Chapter 4 Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macmillan Dictionary Buzzword: Zonkey

TEACHER’S NOTES zonkey www.macmillandictionary.com Overview: Suggestions for using the Macmillan Dictionary BuzzWord article on zonkey and the associated worksheets Total time for worksheet activities: 45 minutes Suggested level: Upper intermediate and above 1. If you intend to use the worksheets in animal they are describing, e.g. ‘I have paws class, go to the BuzzWord article at the and whiskers, what am I?’ (= cat). web address given at the beginning of the 6. All the words for baby animals in Exercise worksheet and print off a copy of the article. 4 have entries in the Macmillan Dictionary. Make a copy of the worksheet and the Ask students to complete the exercise BuzzWord article for each student. You might individually, starting with the words they know find it helpful not to print a copy of the Key for and then looking up any unfamiliar ones as each student but to check the answers as necessary. Check answers as a class. a class. 7. Exercise 5 explores some common 2. If the members of your class all have internet conversational idioms based on animals. access, ask them to open the worksheet Explain to students that using idiomatic before they go to the Buzzword article link. phrases like these can make conversational Make sure they do not scroll down to the Key English sound more natural, but getting until they have completed each exercise. them wrong is a very obvious mistake! Ask 3. Encourage students to read through the students to complete the exercise in pairs. questions in Exercise 1 before they look Explain that if they need to use a dictionary at the BuzzWord article. -

Les Composés Coordinatifs En Anglais Contemporain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte a LUniversite Lyon 2 Les compos´escoordinatifs en anglais contemporain Vincent Renner To cite this version: Vincent Renner. Les compos´escoordinatifs en anglais contemporain. Linguistique. Universit´e Lumi`ere- Lyon II, 2006. Fran¸cais. <tel-00565046> HAL Id: tel-00565046 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00565046 Submitted on 10 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Université Lumière-Lyon 2 École doctorale Humanités et Sciences Humaines Centre de Recherches en Terminologie et Traduction Vincent Renner LES COMPOSÉS COORDINATIFS EN ANGLAIS CONTEMPORAIN Thèse préparée sous la direction de Monsieur Pierre Arnaud Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 13 octobre 2006 en vue de l’obtention du doctorat Lexicologie et Terminologie Multilingues et Traduction Jury : M. Pierre Arnaud, professeur à l’Université Lyon 2 (directeur) M. Nicolas Ballier, professeur à l’Université Paris 13 M. Laurie Bauer, professeur à l’Université Victoria de Wellington M. Henri Béjoint, professeur à l’Université Lyon 2 M. Claude Boisson, professeur à l’Université Lyon 2 M. Michel Paillard, professeur à l’Université de Poitiers (président) À Mamida, La linguistique a pour tâche d’apprivoiser le vocabulaire. -

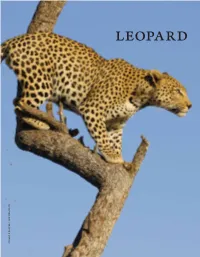

Leopard Stuart G Porter / Shutterstock G Porter Stuart נמר Leopard Namer

Leopard Stuart G Porter / Shutterstock G Porter Stuart נמר Leopard Namer The Leopards of Israel ִא ִּתי ִמ ְּל ָבנוֹן ַּכ ָּלה ִא ִּתי ִמ ְּל ָבנוֹן ָּת ִבוֹאי ָּתׁש ּוִרי ֵמרֹ ׁאש ֲא ָמ ָנה ֵמרֹ ׁאש NATURAL HISTORY ְׂש ִניר ְו ֶחְרמוֹן ִמ ְּמעֹנוֹת ֲאָריוֹת ֵמ ַהְרֵרי ְנ ֵמִרים׃ שיר השירים פרק ד The strikingly beautiful leopard is the most widespread of all the big cats. It lives in a variety of habitats in much of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. In former times, leop- be man-eaters in other parts of the world, and are hunted ards were abundant throughout Israel, especially in the as a result. In the first decade of the twentieth century, at hilly and mountainous regions: least five leopards were killed in between Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh; one of them badly mauled a person after With me from Lebanon, O bride, come with me from being shot.3 The last specimen was killed by a shepherd Lebanon, look from the peak of Amana, from the peak near Hanita in 1965.4 Another leopard subspecies that lived of Senir and Hermon, from the dens of lions, from the in the area was the Sinai leopard, Panthera pardus jarvus. It mountains of leopards. (Song. 4:8). was hunted by the Bedouin upon whose goats it preyed, The leopard of the mountains was the Anatolian leop- and is now extinct. ard, Panthera pardus tulliana, which was found in much of Today, the Arabian leopard, Panthera pardus nimr, is the hilly regions of Israel. After the 1834 Arab pogrom in the only subspecies of leopard to be found in Israel. -

