Jazz Improvisation: a Recommended Sequential Format of Instruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COURSE CATALOG 2016-2017 Academic Calendar

COURSE CATALOG 2016-2017 Academic Calendar . 4 Academic Programs . 46 About LACM . .. 6 Performance LACM Educational Programs . 8 Bass . 46 CONTENTS Administration . 10 Brass & Woodwind . .. 52 Admissions . 11 Drums . .. 58 Tuition & Fees . 13 Guitar . 64 Financial Aid . 18 Vocal. 70 Registrar . 22 Music Composition International Student Services . 26 Songwriting . 76 Academic Policies & Procedures . 27 Music Production Student Life . 30 Composing for Visual Media . 82 Career Services . .. 32 Music Producing & Recording . 88 Campus Facilities – Security. 33 Music Industry Rules of Conduct & Expectations . 35 Music Business . 94 Health Policies . 36 Course Descriptions . 100 Grievance Policy & Procedures . .. 39 Department Chairs & Faculty Biographies . 132 Change of Student Status Policies & Procedures . 41 Collegiate Articulation & Transfer Agreements . 44 FALL 2016 (OCTOBER 3 – DECEMBER 16) ACADEMIC DATES SPRING 2017 (APRIL 10 – JUNE 23) ACADEMIC DATES July 25 - 29: Registration Period for October 3 - October 7: Add/Drop January 30 - February 3: Registration Period for April 10 - April 14: Add/Drop Upcoming Quarter Upcoming Quarter October 10 - November 11: Drop with a “W” April 17 - May 19: Drop with a “W” August 22: Tuition Deadline for Continuing Students February 27: Tuition Deadline for November 14 - December 9: Receive a letter grade May 22 - June 16: Receive a letter grade October 3: Quarter Begins Continuing Students November 11: Veterans Day, Campus Closed April 10: Quarter Begins November 24: Thanksgiving, Campus Closed May 29: Memorial Day, Campus Closed November 25: Campus Open, No classes. June 19 - 23: Exams Week December 12-16: Exams Week June 23: Quarter Ends December 16: Quarter Ends December 24 - 25: Christmas, Campus Closed December 26: Campus Open, No classes. -

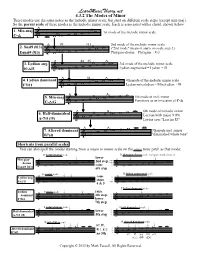

View Printable PDF of 4.2 the Modes of Minor

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.3.2 The Modes of Minor These modes use the same notes as the melodic minor scale, but start on different scale steps (except min-maj). So the parent scale of these modes is the melodic minor scale. Each is associated with a chord, shown below. 1. Min-maj 1st mode of the melodic minor scale C- w wmw ^ & w wmbw w w b9 §13 2nd mode of the melodic minor scale 2. Susb9 (§13) wmw w ("2nd mode" means it starts on scale step 2.) Dsusb9 (§13) & wmbw w w w Phrygian-dorian = Phyrgian + §13 #4 #5 3. Lydian aug. mbw 3rd mode of the melodic minor scale wmw w Lydian augmented = Lydian + #5 Eb ^ #5 & bw w w w #4 4. Lydian dominant 4th mode of the melodic minor scale w wmbw w F7#11 & w w w wm Lydian-mixolydian = Mixolydian + #4 5. Min-maj w w 5th mode of mel. minor wmw wmbw Functions as an inversion of C- C- ^ /G & w w ^ 6th mode of melodic minor 6. Half-diminished w w m w wmbw w Locrian with major 9 (§9) A-7b5 (§9) & w w Levine says "Locrian #2" w 7. Altered dominant wmbw w w w 7th mode mel. minor B7alt & wm w "diminished whole tone" Shortcuts from parallel scales You can also spell the modes starting from a major or minor scale on the same tonic pitch as that mode: D natural minor scale D phrygian-dorian scale (compare marked notes) lower Phrygian- I I 2nd step, I I dorian w bw w w raise _ w nw w w Dsusb9 (§13) & w w w _ & bw w w w 6th step _ w Eb major scale Eb lydian augmented scale Lydian aug. -

