THE MONROE DOCTRINE by PAUL MATWYCHUK an Albertan Boy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

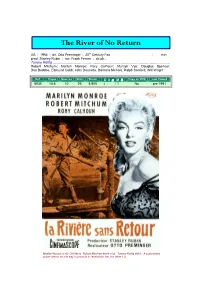

The River of No Return

The River of No Return US : 1954 : dir. Otto Preminger : 20th Century Fox : min prod: Stanley Rubin : scr: Frank Fenton : dir.ph.: Tommy Rettig …..……….……………………………………………………………………………… Robert Mitchum; Marilyn Monroe; Rory Calhoun; Murvyn Vye; Douglas Spencer; Don Beddoe, Edmund Cobb, John Doucette, Barbara Nichols, Ralph Sanford, Will Wright Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω 8 M Copy on VHS Last Viewed 5935 10.5 10 25 5,905 - - No pre 1991 Marilyn Monroe in the Old West. Robert Mitchum drank a lot. Tommy Rettig didn’t. A sepia-tinted poster seems an odd way to promote a Technicolor film, but there it is. People who drink fall over a lot. This is a proven fact. Source: indeterminate Excerpt from The Moving Picture Boy entry Calhoun) and his companion Kay Weston on Nirumand, who starred the previous year in (Monroe). After Calder rescues them from Naderi's “DAWANDEH” (or “The Runner”): the wild river, Weston robs them, and leaves everyone to die. Calder goes after “He kept on running in Naderi's "AAB, him, but is a little puzzled as to why Kay BAAD, KHAK", a drama of drought set in the would remain so loyal to the liar and cheat, parched land of the Iranian-Afghan border. while his son, pulling a “COURTSHIP OF But the Iranian authorities, who had already EDDIE’S FATHER”, tries to get the man castigated "DAWANDEH" as a slur on their and woman together. country, and had failed to get Naderi to The movie is the western equivalent of a apologise for it, now banned the showing of "road film", with Calder and Co. -

2016 Newsletter

Willmore Wilderness Foundation ... a registered charitable foundation 2016 Annual Newsletter Photo by Susan Feddema-Leonard - July 2015 Ali Klassen & Payton Hallock on the top of Mt. Stearn Willmore Wilderness Foundation Page 2 Page 3 Annual Edition - 2016 Jw Mountain Metis otipemisiwak - freemen President’s Report by Bazil Leonard Buy DVDs On LinePeople & Peaks People & Peaks Ancestors Calling Ancestors CallingLong Road Home Long Road Home Centennial Commemoration of Jasper’s Mountain Métis In 1806 Métis guide Jacco Findlay was the first to blaze a packtrail over Howse Pass and the Continental Divide. He made a map for Canadian explorer David Thompson, who followed one year later. Jacco left the North West Company and became one of the first “Freemen” or “Otipemisiwak” in the Athabasca Valley. Long Road Home: 45:13 min - $20.00 In 1907 the Canadian Government passed an Order in Council for the creation of the Ancestors Calling I thought that I would share a campsites, dangerous river fords, and “Jasper Forest Park”—enforcing the evacuation of the Métis in the Athabasca Valley. By 1909 guns were seized causing the community to surrender its homeland--including Jacco’s descendants. Six Métis families made their exodus after inhabiting the area for a century. Ancestors Calling This documentary, In 1804, the North West Company brought voyageurs, proprietors, evicted families, as well as Jacco’s progeny. Stories are shared through the voices of family recap of 2015, which was a year of historic areas on the west side of the members as they revealLong their Road struggle Home to preserve traditions and culture as Mountain Métis. -

The Canadian Rockies!

