From the „Death of Literature‟ to the „New Subjectivity‟: Examining the Interaction of Utopia and Nostalgia in Peter Schneider‟ S Lenz, Hans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tradition Und Moderne in Der Literatur Der Schweiz Im 20. Jahrhundert

HUMANIORA: GERMANISTICA 4 HUMANIORA: GERMANISTICA 4 Tradition und Moderne in der Literatur der Schweiz im 20. Jahrhundert Beiträge zur Internationalen Konferenz zur deutschsprachigen Literatur der Schweiz 26. bis 27. September 2007 herausgegeben von EVE PORMEISTER HANS GRAUBNER Reihe HUMANIORA: GERMANISTICA der Universität Tartu Wissenschaftlicher Beirat: Anne Arold (Universität Tartu), Dieter Cherubim (Georg-August- Universität Göttingen), Heinrich Detering (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen), Hans Graubner (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen), Reet Liimets (Universität Tartu), Klaus-Dieter Ludwig (Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin), Albert Meier (Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel), Dagmar Neuendorff (Ǻbo Akademie Finnland), Henrik Nikula (Universität Turku), Eve Pormeister (Universität Tartu), Mari Tarvas (Universität Tallinn), Winfried Ulrich (Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel), Carl Wege (Universität Bremen). Layout: Aive Maasalu Einbandgestaltung: Kalle Paalits ISSN 1736–4345 ISBN 978–9949–19–018–8 Urheberrecht: Alle Rechte an den Beiträgen verbleiben bei den Autoren, 2008 Tartu University Press www.tyk.ee Für Unterstützung danken die Herausgeber der Stiftung Pro Helvetia INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort. ............................................................................................... 9 Eve Pormeister (Tartu). „JE MEHR DIFFERENZIERUNG, DESTO MEHR KULTUR“. BEGRÜSSUNG .................................................. 12 Ivana Wagner (Helsinki/Schweiz). NUR DAS GESPROCHENE WORT GILT. BEGRÜSSUNG DURCH DIE BOTSCHAFTSRÄTIN, -

Schweizer Gegenwartsliteratur

513 Exkurs 1: » ... fremd und fern wie in Grönland«• Schweizer Gegenwartsliteratur Die Schweiz, von Deutschland aus betrachtet-da entsteht das Bild einer Die Schweiz Insel: eine Insel der Stabilität und Solidität und Neutralität inmitten eines Meeres politisch-ökonomischer Unwägbarkeiten und Unwegsam- keiten. Eine Zwingburg der Finanz- und Währungshoheit, eine calvinisti- sche Einsiedelei, in der das Bankgeheimnis so gut gehütet wird wie an- dernorts kaum das Beichtgeheimnis, getragen und geprägt von einem tra ditionsreichen Patriarchat, das so konservativ fühlt wie es republikanisch handelt, umstellt von einem panoramatischen Massiv uneinnehmbarer Gipfelriesen. Ein einziger Anachronismus, durchsäumt von blauen Seen und grünen Wiesen und einer Armee, die ihresgleichen sucht auf der Welt. Ein Hort »machtgeschützter Innerlichkeit<<, mit Thomas Mann zu reden - eine Insel, von Deutschland aus betrachtet. Mag dieses Postkartenbild auch als Prospektparodie erscheinen - es entbehrt doch nicht des Körnchens Wahrheit, das bisweilen auch Pro spekte in sich tragen. >>Was die Schweiz für viele Leute so anziehend macht, daß sie sich hier niederzulassen wünschen, ist vielerlei<<, wußte schon zu Beginn der 60er Jahre ein nicht unbekannter Schweizer Schrift steller, Max Frisch nämlich, zu berichten: >>ein hoher Lebensstandard für solche, die ihn sich leisten können; Erwerbsmöglichkeit; die Gewähr eines Rechtsstaates, der funktioniert. Auch liegt die Schweiz geogra phisch nicht abseits: sofort ist man in Paris oder Mailand oder Wien. Man muß hier keine abseitige Sprache lernen; wer unsere Mundart nicht ver steht, wird trotzdem verstanden.( ...) Die Währung gilt als stabil. Die Po litik, die die Schweizer beschäftigt, bleibt ihre Familienangelegenheit.<< Kurz: >>Hier läßt sich leben, >Europäer sein<.<< Soweit das Bild- von der Schweiz aus betrachtet-, das sich die Deutschen von ihr machen. -