The Group-Theoretic Description of Musical Pitch Systems

The Group-theoretic Description of Musical Pitch Systems Marcus Pearce [email protected] 1 Introduction Balzano (1980, 1982, 1986a,b) addresses the question of finding an appropriate level for describing the resources of a pitch system (e.g., the 12-fold or some microtonal division of the octave). His motivation for doing so is twofold: “On the one hand, I am interested as a psychologist who is not overly impressed with the progress we have made since Helmholtz in understanding music perception. On the other hand, I am interested as a computer musician who is trying to find ways of using our pow- erful computational tools to extend the musical [domain] of pitch . ” (Balzano, 1986b, p. 297) Since the resources of a pitch system ultimately depend on the pairwise relations between pitches, the question is one of how to conceive of pitch intervals. In contrast to the prevailing approach which de- scribes intervals in terms of frequency ratios, Balzano presents a description of pitch sets as mathematical groups and describes how the resources of any pitch system may be assessed using this description. Thus he is concerned with presenting an algebraic description of pitch systems as a competitive alternative to the existing acoustic description. In these notes, I shall first give a brief description of the ratio based approach (§2) followed by an equally brief exposition of some necessary concepts from the theory of groups (§3). The following three sections concern the description of the 12-fold division of the octave as a group: §4 presents the nature of the group C12; §5 describes three perceptually relevant properties of pitch-sets in C12; and §6 describes three musically relevant isomorphic representations of C12. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

Jazz Harmony Iii

MU 3323 JAZZ HARMONY III Chord Scales US Army Element, School of Music NAB Little Creek, Norfolk, VA 23521-5170 13 Credit Hours Edition Code 8 Edition Date: March 1988 SUBCOURSE INTRODUCTION This subcourse will enable you to identify and construct chord scales. This subcourse will also enable you to apply chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in harmonic progressions. Unless otherwise stated, the masculine gender of singular is used to refer to both men and women. Prerequisites for this course include: Chapter 2, TC 12-41, Basic Music (Fundamental Notation). A knowledge of key signatures. A knowledge of intervals. A knowledge of chord symbols. A knowledge of chord progressions. NOTE: You can take subcourses MU 1300, Scales and Key Signatures; MU 1305, Intervals and Triads; MU 3320, Jazz Harmony I (Chord Symbols/Extensions); and MU 3322, Jazz Harmony II (Chord Progression) to obtain the prerequisite knowledge to complete this subcourse. You can also read TC 12-42, Harmony to obtain knowledge about traditional chord progression. TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES MU 3323 1 ACTION: You will identify and write scales and modes, identify and write chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in a harmonic progression, and identify and write chord scales that correspond to triads, extended chords and altered chords. CONDITION: Given the information in this subcourse, STANDARD: To demonstrate competency of this task, you must achieve a minimum of 70% on the subcourse examination. MU 3323 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Subcourse Introduction Administrative Instructions Grading and Certification Instructions L esson 1: Sc ales and Modes P art A O verview P art B M ajor and Minor Scales P art C M odal Scales P art D O ther Scales Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 2: R elating Chord Scales to Basic Four Note Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 3: R elating Chord Scales to Triads, Extended Chords, and Altered Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback Examination MU 3323 3 ADMINISTRATIVE INSTRUCTIONS 1. -

Tonical Ambiguity in Three Pieces by Sergei Prokofiev

TONICAL AMBIGUITY IN THREE PIECES BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV by DAVID VINCENT EDWIN STRATKAUSKAS B.Mus.,The University of British Columbia, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (School of Music) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1996 © David Vincent Edwin Stratkauskas, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of MlASlC- The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada •ate OCTDKER II ; • DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT There is much that is traditional in the compositional style of Sergei Prokofiev, invoking the stylistic spirit of the preceding two hundred years. One familiar element is the harmonic vocabulary, as evidenced by the frequent use of simple triadic sonorities, but these seemingly simple sonorities are frequently instilled with a sense of multiple meaning, and help to facilitate a tonal style which differs from the classical norm. In this style, the conditions of monotonality do not necessarily apply; there is often a sense of the coexistence of several "tonical" possibilities. -

