The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

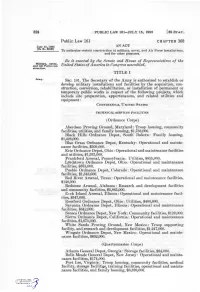

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

1 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the WESTERN DISTRICT of TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JOHN A. PATTERSON, Et Al., ) ) Plai

Case 5:17-cv-00467-XR Document 63-3 Filed 04/22/19 Page 1 of 132 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JOHN A. PATTERSON, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 5:17-CV-00467 ) DEFENSE POW/MIA ACCOUNTING ) AGENCY, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) THIRD DECLARATION OF GREGORY J. KUPSKY I, Dr. Gregory J. Kupsky, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746, declare as follows: 1. I am currently a historian in the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s (DPAA) Indo-Pacific Directorate, and have served in that position since January 2017. Among other things, I am responsible for coordinating Directorate manning and case file preparation for Family Update conferences, and I am the lead historian for all research and casework on missing servicemembers from the Philippines. I also conduct archival research in the Washington, D.C. area to support DPAA’s Hawaii-based operations. 2. The statements contained in this declaration are based on my personal knowledge and DPAA records and information made available to me in my official capacity. Qualifications 3. I have been employed by DPAA or one of its predecessor organizations, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), since May 2011. I served as a historian for JPAC from May 2011 to July 2014, and was the research lead for the Philippines, making numerous 1 Case 5:17-cv-00467-XR Document 63-3 Filed 04/22/19 Page 2 of 132 trips to the Philippines to coordinate with government officials, conduct research and witness interviews, and survey possible burial and aircraft crash sites, along with investigations and trips to other countries. -

Public Law 85-325-Feb

72 ST AT. ] PUBLIC LAW 85-325-FEB. 12, 1958 11 Public Law 85-325 AN ACT February 12, 1958 To authorize the Secretary of the Air Force to establish and develop certain [H. R. 9739] installations for'the national security, and to confer certain authority on the Secretary of Defense, and for other purposes. Be it enacted Ify the Senate and House of Representatives of the Air Force instal United States of America in Congress assembled^ That the Secretary lations. of the Air Force may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, converting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including site prep aration, appurtenances, utilities, and equipment, for the following projects: Provided^ That with respect to the authorizations pertaining to the dispersal of the Strategic Air Command Forces, no authoriza tion for any individual location shall be utilized unless the Secretary of the Air Force or his designee has first obtained, from the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, approval of such location for dispersal purposes. SEMIAUTOMATIC GROUND ENVIRONMENT SYSTEM (SAGE) Grand Forks Air Force Base, Grand Forks, North Dakota: Admin Post, p. 659. istrative facilities, $270,000. K. I. Sawyer Airport, Marquette, Michigan: Administrative facili ties, $277,000. Larson Air Force Base, Moses Lake, Washington: Utilities, $50,000. Luke Air Force Base, Phoenix, Arizona: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $11,582,000. Malmstrom Air Force Base, Great Falls, Montana: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $6,901,000. Minot Air Force Base, Minot, North Dakota: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $10,338,000. -

Company C, 194Th Tank Battalion, Dedicated on August 15, 1896 and Housed the Were Liberated from Japanese Prison Camps

News from The Monterey County Historical Society October 2004 A History of the Salinas National Guard Company 1895-1995 by Burton Anderson It has been 50 years since the surviving Lieutenant E.W. Winham. The armory was members of Company C, 194th Tank Battalion, dedicated on August 15, 1896 and housed the were liberated from Japanese prison camps. In company’s equipment including supplies, am- honor of those indomitable men, I am writing a munition and its single shot Springfield 45-70 three-part history of the company in peace and carbines left over from the Indian Wars. war. It is also a tribute to those fallen Company Other than routine training with its horses, C tankers who died during World War II in the the troop wasn’t called into active duty until service of their country; in combat and their April 1906, after the San Francisco earthquake, brutal prisoner of war ordeal. when it was deployed to the city and The Salinas company was organized as bivouacked in Golden Gate Park. The troop fa- Troop C, Cavalry, National Guard of California cilitated law and order in the devastated area for on August 5, 1895. It was the first guard unit formed in the Central Coast region and was headquartered in the new brick ar- mory at the corner of Salinas and Al- isal Streets in Sali- nas, California. The commanding officer was Captain Michael J. Burke, assisted by 1st Lieu- tenant J.L. Mat- thews and 2nd Founded December 22, 1933. Incorporated 1955. P.O. Box 3576, Salinas, CA 93912. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Loan Act of 1933, As Amended; Making Appropriations for the Depart S

