PORT of MOSES LAKE Comprehensive Scheme of Harbor Improvements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments to Paine Field Airport; They Have Been Noted

SnohoniLt 1) • 17’ 1 J ,4$~ic~ Comments Countvkitport u amer len ~F Environtuental Assessinen~ ~~S4LW, LOft. 9~t7f NSCtEwJ cn~, cc~c i2~k ~u u~ COMMENTS: A~ 4o~i-c ~M ~—Tw*~ C Ia Dave Waggoner Cayla Morgan Director Environmental Protection Spedalist Snohomish County Airport Seattle Airports District Office Comments to 3220 100th Street Southwest or Federal Aviation Administration Everett, Washington 98204 1601 Lind Avenue, SW Barnard Dunkelberg >? Company Email. [email protected] Renton, Washington 98057-3356 BridgeNet International Email. [email protected] Synergy Consultants Gibson Traffic Consultants Thank You! D.1 Response to Comment Dear Jeanne and George Dalton: Thank you for your comments to Paine Field Airport; they have been noted. D.2 -Original Message— From: [email protected] [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Wednesday, January 20, 2010 5:40 PM To: Waggoner, Dave; Dolan, Bill; Ryk Dunkelberg; Ryan Hayes Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]; Roland. J.McKee@faa . gov Subject: Fw: Paine Field review Cayla Morgan Environmental Protection Specialist Seattle Airports District Office Federal Aviation Administration 425—227—2653 Forwarded by Cayla Morgan/ANM/FAA on 01/20/2010 04:38 PM I > From: I I > I > IStephen Dana <[email protected]> > > I To: I > I > Cayla Morgan/ANM/FAA@FAA I > > Date: I > > 101/20/2010 03:22 PM > > Subject: I > > IPaine Field review > D.3 January 19, 2010 Cayla Morgan Environmental Protection Specialist Seattle Airport District Office, FAA 1601 Lind Ave SW Renton, WA 98057 Ms. Morgan, The matter of commercial air service at Paine field is up for environmental review before your office in the coming weeks. -

NOVEMBER 3, 1980 I WASHINGTON, D.C

THE whl7”c hci;Sg 1 TiiE OAiLY DIARY OF PREStDENt JIMMY CARSER 1 SF--.- ! Loc.xrIoN 3AsE &to.. Day. Yt.1 me. f THE WHITE HOUSE NOVEMBER 3, 1980 i WASHINGTON, D.C. TIX E DAY . -*: L 5:00 a.m. MONDAY I R I The President received a wake up call from the White House f signal board operator. I 5:18 i R The President talked on a conference line with: , I Edmund S. Muskie, Secretary of State I warren M. Christopher, Deputy Secretary of State 5 :*20 597 P‘ The President talked with his Press Secretary, Joseph L. "Jody" iI Powell. 5 = 31 5 = 35 P The President talked with Hamilton Jordan, Deputy Campaign Chairman, Carter Mondale Presidential Committee, Inc. 5:50 f The President went to the Oval Office. 5:50 5:51 P The President talked with Charles H. Kirbo, partner with King I t and Spalding law firm, Atlanta, Georgia. i 6~26 ; P The President telephoned the First Lady. The call was not I I completed. I I I 7:02 / 7:Og R 1 The President talked with the First Lady. I ; The President met with: 8:oo 1 8:18 Mr. Powell 8:oo 1 8:18 Gerald M. Rafshoon, President, Rafshoon Communications, ! I I I Washington, D.C. 8:oo 1 8:18 Patrick J. Caddell, President, Cambridge Survey, I I Cambridge, Massachusetts Mr. Kirbo Jack H. Watson, Jr., Chief of Staff Mr. Jordan a:18 The President went to the Cabinet Room. He was accompanied by: Mr. Watson Mr. -

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

Informational Handout: King County International Airport-Boeing Field Seattle, Washington

