper into unique sounds cooked up in the Source Audio lab. -

Frank Zappa and His Conception of Civilization Phaze Iii

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2018 FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III Jeffrey Daniel Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.031 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Jeffrey Daniel, "FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 108. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/108 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Metaflanger Table of Contents

MetaFlanger Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Quick Start 3 Flanger effects 5 Chorus effects 5 Producing a phaser effect 5 Chapter 3 More About Flanging 7 Chapter 4 Controls & Displa ys 11 Section 1: Mix, Feedback and Filter controls 11 Section 2: Delay, Rate and Depth controls 14 Section 3: Waveform, Modulation Display and Stereo controls 16 Section 4: Output level 18 Chapter 5 Frequently Asked Questions 19 Chapter 6 Block Diagram 20 Chapter 7.........................................................Tempo Sync in V5.0.............22 MetaFlanger Manual 1 Chapter 1 - Introduction Thanks for buying Waves processors. MetaFlanger is an audio plug-in that can be used to produce a variety of classic tape flanging, vintage phas- er emulation, chorusing, and some unexpected effects. It can emulate traditional analog flangers,fill out a simple sound, create intricate harmonic textures and even generate small rough reverbs and effects. The following pages explain how to use MetaFlanger. MetaFlanger’s Graphic Interface 2 MetaFlanger Manual Chapter 2 - Quick Start For mixing, you can use MetaFlanger as a direct insert and control the amount of flanging with the Mix control. Some applications also offer sends and returns; either way works quite well. 1 When you insert MetaFlanger, it will open with the default settings (click on the Reset button to reload these!). These settings produce a basic classic flanging effect that’s easily tweaked. 2 Preview your audio signal by clicking the Preview button. If you are using a real-time system (such as TDM, VST, or MAS), press ‘play’. You’ll hear the flanged signal. -

Theory Placement Examination (D

SAMPLE Placement Exam for Incoming Grads Name: _______________________ (Compiled by David Bashwiner, University of New Mexico, June 2013) WRITTEN EXAM I. Scales Notate the following scales using accidentals but no key signatures. Write the scale in both ascending and descending forms only if they differ. B major F melodic minor C-sharp harmonic minor II. Key Signatures Notate the following key signatures on both staves. E-flat minor F-sharp major Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) III. Intervals Identify the specific interval between the given pitches (e.g., m2, M2, d5, P5, A5). Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ Note: the sharp is on the A, not the G. Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ IV. Rhythm and Meter Write the following rhythmic series first in 3/4 and then in 6/8. You may have to break larger durations into smaller ones connected by ties. Make sure to use beams and ties to clarify the meter (i.e. divide six-eight bars into two, and divide three-four bars into three). 2 Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) V. Triads and Seventh Chords A. For each of the following sonorities, indicate the root of the chord, its quality, and its figured bass (being sure to include any necessary accidentals in the figures). For quality of chord use the following abbreviations: M=major, m=minor, d=diminished, A=augmented, MM=major-major (major triad with a major seventh), Mm=major-minor, mm=minor-minor, dm=diminished-minor (half-diminished), dd=fully diminished. Root: Quality: Figured Bass: B. -

Allan Holdsworth Schille Reshaping Harmony

BJØRN ALLAN HOLDSWORTH SCHILLE RESHAPING HARMONY Master Thesis in Musicology - February 2011 Institute of Musicology| University of Oslo 3001 2 2 Acknowledgment Writing this master thesis has been an incredible rewarding process, and I would like to use this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to those who have assisted me in my work. Most importantly I would like to thank my wonderful supervisors, Odd Skårberg and Eckhard Baur, for their good advice and guidance. Their continued encouragement and confidence in my work has been a source of strength and motivation throughout these last few years. My thanks to Steve Hunt for his transcription of the chord changes to “Pud Wud” and helpful information regarding his experience of playing with Allan Holdsworth. I also wish to thank Jeremy Poparad for generously providing me with the chord changes to “The Sixteen Men of Tain”. Furthermore I would like to thank Gaute Hellås for his incredible effort of reviewing the text and providing helpful comments where my spelling or formulations was off. His hard work was beyond what any friend could ask for. (I owe you one!) Big thanks to friends and family: Your love, support and patience through the years has always been, and will always be, a source of strength. And finally I wish to acknowledge Arne Torvik for introducing me to the music of Allan Holdsworth so many years ago in a practicing room at the Grieg Academy of Music in Bergen. Looking back, it is obvious that this was one of those life-changing moments; a moment I am sincerely grateful for. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

MTO 20.2: Wild, Vicentino's 31-Tone Compositional Theory

Volume 20, Number 2, June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Genus, Species and Mode in Vicentino’s 31-tone Compositional Theory Jonathan Wild NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.wild.php KEYWORDS: Vicentino, enharmonicism, chromaticism, sixteenth century, tuning, genus, species, mode ABSTRACT: This article explores the pitch structures developed by Nicola Vicentino in his 1555 treatise L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica . I examine the rationale for his background gamut of 31 pitch classes, and document the relationships among his accounts of the genera, species, and modes, and between his and earlier accounts. Specially recorded and retuned audio examples illustrate some of the surviving enharmonic and chromatic musical passages. Received February 2014 Table of Contents Introduction [1] Tuning [4] The Archicembalo [8] Genus [10] Enharmonic division of the whole tone [13] Species [15] Mode [28] Composing in the genera [32] Conclusion [35] Introduction [1] In his treatise of 1555, L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (henceforth L’Antica musica ), the theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino describes a tuning system comprising thirty-one tones to the octave, and presents several excerpts from compositions intended to be sung in that tuning. (1) The rich compositional theory he develops in the treatise, in concert with the few surviving musical passages, offers a tantalizing glimpse of an alternative pathway for musical development, one whose radically augmented pitch materials make possible a vast range of novel melodic gestures and harmonic successions. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