Canadian Rail & Land Tour – the Canadian Rockies! Vancouver, Rocky Mountaineer- Kamloops-Jasper-Lake Louise-Banff - Calgary August 5-13, 2022 - Journey through the Clouds! $3895.00 per person based on double occupancy. Single Supplement $850.00 Travel Safe Insurance is additional at $259.00 DAY 1 - Flight to Vancouver Arrival and transfer to our hotel. This is a travel day. Overnight – Vancouver – Sutton Place Hotel or similar. DAY 2- Vancouver Tour Spend half a day touring Vancouver’s Natural and urban highlights on this sightseeing bus tour. Visit the key attractions such as Canada Place, Robsen Street, Granville Island, Chinatown and Gastown. Then head to Capilano Suspension Bridge for an exhilarating walk along the cliff- hanging footpaths. Overnight – Vancouver – Breakfast - Dinner Welcome dinner this evening. DAY 3– Rocky Mountaineer - Kamloops Travel onboard Rocky Mountaineer from the coastal city of Vancouver to Kamloops depart at 730am. You will see dramatic changes in scenery, from the lush green fields of the Fraser Valley, through forests and winding river canyons surrounded by the peaks of the Coast and Cascade Mountains, to the desert-like environment of the BC Interior. Highlights include the rushing waters of Hell’s Gate in the Fraser Canyon and the steep slopes and rock sheds along the Thompson River. Overnight in Kamloops arrival 530pm – 700pm. – Lunch - Breakfast DAY 4– Rocky Mountaineer – Kamloops to Jasper Your rail adventure continues at 815am and heads north and east to the mighty Canadian Rockies and the province of Alberta. Highlights include Mount Robson, the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies, Pyramid Falls, and the climb over the Yellowhead Pass into Jasper National Park. -

Salmon River Management Plan, Idaho

Bitterroot, Boise, Nez Perce, Payette, and Salmon-Challis National Forests Record of Decision Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Frank Church – River of No Return Wilderness Revised Wilderness Management Plan and Amendments for Land and Resource Management Plans Bitterroot, Boise, Nez Perce, Payette, and Salmon-Challis NFs Located In: Custer, Idaho, Lemhi, and Valley Counties, Idaho Responsible Agency: USDA - Forest Service Responsible David T. Bull, Forest Supervisor, Bitterroot NF Officials: Bruce E. Bernhardt, Forest Supervisor, Nez Perce NF Mark J. Madrid, Forest Supervisor, Payette NF Lesley W. Thompson, Acting Forest Supervisor, Salmon- Challis NF The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital and family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Person with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. ROD--II Table of Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................... -

Clearwater Defender News of the Big Wild a Publication of Issued Quarterly Friends of the Clearwater Spring 2014, No.1

Clearwater Defender News of the Big Wild A Publication of Issued Quarterly Friends of the Clearwater spring 2014, no.1 Of wolves and wilderness Guest Opinion George Nickas, Wilderness Watch “One of the most insidious invasions of wilderness is via predator control.” – Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac Right before the holidays last December, an anonymous caller alerted Wilderness Watch that the Forest Service (FS) had approved the use of one of its cabins deep in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness (FC- RONRW) as a base camp for an Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) hunter-trapper. The cabin would support the hired trapper’s effort to exterminate two entire wolf packs in the Wilderness. The wolves, known as the Golden Middle Fork Salmon River Creek and Monumental Creek packs, were targeted at the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness behest of commercial outfitters and recreational hunters Rex Parker Photo Credit who think the wolves are eating too many of “their” elk. Idaho’s antipathy toward wolves and Wilderness comes as no surprise to anyone who has worked to pro- Wilderness Act to preserve the area’s wilderness character, tect either in Idaho. But the Forest Service’s support and of which the wolves are an integral part. Trying to limit encouragement for the State’s deplorable actions were the number of wolves in Wilderness makes no more sense particularly disappointing. Mind you, these are the same than limiting the number of ponderosa pine, huckleberry Forest Service Region 4 officials who, only a year or two bushes, rocks, or rainfall. -

