3 War Economy and State-Making in Spla Areas 1983–2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ss 9303 Ee Kapoeta North Cou

SOUTH SUDAN Kapoeta North County reference map SUDAN Pibor JONGLEI ETHIOPIA CAR DRC KENYA UGANDA EASTERN EQUATORIA Kenyi Lafon Kapoeta East Akitukomoi Kangitabok Lomokori Kapoeta North Ngigalingatun Kangibun Kalopedet Lokidangoai Nomogonjet Nawitapal Mogos Chokagiling Lorutuk Lokoges Nakwa Owetiani Nawabei Natatur Kamaliato Kanyowokol Karibungura Lokale Nagira Belengtobok Tuliabok Lokorechoke Kadapangolol Akoribok Nakwaparich Kalobeliang Wana Kachinga Lomus Lotiakara Pucwa Lopetet Nawao Lokorilam Naduket Tingayta Lodomei Kibak Nakatiti International boundary Nakapangiteng Napusiret Napulak State boundary Loriwo County boundary Kochoto Naminitotit Parpar Undetermined boundary Napusireit Nakwamoru Abyei region Kotak Kasotongor Napochorege Katiakin Nawayareng Riwoto Lokorumor Country capital Nangoletire Lokualem Lumeyen Logerain Lomidila Takankim Lobei Administrative centre/County capital Lokwamor Nacukut Naronyi Nakoret Lotiekar Namukeris Principal town Napotit Naoyatir Nakore Napureit Secondary town Lokwamiro Narubui Barach Lolepon Lotiri Paima Village Loregai Narongyet Lochuloit Kabuni Primary road Kudule Locheler Napusiria Napotpot Secondary road Nacholobo Tertiary road Budi Idong Main river Kapoeta South 0 5 10 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of Abyei area is not yet determined. Created: March 2020 | Code: SS-9303 | Sources: OCHA, SSNBS | Feedback: [email protected] | unocha.org/south-sudan | reliefweb.int/country/ssd | southsudan.humanitarianresponse.info . -

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

Linkages-Success-Stories-South-Sudan

JULY 2016 SUCCESS STORY Success on Several Levels in South Sudan In South Sudan, obtaining HIV care and treatment is difficult for people living with HIV. Only 10 percent of those eligible are currently enrolled on antiretroviral therapy (ART). But for one key population — female sex workers (FSWs) — the barriers to comprehensive HIV care and treatment are particularly daunting. Many sex workers cannot afford to lose income while waiting for services at overburdened hospitals. And those who do seek care often find providers are reluctant to serve them because of the stigma associated with sex work. Recruiting and retaining FSWs and other key populations (KPs) into the HIV cascade of services is a complex issue that demands a response at many levels. In South Sudan, LINKAGES is helping to generate a demand for services, improve access to KP-friendly services, and create a policy environment that is more conducive to the health rights of key populations. GENERATING DEMAND FOR SERVICES The justified mistrust that FSWs have for the health care system keeps many from seeking the services they need. Peer education and outreach is a critical component of engaging KPs in the HIV cascade. LINKAGES South Sudan conducted a mapping exercise to identify hotspots (or key locations) where sex work takes place. From these locations, 65 FSWs were identified and trained as peer educators to lead participatory education sessions among their peers. The sessions are designed to motivate FSWs to adopt healthy behaviors and develop the skills to do so. The sessions cover topics like condom use, regular screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), periodic testing for HIV, and enrollment into care and treatment services for those living with HIV. -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

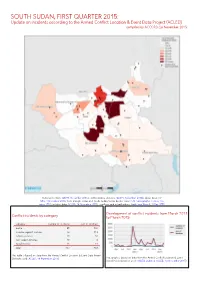

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015

SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 26 November 2015 National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, Oc- tober 2011; incident data: ACLED, 14 November 2015; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Development of conflict incidents from March 2013 Conflict incidents by category to March 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 85 596 violence against civilians 52 113 remote violence 21 16 non-violent activities 18 2 riots/protests 16 11 total 192 738 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, 14 November 2015). This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated, ACLED, 14 November 2015). SOUTH SUDAN, FIRST QUARTER 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 26 NOVEMBER 2015 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. Data on incidents in the Abyei area are not reflected in this update. -

Water for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE)

