History of Clark Air Base 1 History of Clark Air Base

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

On Celestial Wings / Edgar D

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitcomb. Edgar D. On Celestial Wings / Edgar D. Whitcomb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. United States. Army Air Forces-History-World War, 1939-1945. 2. Flight navigators- United States-Biography. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Pacific Area. 4. World War, 1939-1945-Personal narratives, American. I. Title. D790.W415 1996 940.54’4973-dc20 95-43048 CIP ISBN 1-58566-003-5 First Printing November 1995 Second Printing June 1998 Third Printing December 1999 Fourth Printing May 2000 Fifth Printing August 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. Digitize February 2003 from August 2001 Fifth Printing NOTE: Pagination changed. ii This book is dedicated to Charlie Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................................... ii Foreword............................................................................................................................ vi About the author .............................................................................................................. -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

2020 Fall Pulama

FALL 2020 PULAMAThe newsletter for supporters of Hale Makua Health Services Virtual Fundraisers Kupuna Stories New Initiative to Help the Learn about some fun virtual Read a sweet story about the life of Community Needs fundraisers happening on our one of our residents, and how Hale Read how we are partnering up to social media and website. Makua helps bring her family peace help those affected by the impacts of mind. of COVID-19. page 2 pages 5 page 6 TOP STORIES You Helped A Hero’s Journey to Recovery feeling of openness, and enjoyed sitting out in the sun and admiring the birds and plants. “Now, I can practically walk without a cane. Therapy has been wonderful. That’s probably the most positive thing you have going on here.” At her first physical therapy session, therapists started Margaret off slowly, having her stand up by the rails. Even this seemingly simple task was a difficult adjustment for Margaret physically. However, as the week progressed she was gradually able to stand and walk with a Margaret Cabbab is a Registered experience. “I really love it. It’s been very front wheel walker, and by the third week Nurse and one of the heroes working at restful,” Margaret said about her stay. “I she was going up the stairs on her own. Maui Memorial Medical Center who didn’t know how stressed I was, but with “When I came in, there was no way I made sacrifices to care for the community’s the same medication, my blood pressure could walk, stand, rollover in bed, or get up COVID-19 patients. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

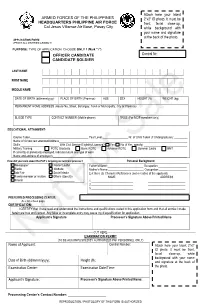

Examination Date/Time: Applicant's Signature

Attach here your latest ARMED FORCES OF THE PHILIPPINES 2”x2” ID photo. It must be HEADQUARTERS PHILIPPINE AIR FORCE front, facial close-up, Col Jesus Villamor Air Base, Pasay City white background with your name and signature at the back of the photo. APPLICATION FORM (PRINT ALL ENTRIES LEGIBLY) PURPOSE: TYPE OF APPLICATION. CHOOSE ONLY 1 (Mark “√”) Control Nr: OFFICER CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SOLDIER LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME DATE OF BIRTH (dd/mmm/yyyy) PLACE OF BIRTH (Province) AGE SEX HEIGHT (ft) WEIGHT (kg) PERMANENT HOME ADDRESS (House No.,Street, Barangay, Town or Municipality, City or Province) BLOOD TYPE CONTACT NUMBER (Mobile phone) TRIBE (For NCIP members only) EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT: Course Taken_______________________________________ Year Level _________________ Nr. of Units Taken (if Undergraduate): _________ Name of School last attended/Address______________________________________________________________________________________ Skill/s__________________________ With Civil Service Eligibility/Licensed? Yes No (if Yes, specify) _____________________________ Military Training: POTC Graduate Basic ROTC Advance ROTC Summer Cadre BMT If currently or previously employed, indicate nature and type of work_______________________________________________________________ Name and address of employer/s__________________________________________________________________________________________ How did you learn about the PAF’s ongoing recruitment process? Personal Background Newspaper Poster/Leaflet Father’s Name:________________________ -

Korea-Taiwan 2019

MEMORANDUM TO: National Officers, National Council of Administration, Department Commanders, Department Senior Vice Commanders, Department Junior Vice Commanders, Department Adjutants, and Past Commanders-in-Chief FROM: B.J. Lawrence, Commander-in-Chief DATE: July 9, 2019 RE: 2019 Trip Report to Guam, Philippines, Taiwan and Korea Overview I departed for the Indo-Pacific on April 12, 2019, to visit U.S. service members, veterans and VFW comrades stationed or residing in Guam, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, as well as our colleagues in the Republic of China on Taiwan. I was accompanied by VFW Director of National Security and Foreign Affairs John Towles. We returned to CONUS April 28, 2019. As a former soldier who spent the majority of my service on the Korean peninsula, I have remained acutely aware of the current geopolitical situation in the region and the impact it has had on everything from the basing of U.S. troops to the continued search for more than 7,700 Americans who remain missing and unaccounted-for from the Korean War and the Cold War. Some 5,300 of our missing are believed to be inside the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. As a result, I felt it was imperative to personally visit some of the primary military installations in the country, to include Camp Humphries, the Joint Security Area, the United Nations Command Korea Headquarters, and to speak directly to service members who are protecting the sovereignty of our allies and U.S. interests. Doing so also allowed me to gain an appreciation for what areas that we as an organization need to focus on in terms of defense spending, quality of life, and readiness issues. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

