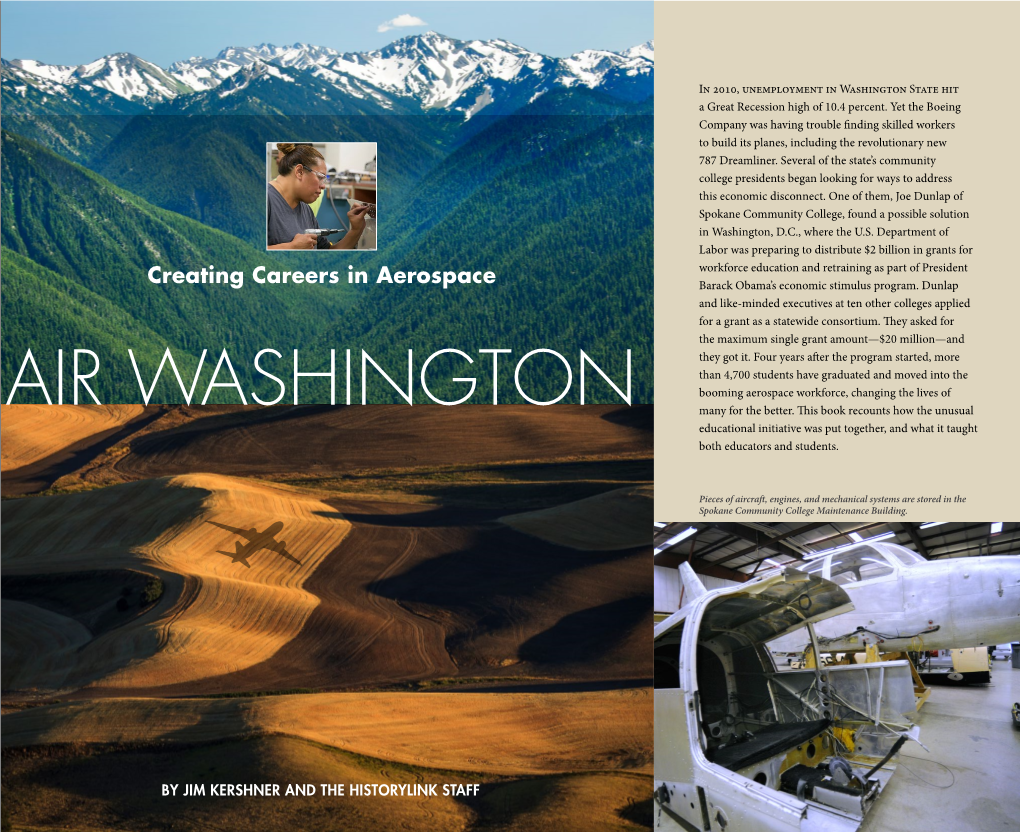

Air Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Regulamento (Ue) N

11.2.2012 PT Jornal Oficial da União Europeia L 39/1 II (Atos não legislativos) REGULAMENTOS o REGULAMENTO (UE) N. 100/2012 DA COMISSÃO de 3 de fevereiro de 2012 o que altera o Regulamento (CE) n. 748/2009, relativo à lista de operadores de aeronaves que realizaram uma das atividades de aviação enumeradas no anexo I da Diretiva 2003/87/CE em ou após 1 de janeiro de 2006, inclusive, com indicação do Estado-Membro responsável em relação a cada operador de aeronave, tendo igualmente em conta a expansão do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União aos países EEE-EFTA (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) A COMISSÃO EUROPEIA, 2003/87/CE e é independente da inclusão na lista de operadores de aeronaves estabelecida pela Comissão por o o força do artigo 18. -A, n. 3, da diretiva. Tendo em conta o Tratado sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia, (5) A Diretiva 2008/101/CE foi incorporada no Acordo so bre o Espaço Económico Europeu pela Decisão o Tendo em conta a Diretiva 2003/87/CE do Parlamento Europeu n. 6/2011 do Comité Misto do EEE, de 1 de abril de e do Conselho, de 13 de Outubro de 2003, relativa à criação de 2011, que altera o anexo XX (Ambiente) do Acordo um regime de comércio de licenças de emissão de gases com EEE ( 4). efeito de estufa na Comunidade e que altera a Diretiva 96/61/CE o o do Conselho ( 1), nomeadamente o artigo 18. -A, n. 3, alínea a), (6) A extensão das disposições do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União, no setor da aviação, aos Considerando o seguinte: países EEE-EFTA implica que os critérios fixados nos o o termos do artigo 18. -