Florida May 26, 1966 26 Pages PRICE 104 High Wins Local Precincts, M Cassady Takes Party Post Position in November, Neither Mitteewoman

WEI S-FILS • BOX 1678 Wet! Sr AUGU3TIHE FLA May 21-25, 1966 Hi Lo Rain Sat. 87 75 .07 Sun. 84 72 .65 Mon. 81 71 .66 Tues. 82 65 .45 Wed. noon 87 68 Edition 0 BOCA RATON Vol. U No. 54 Boca Raton, Florida May 26, 1966 26 Pages PRICE 104 High Wins Local Precincts, m Cassady Takes Party Post position in November, neither mitteewoman. Burdick was the press my deepest gratitude to all Though the gubernatorial race of the wonderful workers who may have been a bitter one he nor the GOP's Joseph South Florida coordinator for Humphrey are from the western Robert King-High's campaign. helped to win. With this kind of elsewhere in Florida, it at- enthusiasm, and the energetic tracted just over a third of the part of the county. William James, a Delray Beach insurance broker, was support of all the voters of Palm registered Democrats in Boca In the Democratic party of- Beach County, I look forward Raton Tuesday. fice races, Sylvan Burdick, the victorious GOP committee- man. to a clean sweep Republican The few who did go to the West Palm Beacji attorney and victory in November." polls gave Miami's Robert King sometime adult student at Flor- Mrs. Cassady, who was an ida Atlantic University, took enthusiastic campaigner, was High faces Republican Claude High 1,155 votes toGov. Haydon Kirk Jr. in November, Carter Burns' 646, High carried the the committeeman's post, while equally enthusiastic in victory. another attorney, Mrs,, Anita "A little bit humble, too," has no GOP opposition in the state by more than 80,000 to PSC race. -

Animal Kingdom

THE TORAH ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE ANIMAL KINGDOM Volume I: Wild Animals/ Chayos Sample Chapter: The Leopard RABBI NATAN SLIFKIN The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdomis a milestone in Jewish publish- ing. Complete with stunning, full-color photographs, the final work will span four volumes. The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom includes: • Entries on every mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, insect and fish found in the Torah, Prophets and Writings; • All scriptural citations, and a vast range of sources from the Talmud and Midrash; • Detailed analyses of the identities of these animals, based on classical Jewish sources and contemporary zoology; • The symbolism of these animals in Jewish thought throughout the ages; • Zoological information about these animals and fascinating facts; • Studies of man’s relationship with animals in Torah philosophy and law; • Lessons that Judaism derives from the animal kingdom for us to use in our own daily lives; • Laws relating to the various different animals. The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom is an essential reference work that will one day be commonplace in every home and educational institution. For more details, and to download this chapter, see www.zootorah.com/encyclopedia. Rabbi Natan Slifkin, the internationally renowned “Zoo Rabbi,” is a popular lec- turer and the author of numerous works on the topic of Judaism and the natural sciences. He has been passionately study- ing the animal kingdom his entire life, and began working on The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom over a decade ago. © Natan Slifkin 2011. This sample chapter may be freely distributed provided it is kept com- plete and intact. -

Tvorbeni Modeli Stopljenica U Hrvatskom Rječniku Stopljenica

Tvorbeni modeli stopljenica u hrvatskom rječniku stopljenica Ljutić, Anamarija Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:849283 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U RIJECI FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET Anamarija Ljutić Tvorbeni modeli stopljenica u Hrvatskom rječniku stopljenica (ZAVRŠNI RAD) Rijeka, 2020. SVEUČILIŠTE U RIJECI FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET Odsjek za kroatistiku Anamarija Ljutić Matični broj: 0009077968 Tvorbeni modeli stopljenica u Hrvatskom rječniku stopljenica ZAVRŠNI RAD Prediplomski studij: Hrvatski jezik i književnost Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Kristian Novak Rijeka, 11. rujna 2020. IZJAVA Kojom izjavljujem da sam završni rad naslova Tvorbeni modeli stopljenica u Hrvatskom rječniku stopljenica izradio/la samostalno pod mentorstvom izv. prof. dr. sc. Kristiana Novaka. U radu sam primijenio/la metodologiju znanstvenoistraživačkoga rada i koristio/la literaturu koja je navedena na kraju završnoga rada. Tuđe spoznaje, stavove, zaključke, teorije i zakonitosti koje sam izravno ili parafrazirajući naveo/la u diplomskom radu na uobičajen način citirao/la sam i povezao/la s korištenim bibliografskim jedinicama. Student/studentica -

