C5a Impairs Phagosomal Maturation in the Neutrophil Through Phosphoproteomic Remodelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Gene Expression Data for Gene Ontology

ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Robert Daniel Macholan May 2011 ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION Robert Daniel Macholan Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Zhong-Hui Duan Dr. Chien-Chung Chan _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Chien-Chung Chan Dr. Chand K. Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Yingcai Xiao Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT A tremendous increase in genomic data has encouraged biologists to turn to bioinformatics in order to assist in its interpretation and processing. One of the present challenges that need to be overcome in order to understand this data more completely is the development of a reliable method to accurately predict the function of a protein from its genomic information. This study focuses on developing an effective algorithm for protein function prediction. The algorithm is based on proteins that have similar expression patterns. The similarity of the expression data is determined using a novel measure, the slope matrix. The slope matrix introduces a normalized method for the comparison of expression levels throughout a proteome. The algorithm is tested using real microarray gene expression data. Their functions are characterized using gene ontology annotations. The results of the case study indicate the protein function prediction algorithm developed is comparable to the prediction algorithms that are based on the annotations of homologous proteins. -

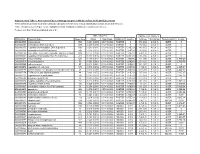

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A. -

Supplementary Material and Methods

Supplementary material and methods Generation of cultured human epidermal sheets Normal human epidermal keratinocytes were isolated from human breast skin. Keratinocytes were grown on a feeder layer of irradiated human fibroblasts pre-seeded at 4000 cells /cm² in keratinocyte culture medium (KCM) containing a mix of 3:1 DMEM and HAM’s F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), supplemented with 10% FCS, 10ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), 0.12 IU/ml insulin (Lilly, Saint- Cloud, France), 0.4 mg/ml hydrocortisone (UpJohn, St Quentin en Yvelelines, France) , 5 mg/ml triiodo-L- thyronine (Sigma, St Quentin Fallavier, France), 24.3 mg/ml adenine (Sigma), isoproterenol (Isuprel, Hospira France, Meudon, France) and antibiotics (20 mg/ml gentamicin (Phanpharma, Fougères, France), 100 IU/ml penicillin (Phanpharma), and 1 mg/ml amphotericin B (Phanpharma)). The medium was changed every two days. NHEK were then cultured over a period of 13 days according to the protocol currently used at the Bank of Tissues and Cells for the generation of clinical grade epidermal sheets used for the treatment of severe extended burns (Ref). When needed, cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA 0.05% (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and collected for analysis. Clonogenic assay Keratinocytes were seeded on a feeder layer of irradiated fibroblasts, at a clonal density of 10-20 cells/cm² and cultivated for 10 to 14 days. Three flasks per tested condition were fixed and colored in a single 30 mns step using rhodamine B (Sigma) diluted at 0.01 g/ml in 4% paraformaldehyde. In each tested condition, cells from 3 other flasks were numerated after detachment by trypsin treatment. -

High Resolution Physical and Comparative Maps of Horse

HIGH RESOLUTION PHYSICAL AND COMPARATIVE MAPS OF HORSE CHROMOSOMES 14 (ECA14) AND 21 (ECA21) A Thesis by GLENDA GOH Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May 2005 Major Subject: Genetics HIGH RESOLUTION PHYSICAL AND COMPARATIVE MAPS OF HORSE CHROMOSOMES 14 (ECA14) AND 21 (ECA21) A Thesis by GLENDA GOH Submitted to Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved as to style and content by: _________________________ _________________________ Bhanu P. Chowdhary Loren C. Skow (Chair of Committee) (Member) _________________________ _________________________ James N. Derr James E. Womack (Member) (Member) _________________________ _________________________ Geoffrey Kapler Evelyn Tiffany-Castiglioni (Chair of Genetics Faculty) (Head of Department) May 2005 Major Subject: Genetics iii ABSTRACT High Resolution Physical and Comparative Maps of Horse Chromosomes 14 (ECA14) and 21 (ECA21). (May 2005) Glenda Goh, B.S. (Hons.), Flinders University of South Australia Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Bhanu P. Chowdhary In order to identify genes or markers responsible for economically important traits in the horse, the development of high resolution gene maps of individual equine chromosomes is essential. We herein report the construction of high resolution physically ordered radiation hybrid (RH) and comparative maps for horse chromosomes 14 and 21 (ECA14 and ECA21). These chromosomes predominantly share correspondence with human chromosome 5 (HSA5), though a small region on the proximal part of ECA21 corresponds to a ~5Mb region from the short arm of HSA19. The map for ECA14 consists of 128 markers (83 Type I and 45 Type II) and spans a total of 1828cR.Compared to this, the map of ECA21 is made up of 90 markers (64 Type I and 26 Type II), that segregate into two linkage groups spanning 278 and 760cR each. -

