Spill Prevention, Preparedness, and Response Program: Activity And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

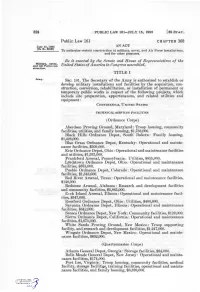

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Public Law 85-325-Feb

72 ST AT. ] PUBLIC LAW 85-325-FEB. 12, 1958 11 Public Law 85-325 AN ACT February 12, 1958 To authorize the Secretary of the Air Force to establish and develop certain [H. R. 9739] installations for'the national security, and to confer certain authority on the Secretary of Defense, and for other purposes. Be it enacted Ify the Senate and House of Representatives of the Air Force instal United States of America in Congress assembled^ That the Secretary lations. of the Air Force may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, converting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including site prep aration, appurtenances, utilities, and equipment, for the following projects: Provided^ That with respect to the authorizations pertaining to the dispersal of the Strategic Air Command Forces, no authoriza tion for any individual location shall be utilized unless the Secretary of the Air Force or his designee has first obtained, from the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, approval of such location for dispersal purposes. SEMIAUTOMATIC GROUND ENVIRONMENT SYSTEM (SAGE) Grand Forks Air Force Base, Grand Forks, North Dakota: Admin Post, p. 659. istrative facilities, $270,000. K. I. Sawyer Airport, Marquette, Michigan: Administrative facili ties, $277,000. Larson Air Force Base, Moses Lake, Washington: Utilities, $50,000. Luke Air Force Base, Phoenix, Arizona: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $11,582,000. Malmstrom Air Force Base, Great Falls, Montana: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $6,901,000. Minot Air Force Base, Minot, North Dakota: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $10,338,000. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Loan Act of 1933, As Amended; Making Appropriations for the Depart S

1955 .CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE 9249 ment of the Senate to the bill CH. R. ministering oaths and taking acknowledg Keller in ·behalf of physically handicapped 4904) to extend the Renegotiation Act ments by offi.cials of Federal penal and cor persons throughout ·the world. of 1951for2 years, and requesting a con rectional institutions; and H. R. 4954. An act to amend the Clayton The message also announced that the ference with the Senate on the disagree Act by granting a right of action to the Senate agrees to the amendments of the ing votes·of the two Houses thereon. United States to recover damages under the House to a joint resolution of the Sen Mr. BYRD. I move that the Senate antitrust laws, establishing a uniform ate of the following title: insist upon its amendment, agree to the statute of limitati9ns, and for other purposes. request of the House for a conference, S. J. Res. 67. Joint resolution to authorize The message also announced that the the Secretary of Commerce to sell certain and ~hat the Chair appoint the conferees Senate had passed bills and a concur vessels to citizens of the Republic of the on the part of the Senate. Philippines; to provide for the rehabilita The motion was agreed to; and the rent resolution of the following titles, in tion of the interisland commerce of the Acting President pro tempore appointed which the concurrence of the House is Philippines, and for other purposes. Mr. BYRD, Mr. GEORGE, Mr. KERR, Mr. requested: The message also announced that th~ MILLIKIN, and Mr. -

Calewg £Etteh International Headquarters — P

? j k JWinety - uAftnes. $nc. INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS cAlewg £etteh International Headquarters — P. 0. Box 1444 — Oklahoma City, Oklahoma AIR TERMINAL BUILDING — WILL ROGERS FIELD See You In Princeton July 13-14 President's Column THE NINETY - NINES ANNUAL CONVENTION Convention time again! This year to be in the lovely town of Princeton, NASSAU INN, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY New Jersey, registration on Friday, JULY 13 - 14 July the 13th, and business meeting on Saturday, July the 14th, with the July 13 a.m. Arrival from Wilmington and all points at Princeton banquet that night. And I have heard Fi'iday Airport. Transportation will be provided from here and that the speaker is—well, a flyer, au from bus or train depots. thor and world traveler, and not to be (Map of airport will be in your Reservation envelope) missed. I do hope that: every chapter chairman has sent the yearly report ALL 99'S MUST REGISTER! to her governor, and that every gover Registration fee $15.00, includes all activities listed above. nor plans to attend the Governors’ Separate tickets may be bought for 99 guests for theater, meeting on Friday at two o'clock, and luncheon or banquet. that every committee has a report ALL 99 DELEGATES REGISTER ON FRIDAY AT CREDENTIALS DESK ready to be presented at the meeting p.m. 1:30 2:30 3:30 Tour of Princeton University. on Saturday. This is a one hour walking tour of a famous and historic The past few weeks I have been campus. "out of this world" and “in the air". -