GLOBALISTICS and GLOBALIZATION STUDIES Global Transformations and Global Future Leonid Grinin, Ilya Ilyin, Peter Herrmann, Andrey Korotayev

GLOBALISTICS AND GLOBALIZATION STUDIES Global Transformations and Global Future Leonid Grinin, Ilya Ilyin, Peter Herrmann, Andrey Korotayev To cite this version: Leonid Grinin, Ilya Ilyin, Peter Herrmann, Andrey Korotayev. GLOBALISTICS AND GLOBAL- IZATION STUDIES Global Transformations and Global Future. 2016, 978-5-7057-5026-9. hprints- 01794187 HAL Id: hprints-01794187 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-01794187 Submitted on 17 May 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LOMONOSOV MOSCOW STATE UNIVERSITY Faculty of Global Studies RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES The Eurasian Center for Big History and System Forecasting INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN STUDIES GLOBALISTICS AND GLOBALIZATION STUDIES Global Transformations and Global Future Edited by Leonid E. Grinin, Ilya V. Ilyin, Peter Herrmann, and Andrey V. Korotayev ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House Volgograd ББК 28.02 87.21 Globalistics and Globalization Studies: Global Transformations and Global Future. Yearbook / Edited by Leonid E. Grinin, Ilya V. Ilyin, Peter Herrmann, and Andrey V. Koro- tayev. – Volgograd: ‘Uchitel’ Publishing House, 2016. – 400 pp. The present volume is the fifth in the series of yearbooks with the title Globalistics and Globalization Studies. -

The Big Cats KIRTI BANSAL

FUN QUIZ the big cats KIRTI BANSAL 1. The Puma concolor is the largest wildcat in North America 3. A rare tiger subspecies that inhabits the Indonesian and has the largest range of any mammal in the western island. Smallest of all the tigers, these tigers rarely grow hemisphere. Secretive and largely solitary by nature, 2.5 meters in length. It is listed as a critically endangered this big cat is properly considered both nocturnal and species on the crepuscular. Some of its names are Puma, panther, cougar, IUCN Red List as painter, catamount, …………..etc. the population a. Mountain lion b. Barbary lion was estimated to c. Cape lion d. Masai lion be 400-500 in the wild. Threatened by deforestation and poaching, these tigers may have evolved to a smaller species due to its isolated island habitat, a process called insular dwarfi sm. a. Asian Lion b. Sumatran Tiger c. African Lion d. Siberian Tiger 4. Neofelis nebulosa is a wild cat occurring from 2. Classifi ed as endangered by the International Union for the Himalayan foothills through mainland Southeast Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, this big cat has Asia into China. It is an almost monkey like climber and suffered a substantial decline in its historic range due has been observed hanging from branches from its rear to rampant hunting in the 20th century. It is the fastest feet upside down. It has the longest upper canine teeth mammal on land, can reach speeds of 60-70 miles an hour. relative to skull size of any living carnivore. -

PDF EPUB} to Leave with the Reindeer by Olivia Rosenthal to Leave with the Reindeer

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} To Leave with the Reindeer by Olivia Rosenthal To Leave with the Reindeer. The world’s #1 eTextbook reader for students. VitalSource is the leading provider of online textbooks and course materials. More than 15 million users have used our Bookshelf platform over the past year to improve their learning experience and outcomes. With anytime, anywhere access and built-in tools like highlighters, flashcards, and study groups, it’s easy to see why so many students are going digital with Bookshelf. titles available from more than 1,000 publishers. customer reviews with an average rating of 9.5. digital pages viewed over the past 12 months. institutions using Bookshelf across 241 countries. To Leave with the Reindeer by Olivia Rosenthal and Publisher And Other Stories. Save up to 80% by choosing the eTextbook option for ISBN: 9781911508434, 1911508431. The print version of this textbook is ISBN: 9781911508434, 1911508431. To Leave with the Reindeer by Olivia Rosenthal and Publisher And Other Stories. Save up to 80% by choosing the eTextbook option for ISBN: 9781911508434, 1911508431. The print version of this textbook is ISBN: 9781911508434, 1911508431. To Leave with the Reindeer - Book. A woman challenges biology and convention in her struggle for freedom: a multi-voiced enquiry into the frontier between humans and animals. Language: English ISBN: 9781911508427 Publisher: Binding: Paperback Pages: 192 Published: April 18, 2019. Dimensions: 195x125x15 mm. Weight: 218 g. Price: £6.99 RRP: £8.99 You're saving: £2.00 ( 22% ) Shipping: £1.50. Delivery: 3-5 business days Expected delivery: June 23, 2021 Delivery within the UK Extended 30 days return policy. -