German Ecocriticism an Overview

Citation for published version: Goodbody, A 2014, German ecocriticism: an overview. in G Garrard (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism. Oxford Handbooks of Literature, Oxford University Press, Oxford, U. K., pp. 547-559. Publication date: 2014 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 ‘German Ecocriticism: An Overview’1 Axel Goodbody (for Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism, ed. Greg Garrard) The contrast between the largely enthusiastic response to ecocriticism in the Anglophone academy and its relative invisibility in the German-speaking world is a puzzle. Why has it yet to gain wider recognition as a field of literary study in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, countries in whose philosophy and cultural tradition nature features so prominently, whose people are shown by international surveys of public opinion to show a high degree of environmental concern, and where environmental issues rank consistently high on the political agenda? One reason may be that German scientists, political thinkers and philosophers have been pioneers in ecology since Humboldt and Haeckel, and non-fiction books have served as the primary medium of public debate on environmental issues in Germany. -

Contemporary Anarchist Studies

Contemporary Anarchist Studies This volume of collected essays by some of the most prominent academics studying anarchism bridges the gap between anarchist activism on the streets and anarchist theory in the academy. Focusing on anarchist theory, pedagogy, methodologies, praxis, and the future, this edition will strike a chord for anyone interested in radical social change. This interdisciplinary work highlights connections between anarchism and other perspectives such as feminism, queer theory, critical race theory, disability studies, post- modernism and post-structuralism, animal liberation, and environmental justice. Featuring original articles, this volume brings together a wide variety of anarchist voices whilst stressing anarchism’s tradition of dissent. This book is a must buy for the critical teacher, student, and activist interested in the state of the art of anarchism studies. Randall Amster, J.D., Ph.D., professor of Peace Studies at Prescott College, publishes widely in areas including anarchism, ecology, and social movements, and is the author of Lost in Space: The Criminalization, Globalization , and Urban Ecology of Homelessness (LFB Scholarly, 2008). Abraham DeLeon, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the University of Rochester in the Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development. His areas of interest include critical theory, anarchism, social studies education, critical pedagogy, and cultural studies. Luis A. Fernandez is the author of Policing Dissent: Social Control and the Anti- Globalization Movement (Rutgers University Press, 2008). His interests include protest policing, social movements, and the social control of late modernity. He is a professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northern Arizona University. Anthony J. Nocella, II, is a doctoral student at Syracuse University and a professor at Le Moyne College. -

Inhalt Lebensfahrt

Inhalt Vorwort 17 Lebensfahrt H. C. ARTMANN mit einem jähr ein kind 21 RICARDA HUCH Die Lebensalter 21 WILHELM BUSCH Lebensfahrt 23 FRIEDRICH RÜCKERT Des ganzen Menschen und des einzelnen Geschichte 25 FRIEDRICH HÖLDERLIN Lebenslauf 25 ERNST JANDL sommerlied 26 MAX DAUTHENDEY Vorm Springbrunnenstrahl 27 ERICH KÄSTNER Das Eisenbahngleichnis 29 RUDOLF OTTO WIEMER partizip perfekt 30 KLABUND Woher 31 5 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/988814811 gescannt durch Geburt und Geburtstage EDUARD MÖRIKE Storchenbotschaft 32 DURS GRÜNBEIN Begrüßung einer Prinzessin 33 HANS MAGNUS ENZENSBERGER Geburtsanzeige 36 GEORG TRAKL Geburt 37 PAULA LUDWIG Kommt nicht mit jeder Geburt 38 H. C. ARTMANN herrgott bin ich froh ich habe geburtstag 39 REINER KUNZE Mein fünfundzwanzigster Geburtstag 40 THEODOR STORM Am Geburtstage 43 MARTIN GREIF An meinem fünfzigsten Geburtstag . 44 RICARDA HUCH Einer Freundin zum sechzigsten Geburtstage 44 ELISABETH BORCHERS Vergessener Geburtstag 45 Kindheit FRIEDERIKE MAYRÖCKER Kindersommer 46 HUGO BALL Kind und Traum 47 FRIEDRICH HEBBEL Auf ein schlummerndes Kind 48 PETER HUCHEL Das Kinderfenster 48 MASCHA KALEKO Notizen 52 KARL KROLOW Kindheit 53 FRIEDRICH HÖLDERLIN Da ich ein Knabe war 54 GÜNTER EICH Kindheit 55 GEORG TRAKL Kindheit 56 HERMANN HESSE Julikinder 57 Schul- und Jugendzeit H. C. ARTMANN Zueignung 58 ELSE LASKER-SCHÜLER Schulzeit 59 MASCHA KALEKO Autobiographisches 61 GÜNTER GRASS Schulpause 62 ALBERT EHRENSTEIN Matura 63 ANNETTE VON DROSTE-HÜLSHOFF Die Schulen 63 CHRISTINE BUSTA Einem jungen Menschen zwischen Tür und Angel 64 ERICH KÄSTNER Marionettenballade 65 SARAH KIRSCH Flügelschlag 66 Lebenspartner JOSEPH VON EICHENDORFF Liebe, wunderschönes Leben 67 THEODOR STORM Wer je gelebt in Liebesarmen 69 ADELBERT VON CHAMISSO Hochzeitlieder 69 GEORG PHILIPP HARSDÖRFFER / JOHANN KLAJ Hochzeits-Wunsch 71 EDUARD C. -