KFP067 22Gb.Pdf

, , , " beginning as "The Boe ing Clipper". the opment of Model 294, the Air Corps "Pro word was not a Boeing model name like ject X" that was to become the XB-15, "Flying Fortress" (Model 299) or "Strat the Model 299 that was the ill-fated proto oliner" (Model 307). The word "Clipper", type of the B-17, and was cu rrently con made famous by the famous line of fast, tinuing XB-15 work and redesigning the square-rigged sailing ships developed by B-17 for production when the Pan Am re Donald McKay in the late 1840s, was ac quest was received on February 28, 1936. tually owned by Pan Ameri ca n. After ap With so much already in the works, it wa s The Boeing 314 Clipper was a marvelous machine plying it as part of the names on individ felt that the company couldn't divert the even by today's standards. She was big, comfort· ual airplanes, as "China Clipper", "Clip engineering manpower needed for still a able and very dependable. At 84,000 Ibs. gross per America", etc., the airline got a copy nother big project. weight, with 10 degrees of flap and no wind, she right on the word and subsequently be The deadline for response had passed used 3,200 ft. to take off, leaving the water in 47 came very possessive over its use. I t is re when Wellwood E. Beall, an engineer di seconds. At 70,000 Ibs. with 20 degrees of flap ported to have had injuncions issued verted to sa les and service work , returned and a30 knot headwind, she was off in just 240 h., against Packard for use of the work " Clip from a trip to Ch ina to deliver 10 Boeing leaving the water in only eight seconds. -

Cpnews May 2015.Pmd

CLIPPERCLIPPER PIONEERS,PIONEERS, INC.INC. FFORMERORMER PPANAN AAMM CCOCKPITOCKPIT CCREWREW PRESIDENT VICE-PRESIDENT & SECRETARY TREASURER / EDITOR HARVEY BENEFIELD STU ARCHER JERRY HOLMES 1261 ALGARDI AVE 7340 SW 132 ST 192 FOURSOME DRIVE CORAL GABLES, FL 33146-1107 MIAMI, FL 33156-6804 SEQUIM, WA 98382 (305) 665-6384 (305) 238-0911 (360) 681-0567 May 2015 - Clipper Pioneers Newsletter Vol 50-5 Page 1 The end of an Icon: A Boeing B-314 Flying Boat Pan American NC18601 - the Honolulu Clipper by Robert A. Bogash (www.rbogash.com/B314.html) In the world of man-made objects, be they antique cars, historic locomotives, steamships, religious symbols, or, in this case - beautiful airplanes, certain creations stand out. Whether due to perceived beauty, historical importance, or imagined romance, these products of man’s mind and hands have achieved a status above and beyond their peers. For me, the Lockheed Super Constellation is one such object. So is the Boeing 314 Flying Boat the Clipper, (when flown by Pan American Airways) - an Icon in the purest sense of the word. The B-314 was the largest, most luxurious, longest ranged commercial flying boat - built for, and operated by Pan Am. It literally spanned the world, crossing oceans and continents in a style still impressive today. From the late 1930’s through the Second World War, these sky giants set standard unequalled to this day. Arriving from San Francisco at her namesake city, the Honolulu Clipper disembarks her happy travelers at the Pearl City terminal. The 2400 mile trip generally took between 16 and 20 hours depending upon winds. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Seite Seite Vorwort 7 44 Witteman-Lewis XNBL-1 "Barling Bomber" 86 Einführung 9 45 Breda A5 oder BA 5 88 Geschichtlicher Überblick 10 46 Farman F.121 oder F-3X "Jabiru" 89 Die Entwicklung der wichtigsten Merkmale 16 47 Farman F-4 S 90 Die Flugzeugtypen 23 - 490 48 Latham HB-5 91 1 Sikorskij "Bolshoi Bal'tiskii" und "Russki 49 Bldriot 105 92 Witjas" 23 50 Schneider 400 93 2 Sikorskij "llja Muromez" 24 51 Caproni Ca 66 95 3 VGO.I, VGO.II, VGO.III, Staaken R.IV, R.V 52 Piaggio BN2 96 und R.VII 27 53 Breda A3 96 4 SSWR.I 30 54 Farman F.140 BN4 "Supergoliath" 98 5 Voisin "Triplan No 1" 32 55 Piaggio P.3 99 6 SSW R.ll, R.lll, R.IV, R.V, R.VI und R.VII 33 56 Blackburn "Iris" und "Perth" 100 7 Dornier Rs.l 35 57 Pentamoteur Richard-Penhoet 102 8 DaimlerR.lundR.il 37 58 Short "Singapore", "Calcutta" und 9 SSW Forssman R 38 "Rangoon" 103 10 DornierRs.il 39 59 Latham E-5 106 11 DFWR.I 41 60 Latäcoere 24 107 12 Staaken R.VI und Staaken L 42 61 Caproni Ca 75Qd "Polonia" 108 13 Curtiss-Wanamaker "Triplane" 44 62 Beardmore "Inflexible" 109 14 Linke-Hofmann R.l 45 63 Dornier Do R4 "Superwal" 110 15 DFWR.II 47 64 Rohrbach "Romar" 112 16 Dornier Rs.l II 48 65 Dornier DoX 113 17 Kennedy "Giant" 49 66 Junkers G 38 und K 51 115 18 Staaken R.XIV, R.XIVa und R.XV 50 67 Caproni Ca 90 118 19 Handley Page V/1500 52 68 Fokker F.XXXII "Universal" 119 20 AEG R.l 54 69 Dornier Do P 121 21 Staaken 8301 und 8303 55 70 Dornier DoS (Has) 122 22 Bristol "Braemar" und "Pullmann" 56 71 Handley-Page H.P.42 124 23 Navy/Curtiss NC Boats 58 72 Tupolew ANT-6 -