An Analysis and Performance Considerations for John

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN (Under the Direction of D. RAY MCCLELLAN) ABSTRACT John Harbison is an award-winning and prolific American composer. He has written for almost every conceivable genre of concert performance with styles ranging from jazz to pre-classical forms. The focus of this study, his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, was premiered in 1985 as a product of a Consortium Commission awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts. The initial discussions for the composition were with oboist Sara Bloom and clarinetist David Shifrin. Harbison’s Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings allows the clarinet to finally be introduced to the concerto grosso texture of the Baroque period, for which it was born too late. This document includes biographical information on John Harbison including his life and career, compositional style, and compositional output. It also contains a brief history of the Baroque concerto grosso and how it relates to the Harbison concerto. There is a detailed set-class analysis of each movement and information on performance considerations. The two performers as well as the composer were interviewed to discuss the commission, premieres, and theoretical/performance considerations for the concerto. INDEX WORDS: John Harbison, Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, Baroque concerto grosso, analysis and performance AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN B.M., Tennessee Technological University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Katherine Belvin All Rights Reserved AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN Major Professor: D. -

A Chord-Scale Approach to Automatic Jazz Improvisation

A CHORD-SCALE APPROACH TO AUTOMATIC JAZZ IMPROVISATION Junqi Deng, Yu-Kwong Kwok Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering The University of Hong Kong fjqdeng,[email protected] ABSTRACT Chord Scale 7 Mixolydian, Phrygian-Dominant, Whole-tone maj7 Lydian, Lydian-Dominant, Ionian, Ionian#5 Jazz improvisation has been one of the biggest challenges min7 Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian in all kinds of musical goals. This late breaking article de- min7b5 Locrian, Locrian#2 scribes a machine to automate this process in a certain de- 7b9 Phrygian-Dominant gree. This machine has three major components: a jazz maj7#11 Lydian maj7#5 Ionian#5 chord estimator, a local scale tracker, and a improvised dim7 Whole-half Diminished melody generator. Simple demo tracks have been gener- ated in terms of chord-melody to showcase the effective- Table 1. Chord-scale choices examples ness and potentials of this system. they learn through extensive practices [4]. To be precise, 1. INTRODUCTION instead of generating notes from the scales, they create Jazz improvisation is considered one of the most difficult phrases that belong to the chord-scale. An infinite number tasks among all kinds of instrumental performances. The of note sequences can be generated out of the chord-scale, difficulty is mainly due to the complex harmonic structure but only some are acceptable to human musical aesthetics. in jazz, the complicated licks and patterns, and the intricate In addition to create phrases within a single harmonic re- musical relationship between these phrases and the har- gion, they also pay attention to the coherence along and monic context. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE a RESOURCE UNIT for the HIGH SCHOOL JAZZ ENSEMBLE a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satisfac