Ape Chronicles #035

For a Man! PLANET OF THE APES 1957 The Three Faces of Eve ARMY ARCHERD WHO IS WHO ? 1957 Peyton Place FILMOGRAPHY 1957 No Down Payment 1958 Teacher's Pet (uncredited) FILMOGRAPHY (AtoZ) 1957 Kiss Them for Me 1963 Under the Yum Yum Tree Compiled by Luiz Saulo Adami 1957 A Hatful of Rain 1964 What a Way to Go! (uncredited) http://www.mcanet.com.br/lostinspace/apes/ 1957 Forty Guns 1966 The Oscar (uncredited) apes.html 1957 The Enemy Below 1968 The Young Runaways (uncredited) [email protected] 1957 An Affair to Remember 1968 Planet of the Apes (uncredited) AUTHOR NOTES 1958 The Roots of Heaven 1968 Wild in the Streets Thanks to Alexandre Negrão Paladini, from 1958 Rally' Round the Flag, Boys! 1970 Beneath the Planet of the Apes Brazil; Terry Hoknes, from Canadá; Jeff 1958 The Young Lions (uncredited) Krueger, from United States of America; 1958 The Long, Hot Summer 1971 Escape from the Planet of the Apes and Philip Madden, from England. 1958 Ten North Frederick 1972 Conquest of the Planet of the Apes 1958 The Fly (uncredited) 1959 Woman Obsessed 1973 Battle for the Planet of the Apes To remind a film, an actor or an actress, a 1959 The Man Who Understood Women (uncredited) musical score, an impact image, it is not so 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth/Trip 1974 The Outfit difficult for us, spectators of movies or TV. to the Center of the Earth 1976 Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Really difficult is to remind from where else 1959 The Diary of Anne Frank Hollywood we knew this or that professional. -

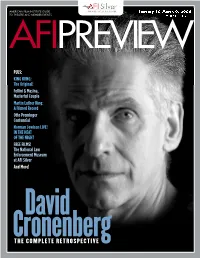

32 • Iissuessue 16 Afipreview

AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE Januaryuary 10–March 9, 2006 TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUMEVOLUME 32 • ISSUEISSUE 61 AFIPREVIEW PLUS: KING KONG: The Original! Fellini & Masina, Masterful Couple Martin Luther King: A Filmed Record Otto Preminger Centennial Norman Jewison LIVE! IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT FREE FILMS! The National Law Enforcement Museum at AFI Silver And More! David CronenbergTHE COMPLETE RETROSPECTIVE NOW PLAYING AWARD NIGHTS AT AFI 2 Oscar® and Grammy® Night Galas! 3 David Cronenberg: The Visceral BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! and the Cerebral ® 6 A True Hollywood Auteur: Otto Preminger Oscar Night 2006! 9 Norman Jewison Presents Sunday, March 5 IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT AFI Silver is proud to host the only Academy®- 9 Martin Luther King Honored sanctioned Oscar Night® party in the Washington area, 9 SILVERDOCS: Save the Date! presented by First Star. On Sunday, March 5, at 6:30 10 About AFI p.m., AFI Silver will be abuzz with red carpet arrivals, 11 Calendar specialty cocktails, a silent auction and a celebrity- 12 Federico Fellini and Giulietta Masina, moderated showing of the Oscar® Awards broadcast— Masterful Pair presented on-screen in high definition! 12 ANA Y LOS OTROS, Presented by Cinema Tropical All proceeds 13 THE FRENCH CONNECTION, SE7EN, and DRAGNET! from this National Law Enforcement Museum’s exclusive event Inaugural Film Festival benefit First 13 Washington, DC, Premiere of Star, a national Terrence Malick’s THE NEW WORLD non-profit 14 One Week Only! CLASSE TOUS RISQUES public charity and SPIRIT OF THE BEEHIVE dedicated to 14 Exclusive Washington Engagement! SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM improving life 15 Montgomery College Film Series for child victims 15 Membership News: It Pays to of abuse and Be an AFI Member! neglect. -