Informational Handout: King County International Airport-Boeing Field Seattle, Washington Published Visual Flight Rules (VFR) routes for arrivals and departures. Project Background The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) cancelled two existing VFR routes for aircraft landing and departing King County International Airport-Boeing Field (KBFI) and replaced them with newly defined routes (retaining some of the existing names). The term “routes” can best be described in this instance as a “set of pre-coordinated instructions” that is given to VFR pilots. The routes enhance safety by increasing separation between arrival and departure flows into KBFI, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (KSEA), and Renton Municipal Airport (KRNT). Purpose of Changes There have been Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) events involving VFR aircraft arriving and departing KBFI, and these routes are intended to reduce TCAS events and enhance safety. TCAS monitors the airspace around an aircraft for other aircraft equipped with proper equipment, independent of air traffic control, and warns pilots of the presence of other properly equipped aircraft in the immediate area. Project Description The project results in a change to past operating procedures by publishing several existing routes for VFR aircraft to use when arriving and departing from either runway configuration at KBFI. KBFI Airport Traffic Control Tower (BFI ATCT) now has the ability to assign published routes rather than issuing tailored instructions. The new VFR routes provide better predictability, enhance safety, and improve the segregation of aircraft arriving and departing KBFI. What Changed The new VFR routes follow pre-existing air traffic flight tracks that are assigned by BFI ATCT and no new areas will experience new air traffic overflights. -

Starbucks Hangar Facility OFFERING

Starbucks Hangar Facility OFFERING 6771 PERIMETER ROAD S, SEATTLE WASHINGTON 98108 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On behalf of Starbucks Corporation, Kinzer Real Estate (“KRES”) has been retained to present to qualified parties the opportunity to purchase its leasehold interest (the “Offering”) in its current corporate hangar facility at King County International Airport (“KCIA”). Due to its increased international business and corresponding increase in travel requirements, Starbucks required an expansion of its fleet and hangar facility that its current hangar site could not accommodate. In November 2011, Starbucks secured a new lease with King County at a parcel that will accommodate its future aviation requirements, and as a result is looking to dispose of its current hangar upon completion of its new hangar. The Offering provides the rare opportunity to secure long-term access to an existing, operational hangar facility at KCIA at a favorable economic cost to potential alternatives. The Offering consists of Starbucks’ leasehold interest in an aviation hangar facility located at 6771-A Perimeter Road at KCIA. The facility consists of 14,154 square feet of improvements upon 44,252 square feet of land owned by King County. The interest is secured via sublease with Master Lessee King County Jet Center (“KCJC”), which leases the land directly from KCIA. Starbucks’ lease term is coterminous with KCJC’s lease term. Starbucks’ sublease provides for extensions coterminous with extensions of the Master Lease. Although the Master Lease does not provide KCJC with specific renewal rights, KCIA customarily renews ground leases with responsible ground lessees that professionally maintain and operate existing hangar facilities. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study Next Steps

Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study Next Steps DAVID FLECKENSTEIN, AVIATION DIRECTOR Washington State Transportation Commission Meeting March 16, 2021 Planning for the Next Aviation Revolution • Electric aircraft are flying today and new companies are entering the market every day – Approximately 215 models under development • WSDOT completed a one year consultant led study on the potential impacts of electric aircraft for Washington State in November 2020 • This technology has the potential to open up new markets for air travel while reducing greenhouse gas emissions • Planning for implementation of electric aviation is key to successful adoption 2 Electric Aviation in Washington Washington State could become the epicenter for electric aircraft • Development • magniX, headquartered in Redmond, is developing the next generation of aircraft propulsion with its electric engines • Testing • AeroTEC is currently flight testing a Cessna Caravan converted to electric propulsion with a magniX engine at Grant County International Airport in Moses Lake • Manufacturing • Recently announced that Eviation plans to assemble the Alice at Arlington Municipal Airport o Alice utilizes the magniX engines 3 Washington Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study - Study Areas of Emphasis • Identification of current and projected airport infrastructure improvement needs to accommodate electric aircraft • Evaluation of projected economic impact resulting from increased access to air transportation • Demand forecasting for electric propulsion regional passenger air -

PAINE FIELD HANGAR UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST Everett, Washington 98024