Water for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE) he first integrated water resource management (IWRM) project of its kind in South Sudan, Water Water for Eastern for Eastern Equatoria (W4EE) was launched in Components 2013 as part of the broader bilateral water Tprogramme funded through the Dutch Multiannual Equatoria (W4EE) Strategic Plan for South Sudan (2012–2015). W4EE focuses on three interrelated From the very beginning, W4EE was planned as a pilot components: IWRM programme in the Torit and Kapoeta States of The role of integrated water resource manage- Eastern Equatoria focusing on holistic management of the ment in fostering resilience, delivering economic Kenneti catchment, conflict-sensitive oversight of water Component 1: Integrated water resource management of the development, improving health, and promoting for productive use such as livestock and farming, and Kenneti catchment and surrounds peace in a long-term process. improved access to safe drinking water as well as sanitati- on and hygiene. The goal has always been to replicate key Component 2: Conflict-sensitive management of water for learnings and best practice in other parts of South Sudan. productive use contributes to increased, sustained productivity, value addition in agriculture, horticulture, and livestock The Kenneti catchment is very important to the Eastern Equatoria region for economic, social, and biodiversity reasons. The river has hydropower potential, supports the Component 3: Safely managed and climate-resilient drinking livelihoods of thousands of households, and the surroun- water services and improved sanitation and hygiene are available, ding area hosts a national park with forests and wetlands operated and maintained in a sustainable manner. as well as wild animals and migratory birds. -

United Nations Nations Unies

United Nations Nations Unies Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan condemns killing of an aid worker in Budi, Eastern Equatoria (Juba, 13 May 2021) The Humanitarian Coordinator in South Sudan, Alain Noudéhou, has condemned the killing of an aid worker in Budi, Eastern Equatoria, and called for authorities and communities to ensure that humanitarian personnel can move safely along roads and deliver assistance to the most vulnerable people. On 12 May, an aid worker was killed when criminals fired at a clearly marked humanitarian vehicle. The vehicle was part of a team of international non-governmental organizations and South Sudanese government health workers traveling to a health facility. The team was driving from Chukudum to Kapoeta in Budi County in an area that has seen several roadside ambushes this year. “I am shocked by this violent act and send my condolences to the family and colleagues of the deceased. The roads are a vital connection between humanitarian organizations and communities in need, and we must be able to move safely across the country without fear,” Mr. Noudéhou said and added: “I call on the Government to strengthen law enforcement along these roads.” This is the first aid worker killed in South Sudan in 2021. In 2020, nine aid workers were killed. *** Note to editors To learn more about humanitarian access in South Sudan, see the first quarterly access snapshot of 2021 here: https://bit.ly/3dZQtGw For further information, please contact: Emmi Antinoja, Head of Communications and Information Management, +211 92 129 6333 [email protected] Anthony Burke, Public Information Officer, +211 92 240 6014 and [email protected] OCHA press releases are available at www.unocha.org/south-sudan or www.reliefweb.int. -

The War(S) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace

Conflict Research Programme The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace Flora McCrone in collaboration with the Bridge Network About the Authors Flora McCrone is an independent researcher based in East Africa. She has specialised in research on conflict, armed groups, and political transition across the Horn region for the past nine years. Flora holds a master’s degree in Human Rights from LSE and a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Durham University. The Bridge Network is a group of eight South Sudanese early career researchers based in Nimule, Gogrial, Yambio, Wau, Leer, Mayendit, Abyei, Juba PoC 1, and Malakal. The Bridge Network members are embedded in the communities in which they conduct research. The South Sudanese researchers formed the Bridge Network in November 2017. The team met annually for joint analysis between 2017-2020 in partnership with the Conflict Research Programme. About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme hosted by LSE IDEAS, the university’s foreign policy think tank. It is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. © Flora McCrone and the Bridge Network, February 2021. This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Risk Assessment of the Mining Industry in South Sudan: Towards a Framework for Transparency and Accountability

RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE MINING INDUSTRY IN SOUTH SUDAN: TOWARDS A FRAMEWORK FOR TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY Peter Adwok Nyaba July 2019 Appreciation and acknowledgement This study, “Risk Assessment of the Mining Industry in South Sudan: Towards a Framework for Transparency and Accountability”, was commissioned by Ebony Center for Strategic Studies. It commenced in the second week of May 2019 and was completed by the first week of June. Mr. Azaria Gillo, a geologist working in the Ministry of Mining was my research assistant and his contribution led to the success of the research work. I thank him very much. The preliminary report of this study was discussed in an Ebony Centre’s function DPF/TF on Saturday 20 July 2019 attended by more than a hundred participants. The Under-Secretaries of the Ministries of Mining, Forestry and Environment as well as the Director of Environmental and Natural Resources Program in the Sudd Institute were the main discussants. Their technical and professional views were incorporated into the final report. I want to avail myself of this opportunity to appreciate and acknowledge the assistance rendered to us by the Under-Secretary, Dr. Andu Ezbon Adde, in granting permission to collect information and data from the Ministry of Mining data base and writing letters to the State Governments of Kapoeta and Juba to assist us in the research. Last but not least, my thanks and appreciation go to Ebony Center for Strategic Studies, for availing me the opportunity to undertake an exercise that is likely to contribute towards strengthening the institutions and instruments of the mining industry in the Republic of South Sudan.