The Ninth Country: Handke's Heimat and the Politics of Place

The Ninth Country: Peter Handke’s Heimat and the Politics of Place Axel Goodbody [Unpublished paper given at the conference ‘The Dynamics of Memory in the New Europe: National Memories and the European Project’, Nottingham Trent University, September 2007.] Abstract Peter Handke’s ‘Yugoslavia work’ embraces novels and plays written over the last two decades as well as his 5 controversial travelogues and provocative media interventions since the early 1990s. It comprises two principal themes: criticism of media reporting on the conflicts which accompanied the break-up of the Yugoslavian federal state, and his imagining of a mythical, utopian Slovenia, Yugoslavia and Serbia. An understanding of both is necessary in order to appreciate the reasons for his at times seemingly bizarre and perverse, and in truth sometimes misguided statements on Yugoslav politics. Handke considers it the task of the writer to distrust accepted ways of seeing the world, challenge public consensus and provide alternative images and perspectives. His biographically rooted emotional identification with Yugoslavia as a land of freedom, democratic equality and good living, contrasting with German and Austrian historical guilt, consumption and exploitation, led him to deny the right of the Slovenians to national self- determination in 1991, blame the Croatians and their international backers for the conflict in Bosnia which followed, insist that the Bosnian Serbs were not the only ones responsible for crimes against humanity, and defend Serbia and its President Slobodan Milošević during the Kosovo war at the end of the decade. My paper asks what Handke said about Yugoslavia, before going on to suggest why he said it, and consider what conclusions can be drawn about the part played by writers and intellectuals in shaping the collective memory of past events and directing collective understandings of the present. -

A Study of Early Anabaptism As Minority Religion in German Fiction

Heresy or Ideal Society? A Study of Early Anabaptism as Minority Religion in German Fiction DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ursula Berit Jany Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Advisor Professor Katra A. Byram Professor Anna Grotans Copyright by Ursula Berit Jany 2013 Abstract Anabaptism, a radical reform movement originating during the sixteenth-century European Reformation, sought to attain discipleship to Christ by a separation from the religious and worldly powers of early modern society. In my critical reading of the movement’s representations in German fiction dating from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, I explore how authors have fictionalized the religious minority, its commitment to particular theological and ethical aspects, its separation from society, and its experience of persecution. As part of my analysis, I trace the early historical development of the group and take inventory of its chief characteristics to observe which of these aspects are selected for portrayal in fictional texts. Within this research framework, my study investigates which social and religious principles drawn from historical accounts and sources influence the minority’s image as an ideal society, on the one hand, and its stigmatization as a heretical and seditious sect, on the other. As a result of this analysis, my study reveals authors’ underlying programmatic aims and ideological convictions cloaked by their literary articulations of conflict-laden encounters between society and the religious minority. -