Pan Am's Historic Contributions to Aircraft Cabin Design

German Aerospace Society, Hamburg Branch Hamburg Aerospace Lecture Series Dieter Scholz Pan Am's Historic Contributions to Aircraft Cabin Design Based on a Lecture Given by Matthias C. Hühne on 2017-05-18 at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences 2017-11-30 2 Abstract The report summarizes groundbreaking aircraft cabin developments at Pan American World Airways (Pan Am). The founder and chief executive Juan Terry Trippe (1899-1981) estab- lished Pan Am as the world's first truly global airline. With Trippe's determination, foresight, and strategic brilliance the company accomplished many pioneering firsts – many also in air- craft cabin design. In 1933 Pan Am approached the industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958). The idea was to create the interior design of the Martin M-130 flying boat by a specialized design firm. Noise absorption was optimized. Fresh air was brought to an agreea- ble temperature before it was pumped into the aircraft. Adjustable curtains at the windows made it possible to regulate the amount of light in the compartments. A compact galley was designed. The cabin layout optimized seating comfort and facilitated conversion to the night setting. The pre-war interior design of the Boeing 314 flying boat featured modern contours and colors. Meals were still prepared before flight and kept warm in the plane's galley. The innovative post-war land based Boeing 377 Stratocruiser had a pressurized cabin. The cabin was not divided anymore into compartments. Seats were reclining. The galley was well equipped. The jet age started at Pan Am with the DC-8 and the B707. -

Check-In Am Bahnhof Und Fly Rail Baggage

1/8 Check-in am Bahnhof via Zürich und Genève Check-in à la gare via Zürich et Genève Check-in alla stazione via Zürich e Genève Check-in at the railstation via Zürich and Genève Version: 26. Januar 2011 Legend HA = Handlingagent SP = Swissport, DN = Dnata Switzerland AG, AS = Airline Assistance Switzerland AG, EH = Own Handling R = Reason T = Technical, S = Security, O = Other reason WT = Weight Tolerance Y = Economy-Class, C = Business-Class, F = First-Class * = Agent Informations Infoportal/Airlines Check-in ok Restrictions Airline, Code Check-in Einschränkungen/Restrictions WT HA R Y = 2 Adria Airways JP ok SP C = 3 Aegean Airlines A3 ok 2 SP Aer Lingus EI no SP O Aeroflot Russian Airlines SU no SP S Aerolineas Argentinas AR ok 2 SP African Safari Airways ASA ok 2 DN Afriqiyah Airways 8U no DN O Air Algérie* AH ok No boardingpass 0 SP Air Baltic BT no SP T Not for USA, Canada, Pristina, Russia, Air Berlin* AB ok Cyprus; 0 DN not possible for groups 11+ Air Cairo MSC ok 2 SP AC 6821 / 6822 / 6826 / 6829 / 6832 / Air Canada AC no SP T =ok Air Dolomiti EN ok 2 SP Air Europa AEA / UX ok 2 DN Not from Zürich; not for USA, Canada, AF ok* 2 SP T Air France* Mexico; no boardingpass Air India AI ok 2 SP Air Italy I9 ok 2 DN Air Mali XG no SP O Air Malta KM ok 3 SP Y = 7 Air Mauritius MK ok Not from Zurich SP C = 10 Air Mediteranée BIE ok 2 DN Air New Zealand NZ ok 2 SP Air One AP ok 2 SP Air Seychelles HM ok Not from Zurich 3 SP Air Transat TS ok 2 SP Alitalia AZ no SP/DN T American Airlines AA no SP T ANA All Nippon Airways NH ok 2 SP Armavia -

Change 3, FAA Order 7340.2A Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.2A CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2A, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. July 29, 2010. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Changes, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. Y[fa\.Uj-Koef p^/2, Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: k/^///V/<+///0 Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 7/29/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 4/8/10 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 7/29/10 1−1−1 . 8/27/09 1−1−1 . 7/29/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 4/8/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 7/29/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−23 . -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection Kristine L. Kaske; revised 2008 by Melissa A. N. Keiser 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Black and White Negatives....................................................................... 4 Series 2: Color Transparencies.............................................................................. 62 Series 3: Glass Plate Negatives............................................................................ 84 Series : Medium-Format Black-and-White and Color Film, circa 1950-1965.......... 93