SCIENCE CHINA Research Advances in Animal Distant Hybridization

SCIENCE CHINA Life Sciences • REVIEW • September 2014 Vol.57 No.9: 889–902 doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4707-1 Research advances in animal distant hybridization ZHANG ZhuoHui†, CHEN Jie†, LI Ling, TAO Min, ZHANG Chun, QIN QinBo, XIAO Jun, LIU Yun & LIU ShaoJun* Key Laboratory of Protein Chemistry and Fish Developmental Biology of Ministry of Education, College of Life Sciences, Hunan Normal University, Changsha 410081, China Received February 17, 2014; accepted July 3, 2014; published online August 1, 2014 Distant hybridization refers to crosses between two different species or higher-ranking taxa that enables interspecific genome transfer and leads to changes in phenotypes and genotypes of the resulting progeny. If progeny derived from distant hybridiza- tion are bisexual and fertile, they can form a hybrid lineage through self-mating, with major implications for evolutionary bi- ology, genetics, and breeding. Here, we review and summarize the published literature, and present our results on fish distant hybridization. Relevant problems involving distant hybridization between orders, families, subfamilies, genera, and species of animals are introduced and discussed, with an additional focus on fish distant hybrid lineages, genetic variation, patterns, and applications. Our review serves as a useful reference for evolutionary biology research and animal genetic breeding. distant hybridization, lineage, tetraploid, triploid, genetic breeding, application Citation: Zhang ZH, Chen J, Li L, Tao M, Zhang C, Qin QB, Xiao J, Liu Y, Liu SJ. Research advances in animal distant hybridization. Sci China Life Sci, 2014, 57: 889–902, doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4707-1 Distant hybridization, defined as a cross between two dif- obtained by interspecific hybridization in plants, including ferent species or higher-ranking taxa, facilitates the transfer allotetraploid Raphano brassica formed by chromosome of genomes between species and gives rise to phenotypic doubling and allohexaploid Triticum aestivum generated by and genotypic changes in the resulting progeny. -

Thorns Also and Thistles

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 23/1 (2012):18-45. Article copyright © 2012 by Warren A. Shipton. Thorns Also and Thistles Warren A. Shipton Ellen G. White Heritage Research Centre Asia-Pacific International University, Thailand 1. Introduction The principles of God’s government were expressed in the beauties of His creation and the harmonious relationships which existed among His creatures (Gen 1:31; Isa 65:17-19, 24, 25; cf. Rev 21:3, 4, 8). There was one individual, however, who was determined to change all this. His dissatisfaction with God’s government commenced in heaven and progressed so that finally Lucifer found himself barred from its inner courts but with access to other parts of God’s created universe. Now we find that on earth he has despoiled that which was once perfect and good and thereby has added to the cup of human misery. In this article I examine the biblical record, selected evidences of science, and the resources of the Spirit of Prophecy in an attempt to answer some of the basic questions regarding the nature of selected curses proclaimed by God on the earth after the Fall. I attempt to reconstruct scenarios which help us to understand the intent of and methods used by Satan to deface and change nature and lead humanity to deface the image of God. This will help us to relate to events happening in the world around us in a more intelligent manner and will aid in understanding statements on amalgamation made by Ellen White. I will show that these statements are coherent and have deep meaning and relevance today. -

Post-Zoo Design: Alternative Futures in the Anthropocene

Post-Zoo Design: Alternative Futures in the Anthropocene by Rua Alshaheen A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Renata Hejduk, Chair Braden Allenby Ed Finn Darren Petrucci ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2019 ©2019 Rua Alshaheen All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Public awareness of nature and environmental issues has grown in the last decades and zoos have successfully followed suit by re-branding themselves as key representatives for conservation. However, considering the fast rate of environmental degradation, in the near future, zoos may become the only place left for wildlife. Some scholars argue that we have entered a new epoch titled the “Anthropocene” that postulates the idea that untouched pristine nature is almost nowhere to be found.1 Many scientists and scholars argue that it is time that we embraced this environmental situation and anticipated the change. 2 Clearly, the impact of urbanization is reaching into the wild, so how can we design for animals in our artificializing world? Using the Manoa School method that argues that every future includes these four, generic, alternatives: growth, discipline, collapse, and transformation3, this dissertation explores possible future animal archetypes by considering multiple possibilities of post zoo design. Keywords: Nature, Environment, Anthropocene, Zoo, Animal Design, Future, Scenario 1 Paul J. Crutzen, “Geology of Mankind,” Nature 415, no. 6867 (January 3, 2002): 23. 2 Jamie Lorimer, Wildlife in the Anthropocene (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Frank Oldfield et al., “The Anthropocene Review: Its Significance, Implications and the Rationale for a New Transdisciplinary Journal,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no.