Otto Preminger

Otto Preminger Los ojos y el cerebro Con el tiempo, cualquier gran cineasta –y muchos menores, incluso antes– acaba por ser “descubierto” (o “redescubierto”), y logra una cierta consideración, más o menos extendida y duradera. Ya no se ve como un capricho exótico de una pandilla de chiflados que se admire a Douglas Sirk o Jacques Tourneur, y los nombres de John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock y Howard Hawks han sido finalmente incorporados al Panteón común a críticos y aficionados, de modo que su mera mención se supone elogiosa y no parece necesario defenderlos. Sus causas son batallas libradas y ganadas, e incluso si tal victoria es relativa y sólo afecta a grupos minoritarios, se puede confiar en que, como mucho en un par de generaciones, su posición se habrá consolidado. Mucho más extraña y peor –aunque no para ellos, pues llevan tiempo muertos– es la situación de aquellos que, incluso si durante algún periodo –usualmente de cinco a diez años– tuvieron éxito comercial, ganaron algún premio y alcanzaron cierta aceptación crítica, cayeron después en desgracia y en el olvido, y cuya reputación ha permanecido largamente estancada a un nivel muy inferior al que merecen, sobre todo porque sus películas apenas circulaban; es lo que sucede –y seguirá sucediendo en un futuro previsible (con Frank Borzage) que siempre ha tenido admiradores entusiastas, pero al que nunca se recuerda–, Leo McCarey, Henry King o Allan Dwan, por citar sólo cuatro, aunque tal lista podría ampliarse con facilidad, como lo prueba, en el fondo, el caso excepcional de D.W. Griffith, cada vez más desconocido (y peor entendido) pese a figurar en todas las Historias del Cine. -

Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness Historic Preservation Plan

Historic Preservation Plan For the Frank Church – River of No Return Wilderness Terrace Lakes, Big Horn Crags April 6, 2016 Report Number: SL-11-1622 R2011041300020 FC-RONRW Historic Preservation Plan April 6, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………. iii List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………….. iv Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction – Purpose and Need for the Plan……………………………………………. 1 Environmental Setting ……………………………………………………………………. 5 Cultural Setting …………………………………………………………………………... 10 Theme 1: Native American Utilization and Occupation ……………………………... 11 Theme 2: Early Euro-American Exploration ……………………………………........ 13 Theme 3: Mining ……………………………………………………………………... 14 Theme 4: Transportation …………………………………………………………....... 14 Theme 5: Agriculture and Ranching …………………………………………………. 16 Theme 6: Forest Service Administration …………………………………………….. 16 Theme 7: The Civilian Conservation Corps …………………………………………. 17 Theme 8: Recreation ………………………………………………………………..... 18 Cultural Resource Management and the Central Idaho Wilderness Act ……………........ 21 Land Management Direction and the Programmatic Agreement ………………………... 23 Desired Future Condition ………………………………………………………………… 24 Objectives ……………………………………………………………………………….... 25 Cultural Resource Identification ……………………………………………………... 25 Cultural Resource Evaluation ………………………………………………………... 26 Allocation of Cultural Resources to Management Categories ……………………….. 27 Preservation of Cultural Resources ………………………………………………. 27 Enhancement of Cultural -

The Award- Winning

The Award- Winning Rocky Mountaineer Train Vacation 6-Day Vancouver — Rocky Mountaineer — Rockies Summer Tour IEMR06 Day 1 Vancouver – Rocky Mountaineer – Kamloops Day 4 Columbia Icefield — Jasper National Park Early in the morning, make your own way to Vancouver Station to board the Icefield Parkway -- One of Canada’s national treasures and most rewarding train at 7:30AM. Please contact Rocky Mountaineer to double confirm the destinations. departure time (1-877-460-3200) Bow Lake -- It is the headwaters of the Bow River that runs south through the city Calgary and onto the Oldman River ultimately to Hudson Bay Travel from the coastal city of Vancouver to Kamloops, in the heart of British (approx. 20 mins) Columbia’s interior. Start the journey with a welcome-aboard breakfast on Columbia Icefield -- Visit the largest icefield Canadian Rockies and tour over the train. the Athabasca Glacier in a giant Ice Explorer (total approx. 3.5 hours) The train follows the scenic Fraser Valley, pass through the lush, forests and Ice Explorer (Optional) (Snocoach): a massive vehicle specially designed for winding river canyons to the desert-like inland. glacier travel. Highlights include the rushing waters of Hell’s Gate in the Fraser Canyon and Skywalk (Optional): a breathtaking view of the glacier from The Glacier the steep slopes and rock sheds along the Thompson River. Skywalk Lunchtime, you get to enjoy a well-prepared three-course lunch in the Athabasca Falls – It is rather known for the shear amount and force of the comfort of your seat. water that flows through it from the Columbia Glacier. -

