Ealing: Light & Dark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mini Brochure

filmworks is designed with star quality – inspired by the past, celebrating the future Ealing’s Thrilling New Lifestyle Quarter Computer-generated images are indicative only. Page 01 picture this IN TUNE WITH EALING’S HISTORY, THE STAR OF FILMWORKS WILL BE THE EIGHT-SCREEN PICTUREHOUSE CINEMA, TOGETHER WITH PLANET ORGANIC’S FRESH AND NATURAL PRODUCE. Eat well, live better, thanks to Planet Organic before heading to the movies. Filmworks offers an adventurous mix of shops, restaurants and bars; all perfectly located around a central and open piazza. PagePage 02 18 Lifestyle images are indicative only. Page 04 Computer-generated image is indicative only. Hollywood stars Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and William Holden were a few of the big dazzling names to step foot in Ealing Studios. history THE FORUM CINEMA OPENED IN 1934 WITH ‘LIFE, LOVE AND LAUGHTER’. A COMEDY FILMED METRES AWAY, AT THE WORLD- FAMOUS EALING STUDIOS. The old cinema façade in 1963. Designed by John Stanley Beard, the old cinema’s classical colonnades create a grand entrance to the Filmworks quarter. Remarkably, the cinema building was relatively new compared to Ealing Studios, built in 1902. The first of its kind, with classics like The Ladykillers and recent successes The Theory of Everything and Downton Abbey, it is synonymous with the British film industry. Passport to Pimlico A 1949 British comedy starring Stanley Holloway in which a South London Street declares its independence. The Ladykillers A classic Ealing comedy starring Alec Guinness who becomes part of a ragtag criminal gang that runs into trouble when their landlady discovers there’s more to their string quartet than meets the eye. -

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Filmworks Brochure

filmworks is designed with star quality – inspired by the past, celebrating the future Ealing’s Thrilling New Lifestyle Quarter Computer-generated images are indicative only. Page 01 picture this IN TUNE WITH EALING’S HISTORY, THE STAR OF FILMWORKS WILL BE THE EIGHT-SCREEN PICTUREHOUSE CINEMA, TOGETHER WITH PLANET ORGANIC’S FRESH AND NATURAL PRODUCE, AND VAPIANO’S DELIGHTFUL ITALIAN MENU. Eat well, live better, thanks to Planet Organic. Dine and enjoy the freshly prepared food at Vapiano before heading to the movies. Filmworks offers an adventurous mix of shops, restaurants and bars; all perfectly located around a central and open piazza. Page 02 Lifestyle images are indicative only. Page 04 Computer-generated image is indicative only. Hollywood stars Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and William Holden were a few of the big dazzling names to step foot in Ealing Studios. history THE FORUM CINEMA OPENED IN 1934 WITH ‘LIFE, LOVE AND LAUGHTER’. A COMEDY FILMED METRES AWAY, AT THE WORLD- FAMOUS EALING STUDIOS. The old cinema façade in 1963. Designed by John Stanley Beard, the old cinema’s classical colonnades create a grand entrance to the Filmworks quarter. Remarkably, the cinema building was relatively new compared to Ealing Studios, built in 1902. The frst of its kind, with classics like The Ladykillers and recent successes The Theory of Everything and Downton Abbey, it is synonymous with the British flm industry. Passport to Pimlico A 1949 British comedy starring Stanley Holloway in which a South London Street declares its independence. The Ladykillers A classic Ealing comedy starring Alec Guinness who becomes part of a ragtag criminal gang that runs into trouble when their landlady discovers there’s more to their string quartet than meets the eye. -

Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson

23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson Save 0 Filmography Show less 1971 Creatures the World Forgot Special Effects 1969 Desert Journey Special Effects 1969 Autokill Special Effects 1966 The Heroes of Telemark [Special Effects] 1965 The Secret of Blood Island Special Effects 1965 The Brigand of Kandahar Special Effects 1964 The Long Ships Special Effects 1964 The Gorgon Special Effects 1962 In Search of the Castaways Special Effects 1960 The Brides of Dracula Special Effects 1959 Too Many Crooks [Special Processes] 1959 North West Frontier Special Effects 1959 The Hound of the Baskervilles Special Effects 1959 Ferry to Hong Kong Special Effects 1958 Dracula Special Effects 1957 The Steel Bayonet Special Effects 1957 Campbell's Kingdom Special Effects 1956 The Ladykillers Special Effects 1956 House of Secrets Special Processes (uncredited) 1956 Reach for the Sky Models (uncredited) 1955 Out of the Clouds Special Effects 1955 The Ship That Died of Shame Special Effects 1955 The Night My Number Came Up Special Effects 1955 Touch and Go Special Effects 1954 The Love Lottery Special Effects 1954 The 'Maggie' Special Effects https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 1/2 23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI 1953 The Cruel Sea Special Effects 1953 The Titfield Thunderbolt Special Effects 1952 His Excellency Special Effects 1952 Mandy [Special Effects] 1952 I Believe in You Special Effects (uncredited) 1952 The Gentle Gunman Special Effects 1952 Secret People Special Effects 1951 Pool of London Special Effects 1951 The Man in the White Suit Special Effects 1951 The Lavender Hill Mob Special Effects 1950 Cage of Gold Special Effects 1950 Dance Hall Special Effects 1950 The Magnet Special Effects 1949 Kind Hearts and Coronets Special Effects 1949 Train of Events Special Effects 1949 Whisky Galore! Special Effects 1948 Scott of the Antarctic Special Effects 1947 The October Man [Stage Effects] [Model Miniatures] 1947 Black Narcissus [Synthetic Pictorial Effects] https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 2/2. -