1 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the WESTERN DISTRICT of TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JOHN A. PATTERSON, Et Al., ) ) Plai

Case 5:17-cv-00467-XR Document 63-3 Filed 04/22/19 Page 1 of 132 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JOHN A. PATTERSON, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 5:17-CV-00467 ) DEFENSE POW/MIA ACCOUNTING ) AGENCY, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) THIRD DECLARATION OF GREGORY J. KUPSKY I, Dr. Gregory J. Kupsky, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746, declare as follows: 1. I am currently a historian in the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s (DPAA) Indo-Pacific Directorate, and have served in that position since January 2017. Among other things, I am responsible for coordinating Directorate manning and case file preparation for Family Update conferences, and I am the lead historian for all research and casework on missing servicemembers from the Philippines. I also conduct archival research in the Washington, D.C. area to support DPAA’s Hawaii-based operations. 2. The statements contained in this declaration are based on my personal knowledge and DPAA records and information made available to me in my official capacity. Qualifications 3. I have been employed by DPAA or one of its predecessor organizations, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), since May 2011. I served as a historian for JPAC from May 2011 to July 2014, and was the research lead for the Philippines, making numerous 1 Case 5:17-cv-00467-XR Document 63-3 Filed 04/22/19 Page 2 of 132 trips to the Philippines to coordinate with government officials, conduct research and witness interviews, and survey possible burial and aircraft crash sites, along with investigations and trips to other countries. -

American Jews Serve in World War II by Seymour "Sy" Brody

American Jews Serve in World War II by Seymour "Sy" Brody When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the United States declared war on Japan and Germany, American Jewish men and women responded to their country's call for the armed forces. Over 550,000 served in the Armed Forces of the United States during World War II. About 11,000 were killed and over 40,000 were wounded. There were two recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor, 157 received the Distinguished Service Medal and Crosses, which included Navy Crosses, and 1,600 were awarded the Silver Star. About 50,242 other decorations, citations and awards were given to Jewish heroes for a total of 52,000 decorations. Jews were 3.3 percent of the total American population but they were 4.23 percent of the Armed Forces. About 60 percent of all Jewish physicians in the United States under 45 years of age were in service uniforms. President Franklin D. Roosevelt praised the fighting abilities and service of Jewish men and women. General Douglas MacArthur in one of his speeches said, "I am proud to join in saluting the memory of fallen American heroes of the Jewish faith." At the 50th National Memorial Service conducted by the Jewish War Veterans of the United States, General A. Vandergrift, Commandant, U.S. Marine Corps, said, "Americans of Jewish faith in the Marine Corps have served with distinction throughout the prosecution of this war. During the past year, many Jewish fighting men in our armed forces have given their lives in the cause of freedom. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

Fy 74 Progress Report on Design Criteria and Methodology for Construction of Low-Rise Buildings to Resist Typhoons and Hurricanes

NBSIR 74-567 FY 74 Progress Report on Design Criteria and IMetliodology for Construction of Low-Rise Buildings to Resist Typhoons and Hurricanes N. J. Raufaste, Jr. and R. D. Marshall Center for Building Technology Institute for Applied Technology National Bureau of Standards Washington, D. C. 20234 July 1,1974 Interim (July 1, 1973 through June 30, 1974) Prepared for The Office of Science and Technology Agency for International Development Department of State Washington, D. C. 20523 Under a Participating Agency Service Agreement (PASA) No. TA(CE) 04-73 NBSIR 74-567 FY 74 PROGRESS REPORT ON DESIGN CRITERIA AND METHODOLOGY FOR CONSTRUCTION OF LOW-RISE BUILDINGS TO RESIST TYPHOONS AND HURRICANES N. J. Raufaste, Jr. and R. D. Marshall Center ^or Building Technology Institute for Applied Technology National Bureau of Standards Washington, D. C. 20234 July 1, 1974 Interim (July 1, 1973 through June 30, 1974) Prepared for The Office of Science and Technology Agency for International Development Department of State Washington, D. C. 20523 Under a Participating Agency Service Agreement (PASA) No. TA(CE) 04-73 M. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Frederick B. Dent, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Richard W. Roberts, Director CONTENTS TABLE OF FIGURES 11 SI CONVERSION FACTORS. ' iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 A. SUMMARY OF PROGRESS FOR FISCAL YEAR 1974 4 ^ Background Information. Wind Research Activities 6 Field Test Sites 6 Research Equipment 11 Wind Tunnel Modeling 14 Collection, Reduction and Analysis of Field Data .... 21 Assessment, Selection and Application of Cllmatological Data 25 International Workshop on Effects of Extreme Winds 25 Library Research 26 Information Transfer to Other Wind Areas 26 Soclo-Economic and Housing Study 27 Philippine Housing Construction Practices 29 B.