Willmore Wilderness Foundation Page 16

Willmore Wilderness Foundation Page 16 Outfitting Marilyn Munroe: Interview with Bud & Annette Brewster and Janet Brewster-Stanton Below is an excerpt from Chapter One: Bud & Annette Brewster and their daugther Janet Brewster-Stanton interview, in the People & Peaks of the Panther River & Eastern Slopes. Bud Brewster was the outfitter for the movie production called River of No Return, starring Marilyn Munroe and Robert Mitchum. Sue Bud, I understand that They had one photo shoot down you worked on the feature movie at Seebe when they burnt down called the River of No Return. a cabin there, near Exshaw. Ester Richards was cooking on that job. Bud Yes, I worked on The ten percent of the film that we the River of No Return with Marilyn handled at Seebe was the dangerous Monroe and Robert Mitchum, but there part. They ran the Horseshoe Rapids have been various stories floating around near the Seebe Ranch. I got the power 0. Foreward.indd 18 12-11-27 11:41 AM that I will correct. Pictured above: company to lower the water level to I was hired by OT (Otto) make it safer. I used to work at the Bud Brewster Preminger to pick out the sites for power company. The last scene was a battle with the Indians on the Bow Photo by William Foster the shoot. Otto was the director and producer of this film. He was River. Jim Brewster was also a double courtesy of also an actor. Otto and I did this a for Robert Mitchum in that movie. year before the filming even started. -

2021 Schedule and Rates

2021 SCHEDULE AND RATES MIDDLE FORK OF THE SALMON MAIN SALMON RIVER SALMON RIVER CANYONS SELWAY RIVER (800) 262-1882 www.hughesriver.com FAMILY OWNED AND OPERATED SINCE 1976 Middle Fork of the Salmon 5 & 6 DAYS n JUNE-SEPTEMBER Idaho’s most famous mountain, wilderness, and whitewater river. Challenging rapids, crystal clear water, Native American cultural sites, pioneer history, “blue ribbon” dry fly fishing for wild westslope cutthroat trout, and natural hot springs. National Wild and Scenic River inside the vast Frank Church – River of No Return Wilderness. Headquarters: Stanley, ID. DATES LENGTH ADULT YOUTH April 16-21* 6 Days $2750 $2625 June 4-8* 5 Days $2350 $2225 June 13-18* 6 Days $2750 $2625 June 22-27 6 Days $2750 $2625 June 30-July 5 6 Days $2750 $2625 July 8-13 6 Days $2750 $2625 July 16-21 6 Days $2750 $2625 July 24-29 6 Days $2750 $2625 August 1-6 6 Days $2750 $2625 August 9-14 6 Days $2750 $2625 August 17-22 6 Days $2750 $2625 August 25-29 5 Days $2350 $2225 September 2-7* 6 Days $2750 $2625 September 12-17 6 Days $3650 $3650 September 21-25* 5 Days $3200 $3200 September 27- October 26* 6 Days $3650 $3650 *SPECIAL TRIPS April 16-21: Wildlife viewing and photography June 4-8: Hot springs and hikers June 13-18: Middle Fork – Main Salmon River combo opportunity September 2-7: Jazz trip September 21-25: Fly fish top 25 miles September 27- October 26 Days: Fly fish and chukar hunt opportunity Fishing Boats (2 anglers/boat and guide) $3650/angler (6 day), $3200/angler (5 day) Deposits to Confirm: $550/person (5 days), $700/person (6 days).