Washington National Guard Pamphlet

WASH ARNG PAM 870-1-7 WASH ANG PAM 210-1-7 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD PAMPHLET THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD VOLUME 7 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN POST WORLD WAR II HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DEPARTMENT STATE OF WASHINGTON OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL CAMP MURRAY, TACOMA, WASHINGTON 98430 - i - THIS VOLUME IS A TRUE COPY THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT ROSTERS HEREIN HAVE BEEN REVISED BUT ONLY TO PUT EACH UNIT, IF POSSIBLE, WHOLLY ON A SINGLE PAGE AND TO ALPHABETIZE THE PERSONNEL THEREIN DIGITIZED VERSION CREATED BY WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY - ii - INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME 7, HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD BY MAJOR GENERAL HOWARD SAMUEL McGEE, THE ADJUTANT GENERAL Volume 7 of the History of the Washington National Guard covers the Washington National Guard in the Post World War II period, which includes the conflict in Korea. This conflict has been categorized as a "police action", not a war, therefore little has been published by the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army or by individuals. However, the material available to our historian is believed to be of such importance as to justify its publication in this volume of our official history. While Washington National Guard units did not actually serve in Korea during this "police action", our Air National Guard and certain artillery units were inducted into service to replace like regular air and army units withdrawn for service in Korea. However, many Washington men participated in the action as did the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions, both of which had been stationed at Fort Lewis and other Washington military installations. -

Contents Academic Calendar

Contents Academic Calendar ...........................................................................................................................................................2 Academic Information ....................................................................................................................................................21 Accreditation .....................................................................................................................................................................5 Admissions ......................................................................................................................................................................6 Board of Trustees ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Course Description ..........................................................................................................................................................80 Degrees and Certificates .................................................................................................................................................26 Educational Programs .....................................................................................................................................................33 Faculty and Administrators ...........................................................................................................................................122 -

166 Public Law 86-500-.June 8, 1960 [74 Stat

166 PUBLIC LAW 86-500-.JUNE 8, 1960 [74 STAT. Public Law 86-500 June 8. 1960 AN ACT [H» R. 10777] To authorize certain construction at military installation!^, and for other pnriwses. He it enacted hy the Hemite and House of Representatives of the 8tfiction^'Acf°^ I'raited States of America in Congress assemoJed, I960. TITLE I ''^^^* SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, con- \'erting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including site preparation, appurtenances, utilities, and equip ment, for the following projects: INSIDE THE UNITED STATES I'ECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Training facilities, medical facilities, and utilities, $6,221,000. Benicia Arsenal, California: Utilities, $337,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Utilities and ground improvements, $353,000. Picatinny Arsenal, New Jersey: Research, development, and test facilities, $850,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, Colorado: Operational facilities, $369,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Community facilities and utilities, $1,000,000. Umatilla Ordnance Depot, Oregon: Utilities and ground improve ments, $319,000. Watertow^n Arsenal, Massachusetts: Research, development, and test facilities, $1,849,000. White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico: Operational facilities and utilities, $1,2'33,000. (Quartermaster Corps) Fort Lee, Virginia: Administrative facilities and utilities, $577,000. Atlanta General Depot, Georgia: Maintenance facilities, $365,000. New Cumberland General Depot, Pennsylvania: Operational facili ties, $89,000. Richmond Quartermaster Depot, Virginia: Administrative facili ties, $478,000. Sharpe General Depot, California: Maintenance facilities, $218,000. (Chemical Corps) Army Chemical Center, Maryland: Operational facilities and com munity facilities, $843,000. -