JOURNAL 0 F the B B C July 1 7

PROGRAMMES FOR July 1�7 JOURNAL 0 F THE B B C H.M. The King at the Isle of Man Tynwald Ceremony Thursday, 6.20 p.m. Canada's Dominion Day Programme ...... Sunday, 7.0 p.m. ' Good Old London ' : a tribute to the wartime Civil Defence Services and personnel of the L.C.C. From Royal Albert Hall Sunday, 7.30 p.m.* 'Independence, Missouri,' President Truman's home- town : a 'Transatlantic Call' Programme Tuesday, 6.30 p.m. 'The War in the Pacific,' part 1 : The months of Defeat .................................... Thursday, 8.0 p.m. Perchance to Dream,' thirty-five-minute excerpt from The London Hippodrome ...............Friday, 6.55 p.m. PLAYS ' Poor Dear Mr. Overt,' by Henry James Sunday, 3.45 p.m. 'Squirrel's Cage,' byTyroneGuthrie. Monday, 9.30 p.m. 'Mr. Lucas,' by Francis Durbridge ...... Tuesday, 8.15 p.m. 'Love from a Stranger,' by Agatha Christie and Frank Vosper '. Wednesday, 7.30 p.m.* 'King Henry the Fourth' episode 6 Thursday, 9.30 p.m. Marius Goring in 'Edmund Kean, by Hugh Miller Friday, 8.0 p.m. Edward Chapman and Adele Dixon in J. B. Priestley's 'The Good Companions' ............. Saturday, 9.20 p.m. VARIETY ' Fools' Paradise,' with Naunton Wayne and Basil Radford: part 4 Monday, 8.30 p.m. The Carroll Levis Show .................. Tuesday, 8.15 p.m.* 'Stanelli Throws a Party' Tuesday, 9.15 p.m.* Henry Hall's Guest Night ............ Wednesday, 6.30 p.m. 'Northern Music-Hall: from Carlisle ...Thursday, 8.30 p.m. Merry-Go-Round' : Air Force Edition .. -

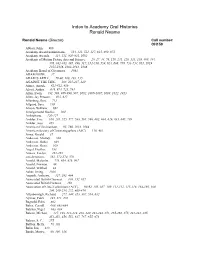

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

EALING-EN EPOKE Før Han Dræbtes I Krigen

særpræg, som langsomt skabte begrebet Ealing-film. Balcon kom til Ealing med en ret impo nerende indsats bag sig. Allerede i tyverne havde han givet den unge Hitchcock sine første chancer, og som producer havde han indspillet film som „The lodger“ (1926), „The good companions“ (1932), „Rome Express" (med Conrad Veidt, 1932), Flaher- tys „Man of Aran“ (1933), „Jøden Siiss" (1934) og „D e 39 trin“ (1 9 3 5 ). På Ealing Studios mærkedes hans indflydelse hurtigt. En helt ny og mere realistisk præget perio de i selskabets historie indledtes med bokse filmen „There ain’t no justice" (1938), der handlede om korruptionen i bokseverdenen og udspilledes på en baggrund hentet lige ud af engelsk hverdag. Den var iscenesat af en af britisk films mest talentfulde unge begavelser, Pen Tenny son (et oldebarn af Den afdøde engelske filmtegner og -kritiker den berømte digter), og det var også ham, Richard Winningtons opfattelse af Sidney der det følgende år instruerede „The proud James, Stanley Holloway og Alec Guinness i den typiske Ealingkomedie »Masser af Guld«. valley", som skildrede livet blandt walisiske minearbejdere, og hvori Paul Robeson spil lede en af hovedrollerne. Pen Tennyson nåe de aldrig helt at indfri de løfter, han gav med disse første arbejder. Han fik kun lov til at lave endnu en film, „C onvoy" (1 9 4 0 ), EALING-EN EPOKE før han dræbtes i krigen. M en forstærkninger var allerede under AF MOGENS FØNSS vejs. Fra den engelske stats berømte doku mentargruppe „Crown Film Unit" hentede Fredag den 13. januar blev en sort dag Michael Balcon Cavalcanti og Harry Watt, for engelsk film. -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

Download (2631Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/58603 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. A Special Relationship: The British Empire in British and American Cinema, 1930-1960 Sara Rose Johnstone For Doctorate of Philosophy in Film and Television Studies University of Warwick Film and Television Studies April 2013 ii Contents List of figures iii Acknowledgments iv Declaration v Thesis Abstract vi Introduction: Imperial Film Scholarship: A Critical Review 1 1. The Jewel in the Crown in Cinema of the 1930s 34 2. The Dark Continent: The Screen Representation of Colonial Africa in the 1930s 65 3. Wartime Imperialism, Reinventing the Empire 107 4. Post-Colonial India in the New World Order 151 5. Modern Africa according to Hollywood and British Filmmakers 185 6. Hollywood, Britain and the IRA 218 Conclusion 255 Filmography 261 Bibliography 265 iii Figures 2.1 Wee Willie Winkie and Susannah of the Mounties Press Book Adverts 52 3.1 Argentinian poster, American poster, Hungarian poster and British poster for Sanders of the River 86 3.2 Paul Robeson and Elizabeth Welch arriving in Africa in Song of Freedom 92 3.3 Cedric Hardwicke and un-credited actor in Stanley and Livingstone -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.