Adolf Muschg: Ein Hase Mit Offenen Ohren Für Das Ungehörte Und Unerhörte

Adolf Muschg: Ein Hase mit offenen Ohren für das Ungehörte und Unerhörte Meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren, sehr geehrter Adolf Muschg, liebe Atsuko Muschg, Es ist mir eine Ehre, hier vor ihnen zu stehen, und es ist uns allen eine Ehre, dass Sie, wertes Publikum, so zahlreich erschienen sind, heute, wo in Zürich wieder so viel los ist, wo das Literaturhaus zum 20. Jubiläum seine Saison eröffnet, wo die Leute eine lange Nacht lang in die Museen schwärmen und in der Badi Enge ein Abend mit einer Synchronschwimm-Show veranstaltet wird. Nun, bei Synchronschwimmen sind Auftritte von Duetten, die ausschliesslich von Männern dargeboten werden, nicht unbedingt ein Renner. Vielleicht steigern wir heute ja, horribile dictu, die Quote dieser wenig beliebten Disziplin... Lassen wir also durch den Strom meiner Rede Adolf Muschg und Gottfried Keller in einem synchronen Duett schwimmen! (Und diese Synchronizität hat wahrlich nicht nur biografische Gründe, wie etwa den Umstand, dass Adolf Muschg mit einer Rede zu Keller jene Professur an der ETH für deutsche Literatur antrat, die Keller ausgeschlagen hatte, weil er, wie er seiner Mutter schrieb, lieber einen Posten hätte, „wo man nicht denken muss“. – Kann man sich Muschg eigentlich nicht denkend vorstellen?) Nun. Hier stehe ich also, und schwimme ein wenig: natürlich nicht als Elias Canetti, dem man mit Festvorträgen das Bild von Gottfried Keller so verhagelte, dass er in seinem jugendlichen und „unwissenden Hochmut“ als 14-jähriger zornig gelobte, nie ein Lokalschriftsteller wie Keller werden zu wollen, aber ich stehe hier und schwimme ein wenig, weil mir Keller in der Schule ebenfalls verhagelt wurde, weil vom Lehrer „Die drei Kammmacher“ und andere Novellen stets über den Kamm des gesunden Menschenverstandes gestrählt wurden. -

HILDEGARD EMMEL Der Weg in Die Gegenwart: Geschichte Des

Special Service ( 1973) is also his most popular dynamic movement that serves to acceler among readers of Spanish, probably be ate the flow of events and heighten ironic cause of its rollicking humor. Pantoja is a contrasts. diligent young army officer who, because of his exceptionally fine record as an ad In his dissection of Peruvian society, ministrator, is sent to Peru's northeastern Vargas Llosa satirizes the military organiza tropical region on a secret mission, the tion as well as the corruption, hypocrisy, purpose of which is to organize a squad and cliché-ridden language of his fellow ron of prostitutes referred to as "Special countrymen. A difficult book to trans Service." It seems that a series of rapes late, Captain Pantoja . loses some of has been committed by lonely soldiers its impact in the English version. Still, it stationed in this remote zone, and high- should be greatly enjoyed by American ranking officers in Lima reason that the readers with a taste for absurd humor prostitutes would satisfy sexual appetites and innovative narrative devices. and thus reduce tensions between civilians and military personnel. Although less than enthusiastic about his new post, Pantoja George R. McMurray flies to the tropical city of Iquitos where, despite many obstacles, he makes his unit the most efficient in the Peruvian army. Meanwhile, a spellbinding prophet called Brother Francisco has mesmerized a grow ing sect of religious fanatics, whose rituals include the crucifixion of animals and human beings. The novel is brought to a climax by the death of Pantoja's beautiful HILDEGARD EMMEL mistress, one of the prostitutes, and his Der Weg in die Gegenwart: Geschichte dramatic funeral oration revealing the des deutschen Romans. -

The Anarchists: a Picture of Civilization at the Close of the Nineteenth Century

John Henry Mackay The Anarchists: A Picture of Civilization at the Close of the Nineteenth Century 1891 The Anarchist Library Contents Translator’s Preface ......................... 3 Introduction.............................. 4 1 In the Heart of the World-Metropolis .............. 6 2 The Eleventh Hour.......................... 21 3 The Unemployed ........................... 35 4 Carrard Auban ............................ 51 5 The Champions of Liberty ..................... 65 6 The Empire of Hunger........................ 87 “Revenge! Revenge! Workingmen, to arms! . 112 “Your Brothers.” ...........................112 7 The Propaganda of Communism..................127 8 Trafalgar Square ...........................143 9 Anarchy.................................153 Appendix................................164 2 Translator’s Preface A large share of whatever of merit this translation may possess is due to Miss Sarah E. Holmes, who kindly gave me her assistance, which I wish to grate- fully acknowledge here. My thanks are also due to Mr. Tucker for valuable suggestions. G. S. 3 Introduction The work of art must speak for the artist who created it; the labor of the thoughtful student who stands back of it permits him to say what impelled him to give his thought voice. The subject of the work just finished requires me to accompany it with a few words. *** First of all, this: Let him who does not know me and who would, perhaps, in the following pages, look for such sensational disclosures as we see in those mendacious speculations upon the gullibility of the public from which the latter derives its sole knowledge of the Anarchistic movement, not take the trouble to read beyond the first page. In no other field of social life does there exist to-day a more lamentable confusion, a more naïve superficiality, a more portentous ignorance than in that of Anarchism. -