The News-Sentinel 1965

The News-Sentinel 1965 Saturday, January 2, 1965 Coy Lee Clemons Funeral services will be at 2 p.m. Sunday in the McCain Country Chapel at U.S. 31 and Ind. 16 for Coy Lee CLEMONS, 51, R.R. 1, Macy, who died at 4 a.m. Friday in his home following a six-year illness. Born in Smithville, Tenn., on May 7, 1913, he was the son of Charlie and Minnie CLEMONS. He was married Jan. 1, 1934, to Allie HALE, who survives. Mr. Clemons was a farmer and had lived in the Macy and Deedsville areas for the past 31 years. Surviving with the wife are the mother, Deedsville; three sons, Robert [CLEMONS], Denver; Carl Dee [CLEMONS], at home, and Bobbie Joe [CLEMONS], Akron; two daughters, Mrs. Barbara RIFFET, Rochester, and Mrs. Reba GARRISON, R.R. 3, Peru; three brothers, Woodrow [CLEMONS], Peru, and Eskel and Frank [CLEMONS] both Deedsville; four sisters, Mrs. Maggie WHITTENBERGER and Mrs. Jean FITZPATRICK, both Macy, and Mrs. Vernie DILLMAN and Mrs. Marion COOK, both Peru, and several grandchildren. The Rev. E. C. CLARK will officiate at the services. Friends may call at the funeral home. Catherine Caughell Mrs. Catherine CAUGHELL, 94, who had been a patient in a nursing home here, died at 5 a.m. Friday in South Bend Memorial hospital. Surviving are two sons and three daughters. Last rites will be at 2 p.m. Sunday at the Miller funeral home in Monticello and burial will be in the Cedarville cemetery 10 miles southeast of Monticello in Carroll county. Dr. -

PORT of MOSES LAKE Comprehensive Scheme of Harbor Improvements

ne PORT OF MOSES LAKE Comprehensive Scheme of Harbor Improvements Final August 30, 2019 BST Associates Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................................................................... i Figures ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... ii Tables ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1. Overview of the Port ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Mission Statement ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Role of the Port ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Strategic Plan Goals ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Accomplishments of the Port .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Connecting the World 22 Kofi Amoo-Gottfried ’01 Steers Facebook’S Consumer Marketing

MACALESTER 2017 FALL TODAY CONNECTING THE WORLD Kofi Amoo-Gottfried’s rise at Facebook is fueled by a passion for broadening access to the internet. PAGE 22 MACALESTER TODAY FALL 2017 10 12 16 FEATURES Prolific Producer 10 Making the Most of Your Roy Gabay ’85 brings plays to Money 26 life—both on and off Broadway. Alumni experts offer advice on managing your money and Theatrical Revival 12 planning for the future. By early 2019, Mac will have a new home for the performing arts. Learning from Notorious RBG 32 Golden Scots 16 Beth Neitzel ’03 on her recent They knew Macalester during clerkship with U.S. Supreme Court the Great Depression and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg World War II. Where did life take these alumni? Connecting the World 22 Kofi Amoo-Gottfried ’01 steers Facebook’s consumer marketing. ON THE COVER: Kofi Amoo-Gottfried ’01 Photo by Robert Houser STAFF EDITOR Rebecca DeJarlais Ortiz ’06 [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Brian Donahue CLASS NOTES EDITOR Robert Kerr ’92 PHOTOGRAPHER David J. Turner CONTRIBUTING WRITER Jan Shaw-Flamm ’76 ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT FOR MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Julie Hurbanis 22 32 CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jerry Crawford ’71 PRESIDENT DEPARTMENTS Brian Rosenberg VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT Letters 2 D. Andrew Brown Household Words 3 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI ENGAGEMENT 1600 Grand 4 Katie Ladas Class of 2021, astronomy MACALESTER TODAY (Volume 105, Number 4) prodigies, and a historic is published by Macalester College. It is mailed free of charge to alumni and friends baseball season of the college four times a year. -

Air Washington

AIR WASHINGTON About the author In 2010, unemployment in Washington State hit Jim Kershner is the author of four a Great Recession high of 10.4 percent. Yet the Boeing previous books, including Carl Company was having trouble finding skilled workers Maxey: A Fighting Life (University Most of the eleven colleges participating to build its planes, including the revolutionary new of Washington Press), which was in the Air Washington consortium already had 787 Dreamliner. Several of the state’s community a finalist for the Washington State aerospace programs of their own, but winning college presidents began looking for ways to address Book Award in 2009. He has written a $20 million federal grant allowed them to this economic disconnect. One of them, Joe Dunlap of more than 190 historical essays for expand their programs, purchase new equipment, Spokane Community College, found a possible solution HistoryLink.org, The Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, where he is a staff historian. His forty-year including airplanes, and hire more instructors. The in Washington, D.C., where the U.S. Department of journalism career includes 22 years as a columnist and colleges also cooperated to align their program Labor was preparing to distribute $2 billion in grants for reporter for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane. He has offerings, making it easy for students to move Creating Careers in Aerospace Creating Careers in Aerospace workforce education and retraining as part of President won seven awards from the National Society of Newspaper from one college to another. Barack Obama’s economic stimulus program. Dunlap Columnists.