:,. CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE A RESOURCE UNIT FOR THE HIGH SCHOOL JAZZ ENSEMBLE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by James Dale Snodgrass ../ June, 1973 . ;.~ The thesis of James Dale Snodgrass is approved: California State University, Northridge June, 1973 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • X 'CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 The Problem • • • • • • . '. • • • • • • • • 1 Justification for the Study • • • • • • • • 5 Student Motivation • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Professional Training • • • • • • • • • 7 Development of Musicianship • • • • • • 8 Individual Responsibility • • • • • • • 9 Other Unique Advantages to the Jazz Ensemble • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 10 Limitations of this Study • • • • • • • • • -10 Methodology and Sources of Information • • 11 Organization of the Unit • • • • • • • • • 12 II. JAZZ ENSEMBLE IN THE HIGH SCHOOL MUSIC CURRICULUM: ORGANIZATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS 13 Jazz Ensemble as a Part of the Curriculum • 13 Membership Requirements • • • • • • • • 14 l >----·-~--"---~--··· -- .. -·-··-·--- ··- ------ ·---·------·----~---~~---..; iii CHAPTER PAGE Participation in Other Musical Organizations • • • • • • • • • • 14 Academic Requirements • • • • • • .• • 15 Musical Requirements • • • • • • • • 17 Student Leaders • • • • • • • • • • • • 19 Attracting Members • • • • • • • • • • • 22 Scheduling of Class • • • • • • • • • • 25 Financing • • • • • • • • • • • • • • · • -

Joe's Guitar Method Towards a Jazz Improviser's Technique

Joe’s Guitar Method Towards A Jazz Improviser’s Technique I. Intro Pg. 1 II. Tuning & Setup Pg. 5 A. The Grand Staff B. Using a Tuner C. Intonation D. Action and String Gauges E. About Whammy Bars III. Learning The Fretboard Pg. 11 A. The C Major Scale....(how to find the “natural” pitches on each string) IV. Basic Guitar Techniques Pg. 13 A. Overview B. Holding the Pick C. Fretting Hand: Placement of the Fingers D. String Dampening E. Fretting Hand: Placement Of the Thumb F. Fretting Hand: Finger Stretches G. Fretting Hand: The Wrist (About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome) H. Position Playing on Single Strings V. Single String Exercises Pg. 19 A. 6th String B. 5th String C. 4th String D. 3rd String E. 2nd String F. 1st String G. Phrasing Possibilities On A Single String VI. Chords: Construction/Execution/Basic Harmony Pg. 35 A. Triads 1. Construction 2. Movable Triadic Chord Forms a) Freddie Green Style - Part 1 (1) Strumming (2) Pressure Release Points (3) Rhythm Slashes (4) Changing Chords 3. Inversions 4. Open Position Major Chord Forms 5. Open Position - Other Triadic Chords a) Palm Mutes B. Seventh Chords 1. Construction 2. Movable Seventh Chord Forms 3. Open Position Seventh Chord Forms C. Chords With Added Tensions 1. Construction D. Simple Diatonic Harmony E. Elementary Voice Leading F. Changes To Some Standard Tunes 1. All The Things You Are 2. Confirmation 3. Rhythm Changes 4. Sweet Georgia Brown 5. All Of Me 5. All Of Me VII. Open Position Pg. 69 A. Overview B. Picking Techniques 1. -

Jazz at the Crossroads)

MUSIC 127A: 1959 (Jazz at the Crossroads) Professor Anthony Davis Rather than present a chronological account of the development of Jazz, this course will focus on the year 1959 in Jazz, a year of profound change in the music and in our society. In 1959, Jazz is at a crossroads with musicians searching for new directions after the innovations of the late 1940s’ Bebop. Musical figures such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane begin to forge a new direction in music building on their previous success earlier in the fifties. The recording Kind of Blue debuts in 1959 documenting the work of Miles Davis’ legendary sextet with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb and reflects a new direction in the music with the introduction of a modal approach to composition and improvisation. John Coltrane records Giant Steps the culmination of the harmonic intricacies of Bebop and at the same time the beginning of something new. Ornette Coleman arrives in New York and records The Shape of Jazz to Come, an LP that presents a radical departure from the orthodoxies of Be-Bop. Dave Brubeck records Time Out, a record featuring a new approach to rhythmic structure in the music. Charles Mingus records Mingus Ah Um, establishing Mingus as a pre-eminent composer in Jazz. Bill Evans forms his trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian transforming the interaction and function of the rhythm section. The quiet revolution in music reflects a world that is profoundly changed. The movement for Civil Rights has begun. The Birmingham boycott and the Supreme Court decision Brown vs.