The Music of Frank Zappa MUGC 4890-001 • MUGC 5890-001 Dr

The Music of Frank Zappa MUGC 4890-001 • MUGC 5890-001 Dr. Joseph Klein" III. Social and Cultural Context" Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Post-War Period " Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Family and Lifestyle" Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Cold War & “Red Menace”" Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Cold War & “Red Menace”" Cultural Context — 1950s: B Movies" Cultural Context — 1950s: B Movies" “Zombie Woof”! “Cheepnis”! “The Radio is Broken”! Overnite Sensation ! (1973)! ! Roxy & Elsewhere ! (1974)! The Man From Utopia ! (1983)! Cultural Context — 1960s: Civil Rights Movement" Cultural Context — 1960s: Great Society, Viet Nam War" Cultural Context — 1960s: Hippie Culture & Flower Power" Cultural Context — 1970s: Watergate, Recession" Cultural Context — 1970s: Disco Era" Cultural Context — 1990s: Collapse of the Soviet Union" Archetypes in the Project/Object" § Suzy Creamcheese" §! Hippies" §! Plastic People" §! Pachucos" §! Lonesome Cowboy Burt" §! Bobby Brown" §! Jewish American Princess" §! Catholic Girls" §! Valley Girl" §! Charlie (“kinda young, kinda wow…”)" §! Debbie" §! Thing-Fish (composite archetypes)" “Who Needs the Peace Corps?” (We’re Only In It for the Money, 1968)" I'll stay a week and get the crabs and! Take a bus back home! I'm really just a phony! But forgive me! 'Cause I'm stoned Every town must have a place! Where phony hippies meet! Psychedelic dungeons! Popping up on every street! GO TO SAN FRANCISCO . How I love ya, How I love ya! How I love ya, How I love ya Frisco!! How I love ya, How I love ya! What's there to live for?! How I love ya, How I love ya! Who needs the peace corps?! Oh, my hair is getting good in the back! Think I'll just DROP OUT! Every town must have a place! I'll go to Frisco! Where phony hippies meet! Buy a wig & sleep! Psychedelic dungeons! On Owsley's floor Popping up on every street ! Walked past the wig store! GO TO SAN FRANCISCO . -

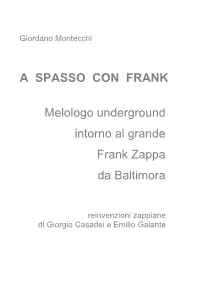

A Spasso Con Frank

Giordano Montecchi A SPASSO CON FRANK Melologo underground intorno al grande Frank Zappa da Baltimora reinvenzioni zappiane di Giorgio Casadei e Emilio Galante 0 [SENZA MUSICA] A Mister Edgard Varèse, 188 Sullivan Street, New York. Agosto 1957 Gentile Signore, forse ricorderà la mia stupida telefonata dello scorso gennaio... Mi chiamo Frank Zappa e ho 16 anni. Le sembrerà strano ma è da quando ho 13 anni che mi interesso alla sua musica. All’epoca l’unica formazione musicale che avevo era qualche rudimento di tecnica del tamburo. Negli ultimi due anni però ho composto alcuni brani musicali utilizzando una rigorosa tecnica dei dodici suoni con risultati che ricordano Anton Webern. Ho scritto due brevi quartetti per fiati e una breve sinfonia per legni ottoni e percussioni. Ultimamente guadagno qualche soldo per mantenermi con la mia blues band, The Blackouts. Dopo il college conto di continuare a comporre e penso mi sarebbero veramente utili i consigli di un veterano come lei. Se mi permettesse di farle visita anche solo per poche ore gliene sarei molto grato. Le sembrerà strano ma penso proprio di avere qualche nuova idea da offrirle in materia di composizione. La prego di rispondermi il più presto possibile perché non resterò a lungo a questo indirizzo. La ringrazio per l’attenzione. Cordiali saluti Frank Zappa Jr. ................... 2 1 PEACHES EN REGALIA [VAMP] I duri del rock lo sentono come loro proprietà esclusiva, come profeta anti- establishment. Gli accademici lo tollerano in quanto compositore... un’eccezione! per il mondo del rock. Chi lo vuole un giullare simbolo della trasgressione più anarcoide..... -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lockett, P.W. (1988). Improvising pianists : aspects of keyboard technique and musical structure in free jazz - 1955-1980. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8259/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] IMPROVISING PIANISTS: ASPECTS OF KEYBOARD TECHNIQUE AND MUSICAL STRUCTURE IN FREE JAll - 1955-1980. Submitted by Mark Peter Wyatt Lockett as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University Department of Music May 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No I List of Figures 3 IIListofRecordings............,........ S III Acknowledgements .. ..... .. .. 9 IV Abstract .. .......... 10 V Text. Chapter 1 .........e.e......... 12 Chapter 2 tee.. see..... S S S 55 Chapter 3 107 Chapter 4 ..................... 161 Chapter 5 ••SS•SSSS....SS•...SS 212 Chapter 6 SS• SSSs•• S•• SS SS S S 249 Chapter 7 eS.S....SS....S...e.