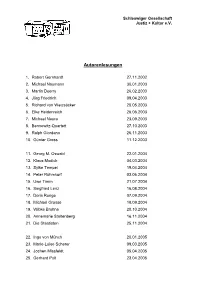

Der Präsident

Schleswiger Gesellschaft Justiz + Kultur e.V. Autorenlesungen 1. Robert Gernhardt 27.11.2002 2. Michael Naumann 30.01.2003 3. Martin Doerry 26.02.2003 4. Jörg Friedrich 09.04.2003 5. Richard von Weizsäcker 20.05.2003 6. Elke Heidenreich 26.06.2003 7. Michael Naura 23.09.2003 8. Bennewitz-Quartett 27.10.2003 9. Ralph Giordano 26.11.2003 10. Günter Grass 11.12.2003 11. Georg M. Oswald 22.01.2004 12. Klaus Modick 04.03.2004 13. Sylke Tempel 19.04.2004 14. Peter Rühmkorf 03.06.2004 15. Uwe Timm 21.07.2004 16. Siegfried Lenz 16.08.2004 17. Doris Runge 07.09.2004 18. Michael Grosse 18.09.2004 19. Wibke Bruhns 20.10.2004 20. Annemarie Stoltenberg 16.11.2004 21. Die Staatisten 25.11.2004 22. Ingo von Münch 20.01.2005 23. Marie-Luise Scherer 09.03.2005 24. Jochen Missfeldt 05.04.2005 25. Gerhard Polt 23.04.2005 2 26. Walter Kempowski 25.08.2005 27. F.C. Delius 15.09.2005 28. Herbert Rosendorfer 31.10.2005 29. Annemarie Stoltenberg 23.11.2005 30. Klaus Bednarz 08.12.2005 31. Doris Gercke 26.01.2006 32. Günter Kunert 01.03.2006 33. Irene Dische 24.04.2006 34. Mozartabend (Michael Grosse, „Richtertrio“) ´ 11.05.2006 35. Roger Willemsen 12.06.2006 36. Gerd Fuchs 28.06.2006 37. Feridun Zaimoglu 07.09.2006 38. Matthias Wegner 11.10.2006 39. Annemarie Stoltenberg 15.11.2006 40. Ralf Rothmann 07.12.2006 41. Bettina Röhl 25.01.2007 42. -

G.V. Plekhanov Anarchism and Socialism (1895)

G.V. Plekhanov Anarchism and Socialism (1895) 1 Anarchism and Socialism G.V. Plekhanov Halaman 2 Anarchism and Socialism . Publisher: New Times Socialist Publishing Co., Minneapolis 1895 Translated: Eleanor Marx Aveling Transcribed: Sally Ryan for marxists.org in 2000 Anarchism and Socialism G.V. Plekhanov Halaman 3 Table of Content Preface to the First English Edition by Eleanor Marx Aveling Chapter I. The Point of View of the Utopian Socialists Chapter II. The Point of View of Scientific Socialism Chapter III. The Historical Development of the Anarchist Doctrine Chapter IV. Proudhon Chapter V. Bakounine Chapter VI. Bakounine – (Concluded) Chapter VII. The Smaller Fry Chapter VIII. The So-called Anarchist Tactics Their Morality Chapter IX. Conclusion Anarchism and Socialism G.V. Plekhanov Halaman 4 Preface to the First English Edition The work of my friend George Plechanoff, Anarchism and Socialism, was written originally in French. It was then translated into German by Mrs. Bernstein, and issued in pamphlet form by the German Social-Democratic Publishing Office Vorwaerts . It was next translated by myself into English, and so much of the translation as exigencies of space would permit, published in the Weekly Times and Echo . As to the book itself. There are those who think that the precious time of so remarkable a writer, and profound a thinker as George Plechanoff is simply wasted in pricking Anarchist wind-bags. But, unfortunately, there are many of the younger, or of the more ignorant sort, who are inclined to take words for deeds, high-sounding phrases for acts, mere sound and fury for revolutionary activity, and who are too young or too ignorant to know that such sound and fury signify nothing.