Mai Muudatuntuu Ti on Man Mini

MAIMUUDATUNTUU US009809854B2 TI ON MAN MINI (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 ,809 ,854 B2 Crow et al. (45 ) Date of Patent : Nov . 7 , 2017 Whitehead et al. (2005 ) Variation in tissue - specific gene expression ( 54 ) BIOMARKERS FOR DISEASE ACTIVITY among natural populations. Genome Biology, 6 :R13 . * AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Villanueva et al. ( 2011 ) Netting Neutrophils Induce Endothelial SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS Damage , Infiltrate Tissues, and Expose Immunostimulatory Mol ecules in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus . The Journal of Immunol @(71 ) Applicant: NEW YORK SOCIETY FOR THE ogy , 187 : 538 - 552 . * RUPTURED AND CRIPPLED Bijl et al. (2001 ) Fas expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes in MAINTAINING THE HOSPITAL , systemic lupus erythematosus ( SLE ) : relation to lymphocyte acti vation and disease activity . Lupus, 10 :866 - 872 . * New York , NY (US ) Crow et al . (2003 ) Microarray analysis of gene expression in lupus. Arthritis Research and Therapy , 5 :279 - 287 . * @(72 ) Inventors : Mary K . Crow , New York , NY (US ) ; Baechler et al . ( 2003 ) Interferon - inducible gene expression signa Mikhail Olferiev , Mount Kisco , NY ture in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus . PNAS , (US ) 100 ( 5 ) : 2610 - 2615. * GeneCards database entry for IFIT3 ( obtained from < http : / /www . ( 73 ) Assignee : NEW YORK SOCIETY FOR THE genecards. org /cgi - bin / carddisp .pl ? gene = IFIT3 > on May 26 , 2016 , RUPTURED AND CRIPPLED 15 pages ) . * Navarra et al. (2011 ) Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients MAINTAINING THE HOSPITAL with active systemic lupus erythematosus : a randomised , placebo FOR SPECIAL SURGERY , New controlled , phase 3 trial . The Lancet , 377 :721 - 731. * York , NY (US ) Abramson et al . ( 1983 ) Arthritis Rheum . -

Mechanisms of Up-Regulation of Ubiquitin-Proteasome Activity in The

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.23.003053; this version posted March 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Mechanisms of up-regulation of Ubiquitin-Proteasome activity in the absence of NatA dependent N-terminal acetylation Ilia Kats1,2, Marc Kschonsak1,3, Anton Khmelinskii4, Laura Armbruster1,5, Thomas Ruppert1 and Michael Knop1,6,* 1 Zentrum für Molekulare Biologie der Universität Heidelberg (ZMBH), DKFZ-ZMBH Alliance, Im Neuenheimer Feld 282, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. 2 present address: German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Im Neuenheimer Feld 280, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 3 present address: Department of Structural Biology, Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA. 4 Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB), Ackermannweg 4, 55128 Mainz, Germany. 5 present address: Centre for Organismal Studies (COS), Im Neuenheimer Feld 360, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 6 Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), DKFZ-ZMBH Alliance, Im Neuenheimer Feld 280, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. * corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract N-terminal acetylation is a prominent protein modification and inactivation of N-terminal acetyltransferases (NATs) cause protein homeostasis stress. Using multiplexed protein stability (MPS) profiling with linear ubiquitin fusions as reporters for the activity of the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) we observed increased UPS activity in NatA, but not NatB or NatC mutants. We find several mechanisms contributing to this behavior. First, NatA-mediated acetylation of the N-terminal ubiquitin independent degron regulates the abundance of Rpn4, the master regulator of the expression of proteasomal genes. -

Prioritizing Parkinson’S Disease Genes Using Population-Scale

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08912-9 OPEN Prioritizing Parkinson’s disease genes using population-scale transcriptomic data Yang I. Li1, Garrett Wong2, Jack Humphrey 3,4 & Towfique Raj2 Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 41 susceptibility loci asso- ciated with Parkinson’s Disease (PD) but identifying putative causal genes and the underlying mechanisms remains challenging. Here, we leverage large-scale transcriptomic datasets to 1234567890():,; prioritize genes that are likely to affect PD by using a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) approach. Using this approach, we identify 66 gene associations whose predicted expression or splicing levels in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLFPC) and peripheral monocytes are significantly associated with PD risk. We uncover many novel genes associated with PD but also novel mechanisms for known associations such as MAPT, for which we find that variation in exon 3 splicing explains the common genetic association. Genes identified in our analyses belong to the same or related pathways including lysosomal and innate immune function. Overall, our study provides a strong foundation for further mechanistic studies that will elucidate the molecular drivers of PD. 1 Section of Genetic Medicine, Department of Medicine, and Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637 IL, USA. 2 Departments of Neuroscience, and Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Ronald M. Loeb Center for Alzheimer’s disease, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York 10029 NY, USA. 3 UCL Genetics Institute, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK. 4 Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Institute of Neurology, London WC1E 6BT, UK. These authors contributed equally: Yang I. -

Population-Haplotype Models for Mapping and Tagging Structural Variation Using Whole Genome Sequencing