FOR SALE PAINE FIELD HANGAR UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST Everett, Washington 98024 CONTACT US KATRIN GIST CBRE, Inc. Associate 10885 NE 4th Street +1 206 947 1399 Suite 500 [email protected] Bellevue, Washington 98004 www.cbre.com/bellevue FOR SALE PAINE FIELD HANGAR HANGAR FEATURES PRICE: $680,000 This 5,625 sq. ft. aircraft hangar is an attractive option for those looking for an alternative to Boeing Field. Recently built in 2007, the hangar still feels new and offers a comfortable build-out that could be used for a variety of aviation purposes. Serving as a general aviation, industrial and commercial airport for the North Puget Sound region only 29 minutes north of Seattle, Paine Field provides a wide variety of aviation and industrial facilities, services and activities. It is ideal for the Northwest aircraft owner/operator. + 75 ft. x 75 ft. + 22 ft. clear height + 75 ft. wide hydroswing door + Radiant heat + Insulated + High bay halogen lighting + Sprinkler fire suppression system + Electrical system including 100 amps: − 110 and 220V + Security card gate access + Includes 350 sq. ft. office, bathroom and shower + Ground lease through May 31, 2041 with 15 year extension option UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST Everett, Washington 98024 BUILDING D SITE PLAN BUILDING D FLOOR PLAN UNIT D103 Not to scale FOR SALE UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST PAINE FIELD HANGAR Everett, Washington 98024 AERIAL MAP 9800 29th AVENUE WEST UNIT D103 © 2015 CBRE, Inc. The information contained in this document has been obtained from sources believed reliable. While CBRE, Inc. -

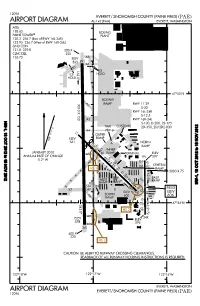

Airport Diagram Airport Diagram

12096 EVERETT/ SNOHOMISH COUNTY (PAINE FIELD) (PAE) AIRPORT DIAGRAM AL-142 (FAA) EVERETT, WASHINGTON ATIS 128.65 BOEING PAINE TOWER PLANT 120.2 256.7 (East of RWY 16L-34R) 132.95 256.7 (West of RWY 16R-34L) GND CON 121.8 339.8 200 X CLNC DEL 220 126.75 AA ELEV 16R 563 A1 K1 162.0^ ILS ILS HOLD HOLD A 47^55'N BOEING 9010 X 150 A2 RAMP RWY 11-29 S-30 RWY 16L-34R S-12.5 A3 RWY 16R-34L NW-1, 18 OCT 2012 to 15 NOV S-100, D-200, 2S-175 TWR CUSTOMS 2D-350, 2D/2D2-830 11 A4 787 B .A OUTER ELEV RAMP VAR 17.1^ E 561 NORTH 117.0^ C RAMP INNER C1 JANUARY 2010 D1 RAMP TERMINAL ELEV A5 16L D-3 ANNUAL RATE OF CHANGE D-3 4514 X 75 C 597 0.2^ W X G1 F1 A6 X D2 CENTRAL X G2 F2 HS 1 RAMP X D3 162.5^ X H D 3000 X 75 A X X X D40.9% UP G3 EAST WEST X X RAMP RAMP W3 X NW-1, 18 OCT 2012 to 15 NOV FIRE F X STATION 297.0^ D5 FIELD K7 A7 E G4 ELEV F4 ELEV A8 SOUTH 29 600 606 RAMP G 342.5^ 47^54'N 342.0^ G5 A G6 HS 2 F6 A9 A 34R ELEV ELEV 578 596 A10 34L 400 X 220 HS 3 CAUTION: BE ALERT TO RUNWAY CROSSING CLEARANCES. READBACK OF ALL RUNWAY HOLDING INSTRUCTIONS IS REQUIRED. -

Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Status Report September 2008 Through June 2009

Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Status Report September 2008 through June 2009 August 2009 Publication No. 09-09-183 Printed on recycled paper This report is available on the Department of Ecology home page on the World Wide Web at http://www.ecy.wa.gov/programs/tcp/sites/lower_duwamish/source_control/sc.html For a printed copy of this report, contact: Department of Ecology Toxics Cleanup Program Phone: 360-407-7170 Refer to Publication Number 09-09-183 If you need this publication in an alternate format, please call the Toxics Cleanup Program at 360-407-7170. Persons with hearing loss can call 711 for Washington Relay Service. Persons with a speech disability can call 877-833-6341. Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Status Report September 2008 through June 2009 Produced by Dan Cargill Toxics Cleanup Program Northwest Regional Office Washington State Department of Ecology Bellevue, Washington and Science Applications International Corporation 18912 North Creek Parkway, Suite 101 Bothell, WA 98011 With Assistance from: City of Seattle King County Port of Seattle U.S. Environmental Protection Agency August 2009 Waterbody No. WA-09-1010 Publication No. 09-09-183 This page intentionally left blank. LDW Source Control Status Report Table of Contents Page Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... xi List of Acronyms..................................................................................................................... xxvii -

THE RISE of CARGO-FOCUSED HUB AIRPORTS PANDEMIC YEAR 2020 Chaddick Policy Brief | March 25, 2021 by Joseph P

THE RISE OF CARGO-FOCUSED HUB AIRPORTS PANDEMIC YEAR 2020 Chaddick Policy Brief | March 25, 2021 By Joseph P. Schwieterman and Euan Hague Our analysis of newly released air cargo traffic data for 2020 shows that: Tonnage at cargo-focused hub airports, i.e., airports with extensive cargo traffic but little or no passenger traffic, grew 31.4% from 2019 to 2020 Chicago Rockford, Wilmington Air Park, Ft. Worth Alliance, and Boeing Field/King Co. airports were among the leaders of the 14 cargo-focused hubs identified A surge in online buying for at-home delivery is fueling much of the growth Airports that are focal points for air freight integrators DHL, FedEx, and UPS and have more passenger traffic than cargo-focused hubs grew more slowly, yet at a still substantial 9.0% rate The rapid growth raises important social, economic, and environmental questions he emergence, evolution, and performance of specialized cargo airports have long been of T interest to investors and policymakers in the United States.1 This Chaddick Policy Brief reviews the recent growth of cargo-focused hub airports, i.e., airports that have significant roles in cargo movement while handling a low volume of passenger traffic. Examples of such airports are California’s Sacramento Mather and Ft. Worth Alliance airports. This Brief reviews findings from our analysis of newly released 2020 data and offers brief case studies of six prominent cargo-focused hub airports. CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY CONTACT: JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, PH.D. | PHONE: 312.362.5732 | EMAIL: [email protected] PHOTO CREDIT (ABOVE): A UPS MD 11 AT SAN BERNARDINO INT’L, JAN. -

National Transportation Safety Board Aviation Accident Final Report

National Transportation Safety Board Aviation Accident Final Report Location: Spokane, WA Accident Number: SEA04FA023 Date & Time: 11/29/2003, 0801 PST Registration: N439AF Aircraft: Fairchild Swearingen SA227-AT Aircraft Damage: Destroyed Defining Event: Injuries: 1 Fatal Flight Conducted Under: Part 135: Air Taxi & Commuter - Non-scheduled Analysis The pilot, who had more than 3,340 hours of pilot-in-command time in the make/model of the accident aircraft, and was very familiar with the destination airport and its ILS approach procedure, departed on a cargo flight in the SA227 turboprop aircraft. The aircraft was dispatched with the primary (NAV 1) ILS receiver having been deferred (out of service) due to unreliable performance the evening before the accident, thus leaving the aircraft with the secondary (NAV 2) ILS receiver for ILS use. The pilot arrived in the destination terminal area and was given vectors to intercept the ILS localizer, and radar data showed the aircraft intercepting and tracking the localizer accurately throughout the approach. Mode C altitude readouts showed the aircraft approaching from below the glideslope at the required intercept altitude of 4,100 feet, passing through and above the glideslope and then initiating a relatively constant descent, the angle of which exceeded the glideslope angle of -3.5 degrees. Weather at the destination airport was 400 foot overcast and the decision height for the ILS/DME runway 21R approach was 270 feet. The aircraft passed through the tops of trees in level flight about 530 feet above the airport elevation and slightly under 3 nautical miles from the runway threshold.