1955 .CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE 9249 ment of the Senate to the bill CH. R. ministering oaths and taking acknowledg Keller in ·behalf of physically handicapped 4904) to extend the Renegotiation Act ments by offi.cials of Federal penal and cor persons throughout ·the world. of 1951for2 years, and requesting a con rectional institutions; and H. R. 4954. An act to amend the Clayton The message also announced that the ference with the Senate on the disagree Act by granting a right of action to the Senate agrees to the amendments of the ing votes·of the two Houses thereon. United States to recover damages under the House to a joint resolution of the Sen Mr. BYRD. I move that the Senate antitrust laws, establishing a uniform ate of the following title: insist upon its amendment, agree to the statute of limitati9ns, and for other purposes. request of the House for a conference, S. J. Res. 67. Joint resolution to authorize The message also announced that the the Secretary of Commerce to sell certain and ~hat the Chair appoint the conferees Senate had passed bills and a concur vessels to citizens of the Republic of the on the part of the Senate. Philippines; to provide for the rehabilita The motion was agreed to; and the rent resolution of the following titles, in tion of the interisland commerce of the Acting President pro tempore appointed which the concurrence of the House is Philippines, and for other purposes. Mr. BYRD, Mr. GEORGE, Mr. KERR, Mr. requested: The message also announced that th~ MILLIKIN, and Mr. -

Calewg £Etteh International Headquarters — P

? j k JWinety - uAftnes. $nc. INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS cAlewg £etteh International Headquarters — P. 0. Box 1444 — Oklahoma City, Oklahoma AIR TERMINAL BUILDING — WILL ROGERS FIELD See You In Princeton July 13-14 President's Column THE NINETY - NINES ANNUAL CONVENTION Convention time again! This year to be in the lovely town of Princeton, NASSAU INN, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY New Jersey, registration on Friday, JULY 13 - 14 July the 13th, and business meeting on Saturday, July the 14th, with the July 13 a.m. Arrival from Wilmington and all points at Princeton banquet that night. And I have heard Fi'iday Airport. Transportation will be provided from here and that the speaker is—well, a flyer, au from bus or train depots. thor and world traveler, and not to be (Map of airport will be in your Reservation envelope) missed. I do hope that: every chapter chairman has sent the yearly report ALL 99'S MUST REGISTER! to her governor, and that every gover Registration fee $15.00, includes all activities listed above. nor plans to attend the Governors’ Separate tickets may be bought for 99 guests for theater, meeting on Friday at two o'clock, and luncheon or banquet. that every committee has a report ALL 99 DELEGATES REGISTER ON FRIDAY AT CREDENTIALS DESK ready to be presented at the meeting p.m. 1:30 2:30 3:30 Tour of Princeton University. on Saturday. This is a one hour walking tour of a famous and historic The past few weeks I have been campus. "out of this world" and “in the air". -

Washington National Guard Pamphlet

WASH ARNG PAM 870-1-7 WASH ANG PAM 210-1-7 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD PAMPHLET THE OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD VOLUME 7 WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD IN POST WORLD WAR II HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DEPARTMENT STATE OF WASHINGTON OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL CAMP MURRAY, TACOMA, WASHINGTON 98430 - i - THIS VOLUME IS A TRUE COPY THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT ROSTERS HEREIN HAVE BEEN REVISED BUT ONLY TO PUT EACH UNIT, IF POSSIBLE, WHOLLY ON A SINGLE PAGE AND TO ALPHABETIZE THE PERSONNEL THEREIN DIGITIZED VERSION CREATED BY WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY - ii - INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME 7, HISTORY OF THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL GUARD BY MAJOR GENERAL HOWARD SAMUEL McGEE, THE ADJUTANT GENERAL Volume 7 of the History of the Washington National Guard covers the Washington National Guard in the Post World War II period, which includes the conflict in Korea. This conflict has been categorized as a "police action", not a war, therefore little has been published by the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army or by individuals. However, the material available to our historian is believed to be of such importance as to justify its publication in this volume of our official history. While Washington National Guard units did not actually serve in Korea during this "police action", our Air National Guard and certain artillery units were inducted into service to replace like regular air and army units withdrawn for service in Korea. However, many Washington men participated in the action as did the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions, both of which had been stationed at Fort Lewis and other Washington military installations. -