Population-haplotype models for mapping and tagging structural variation using whole genome sequencing Eleni Loizidou Submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Section of Genomics of Common Disease Department of Medicine Imperial College London, 2018 1 Declaration of originality I hereby declare that the thesis submitted for a Doctor of Philosophy degree is based on my own work. Proper referencing is given to the organisations/cohorts I collaborated with during the project. 2 Copyright Declaration The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work 3 Abstract The scientific interest in copy number variation (CNV) is rapidly increasing, mainly due to the evidence of phenotypic effects and its contribution to disease susceptibility. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) which are abundant in the human genome have been widely investigated in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Despite the notable genomic effects both CNVs and SNPs have, the correlation between them has been relatively understudied. In the past decade, next generation sequencing (NGS) has been the leading high-throughput technology for investigating CNVs and offers mapping at a high-quality resolution. We created a map of NGS-defined CNVs tagged by SNPs using the 1000 Genomes Project phase 3 (1000G) sequencing data to examine patterns between the two types of variation in protein-coding genes. -

Rabbit Anti-ZFYVE16/FITC Conjugated Antibody

SunLong Biotech Co.,LTD Tel: 0086-571- 56623320 Fax:0086-571- 56623318 E-mail:[email protected] www.sunlongbiotech.com Rabbit Anti-ZFYVE16/FITC Conjugated antibody SL19157R-FITC Product Name: Anti-ZFYVE16/FITC Chinese Name: FITC标记的Zinc finger protein结构域ZFYVE16抗体 AI035632; B130024H06Rik; B130031L15; DKFZp686E13162; Endofin; Endosomal associated FYVE domain protein; Endosome associated FYVE domain protein; Endosome-associated FYVE domain protein; KIAA0305; KIAA0305;; mKIAA0305; Alias: OTTMUSP00000029589; RGD1564784; ZFY16_HUMAN; ZFYVE16; Zinc finger FYVE domain containing protein 16; Zinc finger FYVE domain-containing protein 16; Zinc finger, FYVE domain containing 16. Organism Species: Rabbit Clonality: Polyclonal React Species: Human,Mouse,Rat,Pig,Cow,Horse,Rabbit,Sheep, ICC=1:50-200IF=1:50-200 Applications: not yet tested in other applications. optimal dilutions/concentrations should be determined by the end user. Molecular weight: 88kDa Form: Lyophilized or Liquid Concentration: 1mg/ml immunogen: KLHwww.sunlongbiotech.com conjugated synthetic peptide derived from human ZFYVE16 Lsotype: IgG Purification: affinity purified by Protein A Storage Buffer: 0.01M TBS(pH7.4) with 1% BSA, 0.03% Proclin300 and 50% Glycerol. Store at -20 °C for one year. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. The lyophilized antibody is stable at room temperature for at least one month and for greater than a year Storage: when kept at -20°C. When reconstituted in sterile pH 7.4 0.01M PBS or diluent of antibody the antibody is stable for at least two weeks at 2-4 °C. background: This gene encodes an endosomal protein that belongs to the FYVE zinc finger family of Product Detail: proteins. The encoded protein is thought to regulate membrane trafficking in the endosome. -

Nº Ref Uniprot Proteína Péptidos Identificados Por MS/MS 1 P01024

Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 26/09/2021. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Nº Ref Uniprot Proteína Péptidos identificados 1 P01024 CO3_HUMAN Complement C3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=C3 PE=1 SV=2 por 162MS/MS 2 P02751 FINC_HUMAN Fibronectin OS=Homo sapiens GN=FN1 PE=1 SV=4 131 3 P01023 A2MG_HUMAN Alpha-2-macroglobulin OS=Homo sapiens GN=A2M PE=1 SV=3 128 4 P0C0L4 CO4A_HUMAN Complement C4-A OS=Homo sapiens GN=C4A PE=1 SV=1 95 5 P04275 VWF_HUMAN von Willebrand factor OS=Homo sapiens GN=VWF PE=1 SV=4 81 6 P02675 FIBB_HUMAN Fibrinogen beta chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGB PE=1 SV=2 78 7 P01031 CO5_HUMAN Complement C5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=C5 PE=1 SV=4 66 8 P02768 ALBU_HUMAN Serum albumin OS=Homo sapiens GN=ALB PE=1 SV=2 66 9 P00450 CERU_HUMAN Ceruloplasmin OS=Homo sapiens GN=CP PE=1 SV=1 64 10 P02671 FIBA_HUMAN Fibrinogen alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGA PE=1 SV=2 58 11 P08603 CFAH_HUMAN Complement factor H OS=Homo sapiens GN=CFH PE=1 SV=4 56 12 P02787 TRFE_HUMAN Serotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=TF PE=1 SV=3 54 13 P00747 PLMN_HUMAN Plasminogen OS=Homo sapiens GN=PLG PE=1 SV=2 48 14 P02679 FIBG_HUMAN Fibrinogen gamma chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGG PE=1 SV=3 47 15 P01871 IGHM_HUMAN Ig mu chain C region OS=Homo sapiens GN=IGHM PE=1 SV=3 41 16 P04003 C4BPA_HUMAN C4b-binding protein alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=C4BPA PE=1 SV=2 37 17 Q9Y6R7 FCGBP_HUMAN IgGFc-binding protein OS=Homo sapiens GN=FCGBP PE=1 SV=3 30 18 O43866 CD5L_HUMAN CD5 antigen-like OS=Homo