Seventieth Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of The

SEVENTIETH ANNUAL REPORT of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York June 10, 1939 Printed by The Moore Printing Company, Inc. Newburgh, N. Y. I 3s ©s\ OS Thi Ba > X m N a,CO 0 t j'cl *vt COos X C<3 +-a s +> a3 t 03k t N 8) i' > CO *i ° O X, ; D^3 Z X e ..g t <a t G) Address of President Franklin D. Roosevelt To the Graduating Class of the United States Military Academy, West Point, N. Y., June 12, 1939. MR. SUPERINTENDENT, FELLOW OFFICERS: L TAKE pleasure in greeting you as colleagues in the Service of the United States. You will find, as I have, that that Service never ends-in the sense that it engages the best of your ability and the best of your imagination in the endless adventure of keeping the United States safe, strong and at peace. You will find that the technique you acquired can be used in many ways, for the Army of the United States has a record of achievement in peace as well as in war. It is a little-appreciated fact that its con- structive activities have saved more lives through its peace time work and have created more wealth and well-being through its technical operations, than it has destroyed during its wars, hard-fought and victorious though they have been. With us the army does not stand for aggression, domination, or fear. It has become a corps d'elite of highly trained men whose tal- ent is great technical skill, whose training is highly cooperative, and whose capacity is used to defend the country with force when affairs require that force be used. -

Contents Academic Calendar

Contents Academic Calendar ...........................................................................................................................................................2 Academic Information ....................................................................................................................................................21 Accreditation .....................................................................................................................................................................5 Admissions ......................................................................................................................................................................6 Board of Trustees ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Course Description ..........................................................................................................................................................80 Degrees and Certificates .................................................................................................................................................26 Educational Programs .....................................................................................................................................................33 Faculty and Administrators ...........................................................................................................................................122 -

166 Public Law 86-500-.June 8, 1960 [74 Stat

166 PUBLIC LAW 86-500-.JUNE 8, 1960 [74 STAT. Public Law 86-500 June 8. 1960 AN ACT [H» R. 10777] To authorize certain construction at military installation!^, and for other pnriwses. He it enacted hy the Hemite and House of Representatives of the 8tfiction^'Acf°^ I'raited States of America in Congress assemoJed, I960. TITLE I ''^^^* SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, con- \'erting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including site preparation, appurtenances, utilities, and equip ment, for the following projects: INSIDE THE UNITED STATES I'ECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Training facilities, medical facilities, and utilities, $6,221,000. Benicia Arsenal, California: Utilities, $337,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Utilities and ground improvements, $353,000. Picatinny Arsenal, New Jersey: Research, development, and test facilities, $850,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, Colorado: Operational facilities, $369,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Community facilities and utilities, $1,000,000. Umatilla Ordnance Depot, Oregon: Utilities and ground improve ments, $319,000. Watertow^n Arsenal, Massachusetts: Research, development, and test facilities, $1,849,000. White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico: Operational facilities and utilities, $1,2'33,000. (Quartermaster Corps) Fort Lee, Virginia: Administrative facilities and utilities, $577,000. Atlanta General Depot, Georgia: Maintenance facilities, $365,000. New Cumberland General Depot, Pennsylvania: Operational facili ties, $89,000. Richmond Quartermaster Depot, Virginia: Administrative facili ties, $478,000. Sharpe General Depot, California: Maintenance facilities, $218,000. (Chemical Corps) Army Chemical Center, Maryland: Operational facilities and com munity facilities, $843,000.